-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2019; 9(1): 19-26

doi:10.5923/j.re.20190901.03

Relationship of Hotel Energy Management Strategies and Hoteliers’ Perception on Sustainable Energy Management in Abuja Nigeria

A. I. Shehu, I. I. Inuwa, I. U. Husseini, Ibrahim Yakubu

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Bauchi, Bauchi State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: A. I. Shehu, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Bauchi, Bauchi State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

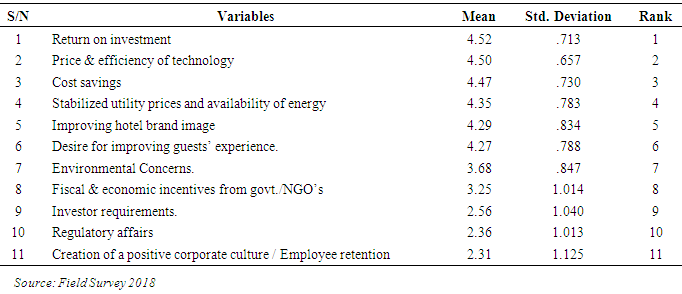

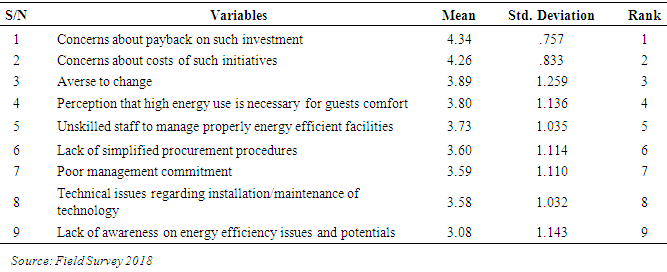

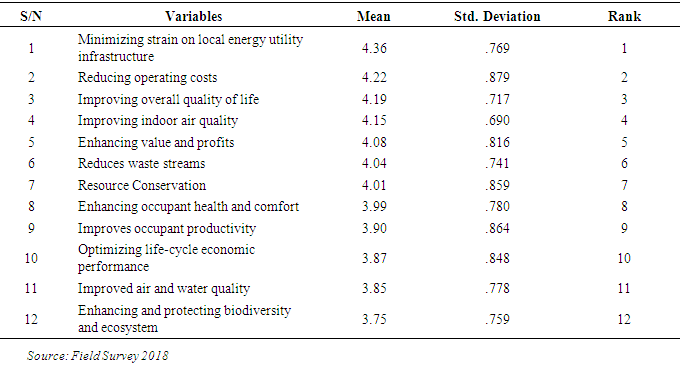

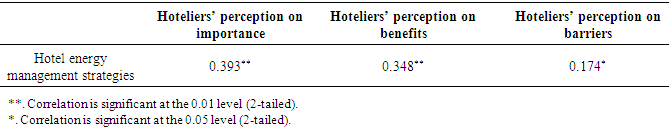

This study examines the relationship of hotel energy management strategies (HEMS) and hoteliers’ perception of sustainable energy management (SEM) in Abuja, Nigeria. Questionnaires were administered while descriptive and inferential analyses methods were applied. The combined respondents mean ranking on application of HEMS revealed timely implementation on preventive and major maintenance programs, educating staff and guests on energy consciousness, frequent insulation assessment ranked (3.57-4.27) as applied HEMS. Setting energy conservation target and energy audits ranked moderately applied (3.34-3.36) while installing centralized energy management systems, on- site renewable energy generation, smart digital thermostats installation ranked (1.57-2.15) were least applied. The result further demonstrates return on investment, price and efficiency of technology, cost savings, Stabilized prices and availability of energy, improving hotel brand image and desire on improving guests’ experience ranked (4.27-4.52) as important factors encouraging adoption of SEM. Environmental Concerns and Fiscal/economic incentives ranked (3.25-3.68) were moderately important while investor requirements, regulatory affairs and creating positive corporate culture/employee retention ranked (2.31-2.56) were least important factors encouraging the adoption of SEM. Moreover, all identified barriers ranked (3.08-4.34) were either severe or moderately severe. Hoteliers also ranked all the identified benefits of SEM as beneficial (3.75-4.36) to hotels management for energy sustainability attainments. The correlation results revealed moderate positive correlation between HEMS and both Hoteliers’ perception on importance and benefits of SEM at r=.393 and r=.348 respectively. However weak positive correlation was found between HEMS and hoteliers’ perception on barriers to SEM at r= .174. The study thus recommends that deserved cognizance be given to identified least applied but vital HEMS and also improves hoteliers’ perception on importance, barriers, and benefits of SEM for effective hotel energy management.

Keywords: Energy management Strategies, Hoteliers’ Perception, Sustainable energy management

Cite this paper: A. I. Shehu, I. I. Inuwa, I. U. Husseini, Ibrahim Yakubu, Relationship of Hotel Energy Management Strategies and Hoteliers’ Perception on Sustainable Energy Management in Abuja Nigeria, Resources and Environment, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 19-26. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20190901.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The increasing global energy consumption is contributing to greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions that are central to global warming problem [20, 24]. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that residential, commercial and public buildings account for 30% to 40% of world’s energy consumption that contributes 25% to 35% world’s carbon iv oxide (CO2) emission [1, 37]. Hotels are rated high among energy consuming public buildings [4, 15, 32]. They consume energy to meet the broadened demands for space heating, cooling, and ventilation, heating water, lighting, laundry, kitchen, recreation and miscellaneous. Their diversified energy resources consumption is responsible for approximated harmful CO2 gas emissions of between 160kg to 200 kg per square meter of room floor area [2, 31, 12]. Abuja the administrative capital of Nigeria is among cities with the highest numbers of global hotel brands. This is expected to grow with the recent increase in interests in hotel and hospitality businesses [21]. Moreover, this highlights a significant improvement compared to the estimated drop in the average hotel occupancy rate across the major cities by around 60% – 65%, from a high of 80% in 2008 attributed to heightened insecurity [13].However, the challenges are not limited to insecurity but also to the Nigerian electricity supply which has been characterized as inadequate and unstable for decades induced by an overburden and failing energy system. This situation earned the country lowest rating in per capita electricity consumption in Africa [28, 1] and manifests in the high incidences of power outages forcing a large portion of industries, businesses, and households to rely on diesel and petrol generators for primary or back-up source of electricity, which is expensive and constitutes source of noise and air pollutions [14]. In view of the foregoing, the hospitality industry is among the hardest hit because their nature of operations requires energy for 24 hours, irrespective of season and number of guests accommodated and as well upon which the hotels depends to deliver affordable services [5]. Thus energy resources are vital assets of hotel organisations that require proper management for effective achievement of organizational objectives. Moreover, this relevant nowadays because several studies indicated that the increasing prices of energy resources and growing pressure from governments and stakeholders prompted lodging operators to enhance energy efficiency in their properties [8, 14, 33]. This development in the hotel industry is further driven by multiple factors which includes owners and operators desire to reduce operational costs, changing investor attitudes toward the environment and the coinciding emergence of corporate social responsibility programs, increased regulatory focus on facility operations and development, and a general shift towards the paradigm of sustainability [8].The trend activated an increased consciousness of efficient energy management that ensures energy sustainability amongst hoteliers and investors particularly in developed economies in the process of hotel development as well as operations of hotel facilities. Nonetheless, a review of studies conducted on hotel energy management strategies and hoteliers perception on sustainability shows few numbers of studies covering Nigerian hospitality industry. Moreover studies conducted by [8, 17, 26] were conducted in developed and stabilized economies, with vibrant industrialized systems where nowadays the issue of sustainability in every industry is a priority in the business action plans, however, this research cannot find similar studies carried out in a depressed economy like Nigeria that is directed towards providing empirical relation between hotel energy management strategies and hoteliers’ perception on sustainable energy management. Hence, this study examines the relationship of hotel energy management strategies and hoteliers’ perception on sustainable energy management in Abuja Nigeria. The study outlined the following objectives:i. To assess the level of application of hotel energy management strategies in Abuja, Nigeria.ii. To assess hoteliers’ perception on the importance of sustainable energy management in Abuja, Nigeria.iii. To assess hoteliers’ perception on barriers to sustainable energy management in Abuja, Nigeria.iv. To determine the relationship of hotel energy management strategies and hoteliers’ perception on sustainable energy management in Abuja, Nigeria.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Construct

- The theoretical construct of this study is based on the fundamental principles of sustainable development which entails sustainable energy management that is aimed at resource conservation, environmental protection, and cost savings that provides energy security (sufficient, safe, and affordable) for present and future generations [13]. Currently, energy efficiency, energy conservation and renewable energy integration characterized the concept of energy sustainability [3, 15]. Thus, hoteliers’ perception towards the concept equally plays a significant role in ensuring hotel operational performance, particularly in relation to hotel energy management strategies for effective achievement of energy efficient hotel industry. In recognition of the significance of perception Festinger’s (1957) theory of cognitive dissonance postulates that all individuals seek cognitive consistence by reducing contradictory thoughts and emotions, so as to bring them into harmony [38]. Based on this theory, it can be deduced that the relevance and acceptance of a criterion should be consistent. It can be presumed, furthermore, that when someone attaches more importance to a criterion he or she is then led to have a higher acceptance of it and vice versa [11].

2.2. Hotel Energy Management Strategies (HEMS)

- Studies indicated that hotels rank among the top five in terms of energy consumption in the commercial building sector [33, 28, 40]. However, energy use in most buildings is known to be highly inefficient, with large heat losses through poorly insulated walls, roofs, windows and heating pipes, poor management of lighting, and design features that necessitate excessive energy use for both heating and cooling [12, 10].Energy resources is one of the assets of a hotel need for a manager to decide how best to use them to achieve an organizational objective. Especially nowadays as several studies indicated that the increasing prices of energy resources and growing pressure from governments and stakeholders provided increased motivation to lodging operators to enhance energy efficiency in their properties [33]. With regard to the hotel industry as one of the major sectors of the hospitality industry, they need a base load of energy that forms a fixed cost to operate equipment such as heating, ventilation, cooling and lighting regardless of the number of guests staying at the hotel.Various initiatives have been established to encourage the tourism industry and hotels in particular, to improve their energy performance and environmental impacts. In addition to adopting various strategic initiatives, review of the energy strategy is also vital. Reviewing the use of energy within a hotel not only provides the opportunity to identify where savings can be achieved for the business prosperity. An improved energy strategy can also enhance the corporate reputation of a hotel brand through the reduction of carbon footprint and its impact on the environment [22, 39]. Auditing a hotel use of gas and electricity, as well as gaining a detailed understanding of employees’ and customers’ knowledge of energy consumption will enable the establishment of an improved strategy that will yield numerous benefits.

2.3. Hotel Energy Management Programme

- Energy management is normally organized in a similar manner to water management in a hotel [16, 35]. However, as demonstrated earlier, energy use in a hotel building is normally by various hotel engineering services systems; energy management is therefore more complicated and difficult than water management. Fundamentally, energy management is more technically biased and should therefore be directed more towards engineering staff.The key elements of a successful energy management programme can be summarized as managerial and technical [35]. The Managerial element opined that energy management should be fully integrated into hotel’s overall management systems and treated with equal importance to other management functions. Hence, there should be a clearly defined energy use policy and action plan, with the responsibility for implementation vested in a senior executive or an energy manager if appointed. This will require the training and involvement of all staff to participate in energy management. Moreover, good housekeeping practices should be exercised in all departments while data or information on energy use and its associated cost should be regularly communicated to staff to raise their awareness of energy conservation issues.The Technical element on the other hand focus on allowing part of annual operating budget for upgrading the existing engineering systems, with particular emphasis on upgrading energy intensive equipment’s such as air conditioning, chillers, and air handling units [35]. As well carrying out energy audits on a regular basis, preferably once a year, and installing or adding suitable electricity and gas sub-meters to monitor energy use in various electricity end-users and in kitchens, thus facilitating the breakdown of the total energy use to identify major end- users. It includes educating and training engineering staff to be aware of the effect of their operational activities on energy use. It involves establishing a well- defined operation and maintenance programme for engineering staff, so that waste can be curtailed [35]. It also covers adopting technically advanced energy efficient equipment including lights, chillers and energy efficient motors, etc. [23].

2.4. Approaches to Sustainable Energy Management (SEM)

- Energy sustainability can be approached in two different ways: technological and behavioural [6, 25]. The former involves changing or replacing the outmoded technology to new and more efficient ones while the later entails how users behave and use energy [25]. Both approaches are often considered under ‘end-use efficiency’ and ‘demand-side management’ respectively [34]. Putting the hotel Facilities in perspective, the behavioural approach leaves the management with no control over individual’s behaviour towards energy usage and obviously, the customer have little or no stake in relation to its costs. But the two approaches i.e. can be managed through the following techniques.

2.4.1. End-Use Efficiency

- End-Use efficiency refers to technologies, appliances or practices that improve the efficient use of energy at the level of the final user for example, the appliances in offices and homes [27, 14]. End-Use efficiency is not limited to electrical appliances as it can also be used for other areas of efficiency such as measures to improve the ability of the building to absorb and retain heat in the cold seasons and keep out heat in the hot season [1, 13]. Improved end-use technologies and practices can be substituted for less efficient ones thereby reducing electricity demand and generation; among the three segments of electric energy system generation, delivery and end-use. End-use offers the greatest near-term potential for large increases in efficiency [34]. End- uses in buildings can be for cooling, ventilation, lighting, cooking, plug loads and others.

2.4.2. Demand-Side Management (DSM)

- DSM is a set of interconnected and flexible programs by utility companies and energy planners which allow customers a greater role in shifting their own demand for electricity during peak periods and reducing their overall energy consumption [10, 34].Demand-side management programs comprise two principal activities which are; demand response programs or “load shifting” and energy efficiency and conservation programs [30].Due to this advantage of flexibility it offers, the technique ushers greater potentials in reducing energy consumption of hotel facilities and by implication reducing their operating costs. Some DSM techniques used today involves; night-time heating, direct load control, load limiters, commercial/industrial programs, frequency regulation, time-of-use pricing, demand bidding and smart metering [34]. An example is the implementation of the use of prepaid meters (smart metering) in buildings stand to reduce the consumption of electricity.Despite the advantages and huge potentials involved in adopting the DSM approach, it is faced with various challenges [19] such as lack of ICT Infrastructure; DSM requires much intensive deployment of various sensor and advanced measurement and control devices. Although key elements of technology exist, targeted trials are required to gain experience with DSM network operation; Electricity demand patterns start shifting in unpredictable ways; lack of understanding of the benefits of DSM solutions; DSM-based solutions are often not competitive when compared with traditional approaches; DSM-based solutions increase the operational complexity of the system when compared with traditional solutions, and inappropriate market structure and lack of incentives.

3. Methodology

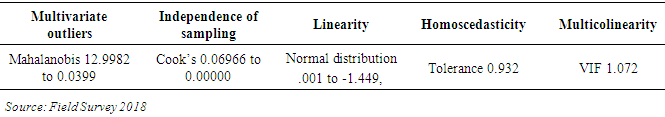

- The study adopts quantitative research design which covers both exploratory and descriptive methods. The questionnaire was pretested by 10 academics for validity, as well as tested for reliability using Cronbach’s alpha and it records 0.7; revealing that it is reliable. Thereafter, 5 copies were disproportionately administered to 4 senior technical staff of rated hotels within the eight (8) districts of phase I Abuja, Nigeria. The staffs were drawn from 24 hotels out of a sample frame of 25 hotels in accordance with Krejcie & Morgan (1970) sampling table. They were selected in each of the 24 hotels operational departments of housekeeping, engineering and maintenance, food and beverages, and accounting. This staffs are knowledgeable in the hotel energy use and management. The hotels studied are those that conform to the standard descriptions encapsulated in the national classification and grading of hotels provided by Nigeria Tourism Development Corporation. The questionnaire survey records 86% response rate and data collated were subjected to descriptive and inferential statistics using mean ranking and Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Likert scales of 1-5 were used to capture the opinions of respondents on the application of HEMS and perceptions of SEM in Abuja Nigeria respectively. The scales are interpreted in the order of the objectives, as:i. Application: mostly applied (4.5-5.0); applied (3.5-4.44); moderately applied (2.5-3.44); least applied (1.5-2.44); & not applied (0.0-1.44).ii. Importance: very important (4.5-5.0); important (3.5-4.44); moderately important (2.5-3.44); least important (1.5-2.44); & not important (0.0-1.44).iii. Barriers: extremely severe (4.5-5.0); severe 3.5-4.44); moderately severe (2.5-3.5); least severe (1.5-2.44); & not severe (0.0-1.44).iv. Benefits: highly beneficial (4.5-5.0); beneficial (3.5-4.44); moderately beneficial (2.5-3.44); least beneficial (1.5-2.44); & not beneficial (0.0-1.44).Table 1 depicts preliminary analyses in respect of multiple correlations. The table reveals that there were no violation of the assumption of normality, linearity and homoscedasticity, because the values obtained are less than 13.83, 1, and10 which are the critical values for evaluating Mahalanobis distance, Cook’s distance and VIF(variance inflation factor) respectively [29]. Moreover, skewness and kurtosis are within acceptable ranges of +-2 while tolerance is above 0.1 for linearity and homoscedasticity respectively [7, 29]. The magnitude of the relationships reported were interpreted using Burris (2005) descriptors, with coefficient >0.69 as very strong, 0.50 to 0.69 as substantial, 0.30 to 0.49 as Moderate, 0.10 to 0.29 as weak and 0.01 to 0.09 as negligible.

|

4. Results and Discussion

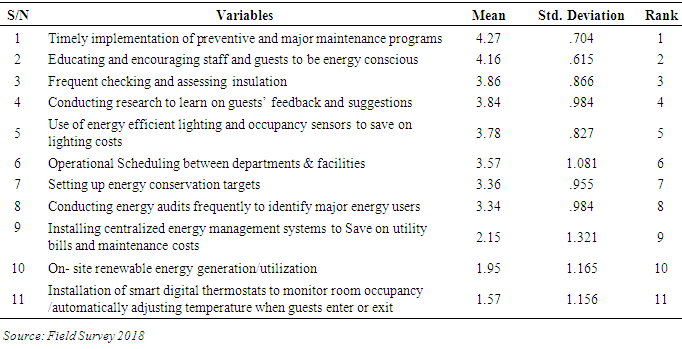

- Table 2: portrays the combined respondents mean ranking of the application of hotel energy management strategies in Abuja, Nigeria. Timely implementation on preventive and major maintenance programs, educating and encouraging staff and guests to be energy conscious, frequent checking and assessing insulation, were ranked by respondents (3.57-4.27) as applied hotel energy management strategies in Abuja Nigeria. Setting energy conservation target and conducting energy audits were ranked as moderately applied (3.34-3.36) while installing centralized energy management systems to save on utility bills and maintenance costs, on- site renewable energy generation/utilization, installation of smart digital thermostats to monitor room occupancy /automatically adjusting temperature when guests enter or exit were ranked least applied (1.57-2.15).

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- i. The study results shows that among the diverse energy management strategies employed by hotels the timely implementation of preventive and major maintenance programs and encouraging staff and guests to be energy conscious prevails. This suggest that less priority being applied to vital energy management strategies such as installation of centralized energy management systems and on- site renewable energy generation thus demands deserved cognizance for sustainable energy management of the hotels.ii. Apparently, energy management strategies and hoteliers’ perception determines hotel energy sustainability represented by the moderate positive relations between the energy management strategies and hoteliers perception on importance and benefits of the concept of sustainable energy management. iii. In spite the weak positive correlation found between energy management strategies and hoteliers’ perception on barriers to sustainable energy management, however the positive association highlights its degree of contribution to the poor energy management status of the hotels, thus the need for an improved hoteliers’ perception on importance, barriers, and benefits of energy sustainability cannot be over emphasized for achieving effective hotel sustainable energy management.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML