-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2017; 7(1): 8-12

doi:10.5923/j.re.20170701.02

Farmers’ perceptions of Soil Degradation in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria

Saadatu U. Baba

Abantu for Development, Kaduna, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Saadatu U. Baba, Abantu for Development, Kaduna, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study examines farmers perceptions of soil degradation and fertility in two communities in the drylands of northern Nigeria. The study uses semi structured interviews and focus group discussions to explore farmers’ views on soil degradation. It finds that farmers perceived a decline in productivity of their soils. The overwhelming reason was due to a lack of sufficient inputs especially fertilisers, because of cost and availability. The study finds that farmers’ socio economic circumstances are a driver of perceptions, and government policy on increasing agricultural production must make the unavailability and cost of fertilisers one of its focal points, given the importance of smallholders in ensuring food security.

Keywords: Soil fertility, Soil degradation, Fertilisers, Perceptions, Northern Nigeria

Cite this paper: Saadatu U. Baba, Farmers’ perceptions of Soil Degradation in Rural Kano, Northern Nigeria, Resources and Environment, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 8-12. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20170701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Food security has emerged as one of the most pressing issues in international development and in the developing world, fuelled by fears about the impact of climate change on agriculture and its effect on crop yields. By the year 2050, global food demand is expected to increase by more than half above 2006 levels, driven by urbanisation, population and income growth [1]. Smallholder farmers have been described as the backbone of global food security [2]. This is particularly true in the developing world, and especially in Africa. Majority of people in the developing world depend on agriculture for livelihoods, and the success of small holder farmers is essential to fulfil food security needs. Soil fertility and degradation are important determinants of yields. Nutrient material, weathering and human management are the main factors that influence soil fertility [3], and soil degradation has been identified as a driver of rural poverty and natural resource degradation [4]. Soil fertility is an important constraint on agricultural production. At present, soil nutrient management is therefore an important and direct determinant of crop yields. This paper analyses farmers’ perceptions of changes to soil fertility and crop yield in 2 smallholder farming communities in rural Kano in northern Nigeria. It considers the factors which influence these perceptions including ecology and socioeconomic conditions.

1.1. Soil Fertility Management in the Kano Zone

- The Kano Close Settled Zone (KCSZ) is a region stretching 100km from metropolitan Kano in northern Nigeria [5] and supports populations of up to 350 people per square kilometre [6]. Annual rainfall varies from 400mm in the north of the zone to 800mm and more in the southernmost part (7), so the region is classified ecologically as drylands. Generally, it has a short wet season from June to September or October and a long dry season which usually lasts from October to May, but the length of the wet season diminishes northward. Soils are former dune sands and low in organic matter [8] (Mortimore, 1993). The landscape is dominated by rain fed cultivation with many distinctive trees. Fields are small, usually less than a hectare. Agricultural activity is largely restricted to the short, wet season and the vast majority of farmers are male. In northern Nigeria, manure locally known as taki is the main source of fertiliser, and thus the possession of livestock is crucial for maintaining soil fertility. The manure, mixed with compound refuse, provides the vital organic fertiliser known as taki that is the bedrock of smallholder agriculture in the region.Studies into the management of soil fertility on small holder farms have explained how farmers manage nutrient flows into farms and achieve sustainability through crop and livestock integration ([6, 9]) and the use and management of manure [10]. Some farmers manage soil fertility by combining crop planting patterns and application of farmyard manure and livestock corralling [10]. Other studies show that farmers’ perceptions regarding vegetation, and decline in soil fertility and crop yield suggested that population pressures and land use are negatively affecting environmental change [11]. A number of studies of soil nutrients in the KCSZ suggest that there is no empirical evidence of a drop in soil fertility ([8, 11, 12]). But farmers in these studies perceived a decline in the productivity of their soils. This disparity in scientific studies and local perceptions occur in other dryland regions of Africa as well ([13-15]). This may be because empirical studies of soil nutrients provide only a partial picture of soil fertility, and external and broader concerns affect farmers’ perceptions of their soils [11]. Changes in soil fertility therefore often are ‘nested within a variety of social, political and economic factors that clearly encourage or prohibit investment in the land’ [5, p103].

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

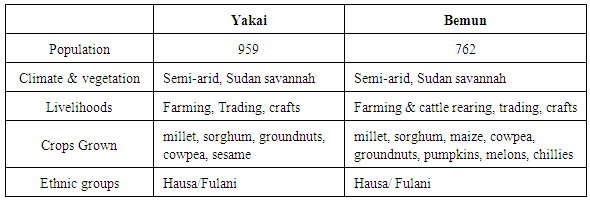

- The study sites are 2 communities in the KCSZ, Bemun & Yakai, and share many of the typical characteristics of the area. Both are classified as dryland communities, but Yakai is more arid with slightly less rainfall and vegetation. and Bemun has a longer wet season. As a result, there were some differences in main crops planted, dominant vegetation, and soil types, shown in “Table 1”.

|

2.2. Research Methods

- The fieldwork was carried out in 2011 and 2012 as part of a broader PhD research on land degradation. The aim of the research is a constructivist study of the farmers’ perspectives of soil degradation. Social constructivist studies acknowledge that knowledge can be constructed by different stakeholders, and environmental issues can be subject to different interpretations. Such an approach posits that there are multiple ways that knowledge about environmental issues can be generated and local people’s perceptions about their environment and environmental issues and the context within which they occur are equally as important and valid as that of scientists. The constructivist approach to data collection is to get to the stories people use to describe their own lives by, while acknowledging these versions are not always fact or true pictures of reality [16].The research methods were primarily qualitative and included semi structured interviews and focus group discussions, as well as elements of participatory rural appraisal (PRA) such as transect walks and wealth ranking [17]. These methods were used to investigate perceptions of land degradation; especially declining soil fertility and crop yield. All the individual interviews and notes were recorded and transcribed. These were then coded according to themes and analysed using NVIVO qualitative analysis software. In all 22 male farmers were interviewed.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Perceptions of Soil Degradation

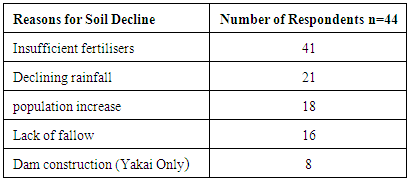

- Farmers were asked if there had been a decline in their soils quality and productivity and to articulate reasons for their answers. Most farmers interviewed perceived a decline in soil fertility and crop yield. This decline in soil fertility and consequently of crop yields was most important indicator of soil degradation mentioned by farmers in the study, but this was not viewed in isolation, but related to the quality and quantity of inputs into the soil. Soil is described as ‘dead’, ‘tired’ or even ‘disturbed’. Farmers complained that there was a marked decline in yield as a result, and that they produced significantly less food than they did in the past and this applied particularly to the main food crops of millet and sorghum. They acknowledged increasingly the number of damis (bundles) of grain they produced were not sufficient to feed their families for a whole year. According to them, this was not the case in the past. Farmers gave a variety of reasons for the perceived decline in soil fertility and subsequently in crop yield.

|

3.2. Importance of Fertilisers

- Farmers generate taki themselves at home from the collective household livestock, including those of their wives and children. The amount of taki a household can generates is limited to the number of livestock available in the household. Farmers acknowledge that it is an important limiting factor in their agricultural productivity. Low fertiliser use is regarded as one of the major constraints of smallholder agriculture in Nigeria [24]. There was a consensus among all farmers, that taki alone is no longer enough and must be supplemented with inorganic fertilisers, which they call takin zamani. One farmers comment illustrates this point“The main problem I have is that the manure does not work as well as the fertilizer. No matter how much of it we apply, it is just not as effective as the fertilizer. A handful of fertilizer will give you a better yield than a barrow of manure. But it is difficult to get, and it is expensive even when available”.Inorganic fertiliser is seen as chemical gold, the magic elixir that transforms soil and results in a good crop yield. All farmers believed that without fertiliser, yields will remain low, and indeed often are, because inorganic fertiliser is expensive, often unavailable or available in insufficient quantities. Almost every farmer interviewed felt that with enough fertiliser, yields would improve dramatically and that even though taki was not sufficient anymore, the addition of fertiliser can make up the deficiency.Although there are annual allocations of subsidised fertiliser to every ward from the local government, farmers complained that most times, it is too little, too late. They are then forced to buy the fertiliser at market rates, which are unaffordable for many of the farmers. At any rate, no farmer interviewed was wealthy enough to buy enough fertiliser for his farms. The following comments illustrate farmers’ frustrations at their inability to acquire what they perceive to be a crucial input into their farming:“The fertiliser allocated to us does not get to us. This year I haven’t gotten a single grain of fertiliser. And you know farming cannot thrive without fertiliser. Even in the past, we had to use manure to get a good yield. Now it is fertiliser we have to apply, because the manure is not always enough”. Chemical fertilisers are widely promoted by rural development programmes and in government policies to improve soil fertility, but have proved unsustainable mainly because most farmers cannot afford them and as a result its use is still at a minimum among smallholder farmers [5]. It is at minimum not due to the lack of acceptance of its usefulness and benefit but due to two major things - availability and cost. This observation is substantiated by all the interviewees. All the farmers would prefer to get more fertiliser if it was available at an affordable price. The high price is because of the parallel sale of subsidised and free market fertilisers, and this is seen to provide an avenue for illegal diversion for corrupt officials. Farmers believe inorganic fertiliser is vital for improved yield, if they could have access to it. Many do not, and those who do are only able to apply minute quantities. Its scarcity and cost make it out of the reach of all but wealthier farmers in any appreciable quantity, but that did not stop all farmers interviewed from bringing up the issue of fertiliser. It is interesting that although from the interviews it appears to contribute very little to the inputs farmers make into their farming, it looms disproportionately in their minds. Inorganic fertiliser may be used in very little quantities, but its importance is underscored by farmers’ insistence on its usefulness and contribution to soil fertility. Its significance may be underestimated by many of the researchers in the KCSZ who often have a somewhat idealistic view of the use of organic fertiliser (taki) and may overestimate its capability of sustaining the drylands. In their quest for inorganic fertiliser farmers are in no way rejecting the use or importance of taki. In fact, many farmers maintain that a mixture of both organic and inorganic fertilisers is best for maintaining soil nutrients. Farmers recognise complex interactions of yield, rainfall, soil fertility and technology, so their perceptions may reflect changes in social and economic factors differs from farmer to farmer [14].

3.3. Differences between the Two Communities

- There were a few differences in perceptions between the two communities which are worth noting. The proximity of Bemun to larger markets in neighbouring towns and to Kano city, and the remoteness of Yakai also affect these perceptions. In Bemun there are other options for improving soil fertility management; urban waste from Kano city known as shara, and poultry manure from nearby commercial ventures are available options. Higher annual rainfall also means better growing conditions.In Yakai, many men mentioned the decline in livelihoods brought about by the damming of the river Huda upstream and how that had affected village livelihoods, especially in the dry season. According to several farmers, Yakai used to be a hub of dry season activity including fishing and dry season farming of rice and vegetables, but this has significantly declined as a result of cutting off the water supply. The relatively drier ecology of Yakai and remoteness to markets are important influences on perceptions.

4. Conclusions

- Perceptions of environmental change are intrinsically linked to social, political and economic realities of local people. In this study a majority of the participants bemoaned their farms’ inability to produce as much yield as it did in the past. But they also acknowledged that the inputs into agriculture have declined. This is similar to what other studies [12] have noted, different social actors in the KCSZ evaluate their resource base differently and local perceptions of the loss in soil fertility is related to the increasing difficulty in getting both inorganic and organic fertilisers. The paper has shown that in both villages, farmers perceptions of land degradation is related to their socioeconomic circumstances and to ecological characteristics of their environment, particularly rainfall. Farmers focused on the importance of agricultural inputs to soil fertility. Socioeconomic factors are clearly the driving forces in management of soil fertility. Throughout the study, the inherent properties of the soil were not viewed as being as vital as the external inputs, and it was up to the individual farmer to maximise his yield through any means possible, including inputs of labour, nutrients and farm management. The abilities and attitudes of farmers are important influences on their vulnerability to and perceptions of degradation. Research suggests that a combination of organic and inorganic fertilisers is the realistic scenario to maintain soil fertility in Africa ([24-26]), an approach known as integrated soil fertility management (ISFM). ISFM articulates the maximum use of all available fertilisation strategies, both organic and inorganic. The findings from this study support this assertion, and suggest that government policy on fertilisers must be attuned to the farmers needs and focus on improving both availability at the right time, and price. This must be done as a matter of urgency, as the dependence of soil fertility management on the socioeconomic conditions of the farmer and their access to this vital resource is a crucial element affecting farming, and consequently poverty and food security in the two areas, and even in the region as a whole.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML