-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2018; 8(2): 59-67

doi:10.5923/j.re.20180802.06

Sustainable Forest Planning: (Case Study Production Forest in Banten Province)

Risman Pasaribu1, Abdul Hakim2, Bagyo Yanuwiadi2, Aminudin Afandhi2

1Student of Doctoral Program of Environmental Science, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

2Lecturer of Doctoral Program of Environmental Science, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Increased land conversion across forests so that a new paradigm is needed in planning for sustainable forest management. The purpose of this research is to recognize the forest planning pattern applied in and outside the HPH (Hak Pengusahaan Hutan, Forest Concession) in the forest area in the forest management unit. The data of this research is using quantitative and qualitative descriptive research and this research is conducted in one and half year in Banten Province. The results of in-depth interviews related to current forest management planning, 74% of respondents agree that the boxgrid system becomes less suitable to be applied because of all secondary forest. 100% of respondents agreed that the DAS-based pattern is more suitable to be applied in Banten Province from the results of GIS and AHP special analysis, gained mathematical equation of a special submodel of potential conflicts (MSPK), that is MSPK = (0.473xsPL) + (0.2521xsKJ) + (0, 11430xsJP) + (0.0850xcKTL) + (0.0466xsKTL) + (0.0466xsKL). From this equation, the area percentage of the highly conflicting area to adequate conflicting area reaching 71.4% and 29.6% is slightly conflicting to safe. Meanwhile, at a distance of 500 meters from the edge of the area, the percentage of conflicting areas reached 53.8% validation of this equation is done through the identification of potential conflicts such as socio-economic aspects, that is exist the potential for conflict of forests reaches 45%, based on special biophysical studies, the potencial of very conflicting area reached 69%, conflicting 15.4%, adequate conflicting 44.9%, slightly conflicting 28.8%, and 5% almost without conflict. The result of GIS and AHP special analysis obtained by the submodel of priority location of land rehabilitation (MLPR) is MLPR = (0,3769xspl) + (0,3699xskl) + (0,1615skj) + (0,0917xsfh). From this equation obtained area that can becomes first priority scale for reforestation (with clear cut), that is 2,1%, second priority (reforestation without clear cutting) of 12%, third priority (reforestation without clear cut and building a conservation building) of 31.3%, fourth priority (enrichment and selective development) that is 39.7%, fifth priority (enrichment and intensive silviculture) of 9.9%. From GIS analysis obtained units as analysis unit which also called plot will be combined with above submodel equation. The effective and efficient area of the unit is between 50-100 hectares. In this study, the number of units or plots that formed are 103 plots and 536 of plot pieces. The plot and the plot pieces are numbered clockwise. All rooms are given code number with order by Province, forest section, KPH, DAS and plot.

Keywords: Planning, Sustainable Forests and Sustanable Development

Cite this paper: Risman Pasaribu, Abdul Hakim, Bagyo Yanuwiadi, Aminudin Afandhi, Sustainable Forest Planning: (Case Study Production Forest in Banten Province), Resources and Environment, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2018, pp. 59-67. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20180802.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Deforestation is a change in land closure conditions from forests to non-forests (including changes in forest land use for plantations, settlements, industrial estates and others). The Ministry of Forestry (2012) states that based on the results of LANDSAT ETM 7+ satellite image interpretations, observation of 2005/2006 and 2009/2010 the space of deforestation in and outside forest areas throughout Indonesia reaches 610,376 ha / year and 221,751 ha / year or 832,128 ha / year. But lastly, Forestry Minister Zulkifli Hasan said that at the time of reform, the extent of forest destruction in Indonesia reached 3.5 million ha / year, but then the nominal of that condition decreased to 300,000 ha / year. This damage, are more caused by the result of illegal logging (Republika.co.id, 2012). The factors that cause deforestation and land degradation are complex and covers many aspects. There are two factors that cause deforestation, which are direct and indirect factors. The immediate causes are logging, unlicensed logging, and forest fires that are not difficult to control and often occur, especially during long dry seasons. Market failure and policy failure as an indirect cause of deforestation. Market failure, such as, too low the wood price from specified. And, the failure of the policy is, the long period of exploitation in forestry but not become incentives to doing cultivation and / or enrichment, and other issues are socio-economic and political (CIFOR, 2008). Analysis of the deforestation patterns of 152 countries, there are 3 main sources of deforestation: agricultural expansion, forest timber exploitation and infrastructure development. These interacts with five main contributing factors: demography, macroeconomics, technology, policy (governance) and culture (Geist and Lambin, 2002); (Kanninen et al., 2009). None or weak management planning is indicated by the absence of site-level managers (Karsudi, et al, 2010). Furthermore, BAPPENAS, (2011), suggests that based on fishbone analysis can be identified some of the major causes of deforestation and degradation: weak spatial planning, ineffective forest management units, weak governance, tenure issues and legal basis and weak law enforcement. Forest planning has not been considered a baseline in sustainable forest management. This can be caused by many things, among which the main is the availability of accurate spatial databases of forest areas that are not yet widely available and human resources that have not understood the design of sustainable forest management at the application level with the resolution of macro and micro studies, so that not many sustainable forest planning has been formed (Sirang & Jauhari, 2008). Only 14% of projects have a base map of their territory (CIFOR, 2008).The old pattern of yield setting is to relate the volume per hectare per plant age to the area. In practice in the vast field of work plots per year is the area divided by age rotation, which is 100 ha / year or 25 ha / year. This pattern is only based on wood production has not been concerned about social and environmental aspects (Davis, 1970). The forest planning pattern of the forest concession is still largely using the old pattern known as the 'annual coupe' or the chessboard pattern in Indonesia (Basari & Dulsalam, 2012).Another fact is that currently the forestry service is more as a forestry administrator, the forest management process is not done. This requires changes, especially starting from forest planning. The Ministry of Forestry has issued the concept of Forest Management Units (KPH, Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan) as mandated in PP No.6 / 2007 Jo.P3 / 2008 on Forest Management, Preparation of Forest Management Plans and Forest Utilization.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Forest Planning

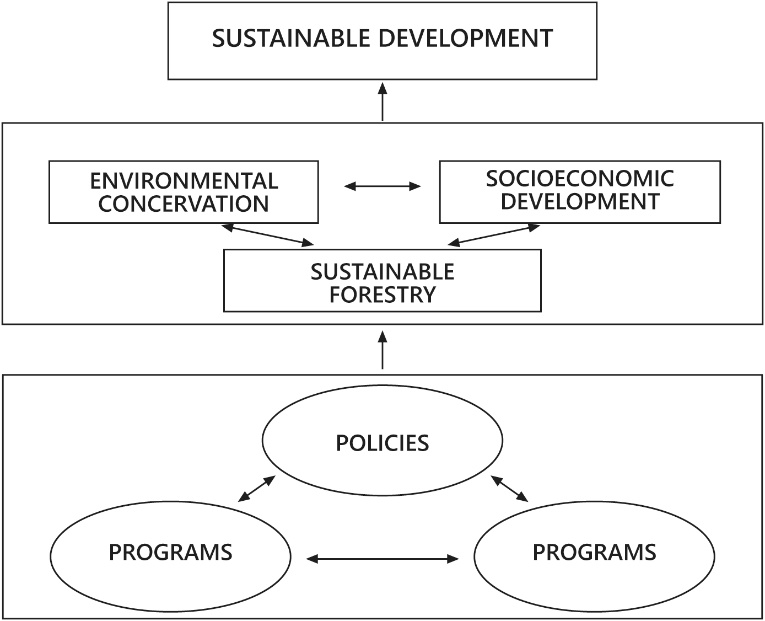

- Forestry planning is "the process of goal setting, the determination of the activities and tools necessary for sustainable forest management to provide guidance and direction to ensure the achievement of the goal of forestry to the greatest extent possible for the just and sustainable prosperity of the people" (PP 44/2004).Evaluation is the assessment / analysis of the success rate of forest planning activities from planned planning. Evaluation activities are carried out periodically, that is: (a). Evaluation at the beginning of the activity, undertaken to assess preparation / planning of forest planning activities, (b). Annual Evaluation, conducted to assess the results of activities that have been achieved during one year of forest planning activities, based on monitoring results and (c). Five Yearly Evaluation, conducted to assess the overall success rate of the forest planning program, from the beginning of the activities to the end of the activity, based on monitoring results.The principles of forest planning are the use of sustainable ecosystem resources, comprehensive, ecosystem-based, landscape perspectives, multicriteria objectives, alignment, participatory, adaptive, logical assessment, knowledge + emotion + moral decision-makers, prevention and care, and monitoring (Gadow et al, 2000, in Malamassam, 2009). Hahn and Knoke (2010) describes that Sustainable Forest Management has interdisciplinary but sectoral characteristics, characterized by heterogeneity, less hierarchical, more transparent and complex, socially accountable and more reflexive than Conventional Forest Management (CFM), short-term - long-term perspective, participatory process for determining definitions of criteria and indicators.The basic concept of forest planning is to integrate social, economic and environmental aspects in order to utilize the greatest possible outcome of the forest for the economic interests of the company (large or small scale) and the community around forest while maintaining the limits of the dynamic capacity of the production forest resources (Malamassam, 2009). In principle, the concept of Sustainable Forest Management (PHL, Pengelolaan Hutan Lestari) has three types: (1). The sustainability of forest products, this type focuses on the same annual or periodic timber yields. To realize this sustainability type, arise various concepts of silviculture systems, rotation determination, proper logging techniques and so on, (2). Sustainability of potential forest products. Sustainability of forest product potentials oriented of forest as timber mills. Forest managers have the opportunity to maximize the productivity of forest areas not only by producing conventional products to maximize profits and (3). Sustainability of forest resources. The sustainability of forest resources focuses on forests as timber and non-timber ecosystems, water and soil fertility protectors, environmental preservers, and serves as a warehouse for the survival of a wide variety of genetic resources, both flora and fauna (Nurtjahjawilasa et al. 2013).Sustainable Forest Management covers ecological, economic and social aspects explicitly and thus goes beyond the meaning of the multi-function effect of wood production. It is recognized that there is a conflict potential between land users, land use forms and other social interests (Wolfslehner, 2007). Population, economic and political pressures have contributed to the exploitation of natural resources and land degradation including forestry (Khususiyah, 2013). Ministry of Forestry through PP no 6/2007 Jo. P3 / 2008 undertakes the Development of Forest Management Unit (KPH, Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan) program to be implemented throughout Indonesia. The KPH program is echoed with a vision of sustainable forest development, with social, economic and environmental aspects being the main pillars supported by institutional aspects (Karsudi et al., 2010).

2.2. Forest Evaluation

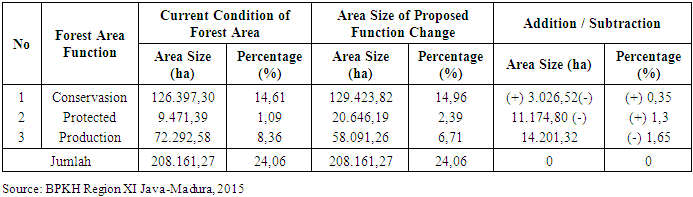

- Forest Management is an activity to build a forest management unit, including the grouping of forest resources according to the type of ecosystem and the potential contained therein in order to gain the maximum benefit for the community in a sustainable manner. Forest and land governance refers to processes, mechanisms, rules and institutions to decide how land and forests are managed. Governance mechanisms may be of formal legal, regulations, or government program to regulate land and forest use, such as those undertaken by communities or informal monitoring schemes that determine how forests, lands and natural resources are utilized.Forestry potency in Banten Province other than Forest Area (State Forest) also have Forest of Ulayat Right and Forest of People. Production forest area in Banten Province is divided into several classes of company which is company class Teak 34.759,15 Ha, company class Mahogany 14,844,44 Ha, and company class Acacia mangium 22.179,19 Ha. Beside have forest area mentioned above, Banten Province also have special conservation area of Baduy covering 5,136.58 Ha based on Lebak District Regulation No. 32 Year 2001 About Protection of Communal Rights of Baduy Society. Management of production forest areas in Banten Province is directed to the utilization of forest products by taking into account the principles of forest sustainability. Location of production forest area are spread out in 3 (three) districts of Lebak Regency, covering Banjarsari, Cileles, Gunung Kencana, Bojong Manik, Cikulur and Cimarga; Pandeglang Regency, covering Cikeusik, Munjul, Cibaliung, Mandalawangi, Labuan and Cimanggu; and Serang Regency covering Mancak and Ciomas. In addition to state forest area, the indicative area of community forest in Banten Province reaches 322.152.59 ha with the potential of wood / stands reach 9,011,156,44 m3 and carbon potential reach 5,152,034,71 tons. The people's forest in Banten Province that have the largest area is in Lebak Regency followed by Pandeglang regency. The dominant people’s forest plantations in Banten Province are sengon, durian, tangkil, teak, and mahogany.According to Law No. 23/2000 on the Establishment of Banten Province, the total area of Banten Province covers 865,120 ha, while the area of state forest barely reaches 208,161.27 ha. When referring to Law Number 41 Year 1999 regarding Forestry and Law Number 26 Year 2007 on Spatial Planning, the proportion of forest area is at least 30% of the total Watershed area but in fact the proportion of forest area in Banten Province reaches only 24 , 06%. However, with the presence of community forest outside the forest area, the total land cover in Banten province is still larger than the forest area. The KPH has the duties and functions of organizing forest management. One such task and function is forest governance and forest management plan (Government Regulation Number 6 Year 2007). Technical guidelines for the preparation of forest arrangements and the preparation of management plans regulated in PerdirJen Planologi no. P.5 / VII-WP3H / 2012.

2.3. Sustainable Forest and Sustainable Development

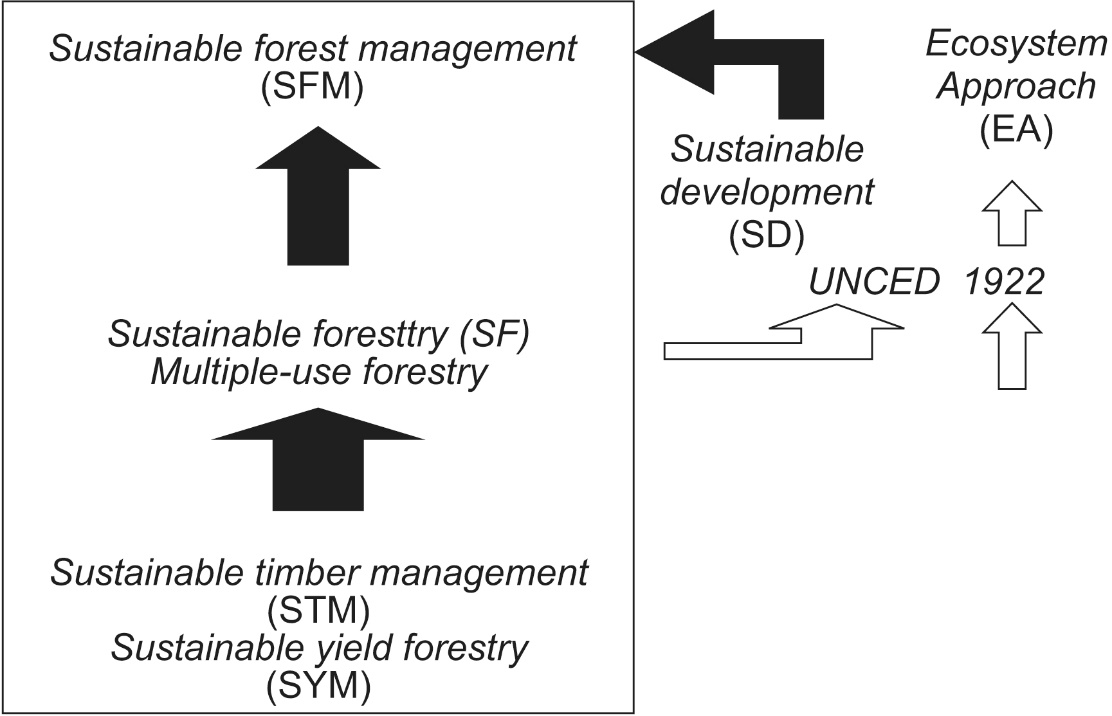

- CIFOR (2007) argues that the main goal of sustainable development is to promote the use of the environment and resources to meet the needs of today's society without sacrificing the future. The World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987 in Atkinson et al. (2007) says that some authors cite the well-known definition of the Brundtland Report that sustainable development is a 'development that meets the needs of today's generations without sacrificing the ability of future generations to meet their own needs'. The essence of each definition is about how development outcomes are shared across generations.According to Clark (1976); Christensen (in Atkinson et al., 2007) the words 'Sustainability' and 'sustainable development' are often used interchangeably in the field of academic research and policymakers. However, it is different, and should be clearly defined and used with caution. To maintain the activity or process for the system to run for a long time, the environmental economics and ecological resources is a renewable resource that potentially can be used indefinitely. The term "sustain" (Moffat, 1995 in Bruckmeier, 2009) is often used in the context of maximum results that sustainable, has been used to understand and contribute to resource policies in the field such as forestry and fisheries management. According to WCED (in Atkinson ef a /., 2007), sustainable development is a broader concept than sustainability and emphasizes both the idea of sustaining long-term activity for present and future generations and linking such activities to development rather than economic growth. According to Daly, 1972 in Atkinson et al., 2007) that you will not be able to have economic growth and resource consumption continously and pollution that occurs on earth with biophysical potential and limited assimilation process.The main goal of sustainable development is to promote the use of the environment and resources to meet the needs of today's society without sacrificing the future (Adger, 2000). Sustainable development is 'development to meet the needs of current generations without sacrificing the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Atkinson et al., 2007). There are two meanings within it; The first is the "needs" and "limitations". The needs is the main need for human to continue life, while the limitations are the environment and natural resources to be able to meet human needs (Adger, 2000). In the framework of sustainable development of Law No. 32 Year 2009 on Environmental Protection and Management article 7, paragraph 2 stipulates that there are 8 (eight) considerations for the determination of ekoregion. These considerations are: characteristics of landscapes, watersheds, climate, flora and fauna, socio-cultural, economic, community institutions and environmental inventory results.The environmental concept used is 'High Conservation Value Forest (HCVF)'. The concept of High Conservation Value Forest has emerged since 1999, as a 'principle 9' of sustainable forest management standards undertaken by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). From the revision of the first Indonesian HCVF Toolkit (2003), revised HCV guides recommends 6 HCVs, covering 13 sub-values. The thirteen sub-values are broadly grouped into three categories, which are: (a). Biodiversity-HCV 1, 2, and 3, (b). Environmental Services-HCV 4, (c). Socio-Economic Culture-NKKT 5 and 6 (Jennings et al., 2003); (Revision Consortium of HCV Toolki Indonesia, 2008). Furthermore, Jennings et al. (2003) that the concept of HCVF is designed with the aim of assisting forest management particularly improving the sustainability of social and environmental aspects associated with timber production activities. This requires a two-stage approach, as follows: 1) identifying areas within or near the Management Unit (MU) that have significant social, cultural and / or ecological values, and 2) management systems that can supports maintenance and / or improvement of those values.The basic principle and concept of HCVF is the areas where found attributes that has high conservation value are not necessarily becomes areas where development is not allowed. The HCVF concept requires that development is undertaken in a manner that ensures maintenance and / or upgrading of existing HCVFs. Thus, HCV helps the community toward a rational balance between sustainable living and long-term economic development (Consortium for Revision of HCV Toolki Indonesia, 2008).Hahn and Knoke (2010) for free stages of development of forest management in the world as presented in Figure 1 below. Sustainable Forest management has interdisciplinary but sectoral characteristics, characterized by heterogeneity, less hierarchical, more transparent and complex, more socially accountable and more reflexive than Conventional Forest Management (CFM), short-long term perspective, participatory process for defining criteria and indicators.

| Figure 1. Forest Sustainability Hierarchy (Source: Hahn and Knoke, 2010). Caption: The size of the arrow represents a qualitative impact on the stages of development of sustainable forest management |

| Figure 2. Sustainable Forest Management Model Framework (Source: Rebugio and Camacho, 2003) |

3. Research Method

- Research was conducted in Banten Province. This location was chosen because the conservative forest in Banten Province reached 72,292.58 ha or 34.73% of the forest area in Banten Province. The area of conservation forest in Banten Province reached 171,454.30 ha or 60.72% of the forest area (mainland) in Banten Province. Observation method used in this research as follows:

3.1. Observation of Flora

- The method used was the Stratified Sampling with Random Start. Survey paths are cut into contours. The sampling intensity used is 0.2% of the raster area having a NDVI value of 0.4 or above or NDVI 6 and 7 classes or areas considered to be forest covering 4,239.5 ha (NDVI calculation results). So the required sample area is 8.4 ha.

3.2. Observation of Fauna

- The method of observing wildlife species is Rapid Assessment Method. This animal observation is conducted not only on the same survey path as the observation of timber potential, but also goes beyond observation time and based on community information. Parameters recorded were the types of animals found and the position of the plots as they were found and locations based on community information. This method cannot be used to calculate the population.

3.3. Observation of Environment

- Observation on environmental aspect is observation. The observation location for a conservation area is a location that has a high degree of accessibility and is sufficiently representative of all existing conservation areas. Locations observed such as tributaries and springs.

3.4. Socio-Cultural-Economic Survey

- The method for Social-Cultural-Economic observation is the survey method. The socio-cultural-economic parameter taken is the potential for disturbance to the forest. This parameter was measured through in-depth interviews with key figures in the community and field observations. Key villagers in each village are determined purposively according to forestry-related needs, such as village heads, community leaders, religious leaders, heads of farmer groups. Number of informants in each village are determined as much as 2-3 people. While the total villages in the Tabunio watershed and located near / within the forest area are 19 villages. Out of these 19 villages, 12 villages are chosen that have wide and accessible areas, so that the total of informants needed is 37 people.

3.5. Survey of Perceptions on Sustainable Forest Planning

- The method for the perceptual aspect of sustainable forest management in forest concessions is the survey method. The aspects observed are aspects of forest planning related to Sustainable Production Forest Management (PHPL, Pengelolaan Hutan Produksi Lestari) assessment documents, use of chessboard patterns and watershed patterns. This aspect becomes the subject of in-depth discussion / interview with forestry experts from Higher Education, Department / Forest Service and Independent Appraisal Agency.

3.6. Equipments Used

- The tools used in this research include garmin 76CSx GPS, general thematic maps (roads, rivers, administrative boundaries), ALOS imagery, LANDSAT-8, Binoculars, Cameras, stationery and a set of questionnaires for in-depth interviews on land recognition and community perceptions of forests, the perceptions of forest experts on sustainable forest planning and expert judgment questionnaires on land conflicts and production / rehabilitation priorities.Analytical methods used for biogeophysical areas include: Watershed analysis, Terrain Analysis, Geoprocessing analysis (buffer, intersect, and others), NDVI analysis (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index). Meanwhile, for the socio-economic-cultural field, a qualitative descriptive analysis is used. The socio-economic-cultural parameters taken are the ownership / recognition of land within the forest area by the community surrounding the forest and the community's perception of the forest. Parameter of land ownership is taken / determined through result of interpretation of satellite image especially for land use and people perception through in-depth interview and field observation. The analysis of raster data was undertaken to make forest planning decisions related to the multi-faceted aspects of the forest planning activities that studied. This analysis is combining parameters through MCDM method (Multi Criteria Decision Making) or decision making, that is Analytical Hirarchi Process (AHP). The location of this research can be seen from the following map:

| Figure 3. Map of Research Location |

4. Research Result

4.1. Implementation of Forest Management

- Forest management policy in Banten Province has been regulated by Banten Provincial Regulation No. 41 of 2002 concerning Forest Management, written in Lembaran Daerah Provinsi Banten Year 2004 Number 69 Series E. Forest management activities as regulated in by Perda No. 41 of 2002 on Forest Management covers forestry planning activities, forest management, research and development, education and training, forestry counseling, and supervision. Until now, that regulation is the only legal basis in managing forest resources in Banten Province. To see the implementation of the policy in forest development practice, it is necessary to analyze the condition of forestry data in Banten Province which includes: (a). The expansion of the area closure covered by forested land in Banten province; (b). Condition of forest ecosystem and forest security disturbance in Banten Province; (c). Production of forest products including timber, non-timber forest products (NTFPs), and environmental services in Banten Province; (d). The existence of conservation forests for water and soil protection in Banten Province; (e). Biodiversity in forests in Banten Province; (f). Contribution of forestry activities to regional development in Banten Province; and (g). The existence of customary forests and community forestry development programs in Banten Province.

4.2. Development of Area and Percentage of Forests at Provincial Level, Both Forest and Community Forest Areas

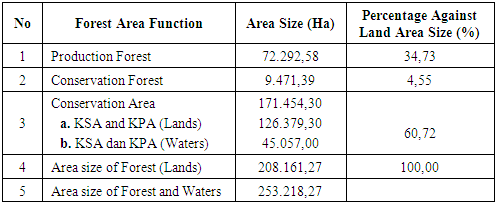

- The forest area in Banten Province is presented in table 1 which explains that the percentage of conservation forest area in Banten Province reaches 60.72%, production forest reaches 34.73% and protected forest reaches 4.5%. The extent of conservation forest areas in Banten Province indicates that the province has unique and distinctive forest resource potential as an ecosystem of various flora and fauna species, environmental service providers, and ecosystem protection.

|

|

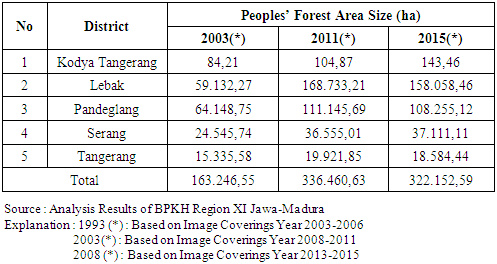

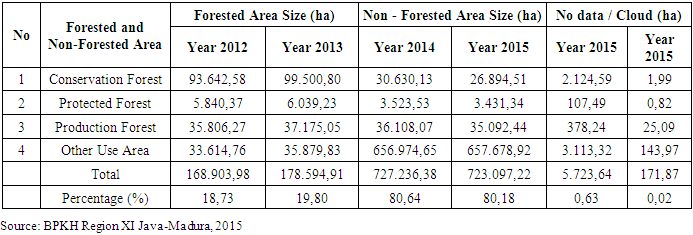

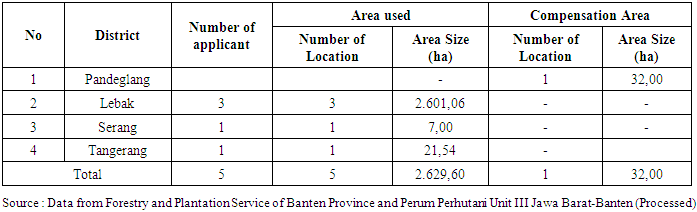

4.3. The Development of Wetland Closure Area in Banten Province

- Land covering conditions are very dynamic and rapidly changing which tend to open. BPKH Region XI Java-Madura (2015) conducted an analysis of land cover change in Banten Province based on the interpretation result of Landsat 7 ETM + Image coverage of 2005/2006 as follows: (a). Forested areas: 168,903.98 ha (18.73%), (b). Non-forested areas: 727,236.38 ha (80.64%) and (c). Incomplete data: 5,723.64 ha (0.63%). Particularly within the forest area, the land covering conditions are as follows: (a). Forested areas: 135,289.21 ha (64.99%), (b). Non-forested areas: 70,261,73 ha (33,75%) and (c). Incomplete data: 2,610.33 ha (1.26%).Condition of land covering in Banten Province based on interpretation result of Landsat 7 ETM+ Image Year 2008/2009 is as follows: (a). Forested areas: 178,594.91 ha (19.80%), (b). Non-forested areas: 723.097,22 ha (80.18%) and (c). Incomplete data: 171.87 ha (0.02%). Particularly within the forest area, the land covering conditions are as follows: (a). Forested areas: 142,715.07 ha (68.56%), (b). Non-forested areas: 65,418.30 ha (31.43%) and (c). Incomplete data: 27.90 ha (0.01%).Changes in forested and non-forested covering in Banten Province 2012 and 2015 are presented in table 3 below.

|

|

|

4.4. Sustainable Forest Planning Model

- For a long time, the Indonesian government has maintained a government-driven development policy characterized by a centralistic and economic growth orientation, which then impacts on the degradation of tropical forests in all aspects. It appears that the government should abandon this old policy in terms of government-based forest management and economics into community-based forest management (Nurjaya, 2005).Decentralized forest management has developed worldwide, and participation has become an important element in achieving sustainable forest management. In 2001, Community-Based Forest Management (PHBM, Pengelolaan Hutan Berbasis Masyarakat) initiated by State Forestry Company (Perhutani) in Java, Indonesia, to manage state forests in cooperation with local communities. The findings indicate that PHBM contributes to the suppression of illegal logging, rural development, and economic improvement of local households. Has a high potential for sustainable management of state forests through a profit sharing system. However, to increase participants' satisfaction is still a major challenge. Therefore, flexible revisions to PHBM agreements including profit-sharing rates as functions and social and economic changes are essential for long-term collaborative forest management (Fujiwara et al., 2012). The implementation of the Community Forest Managing (Community Collaborative Forest Management or PHBM (Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat)) program is widely expected by communities to provide more equitable access to forest resources in Java. Perum Perhutani is a state-owned company that manages forests in Java that have begun to implement land-sharing processes and share the right to harvest non-timber forest products (Anonymous, 2006). In Indonesia, Ecosystem Restoration (RE, Restorasi Ekosistem) in Production Forest (HP, Hutan Produksi) is a new forest management model. This is because since 2014 there has been a government policy on restoration of ecosystems in production forests. Production forest management applying ecosystem restoration supports the restoration of natural forest conditions, especially in degraded areas (Hidayanto et al., 2012).Currently, all forest areas in Indonesia (excluding forests in Java Island) will be built under the concept of Forest Management Units (KPH, Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan). This KPH is grouped into KPHL (KPH Lindung) group if the area is dominated by Protection Forest, KPHP group (KPH Produksi) if the area is dominated by Production Forest and if the area is dominated by Nature Reserve and / or Wildlife Sanctuary then grouped into Conservation KPHK. All existing forest management planning models are required under the KPH management system. Thus, KPH is expected to be the 'blue print' of forest management in Indonesia (Department-Forestry, 2011).

5. Conclusions

- The results of the research that has been done have these following conclusions: (1). Regional Regulation No. 41 of 2002 in 2002 has not been able to answer the existing problems in Banten province, the Regional Regulation No. 41 of 2002 is also seen as not able to answer the wishes of the regions (Kabupaten) in which the districts particularly in focus on research (Lebak and Pandegelang) fully oversees that timber products is a contribution to regional revenue, local governments in both districts have not optimized non-timber products in forest areas in their respective areas so that damage can be clearly seen in both Akarsari and Mount Honje, also Mount Halimun Salak areas and Mount Kendeng area in Lebak District. (2). The need for production forest resources in the contribution of regional development is often very different and even conflicting with each other which can eventually lead to conflict between stakeholders in fighting for production forest resources and environmental issues. Broadly speaking, management conflict of production forest resources can be grouped into two, namely vertical conflict and horizontal conflict. Vertical conflict is a conflict involving communities around the forest with other parties deemed to have authority in the management of production forest resources. While the horizontal conflict that occurs is the conflict that occurs between groups within the community itself.The results also provide the following suggestions: As regards of the development of sustainable forest planning, as stipulated in regional regulations 41 of 2002 should be considered in the planning of production forest development in all of the management unit's active strategy, management of the region, institutional management, sustainable production forest management and considering interventions, identification and deliberation and principles of sustainable production forest management fidelity and management rules, management inputs.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML