-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2018; 8(3): 136-147

doi:10.5923/j.re.20180803.05

Collaboration and Co-ordination of Land Use Planning and Development Control in Kisii Town, Kenya

Wilfred Ochieng Omollo

Department of Planning and Development, Kisii University, Kisii, Kenya

Correspondence to: Wilfred Ochieng Omollo, Department of Planning and Development, Kisii University, Kisii, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Urban development should be informed by a clear strategic collaboration and co-ordination framework in land use planning and development control process. The objective of this study was therefore to examine the extent of collaboration and co-ordination of land use planning and development control processes in Kisii Town. It was anchored on systems theory that visions Kisii Town as a single spatial entity with actors that need to mutually work in harmony towards realizing the objectives of land use planning. Target population comprised of 106 professional staff from the nine departments of the County Government of Kisii in addition to 25 practicing land surveyors. Results showed that as regards collaboration, all departments were not adequately engaged in land use planning and development control processes such as plan preparation and approval of land subdivisions, building plans and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports. Result of Pearson’s bivariate correlation also corroborated a positive linear relationship between extent of co-ordination and attainment of land use planning objectives (r = .621, N= 65, p = .000), showing that as departments collaborated less, attainment of land use planning objectives weakened. Relating to co-ordination, whereas key factors that undermined approval of land subdivisions included lack of strategy and laxity by the County Director of Physical Planning and Urban Development (CDPPUD); disregard of approval procedure by the Land Control Board (LCB) and practicing land surveyors, factors that derailed approval of building plans on the other hand included circumventing of CDPPUD by other departments in approval process. Results of Pearson’s bivariate correlation further showed a positive correlation between extent of co-ordination and attainment of development control objectives, r = .731, N = 65, p = .000, hence, decreased co-ordination impelled a parallel decrease in attainment of land use planning objectives. The study concluded that owing to the administrative lapse in co-ordination and collaboration, a gap that affords developers and practitioners with an opportunity of prompting unregulated land use change ensues, in consequence, negating the objectives of sustainable land use development. A key recommendation was made for the establishment of a County Spatial Planning Co-ordinating Committee (CSPCC) to harmonize and coordinate the institutions and related agencies that participates with land use planning and development control.

Keywords: Land Use Planning, Co-ordination, Collaboration and Kenya

Cite this paper: Wilfred Ochieng Omollo, Collaboration and Co-ordination of Land Use Planning and Development Control in Kisii Town, Kenya, Resources and Environment, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2018, pp. 136-147. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20180803.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Land use planning is a procedural and interactive statutory activity carried out to provide an enabling environment for sustainable development of land resources which meets people’s needs and demands. It is customarily attained by evaluating the physical, socio-economic, institutional and legal potentials and constraints with respect to an optimal and sustainable use of land resources. The intention is to empower people to make decisions about how to efficiently and rationally allocate those resources. In this way, land use planning inspires social processes of decision making and consensus building with reference to the utilization and protection of private, communal or public activities. At the core of land use planning is the balancing of competing interests from different stakeholders in pursuit of a common vision (GIZ, 2012). Nevertheless, a salient problem in planning and allocation of land resources is that different people, institutions or groups, always have diverse expectations on how land resources should be used. For this reason, proper use of land resources depends on how such interests are addressed through effective co-ordination and collaboration framework (Sidor, 2015). International agenda on sustainable management of land resources was clearly articulated during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 1992, that supported a co-ordinated and collaborative methodology to planning and management of land resources. Its target was to establish a guiding context for planning within which detailed sectoral plans could be developed along with establishing intersectoral consultative bodies in each member state to streamline the envisaged policy implementation (United Nations, 1992). The central argument is that for land use planning to be effective, stakeholders with competing interests need to operate in an environment that advocates for strategic collaboration and co-ordination with an intention of attaining a sustainable and orderly spatial development especially in urban areas. From this contextual overview, the study begins by reviewing related literature on collaboration and co-ordination in land use planning. Suffice it to say that good co-ordination and collaboration amongst institutions or actors engaged in land planning and development control ensures that limited land resources are efficiently used, conflicting goals eliminated and overlapping functions reduced.

1.1. Review of Related Literature

- Kimani and Musungu (2010) observed that one of the factors negating land use planning in Kenya was lack of integrated co-ordination and collaborative framework within which various institutions concerned with land use planning could operate. This was aggravated by the fact that legislations scattered in several statutes made it even harder for planners and developers to understand the planning requirements resulting to ambiguities that made physical planning and development control a challenge. A study by Islam (2012) in Dhaka City, Bangladesh, by the same token found out that although 40 different governmental organizations participated in service delivery, there was a problem of co-ordination and collaboration among them resulting to wastage of resources. Even though attempts were made to solve the problem by restructuring the city’s government where all service delivery were brought under a single authority, the arrangement only worked for some time and was discontinued with change in subsequent city government. The study concluded that success in service delivery lied on co-ordination and collaboration among government departments, including political support because effectiveness of urban policies largely depended upon the linkages among institutions responsible for planning and service delivery.While investigating implementation of urban master plans in Rajasthan, India, the case of Alwar City, Mishra (2012) found out that the plan realised little success. Some of the factors contributing to this included lack of co-ordination and collaboration among government agencies as well as poor governance and widespread corruption. These findings compares to that of Opata et al (2013) in Kenya that established that implementation of urban land use development policies was curtailed by challenges such as lack of institutional and intersectoral co-ordination and collaborative framework which was further aggravated by lack of or inadequate participation by beneficiary population. In Uganda, the Uganda Land Alliance (2014) established that although the Land Act provided for the establishment of District Land Boards in each district, the Boards were found to be allocating land without consulting other constitutional committees. This negatively impacted on implementation of the existing physical development plans, leading to land use conflicts. An example was in Nakapiripirit Town where Education Department offices were constructed on land zoned for commercial use as per the town’s structure plan. A related study by Shivanand and Mukundan (2015) in Gujarat, India, also demonstrated that there was unsuccessful co-ordination in land use development planning since responsibilities for providing urban services were fragmented among different agencies. For example, industrial estates were planned and developed by state-level authorities without co-ordination with urban local bodies responsible for providing support infrastructure, such as drainage network and public transport. The study also pointed out that delineation of responsibility and authority was sometimes blurred among planning entities. As regards provision of urban infrastructure within new residential areas in Tehran City, Iran, Yazdani et al (2015) argued that there was barely any form of co-ordination structure in land use planning due to lack of horizontal and external co-ordination. They cited “Mehr”, a wide government housing programme which aimed to provide housing for the low-income citizens pursuant to the Cooperative Economics Law of Iran. Because of co-ordination challenges, this mass production of housing did not achieve desired goals in some parts of Iran. Conflicts between plan implementation institutions are also not unusual in Kenya as noted by Ombati and Mosoku (2015) while reporting about a title deed issued by President Uhuru Kenyatta for establishing the proposed Bomet University College in Bomet County,“…Bomet Governor, Mr. Isaac Ruto has protested the issuance of a title for the construction of Bomet University College, saying the process was illegal and fraudulent. The county government says it had set aside 100 acres in Siongiroi about 50 kilometres out of Bomet Town, but members of parliament in the county are pushing it be set up at the controversial land…And speaking on phone, National Land Commission (NLC) Chairman Muhammad Swazuri said he was not involved in the issuance of the title”.In a quick rejoinder (Njagi & Kimutai, 2015), the Cabinet Secretary responded,“…Acting Lands Cabinet Secretary, Fred Matiang’i, dismissed as misleading and inaccurate claims by Bomet Governor, Isaac Ruto, that the title deed was illegal. He said the title was issued in line with the stipulations of Section 107 (1) and (2) of the Land Registration Act. He said the ministry had prepared titles for Bomet Town Parcel 307 and 308 for establishing the university college on the basis of a request done by the Bomet County leaders. …The claims attributed to the Bomet governor are therefore inaccurate … They should be ignored, said Matiang’i” Above expressions reinforces how absence of co-ordination and collaboration in land use planning may derail implementation of essential projects with significant bearing on socio-economic development agenda. From the literature reviewed, though previous studies generally recognize challenges relating to inadequate co-ordination and collaboration in land use planning and development control, a scarcity in literature is manifest on the specific processes within land use development control, such as land subdivisions and approval of building plans among others, which are not well coordinated, in addition to lacking an effective collaborative framework, a gap filled in the current study.

1.2. Research Objective and Theoretical Underpinning

1.2.1. Research Objective

- From the identified research gap, the objective of this study was to examine the extent of collaboration and co-ordination of land use planning and development control processes in Kisii Town.

1.2.2. Theoretical Underpinning

- This study was anchored on Systems Theory (ST), founded by Ludwig Von Bertalanffy in 1962. According to Mele, Pels and Polese (2010), ST generally examines an entity that is contextualised as a distinct operational unit, rather than the sum of uncoordinated parts. In the current study, ST validates why different actors ought to coordinate and collaborate in addressing the challenges facing land use planning. The theory visions Kisii Town as a single spatial entity consisting of different actors that need to mutually work together in harmony in order to realise the objectives of land use planning and development control through an effective co-ordination and collaboration framework.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Background to the Study Area

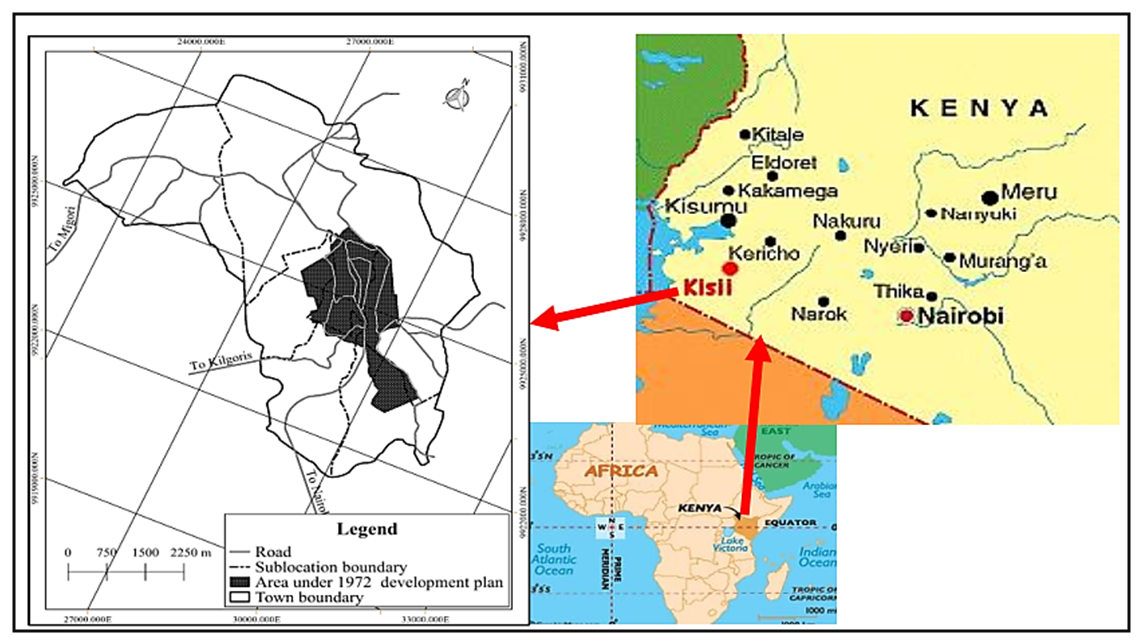

- Kisii Town covers a spatial extent of 34km2 and is situated approximately 400 km West of Nairobi City, the capital city of the Republic of Kenya. It serves as the headquarters for Kisii County, one of the 47 devolved county governments in accordance with Chapter 11 of the Constitution of Kenya (2010). The town’s population currently stands at approximately 93,959 with annual population growth rate of 2.7%. This population is projected to 140,118 by 2032. The history of Kisii Town may be traced back to the pre-colonial times when a famous prophet called Sakawa had its vision (Munge et al, 2016). According to Ochieng (1974), Sakawa would regularly gather his admirers at the location where the town currently stands and thereafter foretell where the police station, hospital, professional offices and churches would be built in future. Looking at the present Kisii Town, it is believed that his prophecies came to fruition. According to Ontumbi (2014), Kisii Town has grown as an administrative and commercial centre since 1905 during the colonial rule. By then, it was a small trading centre when the British colonial government established an administrative centre for both Kisii and South Nyanza Districts. Kisii Town became an urban centre and district headquarters for Kisii District in 1963. In 1973, it was elevated to a town council status and its boundaries subsequently extended to cover 35 km2 and finally elevated to a municipal status in 1981. The status terminated in 2012 after the enactment of the Urban Areas and Cities Act of 2012, whose sections nine (9) and ten (10) respectively relegated it to a town status on the account of not meeting the population threshold of 250,000. The current physical development plan for Kisii Town that was prepared in 1972 covered four (4) km2 of the town’s area of 35 km2. Though it has not been revised, so far, it remains as the only legal document for undertaking land use planning and enforcing development control by the County Government of Kisii (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Location of the study area (Source: Omollo, et al. 2018) |

2.2. Target Population and Key Informants

- A target population is that population, which the researcher wants to generalize results (Mugenda & Mugenda, 2003). It also refers to all items in any field of inquiry (Kothari, 2004) or the total collection of elements about which one wants to make inferences (Cooper & Schindler, 2008). In the present study, all items of inquiry, thus target population, included 106 professional staff from the nine (9) departments of the County Government of Kisii who were directly involved in land use planning and administration, and 25 practising land surveyors. Each of the identified categories of target population were separately examined as case studies after which collected data was jointly analysed to address the research objective. Yin (2009) justified that such an approach for case studies is permitted when multiple sources of evidence is required in research. County Government professional staff were targeted to investigate the extent of co-ordination and collaboration, a choice supported by section 32 (2) of the Physical Planning Act (Cap 286) which requires planning authority, when considering a development application submitted to it, to coordinate and collaborate with other authorities. Since such authorities or officers as stakeholders play a crucial role in land use planning preparation and implementation, they were better placed to comprehend the underlying issues in land use coordination and collaboration. On their part, registered land surveyors plays a fundamental role in land subdivision process. In this way, they provided crucial information as regards the extent to which land subdivisions were procedurally processed and coordinated in the study area. Besides the identified target population, individual key informants were also used to obtain information on the extent of co-ordination and collaboration of land use planning. As units of observation, they included, National Construction Authority (NCA) Coordinator; County Director of Physical Planning and Urban Development (CDPPUD); County Surveyor (CS); County Director of Environment (CDE); County Public Health Officer (CPHO); County Lands Registrar (CLR); Coordinator, Kenya Forest Service (KFS); Director, Energy, Water, Environment, and Natural Resources (EWENR); Director, Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperative Development (ALFCD); Director, Roads, Public Works and Transport (RPWT); Director, Gusii Water and Sewerage Company (GUWASCO) and National Land Commission (NLC) Coordinator.

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Design

2.3.1. Sample Size

- As suggested by Saunders et al (2003), the choice of sample size in this study was determined by the confidence level, the margin of error and the total size of the population from which the sample was drawn. Selection of sample size for the targeted County Government of Kisii professional staff was guided by the Sample Size Determination Table as recommended by Krejcie and Morgan (1970). According to Krejcie and Morgan, if the population (N) = 106, the sample size (S) should be 80. On their part, Martinez-Mesa et al (2016) recommended studying of the entire population if the size of the population is small and has a particular set of characteristics of interest. In the current study, the records maintained at the County Survey Office indicated that Kisii Town had 25 practicing land surveyors. As advised by Martinez-Mesa et al., the entire population was examined to determine if they were complying with land subdivision regulations as per the Physical Planning Act (Cap 286).

2.3.2. Sampling Design

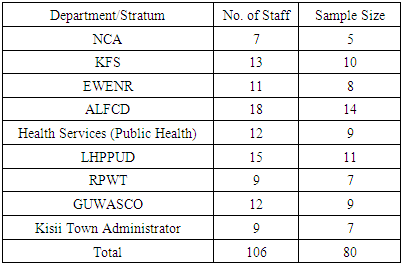

- The nine departments of the County Government formed the strata used for sampling. A list of their professional staff was thereafter obtained from respective heads of departments and compiled to constitute a sampling frame. To get a representative and proportional sample proportion for each stratum, the number of staff from each of them was divided by the total number of staff (106) and the product subsequently multiplied by desired sample size of 80 (Table 1). Saunders et al. (2003) justified that use of random numbers enables selection of samples without bias. A simple random sampling technique using the Random Number Table was for that reason used to select the number of staff from each department/stratum to participate in the study.

|

2.4. Data Collection

- Primary data was collected using questionnaires having both structured and unstructured questions. Questionnaires were self-completed, implying that after they were physically delivered to respondents, they were collected at a later date that was convenient for them. It took an average of three weeks to collect all the self-administered questionnaires from these key informants. Secondary data was also collected by reviewing various documentation maintained by relevant county government offices.

2.5. Reliability, Validity and Pilot Testing

- The current study used content validity which Kothari (2004) defined as the extent to which a measuring instrument provides adequate coverage of the subject under investigation. If the instrument has a representative sample of the universe, the content validity is good. However, for it to be effective, Yaghmaie (2003) recommended that two expert judgments are necessary. In order to conform to this important requisite, all questionnaires were given to two professors in urban and regional planning. In this case, one assessed what concepts the instruments were trying to measure, while the other determined whether the items or checklist adequately represented the concept under study. Instruments were finally improved by reviewing on the basis of the professors’ recommendations as well as the pilot test To test for reliability, the study adopted Cronbach Alpha to measure internal consistency. Baker (1994) recommended that a minimum 10% of the main sample size is an acceptable number for undertaking any pilot study. Applied to the current study, this included eight (8) for County Government professional staff; and three (3) for practicing land surveyors. Caution was taken to ensure that pilot study respondents were selected outside the main study sample, but from within the target populations with matching characteristics. In this case, pilot testing was conducted in Nyamira Town, 25 km from Kisii Town.

3. Findings and Discussions

3.1. Response Rates and Results of Pilot Study

- Mugenda and Mugenda (2003) recommended that whereas a response rate of 50% is considered as adequate for data analysis and reporting, 60% is good and 70% and above excellent. In the current study, the response rate for professional staff was 81.25% and that of practising land surveyors was 83%. These were adequately representative for drawing conclusions in addition to making recommendations towards effective strategy for co-ordination and collaboration in land use planning framework in Kisii Town. According to Kothari (2004), results of pilot study should always be reported in research. Cronbach’s α for the questionnaires were 0.084 and 0.720 for professional staff and practising land surveyors respectively, which showed very high levels of internal consistency.

3.2. Extent of Collaboration in Land Use Planning

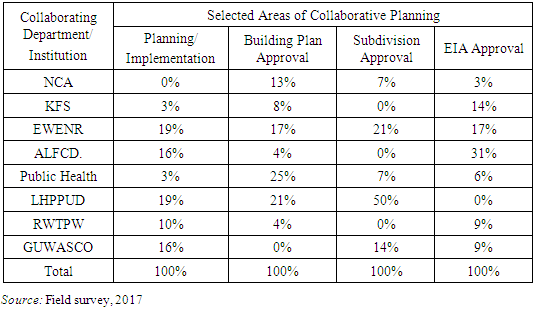

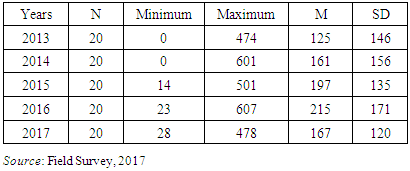

- As a concept, collaboration refers to the common engagement of participants in a harmonised effort towards solving a problem together. Collaborative interactions are generally characterized by shared goals, symmetry of structure, and a high degree of negotiation, interactivity, and interdependence (Lai, 2011). Extent of collaboration was examined in the context of section 32 (2) of the Physical Planning Act (Cap 286) which requires the CDPPUD, when considering development applications, to consult with other government departments. In the current study, collaboration was therefore construed to entail a process where different stakeholder departments came together in building and promoting a cohesive vision as relates to preparation and implementation of development plans, approval of building plans, approval of subdivision plans and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Extent of stakeholder departments’ participation in these selected collaborative planning areas which are facilitated by CDPPUD and National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) is summarised (Table 2).

|

|

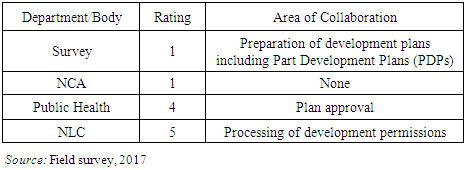

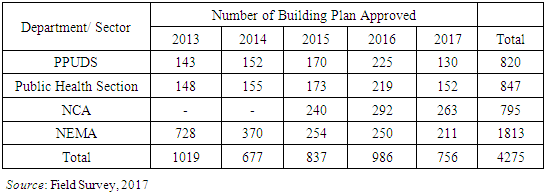

3.3. Extent of Co-ordination in Land Use Planning

- Unlike collaboration which entails two or more institutions working together to achieve a common goal, co-ordination begins with an assumption of differences. Different units create overlap, redundancy and/or separation without co-ordination (Lai, 2011). In the present study, the purpose of co-ordination was envisioned to ensure that various actors or agencies whose technical scope covered land use planning (such as NCA, NEMA, Survey) were centrally organised by PPUDS to enable them work together effectively and efficiently. An examination of co-ordination on land use planning commenced by testing the assumed relationship between the current co-ordination framework and attainment of development control objectives. Descriptive statistics were derived from questionnaires administered to sampled professional staff using a five point Likert scale (1 to 5) as the case of previous analyses. Results averred that as regards co-ordination, corresponding value on the Likert scale was ‘moderate’ (M = 2.74; SD = .871). The same applied to attainment of development control objectives (M = 2.69; SD = .88). Pearson's bivariate correlation further showed a significant positive relationship between the two variables (r = .585, N = 65, P =.000) suggesting that ineffective co-ordination negated realization of development control objectives, thus providing room for unplanned land use change. Having established occurrence of a statistically significant positive correlation between the two variables, the study further investigated the extent at which selected key aspects of land use planning, namely, land subdivisions and building plan approval, were centrally coordinated in Kisii Town under the guidance of CDPPUD.

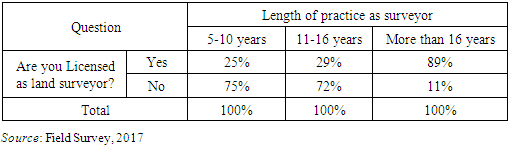

3.3.1. Land Subdivisions

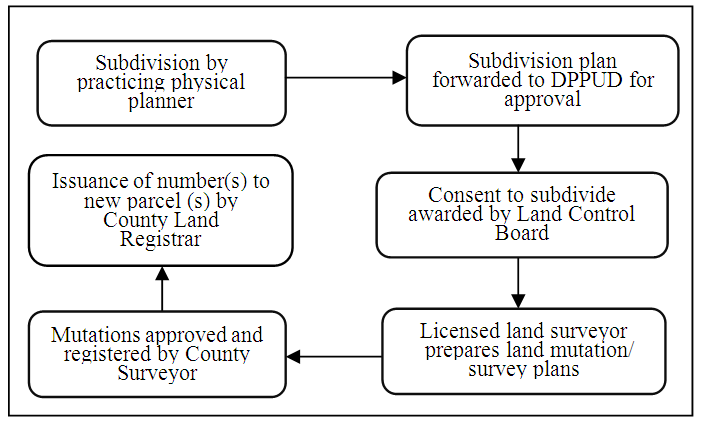

- The first stage in approving land subdivisions is preparation of subdivision plans by registered and practising physical planners in accordance with section 21 of the Physical Planners Registration Act (Cap. 536). The subdivision plan is afterwards submitted to CDPPUD accompanied by Form PPA1 and approval later issued through Form PPA2 if all planning conditions are fulfilled (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Land subdivision development control process in Kisii Town (Source: Kisii County Physical Planning Office, 2017) |

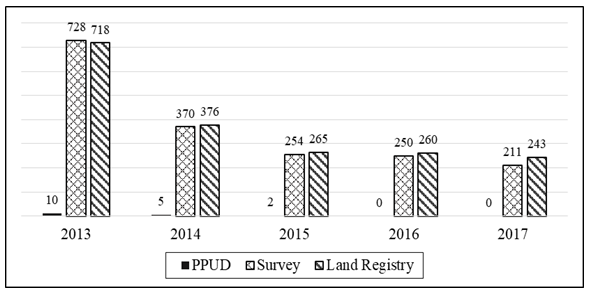

| Figure 3. Frequencies in processing land subdivisions (Source: County Survey Office, PPUDS and County Land Registry, 2017) |

|

|

|

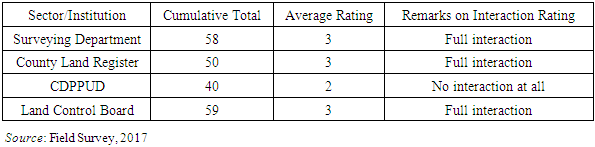

3.3.2. Approval of Building Plans

- The study furthermore investigated the extent at which key departments (CDPPUD, Public Health Section, NCA and NEMA) interacted while approving building plans as required by their relevant statutory guidelines. While PPUDS and Public Health Section operates under the Physical Planning Act (Cap 286) and Public Health Act (Cap. 242) respectively, NCA and NEMA on the other hand are respectively guided by the NCA Act (2012) and Environmental Management and Co-irdination Act (EMCA) (1999). Since these institutions envisage a sustainable built urban environment, their trends in building plan approval process between 2013 and 2017 was compared (Table 7).

|

4. Conclusions

- Although sustainable urbanisation has been entrenched by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as one of 17 global goals that make up the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and that an integrated approach to planning is crucial for progress, this is not the case in Kisii Town where co-ordination and collaboration in handling of crucial aspects of land use planning and development control processes remains a mirage regardless of the existing statutory framework. This has contributed to a multiplicity of problems such as weak enforcement of relevant laws, regulations and physical planning standards that are used in the enforcement of development control. Further, owing to the observed administrative gaps in land use planning, the beneficiaries continues being developers and practitioners, especially land surveyors, who occasions unregulated land use change as they are constantly ahead of planning authorities. These problems are expected to escalate in a near future because as demonstrated in Figure 1, the current physical development plan for Kisii Town covers only 4km2 of the town’s area of 35 km2, revealing that 87.5% of the town remains unplanned. With the prevalling status of affairs, there is a dire need for an incusive strategic co-ordination and collaboration framework in Kisii Town. These aspects should be considered as tenets in land use planning since they provide the basic means by which various agencies and government departments intercedes to regulate use and development of land use in order to implement local and national planning policies. Moreover, they aim to safeguard that patterns and nature of proposed developments conform to policies set out in physical development plans. This precautions that environmental challenges emanating from land use conflicts can be reduced to acceptable levels, leading to orderly land use that supports sustainable development. From the study findings, the following recommendations are suggested towards a more comprehensive collaboration and co-ordination framework in Kisii Town:i) The County Government should establish a County Spatial Planning Coordinating Committee (CSPCC) to harmonize and coordinate the institutions and related agencies that deal with development control process and management. CSPCC membership should consist of:a) Chief Officer responsible for physical planning who shall be the Chairperson; b) CDPPUD who shall be the Secretary;c) Officers heading the following key County Government departments: Survey and Mapping; Lands (Registry); Public Health; NEMA; Agriculture; Roads and Transport; GUWASCO, NLC and NCA; andd) A registered physical planner; land surveyor, EIA expert and architect in private practice and who are in good professional standing, duly appointed by the County Government.The functions of the Coordinating Committee shall include, but not limited to:a) Vetting and recommending development applications;b) Ensuring that physical planning and development control activities in the county are efficiently carried out without any conflicts or overlaps among various implementing government agencies;c) Formulating policies to guide development applications;d) Coordinating implementation of approved physical development plans; e) Ensuring compliance in development on accordance to the approved plans and zoning regulations; andf) Enquiring into and determining conflicting claims or appeals made in respect of applications for development permission.ii) In order to ensure that only registered professionals undertakes consultancy on development control, CDPPUD should form a collaborative partnership with relevant professional associations as well as Boards that regulate professional practice (such as Physical Planners Registration Board – PPRB; BORAQS; Engineers Registration Board of Kenya – ERB; and Land Surveyors Registration Board). CDPPUD should therefore ensure only statutorily registered persons are involved in development control process. It should hence implement a more rigorous mechanisms for detection of frauds in the preparation of development proposals including implementation and supervision of these proposals. iii) Adiitionally, CDPPUD should be incorporated as a full member of all Land Control Boards in Kisii County as per part 1 (a) (b) of the First Schedule of the Land Control Act (Cap. 302) to offered advisory opinion on development control processes which have implications on land subdivisions. iv) Finally, a comprehensive physical development plan that covers the entire town should be urgently prepared to provide a framework for spatial planning and development control.This study has therefore added to the existing body of knowledge in physical planning by demonstrating the implications of ineffective collaboration and co-ordination in land use planning and development control.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML