-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2016; 6(3): 63-65

doi:10.5923/j.re.20160603.03

Socioeconomic Demographics of a Bushmeat Market Town in Rivers State, Nigeria

M. Aline E. Noutcha, Alfred I. Omenihu, Samuel N. Okiwelu

Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, University of Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Samuel N. Okiwelu, Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, University of Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

More than 1.2 metric tonnes of bushmeat, excluding elephants are harvested monthly in Nigeria. Wildlife populations are declining further by farming, logging and live-capture for export trade. Bushmeat research has tended to be driven by conservation rather than livelihood concerns. Livelihood linkages are therefore still not well understood. The socio-economic demographics of the bushmeat market town, Omagwa, Rivers State, Nigeria, was investigated. It is located in the lowland rainforest on the expressway, linking two state capitals. The Port Harcourt International Airport is at the southern periphery of the town. Most of the town’s graduates were in the group not involved in the bushmeat trade and vendors in the trade. In contrast, the least educated were hunters and middlemen involved in the trade. Approximately, 60% of those not involved in the bushmeat trade were in the low income range, while only 30% of those involved in the bushmeat trade were in the low income range. However, the difference in incomes between those in the trade and the segment not involved in the trade was not significant. Similarly, the differences in incomes among vendors, hunters and middlemen were not significant. The pattern in educational status among the various groups was similar. Educational status across the community was adequate for the introduction of enlightenment campaigns on conservation, sustainability, selective hunting, etc. community-based wildlife management is recommended to ensure that all families benefit from the resource.

Keywords: Bushmeat Trade, Participants, Non-participants. Education, Economic status, Nigeria

Cite this paper: M. Aline E. Noutcha, Alfred I. Omenihu, Samuel N. Okiwelu, Socioeconomic Demographics of a Bushmeat Market Town in Rivers State, Nigeria, Resources and Environment, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 63-65. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20160603.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Bushmeat is a term used to identify meat of terrestrial wild animals, killed for subsistence or commercial purposes throughout the humid tropics of America, Asia and Africa [1]. In an effort to expose the global nature of hunting wild animals, resolution 2.64 of the IUCN General Assembly in Amman, Jordan (October, 2010) referred to it as wild meat, but a more worldwide and acceptable term is game [1]. Unsustainable hunting has caused both local and global extinctions [2]. More than 1.2 million metric tonnes of bushmeat, excluding elephants are harvested monthly in Nigeria [3]. Bushmeat is a good source of protein for rural dwellers, but populations of wildlife have declined steeply, due to hunting habitat modification by farming, legging and live-capture for export trade [4]. Meat from the Korup National Park, Cameroon was US$400,000 annually [5]. This illustrates the economic importance of the trade at a regional level and therefore at the national level would be a significant contribution to the economy of the nation. Antsey [6] found that in Liberia, although there was a total ban on all wildlife utilization since 1988, the commercial trade and subsistence bushmeat were valued at US$42 million annually. The total worth of the trade in markets and rural consumption in Gabon was estimated at US$21 million annually [7]. It was against this background that studies were initiated at the major bushmeat market town, Omagwa in Rivers State on species composition, abundance, cost of the carcasses and the resilience of the Greater Cane Rat, Thyronomys swinderianus [8, 9]. Bushmeat research has tended to be driven by conservation rather than livelihood concerns. Livelihood linkages are therefore still not understood. Pro-poor conservation addresses the need to ensure that poverty issues are integrated into the work of the leading conservation agencies [10]. Studies were initiated on the socioeconomic demographics and attitudes to conservation of the Omagwa residents. Socio-economic demographics of bushmeat market towns and villages have been conducted in Ghana, Cameroon, Gabon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Equatorial Guinea and Congo Brazzaville, but not much has been done in Nigeria [3]. The current study focusses on the socioeconomics demographics of residents in the bushmeat market town, Omagwa, Rivers State, Nigeria.

2. Materials Methods

- The bushmeat market town, Omagwa is at 4°98'N and 6°91'E, in the Ikwerre Local Government Area, Rivers State. It is the main conduit for the sale of almost all the wildlife harvested in the catchment area of approximately 54km2 [8]. The area is lowland rainforest, dominated by secondary vegetation and fragmented by farms. The town is located on the busy interstate expressway that connects the state capitals of Port Harcourt, (Rivers State) and Owerri (Imo State). The Port Harcourt International airport is located at the southern edge of the town.Data were obtained by the use of questionnaires, personal interviews and observations (Participatory) across all the villages in the town over a 6-month period. Three hundred and fifty questionnaires were administered. Responses were received from 190, distributed as follows: Residents not involved in the bushmeat trade (103), residents involved in the bushmeat trade (Hunters- 42, Vendors- 37, Middlemen- 08).

3. Results

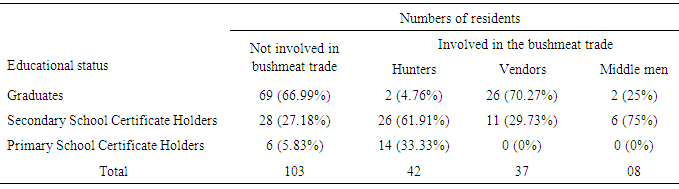

- Residents not involved in the bushmeat trade comprised the bulk of educated villagers; approximately 70% in this group were graduates. Similarly, about 70% of the smaller group of vendors were graduates. In contrast, only approximately 4% and 25% of hunters and middle men respectively were graduates (Table 1). However, the one-way ANOVA showed that there was no significant difference in educational status between those involved in the trade and residents not involved in the trade (p-0.80 >5% significant level). Similarly, there was no significant difference in educational status among hunters, vendors and middlemen in the trade (p-0.40>5% significant level).

|

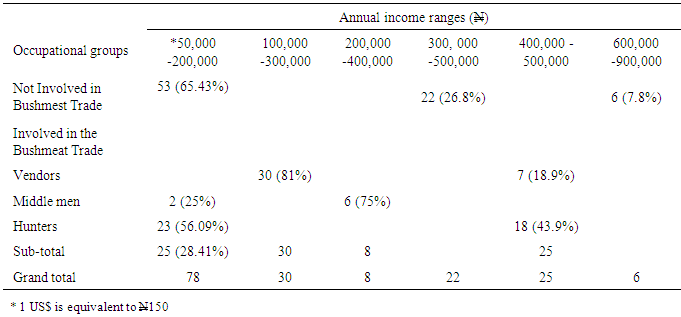

3.1. Income Distribution among Residents at Omagwa

- Among residents not involved in the bushmeat trade, the income distribution was: 54 (65.8%) (

40, 000- 200,000); 22 (26.8%) (

40, 000- 200,000); 22 (26.8%) ( 300, 000-500,000); 6(7.8%) (

300, 000-500,000); 6(7.8%) ( 600, 000- 900,000). The income distribution of residents involved in the bushmeat trade was: Vendors- 30(81%) (

600, 000- 900,000). The income distribution of residents involved in the bushmeat trade was: Vendors- 30(81%) ( 100, 000-300,000), 7(18.9%) (

100, 000-300,000), 7(18.9%) ( 400, 000-500,000); Middle men- 6(75%) (

400, 000-500,000); Middle men- 6(75%) ( 200, 000-400,000), 2(25%) (

200, 000-400,000), 2(25%) ( 50, 000- 200,000); Hunters – 23 (56.09%) (

50, 000- 200,000); Hunters – 23 (56.09%) ( 50, 000-200,000), 18 (43.9%) (

50, 000-200,000), 18 (43.9%) ( 400, 000-500,000) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in income between those involved in the trade and the residents not involved (p-0.74>5% significant level). The difference in incomes among vendors, hunters and middlemen in the trade (p-0.55>5% significant level).

400, 000-500,000) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in income between those involved in the trade and the residents not involved (p-0.74>5% significant level). The difference in incomes among vendors, hunters and middlemen in the trade (p-0.55>5% significant level).

|

4. Discussion

- The high number of graduates among residents not involved in the bushmeat trade was probably related to the fact that some of them work at the airport, supervisors in airport hotels and teachers in public and private schools in the town and its environs. The high number of vendor graduates among those involved in the bushmeat trade might be ascribed to the high unemployment rate in the country that steered graduates to fill this occupation that provided a steady income. As vendors, their communication and marketing skills should be excellent. The educational standards of all stakeholders in the town were adequate for the introduction of enlightenment campaigns on conservation, sustainability, selective hunting, etc. The large number of residents not involved in the bushmeat trade, whose annual income was low,

50, 000-200,000 was probably because a substantial number in this group were farmers. In contrast, among residents involved in the bushmeat trade, less than 30% were in the low income range. Although the difference in incomes between the two groups was not significant, these percentages indicated that an individual was better off being involved in the bushmeat trade at Omagwa. Other studies concluded that the bushmeat trade was a lucrative business in Africa [7, 10]. Unemployment will continue to pose a threat to biodiversity conservation; the increasing trend of political instability on the African continent may also lead to loss of endangered species. Improved government policies on conservation education and job creation are the major steps to protect the country’s wildlife. In the interim, the new community conservation narrative which stressed the need not to exclude local people either physically from protected areas or politically from conservation policy process, but to ensure their participation might be introduced to ensure that all segments of the Omagwa community benefited from the resource [12-13].

50, 000-200,000 was probably because a substantial number in this group were farmers. In contrast, among residents involved in the bushmeat trade, less than 30% were in the low income range. Although the difference in incomes between the two groups was not significant, these percentages indicated that an individual was better off being involved in the bushmeat trade at Omagwa. Other studies concluded that the bushmeat trade was a lucrative business in Africa [7, 10]. Unemployment will continue to pose a threat to biodiversity conservation; the increasing trend of political instability on the African continent may also lead to loss of endangered species. Improved government policies on conservation education and job creation are the major steps to protect the country’s wildlife. In the interim, the new community conservation narrative which stressed the need not to exclude local people either physically from protected areas or politically from conservation policy process, but to ensure their participation might be introduced to ensure that all segments of the Omagwa community benefited from the resource [12-13]. 5. Conclusions

- Educational status across the community and the pervasive positive attitude to preserving the wildlife resource for future generations (unpublished) were encouraging indicators of enlightenment campaigns on conservation, sustainability, selective hunting, etc. community-based wildlife management is recommended to ensure that all families benefit from the resource.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Authors are grateful to community members who participated in the study for providing information at every level.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML