-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Regent Journal of Business and Technology

2024; 1(1): 1-30

doi:10.5923/j.ribt.20240101.01

Received: Dec. 26, 2023; Accepted: Jan. 12, 2024; Published: Jan. 15, 2024

An Investigation into the Utilization and Integration of Digital Payments Schemes Using ISO 8583 Standard to Promote Cashless Payments in Zambia

David Kabulubulu Chanda , Simon Tembo

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Zambia

Correspondence to: David Kabulubulu Chanda , Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Despite strides in payments technology, use of cash in consumer payments was prevalent in Zambia. In addition to other factors, the main factor for this low adoption of digital payments was lack of integrated payment schemes. In attempt to bridge this identified gap, the aim of this research was to find means of utilizing digital payments in consumer payments by trying to define an integration model for payment schemes using ISO 8583 standard. ISO 8583, 1993 was chosen to leverage on existing infrastructure available for all payments schemes to use at the Zambia Electronic Clearing House. The model would include technical and operational aspects that would facilitate use of digital payments by the three major take holders, being payment companies, merchants and consumers. Three baseline studies were conducted on each category of stakeholder using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Inferences from the studies were used in formulating an integration model by defining both technical and operational integration aspects. Technical definition involved redefinition of message flows, data fields and data fields population rules for the ISO 8583 MTI messages. The model was tested and validated by developing prototype acquirer and issuer interfaces that processed ISO 8583 messages, and neaPay ISO8583 processing simulator switch from neaPay Payment Solutions, representing the interconnecting switch at NFS. The developed model demonstrated that introduction of a central integration point would stimulate cashless payments, as it created an ecosystem which could address all stakeholder pertinent issues preventing utilization, such as security, cost and profitability.

Keywords: Digital payment scheme integration, ISO 8583 customization, NFS E-Money, Cashless payments

Cite this paper: David Kabulubulu Chanda , Simon Tembo , An Investigation into the Utilization and Integration of Digital Payments Schemes Using ISO 8583 Standard to Promote Cashless Payments in Zambia, Regent Journal of Business and Technology, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2024, pp. 1-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ribt.20240101.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

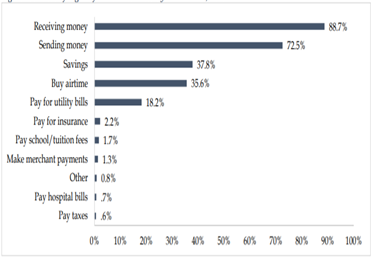

- Digital payments involve the electronic transfer of cash from one party to another using a payment platform such as mobile banking, Internet banking or credit/debit card [8]. The platforms are facilitated by a payments company or scheme such as VISA, MasterCard, Zambia National Financial Switch, Commercial Banks, FinTechs, MNOs and the like.The research investigated the current utilization of existing digital payments schemes in Zambia to make consumer payments as well as the how several existing closed loop digital payment schemes may be integrated using ISO 8583 standard by leveraging on existing infrastructure that already supported the ISO 8583stadard at the Zambia Electronic Clearing House Limited (ZECHL) under the National Financial Switch (NFS).The years leading to 2022 had witnessed dramatic changes in the payments industry with the rise in digital payments worldwide. These changes are accelerating as more people around the world use contactless cards and smartphones to pay each day transforming the face of commerce as not just every person, but every device that a person interacts with, becomes a commerce opportunity [1] [2] [3]. Zambia has not been left out in this rise in digital payments innovations which has recently been further fuelled by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.However, despite this rise in electronic payment solutions, the use of cash in consumer payments is still dominant [2]. According to a research by ZICTA, in Zambia, only 25.4% of total population had access to mobile telephones in 2014, this number rose to 53% in 2018. This increase in access to mobile phones reflects the increase in digital payments as most of digital payments are performed through mobile telephones. However, as depicted in Figure 1.., this increase is mainly around peer to peer transfers as opposed to consumer payments. By deduction, this means that most of consumer payments in Zambia were performed by cash [6].

| Figure 1. Usage of Financial Services by individuals |

| Figure 2. Closed loop payment schemes depiction |

2. Literature Review

2.1. Generic Digital Payments Ecosystem in Zambia

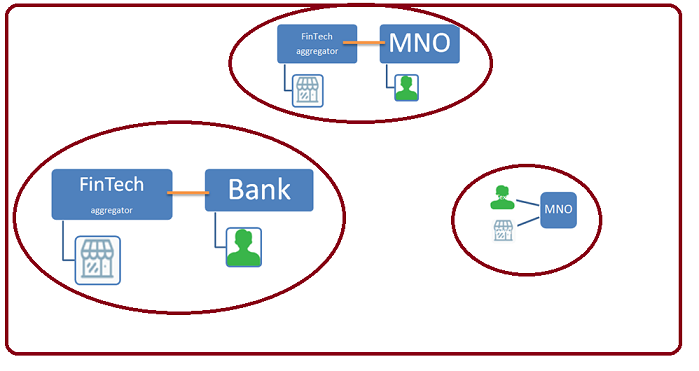

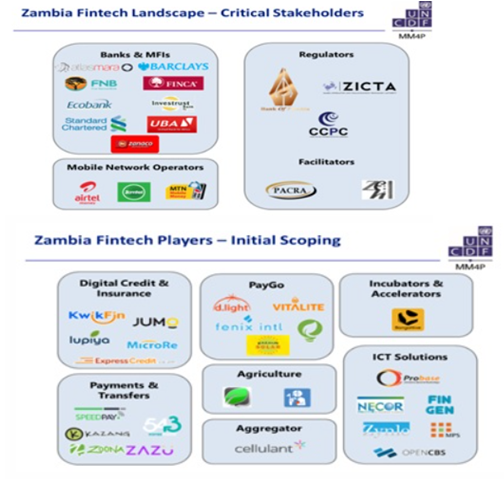

- According to UNCDF and Bank of Zambia [7] [19], Zambia’s payment landscape may be grouped into two categories, the critical stakeholders that form the backbone of payments in Zambia, and the mushrooming FinTechs playing a pivotal role in innovation but who’s success depends on how they partner with the critical stake holders. Fig 2-4 shows some examples of the two categories.

| Figure 3. Fintech Landscape in Zambia |

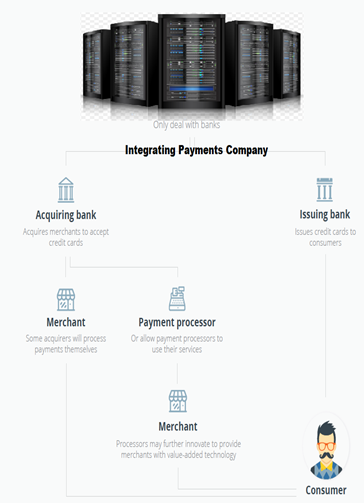

2.1.1. Digital Payments Model (Debit Card Based)

- When it comes to consumer payments, the foregoing stakeholders facilitate payments using models that generally interconnects a seller and a buyer. Several models exist that depict the payments ecosystem by categorizing the stake holders by the roles they play in the ecosystem. One common model derived from the debit/credit card payments systems as in figure 4 is commonly used. The model categorizes the core players in the payment transaction. Each payment transaction has a Payer and a Payee, where the payer has to transfer funds digitally to the Payee. This transfer of funds is facilitated by a payments company that connects the payer’s platform to the payee’s platform. For the ultimate settlement or transfer of funds, there is at minimum a bank to facilitate the actual movement of funds from the Payer’s bank to the Payees bank. Figure 4 shows how the different players sit in the payments model. The model is applicable to any digital payments scheme, even away from debit/credit card schemes [8] [20] [21].

| Figure 4. The Debit Cards payments model |

2.2. Integration of Payment Schemes and the N-Squared Scalability Problem

- In Zambia, there are several payments companies most of which are operating as closed loop systems, i.e. not interconnected to each other. Based on the premise that the more the integrations the higher the adoption of digital payments, each payment scheme may have to have interconnection with a significant number of other payment schemes. This however, introduces the N-squared problem. This means that for absolute interconnections, the number of interconnections would grow on the order of N-squared, with N being number of payment schemes in this case. A single interconnection point solves this problem.

2.2.1. Application Programing Interfaces (APIs)

- Integrations involve the interconnection of different payment scheme software via API’s or ISO standards. The APIs may be SOAP of RESTful. Many digital payment solutions have adopted RESTful web services as they are lightweight, flexible and efficient. Integrations are also achieved via several ISO defined interconnection standards such as ISO 20022 and ISO 8583. ISO 20022 is the newer version and has superiority functions over the order ISO8583. However, In Zambia, ISO 8583 enjoys widespread use and available infrastructure at ZECHL under the NFS. However, the standard would need customization of the data fields and message flow to meet the non-card based usage in consumer payments [12] [13].ISO 8583 is a standard for systems that exchange electronic transactions made by cardholders using payment plastic cards. An ISO 8583 message is made of Message type indicator (MTI), One or more bitmaps, indicating which data elements are present and the actual data elements, the fields of the message as in figure 4 [14] [17] [18].

| Figure 5. ISO8583 Message Structure |

2.3. Factors in Payments Systems Integration

- In addition to the N-squared problem, empirical research has revealed several reasons as to why payment schemes may be having operating in silo as detailed below;

2.3.1. Standards, Models and Architectures

- Different payments systems are developed using different standards, models and architectures, this presents a challenge when two systems of different architectures try to interconnect. For the systems to connect, an integrating model would have to be developed which should encompass all aspects of integration including what standard to follow (API or ISO), model for systems interconnection, allocation of tasks and responsibilities, architectures, how settlements would be done, pricing models, dispute resolution and ultimately conformity to regulation. [23].

2.3.2. Security

- Security is a major factor in any integration that would be there, it may be a determining factor as to whether a payment system is willing to interconnect to another. For example, for participants in the debit card industry, any new entrant will have to undergo Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCIDSS) certification before they are allowed onto the network. Payment systems like Visa and Mastercard will not accept any new entrant without a PCDISS certification. Regulators find it hard to balance between rapid acceptance of new technologies on the market and making sure that each one of those players is compliant to the best security practices. Stringent security requirements may hinder small but innovative players [22] [24].

2.3.3. Profitability

- Integration in many case comes with costs, any institution looking to integrate with another will definitely consider the profitability of the venture. The benefits may be the direct income charged to the users of the system or inform of intangible benefit that may lie in the users’ experience. A system that is interconnected is generally widely used and hence perceived to be reliable and established, this good reputation does profit the payments company in many ways.

2.3.4 Regulation

- Regulation is always at the centre of any financial system. Most governments foster financial inclusion by regulating how the financial industry works. For example, in Zambia, the government through BOZ and Zambia Electronic Clearing house introduced the National Financial Switch (NFS) and directed all banks to route all local debit card transactions through this switch [5] [7] [25].

2.4. Utilization by Merchants and Consumers

- Research on utilization of payment technologies, sometimes referred to as diffusion or acceptance of innovation, has been based on several common theories which include Diffusion of Innovation theory, Theories of Reasoned Action and Theories of planned Behaviour (TRA/TPB), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). The theories speak to either the rate at which innovation is utilized [10]. or the underlying behavioural intentions to use or not use technology [10] [11]. Empirically, According to a research by GSMA [26], there is an increase in smartphone adoption in emerging markets and a growing internet penetration that is fuelling the expansion of e-commerce. E-commerce has become a significant tool in unlocking job creation and innovation for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in developing countries. Further, the World Bank’s Global Findex database shows that in key mobile money markets, e-commerce is being used by low-income and rural people. However, in these markets, over 70% of e-commerce payments involve cash-on-delivery payment processes, which are expensive, inefficient and time-consuming for both merchants and buyers [26] [27]. Several scholars’ research using the above mentioned theories, have attributed the low uptake of digital payments around consumer payments to several factors as below.

2.4.1. Poor Digital Payment User Experience Results in High Drop-Offs

- GSMA [9], discovered that users are often instructed to follow 8-10 step processes independently, and are forced to enter numerous details (merchant numbers, reference codes, amounts) precisely, creating multiple chances for error. In addition, drop-off points were also due to network failure, lags in sending the messages and expiration of the One Time Passwords (OTP). The factors extend to other forms of digital payments, for example according to a survey by visa [1], most debit card users found the checkout time lengthy, and a high network failure for most POS transactions in Zambia. These users tend to lose trust in the payment scheme and are more likely to carry cash as a backup or entirely doing away with the debit card payments all together. Poor user experience is not only limited to the payment aspect of the integration—the delivery and refund / exchange processes are also at the core of the online purchasing experience. Delivery in most emerging countries is typically slow and inefficient because of the poor address system in cities and lack of widespread reliable delivery services in non-urban areas for the case on online purchases were the customer buys in a non-brick and motor shop a expects the shop to deliver the product later. The refund / exchange process is also complex and lengthy, with customers often only being able to receive vouchers in place of a faulty or non-desired item.

2.4.2. Lack of Integration of Payment Schemes

- According to the FinScope Zambia, 2015 research demographics [4], financial inclusion was over 50%. The study also showed that over 54.8% of Zambian adults live in rural areas. When we look at most integrated payment scheme in Zambia, the debit card network, it has very minimal rural penetration. Banks who are the primary provider of this service incur huge expenses in running ATM cash points in rural areas. This means the over 54.8% of financially included adults are accessing financial services via alternative payment schemes which are mostly closed loop. If a consumer and merchant are on two different payment scheme, the transaction cannot happen [5] [7].

2.4.3. Security

- According to a study by Visa [1] on fraud, it showed that most customers that had experienced fraud directly or through a close relation tend to show less confidence in the digital payments schemes. Customers feel the systems are not secure enough and would rather carry cash for their consumer payments and/or peer to peer transfers. On the side of merchants, the merchant has a risk of paying for fraudulent transactions [5].

2.4.4. Cost

- According to Ann Kjos [28], most merchants prefer cash because they feel accepting debit cards is expensive. In the debit card model, the merchants is charged for accepting a digital payment, the rationale is that the merchant saves in terms on handling cash and has instant or almost instant access to the money in their account and are able to utilize it quicker that if they had received cash which they had to first deposit into a bank account. Other than paying for accepting the terminal, the merchant is also charged for using the POS terminal, the merchant is also liable to fraudulent transactions.

2.4.5. Awareness

- In a study by P. Ratan [8] on digital trends issues and opportunities, it was discovered that some consumers use cash simply because they are not aware that they can make a digital payment. This is a trend noticed even in a population that is fairly informed and savvy. Like in the case of the bank customers that had withdrawn 22 billion kwacha on the ATM in 2019, a good number might have not known that they were able to make payments with their card at various shops [5] [7].

2.4.6. Regulation and Policy

- Regulation plays a pivotal role in the payments industry. Establishment and implementation of policy that promote digital payments can help increase the number of digital payments in country [5]. There are seral ways in which the government can stimulate digital payments including making cost of digital payments cheaper by reducing tax on digital payments technology such as ATMs, POS, software procurements, reduction of physical cash in circulation and fostering awareness and training to the general populace [25].

3. Methodology

3.1. Introduction

- The generic methodology for the research was mixed methods research in which both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from three baseline studies.

3.2. Base Line Studies

- Literature review exposed three main stakeholders in digital payment system integration and utilization namely the payment companies that facilitate the payments, the merchants that sale the goods or services and the consumers that buy the goods or services. To help in the development of the integrations model, baseline studies were conducted on each of the three categories to draw the much needed insights in the development of the integration model.

3.3. Payment Companies: Challenges Faced by Digital Payment Companies in Integration

3.3.1. Sampling

- For this baseline study, purposive sampling was used to identify payment companies that facilitate digital payments. Homogenous purposive sampling was chosen because the researcher’s focus was on particular characteristics of the population that were of interest to enable the researcher answer the research questions which were related to digital payments integration by the digital payment companies. Five digital payments service providers namely, Zambia Electronic Clearing House ZECHL, Indo Zambia Bank, Cgrate Zambia, Cellulant Zambia and Airtel Zambia were engaged in interviews, observation and collection of digital payments statistics. The institutions had been chosen to have representation from different types of digital payments service providers covered. ZECHL as pivotal as the integrating company that run a switch that’s supports ISO 8583 integrations under the NFS.

3.3.2. Data Collection

- For the purpose of determining the challenges faced by digital payments schemes in integration and understanding the current business processes in consumer digital payments; review of literature, interviews, and payments company observation were used. Review of literature helped the researcher frame purposive questions for interviews conducted with the digital payments companies. Interviews helped the researcher close gaps that would have been left out during the literature review process. Observation and study of the sampled stakeholders enriched understanding of the challenges faced by the payments companies. From the findings in purposive literature review, interview, observations and study of the digital payments companies, a digital payments integration model was designed, validated and critiqued. Tools used for the design and validation included neaPay payment solutions Issuer and Acquirer simulator and switch which supports ISO 8583 messages. A prototype interface which was able to pack messages to and unpack and parse messages from the neaPay ISO8583 simulator, was developed using PHP server side scripting language.

3.4. Adoption of Digital Payments by Sellers (Merchants) and Buyers (Consumers) Payments

3.4.1. Sampling

- Merchants that accepted both cash and digital payment means were purposively sampled, similarly, consumers that had options of paying by cash or digitally were also purposively sampled. The population size for the number of merchants was established from BOZ report on digital payments [5] [7]. The report indicated that there were over 6,915 merchants accepting digital payment forms. The population size for number of consumers was established using the demographic findings of FinScope Zambia, a research conducted by Financial Services Deepening Zambia (FSD Zambia) on financial inclusion [4]. The research indicated that over 8.9 million Zambians were financially included and were able to make consumer payments. According to the World Bankv [32], Zambia’s urban population by 2021 was 45% of total population.However, homogenous purposive sampling was chosen for both categories of participants because the researcher’s focus was to build on already established reasons for non-adoption from review of similar research to be used as insights in development of the integrating model using ISO 85833. The conveniently sampled participants were 50 merchants and 170 consumers.

3.4.2. Data Collection

- Two sets of self-administered questionnaires were sent to the purposively sampled merchants and consumers via google docs forms. The contents of the questionnaires were guided by the findings in the literature review. Several adoption of technology theories were reviewed and their finding used to frame both closed ended and open ended questions to help in the development of a model that encourage the merchants to accept payments digitally as opposed to cash. The theoretical literature had indicated that the key independent variables that affect digital payments utilization are user experience, lack of integration, security, cost, awareness and regulation and policy. And hence the questionnaires tried to validate if this was a true reflection from Zambia’s merchants and consumers.

3.4.3. Presentation

- Descriptive statistical analysis technique was used to analyse the data obtained from the merchant’s questionnaire. Qualitative data were analysed by patterns and trends that were categorized and interpreted in relation to how it influences the design of the integration model. These responses were grouped according to themes of the questions. Furthermore, quantitative data were analysed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics were applied to the processed data by showing variable frequency distributions from the responses obtained. Data were presented using graphs, charts, tables and percentages.

4. Results and Discussions

- The aim of this research was find means of utilizing digital payments in consumer payments by trying to define an integration model for payment schemes using ISO 8583 standard. Three baseline studies were conducted.

4.1. Payment Companies: Challenges Faced by Digital Payment Companies in Integration

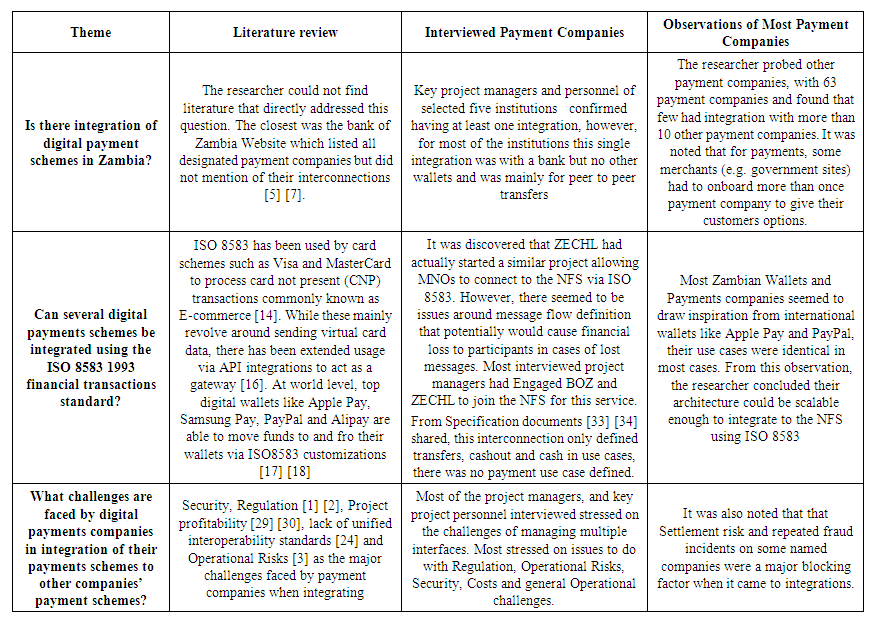

- The objectives of this baseline study were to firstly find out if there were integration or interconnection of different payment networks in Zambia for consumer payments, secondly, to find out if ISO 8583 1993 standard could be used to interconnect several payment companies and finally to find out what challenges if any, are faced by the payment companies in integration process. The study implored qualitative method where five payment companies were interviewed, 63 BOZ designated payment companies observed and literature reviewed. The results are summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1. Payment Company Integration Summary Results |

4.1.1. Summary

- This base line study answered the survey questions. There was little integration of payment companies in Zambia, ISO 8583 can be used to bring about integrations and there were challenges around integration that needed to be considered for any defined integration model. These findings were used in the customization of the ISO 8583.

4.2. Adoption of digital Payments by Sellers (Merchants) and Buyers (Consumers) Payments

- The main goal of these two baseline studies were to find out why there was little adoption of digital payments by the merchants and consumers despite them currently having options to utilize the same.

4.2.1. Why do Merchants Accept Cash Payments in Zambia

- Several surveys around technology acceptance models indicated that the intention to use or not use a payment technology where based on perceptions such as cost, convenience and past experience [11]. The merchants were given canned responses based on these suggestions from literature review. It however turned out that the major factor, accounting for 31% of responses was the willingness of the consumers to pay electronically. Other factors still remains relatively prevalent such as perceptions on cost, and generally how the merchant’s payment operations are handled by their payment network. One notable deviation from what literature had suggested in [11] was that payments companies were not aware of electronic payments or that it was difficult to work with such payments. The results indicated otherwise. However, the latter may also be the concentration risk of homogenous sampling as Hutchinson [31] puts it where the sample responses may not represent the entire population.

4.2.2. Reasons for Cash Payments by Consumers

- Cash payments are predominant, from results of this baseline study the major reason was that it was the only option given by the merchant. This is supported by the fact that there was less integration, hence most merchants, especially the small business, would prefer receiving cash as it is expected that most consumers would be able to pay by cash. The issue of cost was also a major factor, consumers are charged when paying cashless and this results in most preferring cash. Contrary to the literature, the results showed that awareness was not a major problem, this can be backed up by the fact that recent years have seen many digital payment options being developed and advertised by established companies such as Visa and MasterCard [1] [2].

4.2.3. Summary

- The two baseline studies gave some valuable insights as to why merchants and consumers prefer cash as opposed to electronic payments. The reasons suggested by literature review where to some extent affecting merchants and consumers’ decision in utilization of digital payments, however, slight deviations were noticed, for example, awareness was not really a factor as suggested by literature review. The insights were incorporated in the operational aspects if the developed model. These operational aspects speak to cost for consumers and merchants, how quickly merchants account get credited and dispute resolution timeframes.

4.3. Development of the Digital Payments Integrations Model

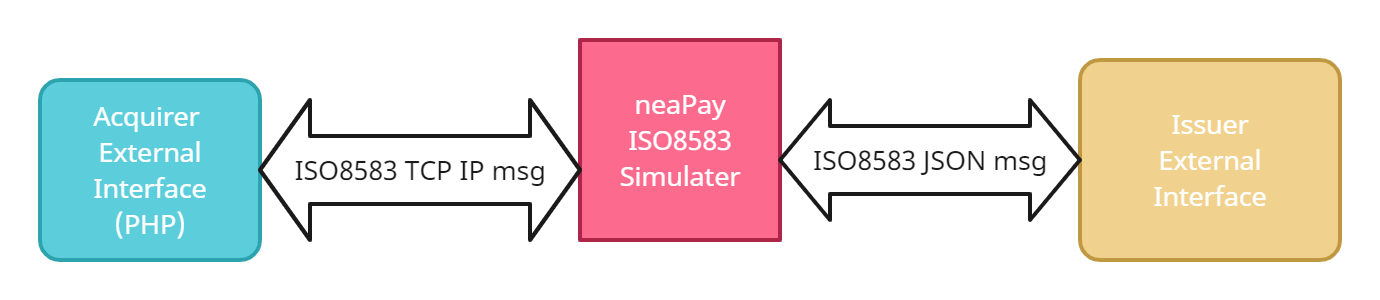

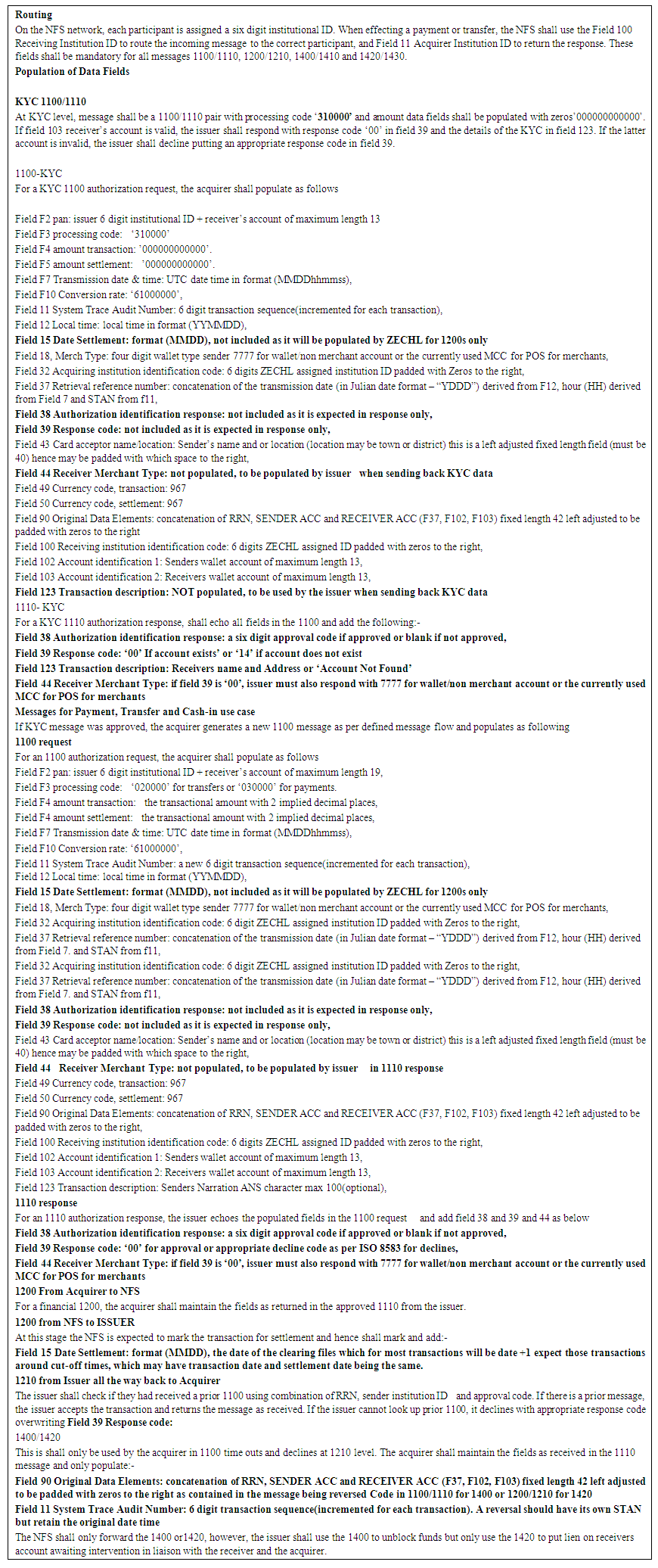

- The inferences drawn from the three baseline studies were used to develop the integration model. It was observed that Zambia had a National Financial Switch (NFS) at the Zambia Electronic Clearing House (ZECHL) that was supporting debit card payments, but could be leveraged on to support non card originated transactions by modifying the Data Fields and the Message flow of the ISO 8583 message standard. This led to the definition of the payment use cases to be supported, then redefining the necessary data fields of the ISO 8583 message to support the use cases then finally defining message flow to carter for network failures and lost messages. A prototype interface was developed using PHP, the interface was able to pack an ISO 8585 message and transmit it to the neaPay switch, which sent back a response to be unpacked and parsed by the proto type interface.

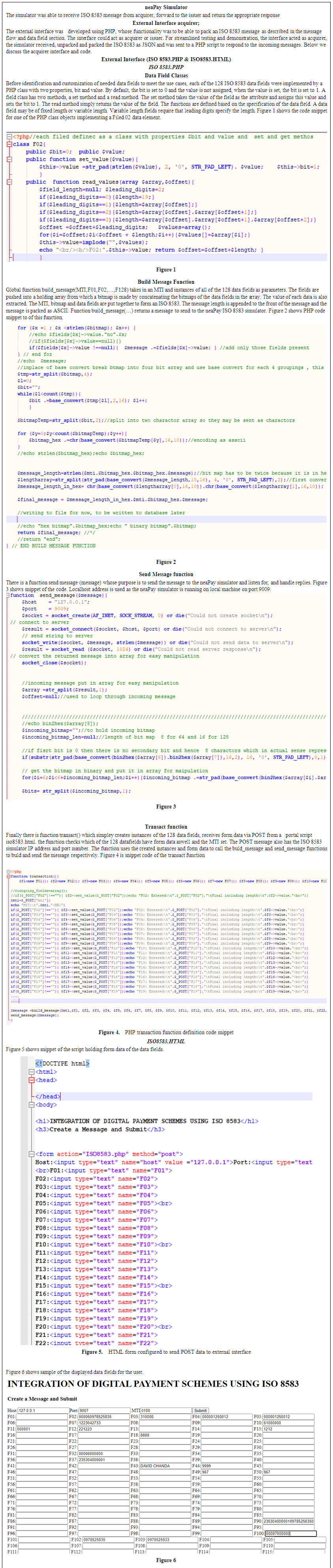

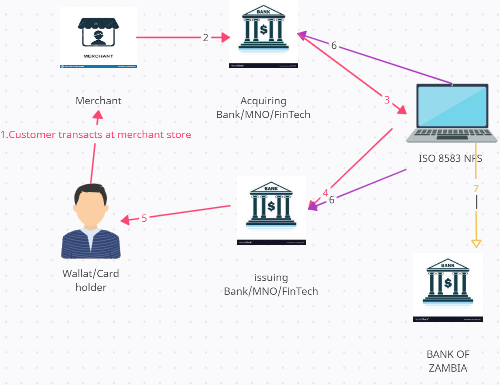

4.4. Current Business Process in Digital Payment Integration

- In the current card network as depicted in Figure 6, transaction processing is in three stages.1. Transaction Authorization (1-5): in this stage, a consumer makes a payment at a store by presenting their debit card to the merchant. The merchant reads card data and generates an ISO authorization message to the NFS, the NFS uses the data fields to route the transaction to the card issue who authorizes the transaction and sends a response to the merchant through the same channel. This happens online.2. Clearing (6): In this stage, at the end of the business day, the NFS aggregates transactions and comes up with net positions for each participant. This stage is offline. They then share the summary and detailed report files with the participants via Secure File Transfer Protocol (SFTP).3. Settlement (7): The NFS then sends settlement instructions to the Bank of Zambia (BOZ) to debit or credit a participant. It’s worthy to note that non-Bank participants, are not allowed to have an account at BOZ, and hence would have to find a sponsor bank which will be receiving settlements on their behalf.

| Figure 6. Debit Card Ecosystem business process in Zambia |

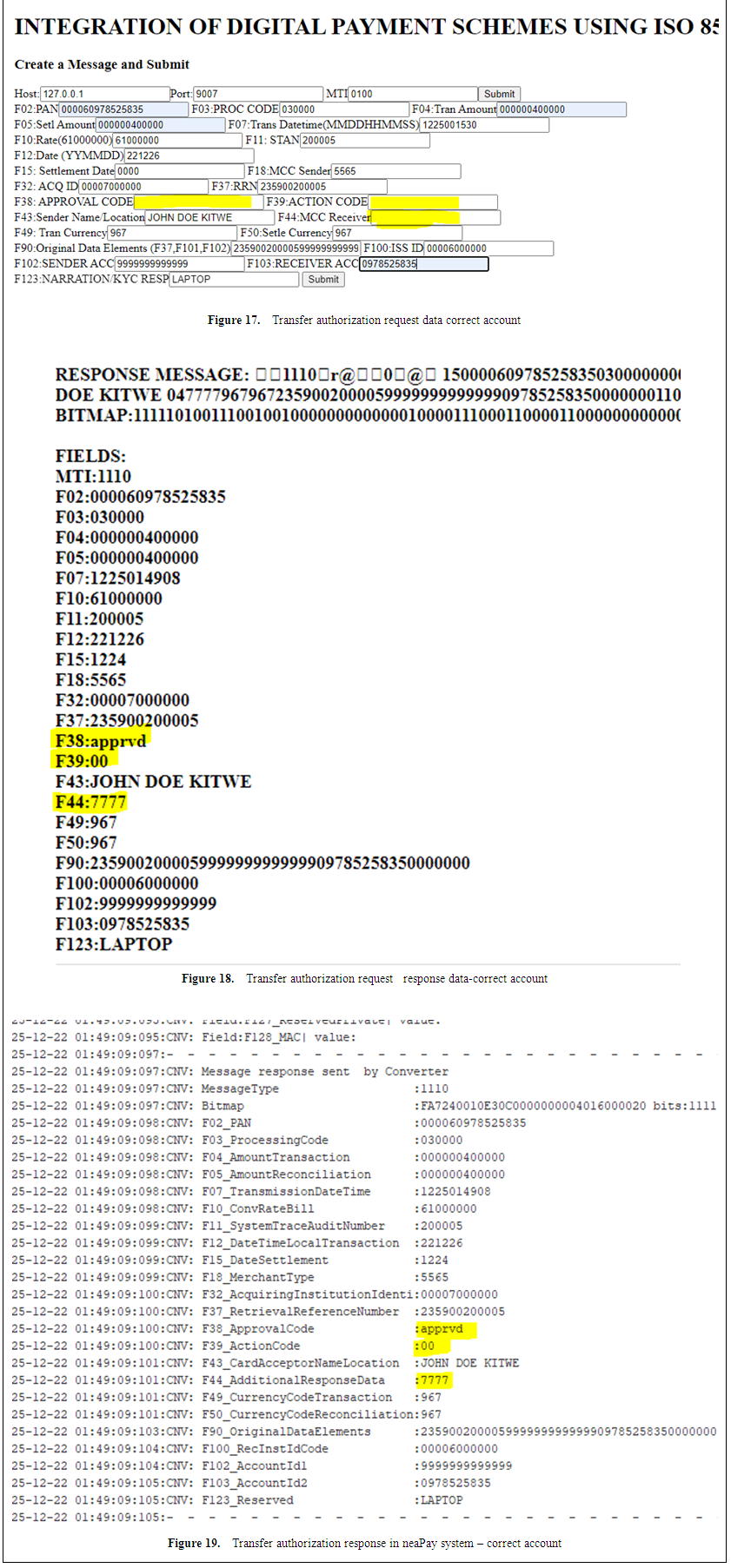

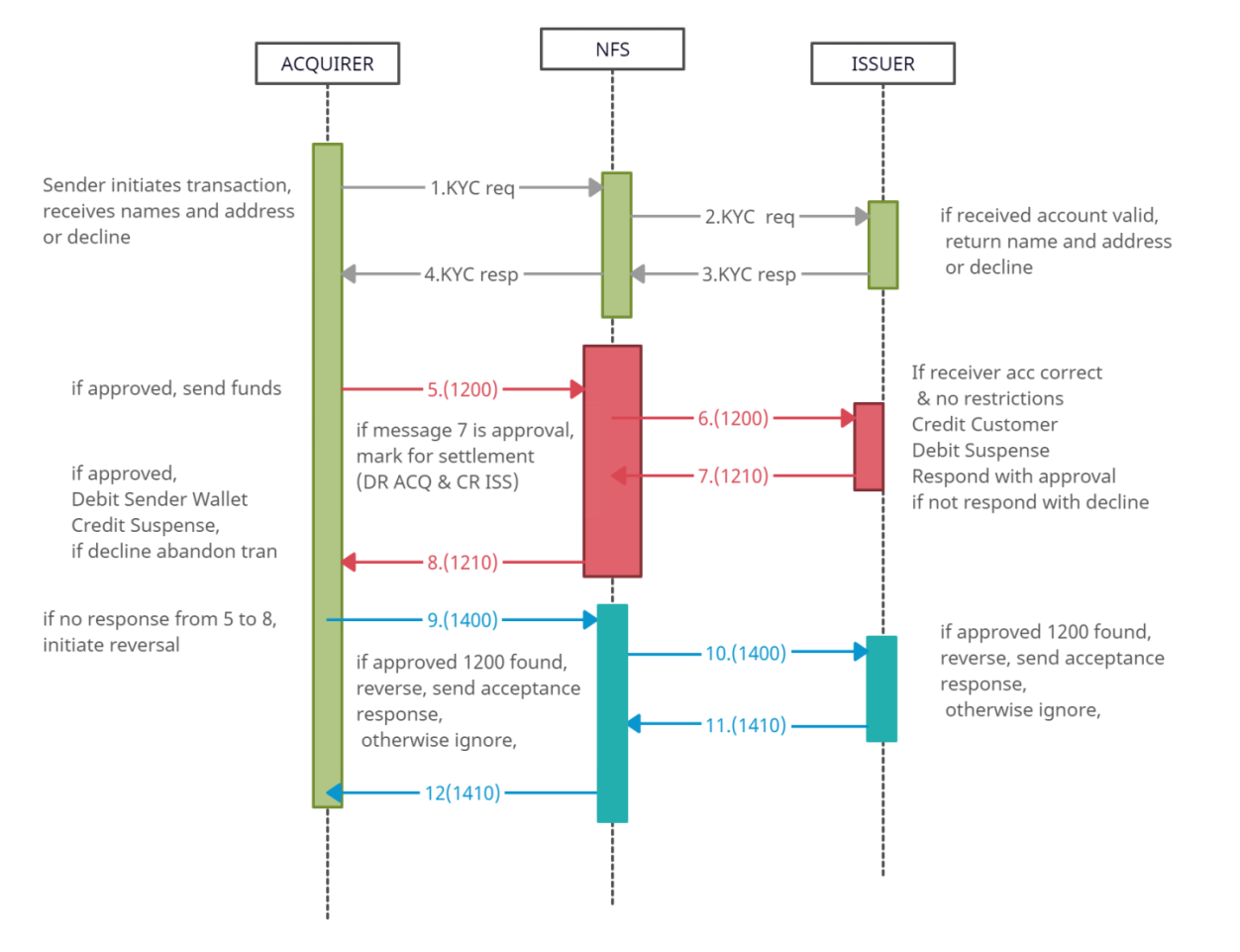

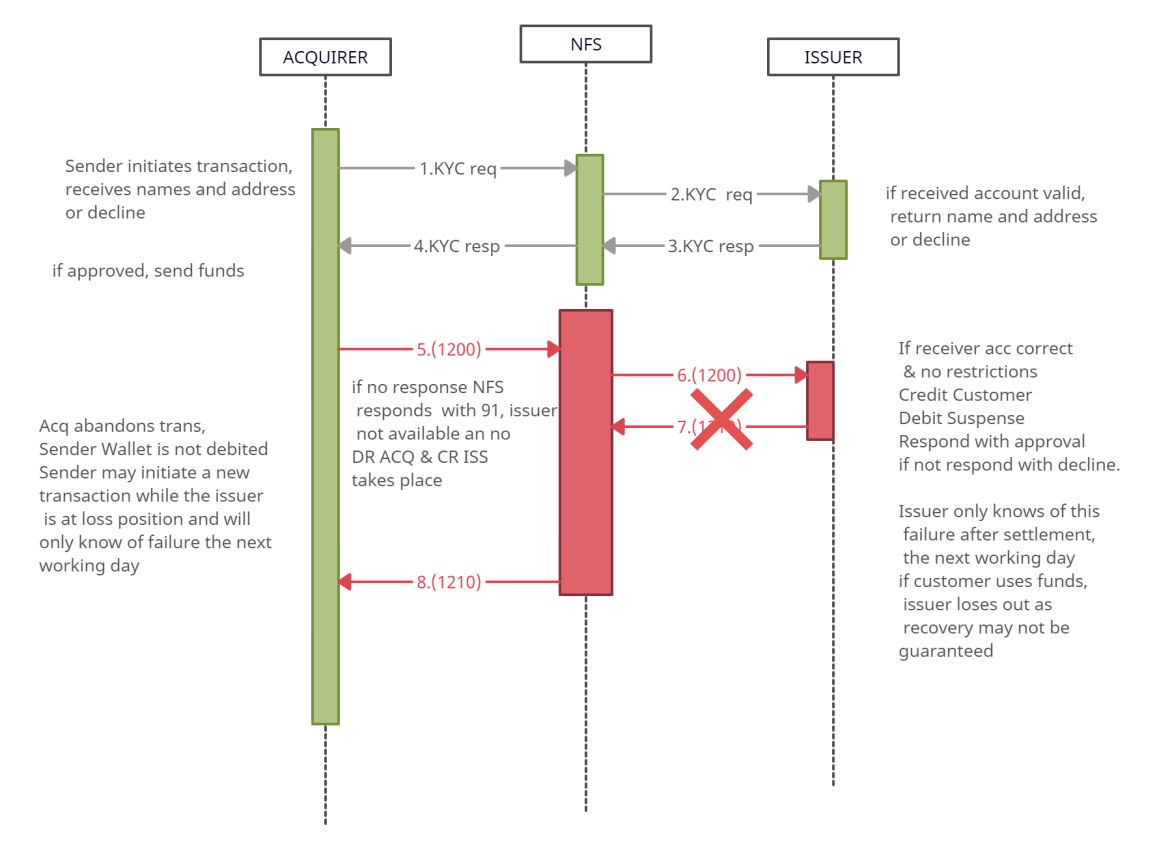

4.5. Current Implementation (NFS E-Money) with Financial Exposure Challenges

- Engagement with the ZECHL had revealed that ZECHL [33] [34] had started a similar project of interconnecting MNO, Fintech and Bank wallets using ISO 8583 using the architecture depicted in Figure 7. However, their use cases were currently limited to transfers, deposits and withdrawals as opposed to consumer payments, and introduced financial loss to the participants when a transaction message is lost. The financial loss is because traditionally, ISO 8583 allows the authorizing party (issuer) to debit their customer and await settlement as opposed to crediting the customer then await settlement. When there are timeouts or dropped messages, the issuer faces financial loss risk as they would have to recover from the customer, hopping the customer would still have funds. Figure 7 shows the message flow for all transfer use cases and the cash in use case alluded to earlier. The acquirer then sends a balance enquiry to the issuer as depicted by message 1 to 4 in figure above. The ISO8583 balance enquiry message returns the receivers Know Your Customer (KYC) details, simply put, their name and address. This gives chance to the sender to confirm they are about to send funds to the intended recipient.

| Figure 7. Current Message Flow (Transfers and Cash-in) |

| Figure 8. Failure at message 7 |

| Figure 9. Failure at 8 |

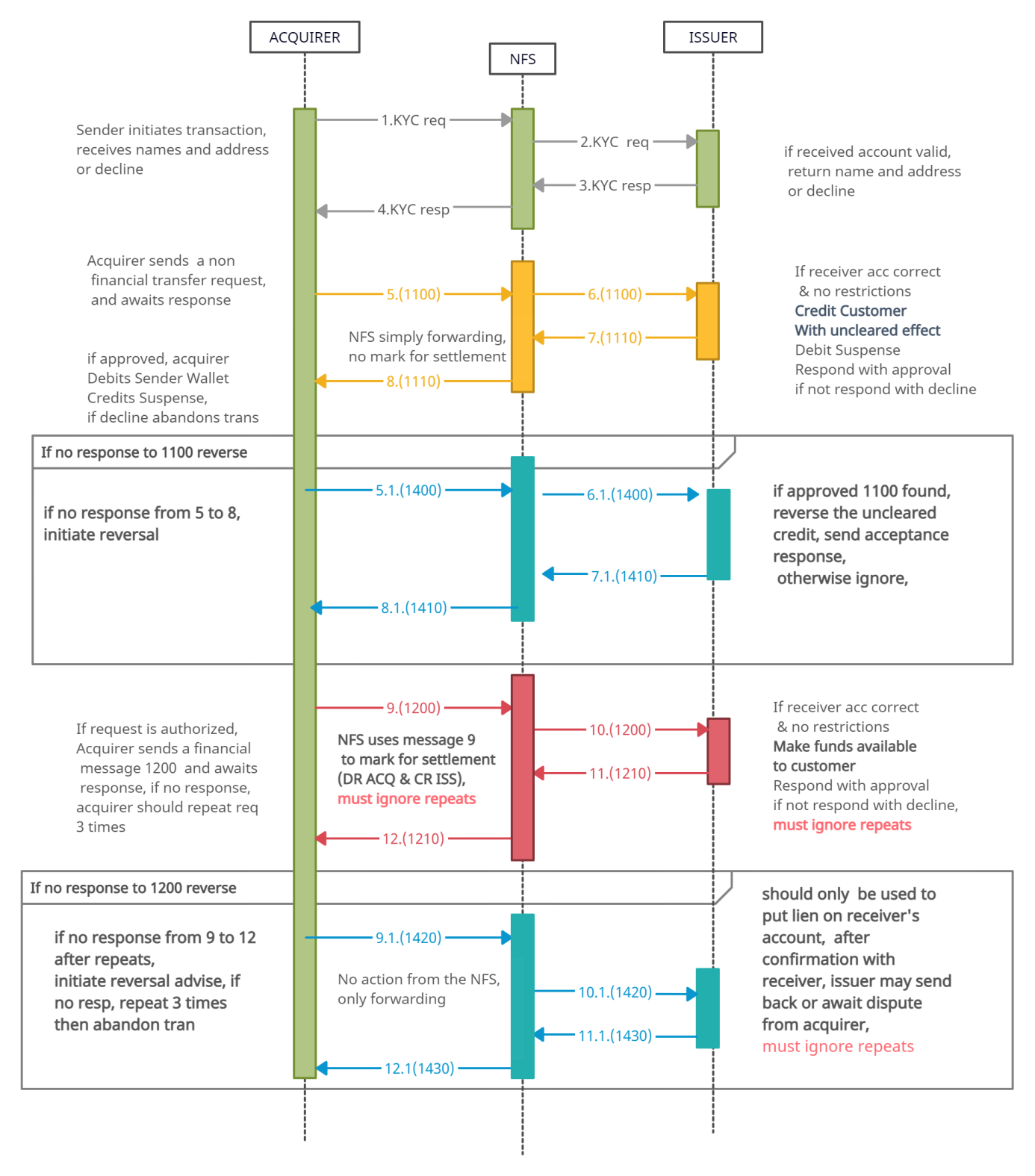

4.6. Proposed Integration Model

4.6.1. Message Flow Customization

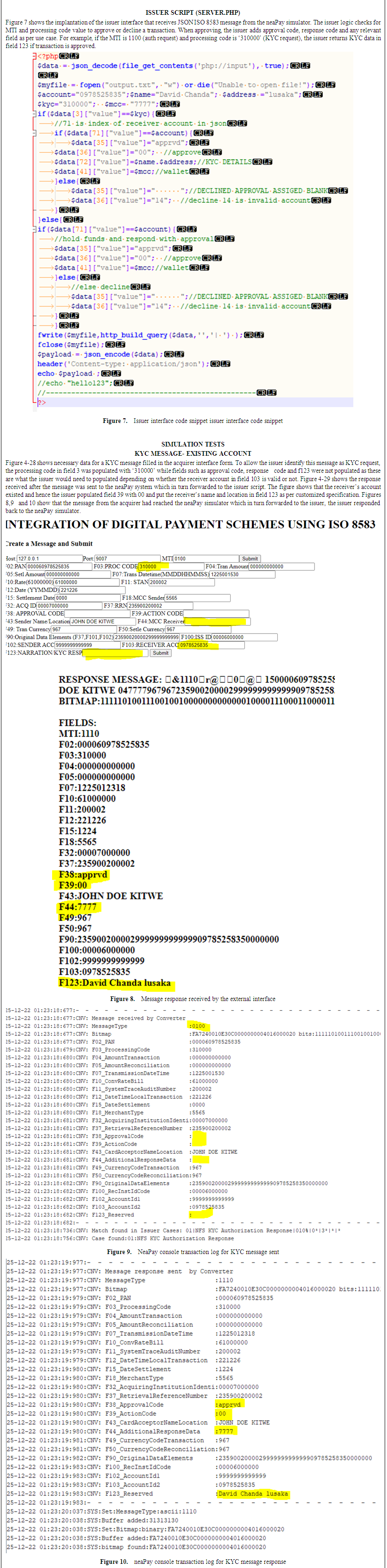

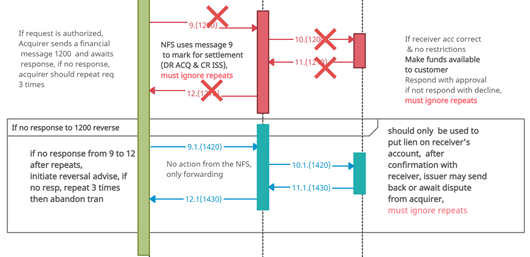

- In the customization of ISO 8583 fields the acquirer and issuer shall be defined as follows.Acquirer: This shall be the initiator of the transaction, will stand in for the buyer (consumer). The acquirer will be debited at settlement.Issuer: This shall be the party that responds to the acquirer initiated message and will stand in for the seller (merchant). The issuer shall be credited at settlement.The proposed architecture involved changing the current message flow as depicted in Figure 7 to accommodate for lost messages without exposing any participant to financial losses.This involved the introduction of an ISO 8583 authorization message (1100) after the KYC message as depicted in Figure 10. The purpose of the authorization message was to allow the issuer credit the receiver with un-cleared effect, that is the receiver does not have access to the money at this point. The issuer then proceeds to respond to the authorization message with an approval. Upon receipt of approval of the authorization message, the acquirer can debit the sender wallet and credit a suspense account then proceeds to send a financial message 1200 and awaits response. The NFS shall use the incoming 1200 from acquirer to mark for settlement (Debit acquirer and Credit Issuer) and forward the 1200 to the issuer. The issuer uses the 1200 to make the earlier credit to receiver available for use, and sends acceptance response to the acquirer. The response to acquirer is basically advisory and would not prompt any action by the NFS nor the acquirer in terms of debits to the sender and acquirer respectively. If any of the messages from 9 to 12 are lost, the acquirer may initiate a reversal.

| Figure 10. Proposed integration model |

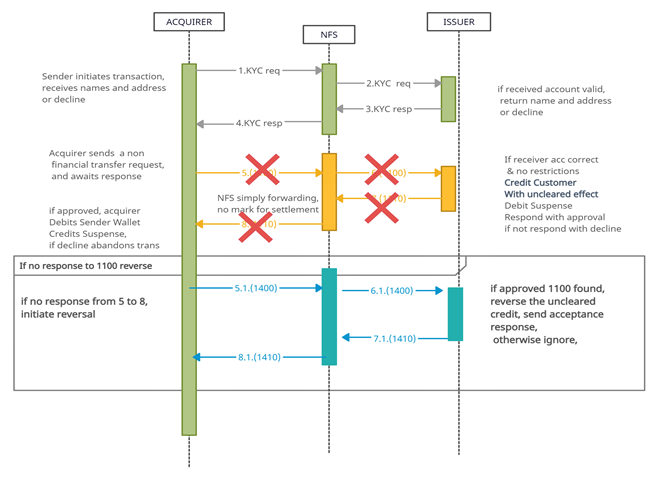

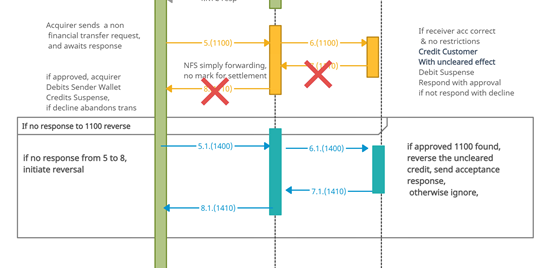

4.6.2. Message Failure Scenarios

- Failure at KYC level: Failure at any of messages 1 to 4 will result in acquirer timing out and restarting the transaction. Failure 1100 level: For failures at messages 5 or 6, the acquirer will time out and send a reversal 1400. Because no prior 1100 would be found, the issuer would ignore this reversal and there would not be any impact on any participant. The NFS simply forward the message in this case.Failure 1100 level messages: For failures at 7 or 8, the acquirer times out and send a reversal. In this case the issuer reverses the credit with un-cleared effect which was earlier passed to the receiver. The funds would always be available because the receiver did not have access to them. The NFS simply forward the message even in this case as in figure 11.Failure at 1200 level: After sending a 1200 and there is no response, the acquirer repeats the 1200 three (3) times after each timeout. The NFS and issuer must retransmit responses any prior 1200 was received. If there is no response after the third attempt, the acquirer may initiate a non-financial reversal advice 1420. The reason acquirer cannot send a financial impact reversal, is to protect the receiver from dishonest senders who would initiate a reversal after a successful transaction. The 1420 reversal advice may be used by the issuer to put a lien on the recipient’s account pending intervention. The specific actions are depicted in figures 11, 12 and 13 and described in next paragraphs.

| Figure 11. Failure at messages 5 or 6 |

| Figure 12. Failure at messages 7 and 8 |

| Figure 13. Failure at messages 9 to 12 |

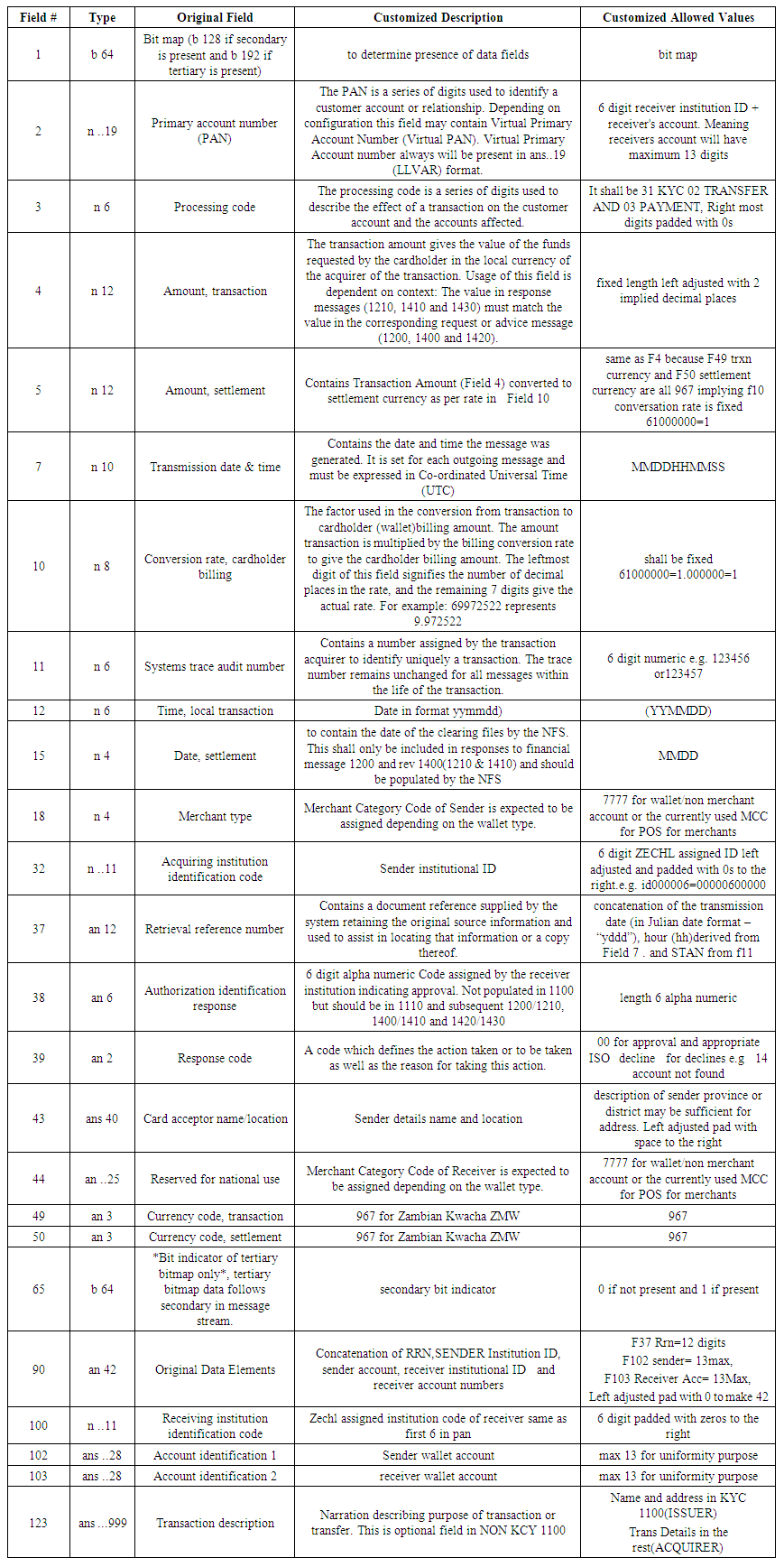

4.6.3. Data Field Customization

- Data Fields and Data fields Population: out of the 168 ISO 8583 data fields, 25 were identified to be sufficient to meet the consumer payments use cases. These fields where redefined, and rules placed for population in requests and responses of the messages. Additionally, four types of message request/response pairs were identified as necessary. These Message Type Indicators (MTI) of these messages were 1100/1110-KYC, 1100/1110-payment request, 1200/1210-settlement, 1400/1410-reversal request and 1420/1430-reversal advice. The identified and customised data fields were as follows (comma separated) F1,F2,F3,F4,F5,F7,F10,F11,F12,F15,F18,F32,F37,F38,F39,F43,F44,F49,F50,F65,F90,F100,F102,F103 and F123.Detailed contents of this customization are found in annexure 1. The annexure shows redefinition of each of the 25 identified fields and the routing and field population rules per message type.

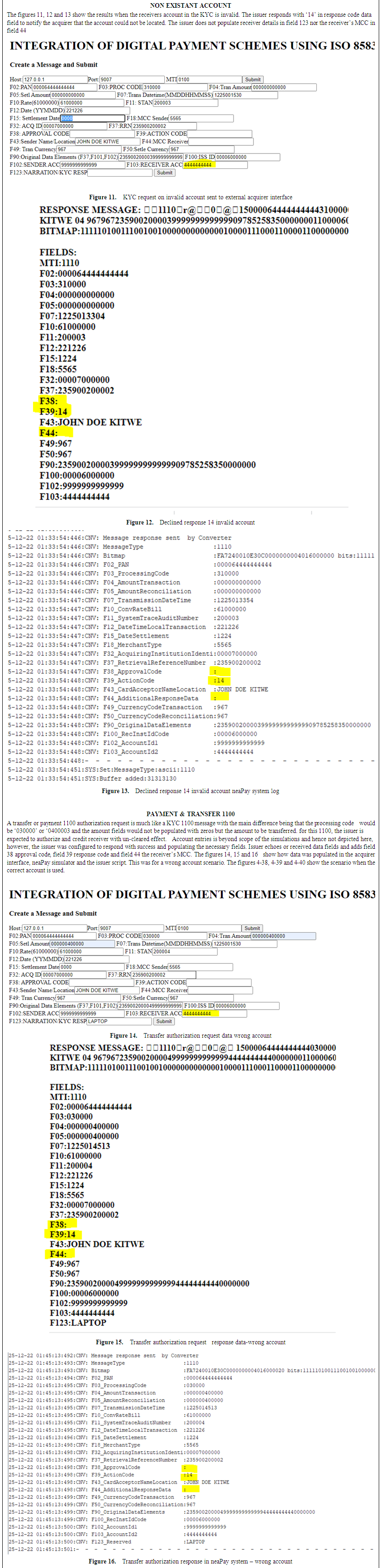

4.6.4. Testing and Validation

- Testing and validation of the model involved development of a prototype model as per architecture in figure 14. To mimic the real world scenario, neaPay ISO8583 simulator from neaPay payment solutions was used to represent the switch at the NFS. To mimic an acquirer and issuer, two prototype interfaces were developed in PHP. The acquirer populated fields in an HTML form as per defined population rules, while the neaPay simulator and issuer interface would be configured to respond to messages as per message flow and data field population rules in Annexure I. The results and explanations of the simulations are contained in annexure II. The source code of the PHP interfaces is added in annexure III. The source code is able to run on any Wamp server supporting PHP 7.

| Figure 14. Prototype Architecture |

4.6.5. Clearing

- The currently existing setup where participants access a designated SFTP site to receive their clearing files shall be maintained. The NFS shall generate and share clearing files with participants for each business day. The files shall contain summaries and detailed reports for each transaction that qualified for settlement. Additionally the detailed files shall also indicate any reimbursement fee or switching fee levied on a participant.

4.6.6. Settlements

- Like in clearing, the NFS shall maintain the currently existing settlement setup where they send settlement instructions to BOZ to debit or credit a participant based on the net sum of a business day’s transaction. The NFS should not combine several business day but send separate instruction for each day. This shall help with streamlined reconciliation by the participants. Non-Bank participants with no settlement account at BOZ shall find a sponsoring bank to stand in for their settlement obligations. To protect sponsors, the NFS should have a configurable that allows the sponsor to a daily debit limit tied to the sponsored members’ collateral or other similar assets deposited with the sponsoring bank. This means as the NFS is processing 1200, cumulative successive 1200 per participant should be noted and if a participant reaches a certain limit, further 1200 from that participant would be declined.

4.6.7. Transaction Dispute Resolution and Reconciliation

- The NFS should support dispute resolution through the Data Navigator system that is currently being used for ATM and POS. The NFS may facilitate revision and annexure to the existing dispute rules, dispute resolution guidelines for the non ATM and POS transactions. This is important as the transactions are push and not pull and hence liability shifts would have to be re aligned.

4.6.8. Participant on Boarding Procedure

- The currently prescribed on boarding process by the NFS and BOZ shall be followed. Each member must apply to the Bank of Zambia for a Certificate of Designation before engaging the NFS. After meeting the requirements and successfully obtaining the certificate of designation from Bank of Zambia, the member shall then apply for membership on the NFS and would have to meet the prescribed requirements before they are on boarded.

4.6.9. Operational Aspects

- Cost: The model resolves the N-squared integration problem in the ecosystem. This transcends into reduced management of all aspects of integration from the payment facilitating companies. This reduction in operational costs results in cheaper services offered to merchants and consumers further stimulating the use of cashless payments.Profitability: reduction in costs implicitly translates into greater profit margins. While higher volumes introduced by more usage from reduced costs also results in higher reurns, further attracting more investments into digital payment solutions using the integration model.Security: A central integration point allows for the regulator to easily control security standards of the ecosystem. The NFS is PCDISS and ISO 27001 security standards certified. Participants joining the ecosystem are also required to subscribe to such minimum security standards and continuous audits to ensure conformant to these standards. There are other related security standards that could be easily introduced such use of HSMS and latest encryption standards.

5. Conclusions

- The study highlighted that ISO 8583 could be used to interconnect payment companies. This would be feasible as it would leverage on the existing infrastructure at Zambia Electronic Clearing house. The study showed that there was little integrations of payment companies in Zambia. This was attributed to lack of integration model that tackled issues around profitability, security, integration standards and regulation. The study demonstrated that an integration model would need to consider merchant and consumer sentiments towards digital payments. Merchants should be encouraged through to use digital payments as it comes with a lot of benefits for them. The study showed that customizing the ISO 8583 as per defined message flow and data element customization in this report would resolve most of the afore mentioned challenges and allow integration. Integration would result in the ultimate goal of having more transactions being cashless in Zambia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Many challenges were faced in finishing this research; it is worth noting the persistent encouragement, support and patience from my supervisor Dr. Simon Tembo. I wish to also thank friends, family and colleagues who gave various support throughout the whole process.

Annexure I: Data Field Customization

- Table 1 contains data field customization of the existing ISO 8583 interface specification at the Zambia Electronic Clearing House. The field customization concentrated only 25 necessary data fields to facilitate transfer the KYC, payment and transfer use cases, it excluded network specific data fields such as those used to encrypt for example the Acquirer Working Key (AWK) and the message header fields that detect the source of the message such as POS, ATM or E-Money. The actual implantation may include for fields as required by the NFS functionality.

| Table 1. Data Field Customization |

| Table 2. Routing and Data Field Population per Message Type |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML