-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2015; 5(6): 192-199

doi:10.5923/j.re.20150506.03

Traditional Energy Discourse: Situation Analysis of Urban Fuelwood Sourcing in Northern Nigeria

Ali Ibrahim Naibbi

Department of Geography, Northwest University, Kano, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ali Ibrahim Naibbi, Department of Geography, Northwest University, Kano, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2014 [1] noted that addressing the global energy poverty challenge will require concerted effort if the needs of the world’s 2.7 billion people who rely on traditional biomass for cooking are to be met.Despite this high dependency on traditional energy, particularly in the developing countries, their strategies of urban fuelwood sourcing, in recent times, are not substantially reported. This may not be unconnected with the fact that they do not seems to be considered as part of the complex energy issues of these regions. It is important for these to be monitored particularly in countries like Nigeria, where more than 130 million of its estimated 170 million people depend on fuelwood for cooking. This study contributes to the ongoing discourse on energy trilemma. The study examines an urban commercial fuelwood sourcing using participant observations in a case study area in northern Nigeria. The study finds that the activities of commercial fuelwood sourcing are highly organised but unsustainable. The study concludes that there is the need for policy makers to swiftly intervene by providing alternatives in order to protect the remnants woodlands from the aggressiveness of the fuelwood collectors who solely depend on the business for their livelihood.

Keywords: Firewood, Fuelwood, Traditional Energy, Commercial Fuelwood, Energy Trilemma

Cite this paper: Ali Ibrahim Naibbi, Traditional Energy Discourse: Situation Analysis of Urban Fuelwood Sourcing in Northern Nigeria, Resources and Environment, Vol. 5 No. 6, 2015, pp. 192-199. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20150506.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

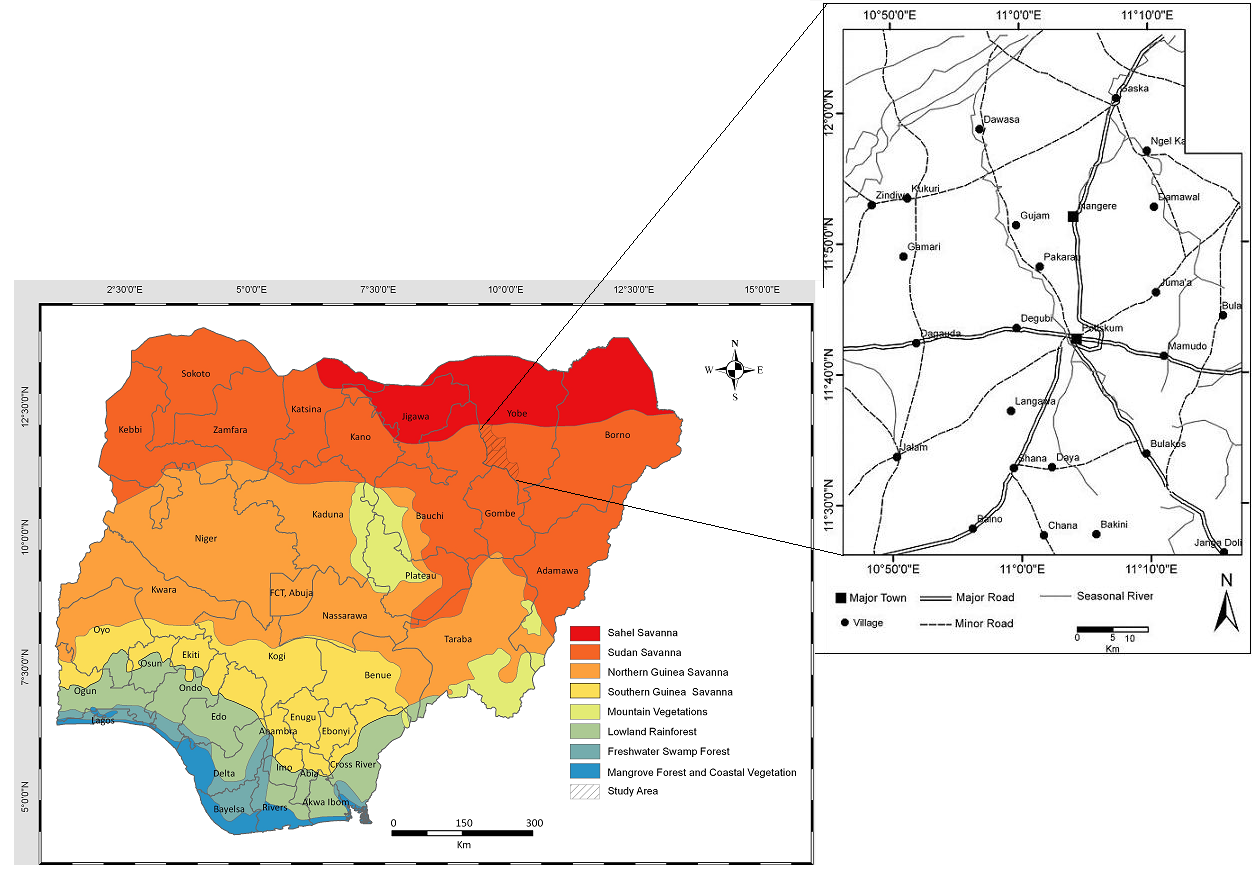

- Energy trilemma, which involves the interconnected, but often competing demands of energy security, climate change mitigation and energy poverty, was recently argued as being part of the complex issues surrounding energy access in the world [2]. Although, Nigeria recorded a high number of fuelwood users in its 2006 national census (National Population Commission (NPC), [3]), compared to other conventional energies like fossil fuels and electricity, such records are not well documented particularly with regards to the sourcing of the fuelwood. For example, the excessive use of fuelwood for cooking in Nigeria, particularly in the northern part, clearly demonstrates the insufficiency of other energy alternatives in the region ([4], [5]). The lack of alternative energy sources and the increased distance to the fuelwood collection centres have promoted the commercialization of fuelwood in the region. The activities of the commercial fuelwood vendors were mostly regarded by scholars as the potential cause of the active deforestation in most semi-arid zones of developing countries [6]. Given the importance of fuelwood as a cooking fuel option in Nigeria ([7], [8]), its supply source needs constant monitoring, particularly in the arid northern part of the country, where most areas are already facing the peril of forest degeneration [8].FAO [9] showed that apart from the southern part of Nigeria, where the high forest is found (Figure 1), there is no any other region in the country that is self-sufficient in the supply of fuelwood. Though, the Savannah area in the northern region is large (Figure 1), its fuelwood production is far less than that of the high forest zone of the southern region. This could be attributed to the former’s increasing demand for fuelwood as a result of its population increase and the conversion of woodlands into farmlands [7], [10]. However, if the source of fuelwood supply in the northern part of Nigeria is shrinking as portrayed by FAO [7], [9], then what is the current and future outlook of fuelwood in the region and the country at large? These questions need answers if the country is to avoid running out of this important energy source [11], which is what this research addresses.

| Figure 1. Nigerian vegetation zones and the location of the Study area (Source: Adapted from [8]) |

1.1. Background of Fuelwood Sourcing

- The activities of sourcing fuelwood for domestic usage were in the past considered to be solely the task of women in Africa ([14-16]). For example, Williams’ [14] research on the social organisation of fuelwood procurement and use in Africa highlighted that women are the dominant sex in executing the task of collecting and using fuelwood. His findings also showed that women collect fuelwood from short distances and in small quantities as a daily routine. However, with the recent change in the state of fuelwood (shortage and distance to the collection centres), there is now a shift in the paradigm that women were the primary collectors of fuelwood in Africa [17]. The new fuelwood situation resulted in the active participation of men in the collection process. Men are now engaged in long distance travel to procure fuelwood as a means of livelihood, in many instances, using trucks to transport the wood ([6], [15], [18]). These developments constitute danger to the environment, because in most of the developing countries, where fuelwood has been considered as an option for cooking, woodlands are treated as an open access resources ([19-21]). To put in another way, commercial fuelwood business men do over-exploit the woodland resources with no regard to its future sustainability. This is another area that this study investigates.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

- Like most northern Nigerian towns, the study area ‘Potiskum’ which is located in the southern part of Yobe State (Figure 1) is primarily an agricultural town [8]. It falls within the Sudan Savannah vegetation zone, and is characterised by a hot and dry climate [22]. The major factor contributing to population change in the area is migration which contributes up to about 2.5 percent of the estimated four percent average annual growth rate [13].

2.2. Data Collection

- The data for this study was generated following an in-depth field study of the cooking energy poverty in northern Nigeria, where the researcher engaged with the commercial fuelwood vendors in Potiskum and its environs from July to October, 2010 and a subsequent follow up in February, 2015 as part of the continued process of participant observation.The vendors in Potiskum organised visits for the researcher to a few fuelwood collection centres. Clissett [23] reported the importance of a prolonged engagement and continual observation of the participants of a study. He maintained that by constantly observing the participants, the researcher will have more time to learn their culture and context of the issue under investigation. This is essential, because it will also enable the researcher to develop a personal relationship of trust with the participants. On the other hand, without a regular observation and prolonged engagement with the participants, there is a risk that the researcher might overlook some of the critical aspects of the research ([23], p. 104). It is worth nothing that due to the sensitivity of the fuelwood business, all the respondents were selected opportunistically (see for example, [21], p. 1609). The subsequent section presents the result of the field observations.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Mode of Commercial Fuelwood Operation: A Field Trip Experience

- The current nature of fuelwood collection in the study area has changed from subsistence to a commercial status, because of the variety of engagements and the job opportunities it creates. An important observation from the fuelwood business operations is that they all use simple tools in the procurement and processing of fuelwood, which was contrary to the initial assumption of the researcher who thought that the vendors are using sophisticated tools (such as chainsaws) in the processing of fuelwood. Another important observation made in the business that was not reported in earlier literature can be illustrated from the author’s observation of the vendors’ activities, which was confirmed by the fuelwood vendors’ chairman of the Potiskum central market that there are two major modes of fuelwood collection in the area. One is locally called ‘Dandi’ and the second one is called ‘Daba’. These two collection strategies are discussed below as observed in the field using some photographs taken (Figures 2 and 3 respectively) to demonstrate the activities.

3.1.1. Modes of Fuelwood Collection Operation ‘Dandi and Daba’

- Dandi is the kind of fuelwood collection operation where the workers that engaged in the procurement of fuelwood, hire a vehicle for a day trip. They normally leave in the morning, and return to the town in the evening and sell the wood they have collected for the day to the market vendors. This operation is very popular among labourers, who organised themselves (between five to ten people), and travel into the forest, in order to supply the wood daily. A trip to the Burai forest near Jangadole Village (Latitude 11.460734 N, Longitude 11.329507 E), south of Potiskum town on the 27th July, 2010 highlights this operation. The fuelwood collected from this forest are the remaining roots of a dead tree (Bauhinia rufescens locally called ‘Matsagi or Jalahe), which had been previously cut down. The operation involves digging the ground in order to uproot the remains of the dead tree stump. The mode of operation of this particular collection site was obviously laborious as can be observed in Figure 2. The workers spend less time looking for the dead stump (approximately 3 minutes) before digging it out which also last between 8 to 10 minutes depending on the size of the dead stump. Note that the operation observed in this particular forest does not involve cutting down of live trees.Unlike the Dandi mode of collection operation, the Daba collectors remained in the forest for a number of days (sometimes weeks) in order to stock enough wood that can be collected using a bigger truck for onward delivery to the market in the towns. This kind of operation is very popular among the influential vendors whom encouraged the collectors by supporting them with all the necessary material assistance (food and advance payment for the goods). Refer to Figure 3 for illustrations. The author’s initial arrangements with the vendors to observe the conduct of the Daba operation in Buni Yadi forest of Gujba LGA in Yobe state on 2nd August, 2010 and ‘Wawa’ forest in Gombe state on 10th October, 2010 failed. The visits were cancelled due to lack of a guide that is familiar with those forests. Upon further inquiry, an important personality in the area (‘Sarkin Daji’- the traditional chief of one of the communities’ forest) offered to guide the author to ‘Wawa’ forest on the 12th October, 2010. The ‘Wawa’ forest is located at 10.82° N, 11.03° E, about 160 kilometres south of Potiskum town. The fuelwood collected from this forest is a combination of both live and dead trees. From Figure 3, one can observe an evidence of fresh wood left-over leaves, and tyre tracks of vehicles leading to the inner forest.The tracks were created as a result of fuelwood collected from the inner forest. These workers stay in this forest for weeks in order to gather the fuelwood. They then call their vendors who lived in the cities to organise and move the fuelwood from the inner forest (using smaller trucks) to the collection centre ‘Daala’ (Local name, meaning Pyramid). As soon as there is sufficient fuelwood in the Daala, a bigger truck is hired to collect the entire load for onward delivery to the cities. The load in figure 3 was on its way to Kano city, which is about 400km away from this forest.

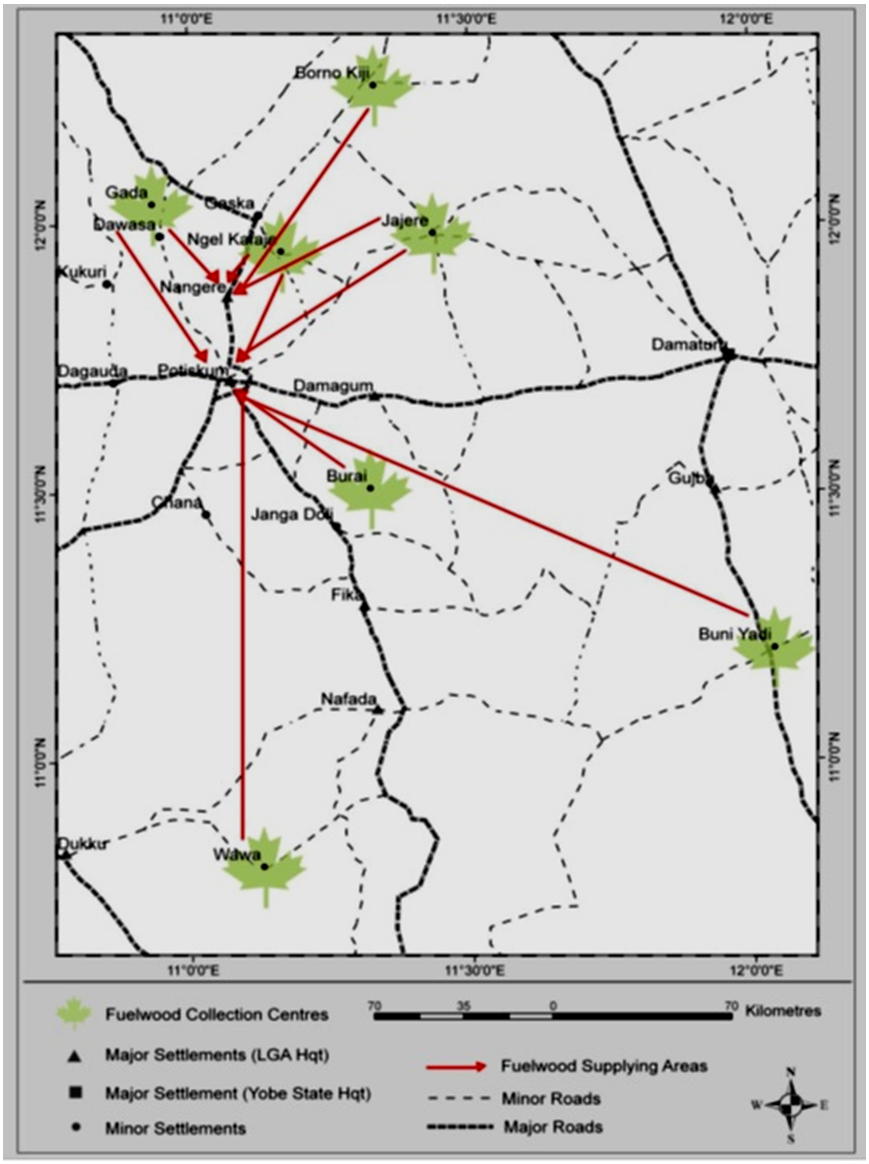

3.2. Transportation and Fuelwood Procurement Strategy

- The concept of intervening opportunity of spatial interaction theory assumed that decisions are influenced not just by the size of the destination or distance but by the combination of these two factors, that is spatial dominance [24]. In other words, the decision to move is largely influenced by the knowledge about, and the positive perception that the destination exerts the greatest amount of spatial dominance than other origins. This was largely the reason why the local vendors now travel far distance in order to source the fuelwood due to the deplorable state of their immediate surrounding’s fuelwood sources (refer to figure 4).

| Figure 4. Fuelwood Procurement Centres (Source: Author’s) |

4. Policy Implications

- Although, some of the past Nigerian government’s policies have supported deforestation (see for example, [8]); there are many policies that were aimed at improving the forest reserves and the restoration of forest areas in the country. Such policies include the government support for afforestation programme through the ecological fund, which was provided directly to the affected state governments. However, this assistance has not been managed properly ([25]). Also, the performance of the Nigerian government’s afforestation programmes is inadequate because there is no recourse to periodic checks of the aftermath, in order to assess the success or failure of the programme. This has resulted in the failure of most afforestation programmes in the country. However, it should be noted that government afforestation programmes in Nigeria were primarily aimed at reducing the effect of desertification in the arid north, and are therefore not for fuelwood acquisition. Conversely, since the commercial vendors (particularly the Daba mode of collection) operates ‘unlawfully’ and do not replace the trees they collect from the forest, they are mostly seen as part of the overall problem of woodlands degeneration in the area. This is part of the reasons why the acquisition of fuelwood carried out in northern Nigeria, requires an urgent intervention, because while the natural woodlands are being collected for fuelwood in the wild, no attention is given to replace them by the fuelwood collectors or the government. This is also one of the reasons, why, for example, in the Potiskum area, fuelwood collection has reached the worst state, where the collectors resort to the uprooting of dead tree stumps in Burai forest, because there was no replacement strategy after the primary deforestation was carried out. One possible way to reduce this issue in the short term is through a robust monitoring afforestation. An effective afforestation programme that will target the commercial fuelwood vendors should be emphasised, by using rapidly growing species, such as the neem trees, which is very popular and accepted in the north. Also, the provision of access of the common forest (land)1 to the fuelwood collectors, has been argued by researchers in recent times ([26-28]) as a possible short term solution because it is expected that they would be more conscious of the environment as well as of their activities once they understand that they are also stakeholders of the forest resources.

5. Conclusions

- From the foregoing, it was obvious that the activity of commercial fuelwood vending is highly organised in the study area. The collectors are mostly locals who rely on simple modes of transportation systems to travel long distance in order to convey their goods to their buyers, using simple tools. In this way, fuelwood vending provides critical support to their incomes and a key source of low-cost energy. However, this situation was perceived to be a major factor in the accelerated process of environmental degradation (deforestation). Although there are laws enacted in order to discourage both the collection and trading of fuelwood in most developing countries, little has been achieved to stop this practice, which can be attributed to lack of awareness from the policy makers, of the relevance of commercial fuelwood activities to the local economy. Only a few researchers have pointed out the importance of commercial fuelwood in the socio-economic activities of the developing countries. Therefore, the authorities do not seem to be fully aware of the job opportunities in the business, which this paper highlighted. It was clear that the concept of the energy trilemma was demonstrated by the two modes of fuelwood collection operations (Dandi and Daba), which showed the effectiveness of the vendors in maintaining the supply of the commodity to the households at the detriment of the environment. Although both collection strategies concurred with the existing literature on the role played by distance and opportunities (intervening opportunities) in the creation of commercial fuelwood vending, this study considers that the sector needs to be appreciated and recognise by the policy makers in order to strengthen the positive aspect of it. This is because of the variety of unskilled jobs it creates. Note that this study is not offsetting this against the consequences of environmental damage caused by the vendor’s action, but rather highlights some of the potentials of the operation as an alternative source of employment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I acknowledge the assistance of the Potiskum main market fuelwood vendors association during the field trip.

Note

- 1. All land in Nigeria including its resources belongs to the government and one can only obtain it through lease from the government.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML