Mohammad Aljaradin1, Kenneth M. Persson2, Emad Sood3

1Tafila Technical University, Natural Resources Department, Engineering Faculty, Tafila, Jordan

2Lund University, Department of Water Resources Engineering, Lund, Sweden

3Tafila Technical University, Civil Engineering Department, Engineering Faculty, Tafila, Jordan

Correspondence to: Mohammad Aljaradin, Tafila Technical University, Natural Resources Department, Engineering Faculty, Tafila, Jordan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Scavengers play a major role in the waste management process in developing countries. This study analyzed the informal recycling activities carried out by scavenger in the Tafila region of Jordan. The results show that scavengers have an important role in the informal solid waste management (SWM) especially in term of waste reduction, minimization and material recovery. Significant values from the scavenged material make the scavenging somewhat a profitable business for poor people and could track more in the future. Socially scavenging tends to be acceptable in the community, especially with the increasing of the poverty and employments rates and became more acceptable in rural areas as it is already in urban areas. Despite the low level of education, the awareness for the negative health effect from working with waste was very high. The organizing of the scavenger work is suggested, since it would improve their working environment, income and living conditions. Therefore it should increase their contribution significantly to resource recovery.

Keywords:

Scavengers, Material recovery, Tafila, Jordan

Cite this paper: Mohammad Aljaradin, Kenneth M. Persson, Emad Sood, The Role of Informal Sector in Waste Management, A Case Study; Tafila-Jordan, Resources and Environment, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 9-14. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20150501.02.

1. Introduction

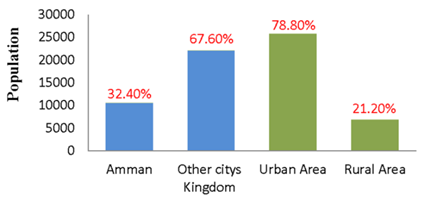

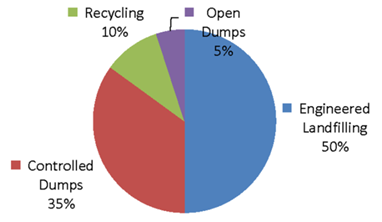

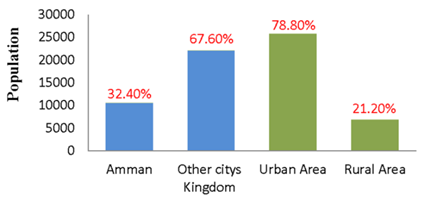

In Jordan resource recovery and recycling is very limited and undertaken by formal level through none governmental organization (NGOs) and informal sector mainly by poor individuals who make a living on the recovery of recyclable waste materials [1]. These are typically identified as scavengers. Some of their activities are carried out before the solid waste reaches the final disposal sites for the separation of recyclable materials. However much is done at the disposal sites. The scavengers recover material to sell for reuse or recycling, also they collect different items for their own consumption. They usually perform their work in a very primitive way without any protective measures for their health and safety. They are exposed to hazards and unhealthy work place environment which they are not fully aware of. This could lead to high risk of infection and disease transmission. Nevertheless, scavengers have an important role in the informal solid waste management especially in term of waste reduction, minimization and material recovery. A significant value of the scavenged material in combination with waste minimization makes the scavenging not only an income opportunity for poor people, but also serves the protection of natural resources and the environment. Poverty, high unemployment and demand for recyclables are there drivers. As these still appear in the foreseeable future, scavenging is likely to continue to exist [2]. Efforts to eliminate scavenging and to encourage scavengers to engage in other occupations usually fail [3]. Supporting scavenging can result in grassroots development, poverty alleviation and environmental protection. Studies have found that when scavenging is supported, scavengers can earn higher incomes than unskilled workers [4]. Besides, the scavenging process will lead to less money and time spent on collection and transportation [3]. Scavenging has been recognized recently in Jordan as an effective way for managing waste whereas it reduce the cost of formal waste management systems as it reduce the quantity of waste for collection [5-7]. But on the other hand, many objections for the involvement of children (Child labor) and the elderly in this sector are risen, as it expose them to significant health risk due to their daily contact with garbage [8], and it often hinders children from having any chance of a formal education. There is no legislation in the country forbidden scavenger from practicing their work but the Ministry of Social Development always tracks these children and turns them into specialized centers for rehabilitation.Child labor is a growing problem in Jordan see (figure 1). Officially 32000 children are engaged in child labor in sectors, but other unofficial statistics says that more than 53000 children are actually working [10]. Child labor has always been of Governmental concern, especially children engaged in hazardous situations or conditions, such as scavengers, but much have so far been done to reduce it. The authorities in Jordan consider scavenging as uncivilized practice and present a bad image for the country. They are often ignored or seen as burdens to efficient waste management processes. Yet economy can change that concept. In a country where 14.7% of the population lives below the poverty datum line and unemployment officially stands at 12.7%, scavenging becomes gradually more socially acceptable. Scavenging has become a way of life for many and turning into profitable business. Scavenging is sometimes claimed to improve efficiency in a society’s use of natural resources [11]. Scavenging cannot be wished away, however, nor can it be ignored. In any case a solution must be found to recognize the scavenger presence and maximize their role [12]. The informal recycling in Jordan was estimated to be around 10% from the total municipal solid waste (MSW) generated which represent around 196428 ton in 2009 (figure 2).  | Figure 1. Child labor in Jordan 2007-2008 (source: [9]) |

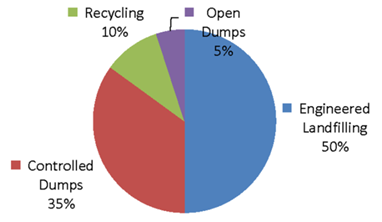

| Figure 2. The Methods of disposal in Jordan (Source: SWEEP 2010) |

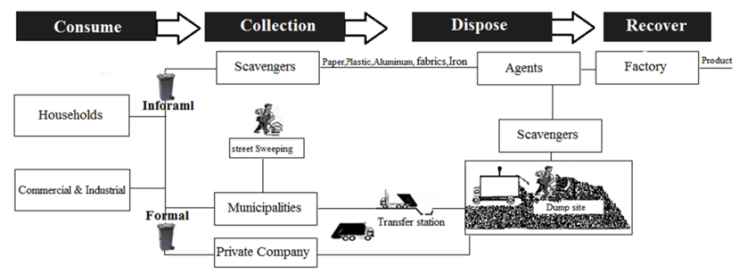

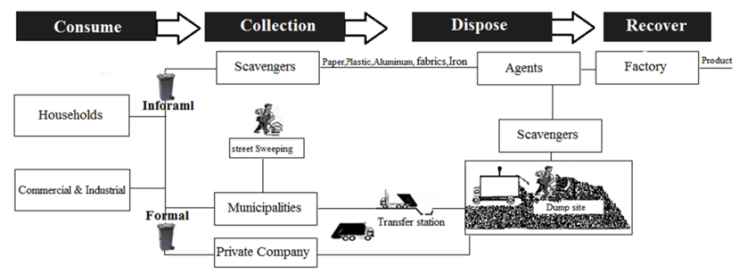

The role of scavengers in waste management is currently increasing in Jordan but without the proper and sustainable organization [13, 14]. The solid waste streams and the scavenger’s many roles in the waste management are presented in (Figure 3). | Figure 3. Flow chart for Solid waste streams and scavengers role in Jordan |

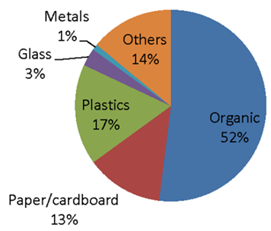

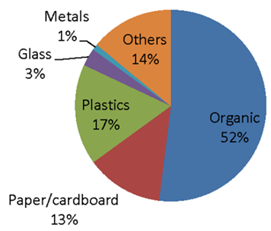

The materials most often collected are aluminum, plastic, paper, cardboard, glass, copper, and iron. Organics waste are the major fraction, as expected, since Jordan is a developing country, and food is the major component of the solid waste stream generated in developing countries [15], and the reset are decomposable and recyclable. The physical composition and typical percentage distribution of MSW in Jordan presented (Figure 4). | Figure 4. The Physical Composition of MSW in Jordan (Source: [14]) |

It is little acknowledged or even known that scavengers often contribute significantly to resource recovery and recycling of waste materials and can thus have a very positive impact on waste management systems [16, 17]. In Jordan a comparison of costs and benefits of scavenging is rarely conducted. This paper analysis the informal recycling activities carried out by scavenger in Jordan. Field visits and interviews among scavengers were conducted. The organizing of scavenger work under the umbrella of municipalities or private companies is discussed since it can increase their contribution significantly to resource recovery and recycling of waste materials, where it was very successful in many parts of the world [4, 18]. Furthermore, in the paper, the improvement of their working environment, income and living conditions is discussed.

2. Method and Material

2.1. Area Description

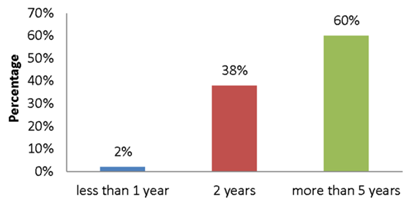

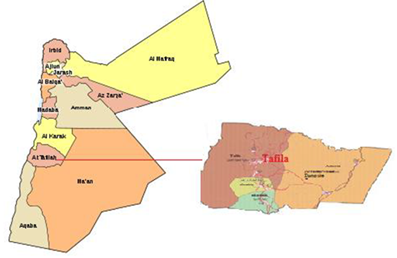

Tafila is a rural center in the south of Jordan, with a municipal population of 80,000 people, Tafila governate consists of four municipalities (Figure 5). The solid waste generation in Tafila city which is the main municipality with a population of 49,000 people is around 40-45 tons/day or 0.9 kg/capita/day. | Figure 5. Map of the study area, Tafila region (source: [19]) |

The responsibility for MSW collection and transportation to the final destination sites lies with the Greater Tafila municipality, while the operation and management of the final disposal sites is the responsibility of the Common Service Council (CSCs) in the governate. The solid waste is collected by compacter vehicles; these vehicles are owned and operated by Tafila Municipality. Each compacter has its crew which is usually two employees and a driver. Each round of service for each compacter takes around 5 hours; they start to collect waste from the containers which are distributed all over the entire city early morning about 5 am, but another round usually for markets, shops and poultry industry in the evening. After finishing each round the compactors directly bring their load to the disposal site. Tafila waste disposal site (Jurf aldarweesh) is an area of 550000 m2, situated 35 km south-east from the center of Tafila (see Figure 5). The dump site receives 120 tons/day from the four municipalities of the governate. The area of the dump site is mostly rocky, which makes it difficult to dig trenches for the daily cover. Trenches are opened through the rocky ground and the waste is dumped without compaction and without lining. The waste surface is covered daily with a thin layer of soil. However, before the covering process is initiated, some scavenging is done inside the dump site by the employees working there. In the past, the municipality used to rent the dump site to private contractors. The contactors dug up the waste and collect the recyclables to be solid to interested companies.

2.2. Investigation Scheme

This work is based on data collected via personal interviews among scavengers. 100 scavengers were interviewed during 10 days in Tafila region. The interviews were conducted during October 2010. The data collections targeted scavengers at work and at home. Therefore, the interviews were conducted on the streets and scavengers home. It was designed to answer these questions; the social demographic characteristics of the scavenger; age, sex, level of education, marital status and then the source, amount, type and place of the waste collected, purpose and benefits from the collected waste, the negative effect of working with waste on their health and finally the society acceptance of their work.

3. Result and Discussion

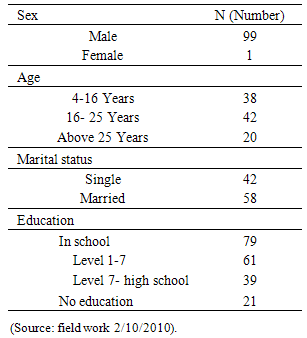

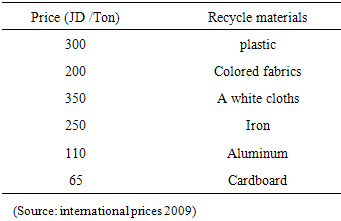

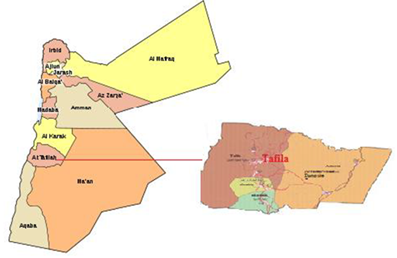

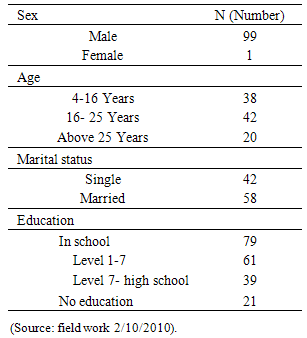

The social, economic and demographic characteristics of the scavengers are presented in Table 1. Table 1. The demographic composition of the questionnaires

|

| |

|

The interviewed were mainly male, 62% aged between 16 and 50 years with an average of 31 years where they are mostly married. 38% of them were children of less than 16 years. The majority of the respondents are below high school level of education were 61% from the only have chance to go to school 79%. The portion with no education at all was 21%. Concerning the economic situation (Table 2), it is found that approximately 78% of the people earn more than 250€ per month, the minimum level of salary in the public sector in the country, this concur with a recent study conducted by Amman municipality, where was found that the average monthly income for scavenger ranged from 300 to 900€ [20]. More than 50% of the interviewed are married, where, 69% live in their own houses, whereas the remaining represents those renting from a landlord. 48% of the scavengers work for 4-8 hours daily which implies that scavenging is the only income as supporting their family members. Instead, 52% work for 2-5 as it is considered as a supplementary income to the family and sometimes just for the scavenger himself. 33% own a car, this advantage mange them to collect more and go further distance, and it is usual in family which have more than one person contributing to scavenging.Table 2. The Economic situation for the scavengers in the survey

|

| |

|

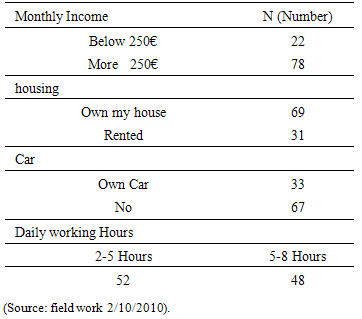

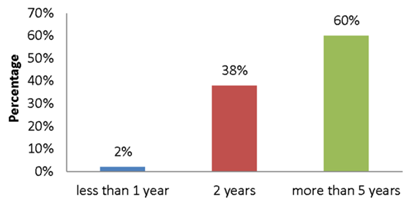

From (figure 6), 98% of the scavenger works said they had worked for more than two years in scavenging; this could be because scavenging tends to be a profitable business or because scavengers do not have another opportunity to get a job due to the low education levels. | Figure 6. The working experience in scavenging (Source: Field Work 2/10/2010) |

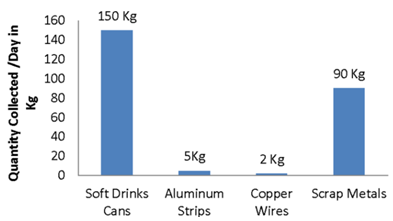

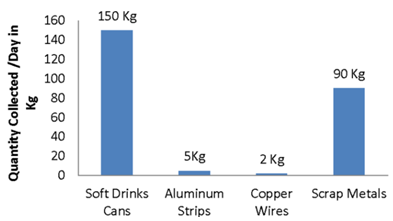

The most common collected type during a working day form all the scavengers is soft drink cans with around 150 Kg and scrap metals around 90 Kg as show in (figure 7). | Figure 7. Average Quantities collected by 100 scavenger during a working day (source: field work 2/10/2010) |

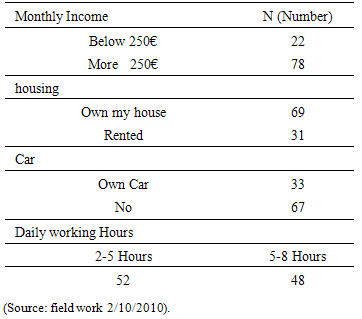

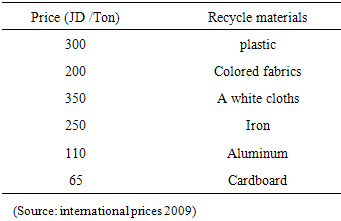

Many scavengers specialize in collecting aluminum cans (soft drinks), and work individually in the city streets. This work is done usually by teenagers. They work for 2-5 hours every day before and after schools, beginning at 6-7 in the morning and from 2-5 in the afternoon. They walk long distance every day. The fact that they did not have a boss in the work gave them flexibility in working hours. The quantity of material collected every day ranges from 2 to 5 kg of aluminum cans, depending on the scavenger efforts. Other specializes in collecting waste directly from rubbish bins and containers located in front of restaurants, cafes and public markets and sometimes between houses in the neighborhoods. They collect almost everything except the food waste. This work is usually done by the children of lower ages. By the end of the day the collected material is then sold to trash dealer’s (agents) whom usually preform more sorting and cleaning before selling the material further to specialized industries at market prices. However, if the scavenger owns his car, he can store and transport scavenged material for latter cleaning and sorting, and thus gets a higher value for the collected material when selling it. The prices of the sorted materials depend on the international prices for the used materials as shown in table 3.Table 3. The prices of some sorted materials

|

| |

|

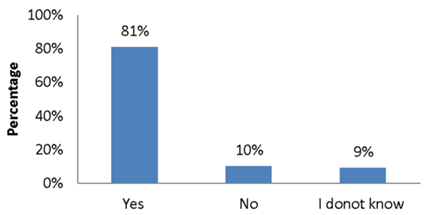

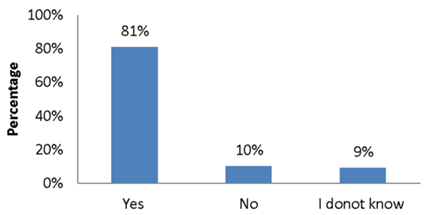

Despite the low level of education for many of the scavengers, the awareness between interviewed was high as 81% on the negative health effect from working with waste, see (figure 8). However, usually as they work in a very primitive way without any protective measures for health and safety they could be exposed to hazards which they are not aware of. | Figure 8. The awareness about negative effect on their health (Source: Field Work 2/10/2010) |

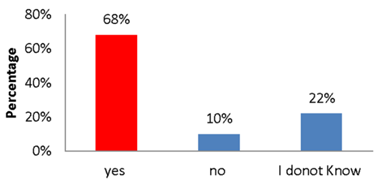

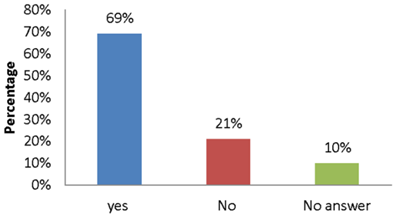

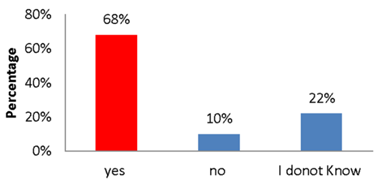

The scavenging tends to be socially acceptable in the community, especially with the increase of the poverty rates and employments. Before it was acceptable in urban areas, but nowadays it is acceptable even in rural areas. 68% answered “Yes it was acceptable” on this question. Sometimes they got encouragement from relatives and neighbors to work as scavengers, see (figure 9). On the other hand, some of scavenger had been forbidden by some families to enter their neighborhoods because of the bad behaviors of the other scavengers whom left the garbage scattered in a mess behind them instead of leaving the garbage like it was. | Figure 9. The society acceptance of scavenger work (Source: Field Work 2/10/2010) |

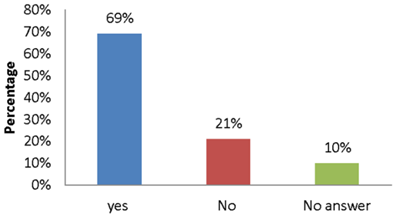

Working with scavengers and integrating them within the SWM system has been identified as a requisite to ensure the success of recycling projects [14]. Most of the scavenger agrees to work under bigger umbrella even if it owned by private sector. However they prefer public sector more. 68% agree to work under municipality umbrella see (figure 10).  | Figure 10. Working under municipality umbrella (Source: Field Work 2/10/2010) |

Organizing of scavenger work under the umbrella of municipalities or private companies can increase their contribution significantly to resource recovery, recycling of waste materials and increase their profits by excluding the agents role form the process.

4. Conclusions

The results show that scavengers in Jordan have an important role in the informal solid waste management especially in term of waste reduction, minimization and material recovery.Significant values from the scavenged material make the scavenging a profitable business for poor people and could track more in the future. Authority does not realize fully the social, economic and environmental benefits of waste recovery process. Instead, they often ignore scavenger opinions in the strategic planning for MSW. Nowadays, there are no official records for the scavenger’s number and the quantity of the recovered material in the country. Scavengers usually have no concept of the essential role their work plays in this process. As a result, their social status is very low. Despite the low level of education for many of the scavengers, the awareness for the negative health effect from working with waste was very high in the cohort. However, usually as they work in a very primitive way without any protective measures for health and safety they could be exposed to hazards which they are not aware of. The scavenging tends to be socially acceptable in the community, especially with the increasing of the poverty rates and employments.The result also relived that scavenger would consider to involve municipalities, private companies and NGOs to work under their umbrellas, as they think it may increase their contribution significantly to resource recovery and increase their profits by excluding the agent’s role form the process. This involving definitely will help to organize integration of scavengers in SWM in a positive way and it will enhance recycling and recovery process. Moreover, to enhance recovering efforts, should decrease the required work for collecting, transportation and final treatment of waste for municipalities. In addition, Industries that accept recyclable materials will encourage and support any organizing efforts in order to assure an adequate volume and quality of the materials. On the other hand, any organization program should consider the social, economic and health of scavengers in a way to help to improve and integrate this sector to enhance recovery process without forgetting that at developing landfills (upgrading to sanitary landfills) scavenging will most probably be prohibited to enter and work at disposal site. Also starting sorting at sources will ban them from streets. As sorting at source of generation is not possible at this time due to socio-economic situation [1], scavenger will continue to be present in Jordan. Programs for teaching them how to perform their work in a health and safety environment should be considered in the organizing and integration process to avoid the high risk of infection and disease transmission which they are not aware of.

References

| [1] | Aljaradin, M., K.M. Persson, and H.I. Al-Itawi, Public Awareness and Willingness for Recycle in Jordan. International Journal of Academic Research, 2011. 3(1 (part II)): p. 508-510. |

| [2] | Nuwayhid, R.Y., et al., The Solid Waste Management Scene in Greater Beirut. Waste Management & Research, 1996. 14(2): p. 171-187. |

| [3] | Wilson, D.C., C. Velis, and C. Cheeseman, Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat International, 2006. 30(4): p. 797-808. |

| [4] | Medina, M., Scavenger cooperatives in Asia and Latin America. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2000. 31(1): p. 51-69. |

| [5] | Daradki, G.A., The Jordanian experience in the management of solid waste. 2008, Corporation for Environmental Protection Arabic report. |

| [6] | METAP, Development of Strategic Framework for Private Sector Participation in MSW Management report. 2008, Ministry of Environment Jordan. |

| [7] | Abu Qdais, H.A., Techno-economic assessment of municipal solid waste management in Jordan. Waste Management, 2007. 27(11): p. 1666-1672. |

| [8] | Wachukwu, C.K., C.A. Mbata and C.U. Nyenke, 2010. The health profile and impact assessment of waste scavengers (rag pickers) in port harcourt, Nigeria. J. Applied Sc, 2010. 1(10): p. 1968-1972. |

| [9] | IPEC, Country Report: The 2007 Child Labour Survey., in Country Report, C.l. statistics, Editor. 2009, International Labour Organization and Department of Statistics of Jordan: Jordan. |

| [10] | Alsrhan, A., Children labor in Algad Daily News Paper. 2006, Algad Amman, Jordan. |

| [11] | Medina, M., The world's scavengers: salvaging for sustainable consumption and production. 2007, Lanham: AltaMira Press. |

| [12] | Thomas hope, E., Solid waste management : critical issues for developing countries. 1998, Kingston: Canoe Press, Univ. of the West Indies. |

| [13] | Aljaradin, M. and K.M. Persson, Design of sanitary landfills in Jordan for sustainable solid waste management. Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 2010. 6(11): p. 1880-1884. |

| [14] | SWEEP, Country Profile on Solid Waste Mangement Situation. 2010, The Regional Solid waste Exchange Information and Expertise Network in Mashreq and Maghreb Countries. |

| [15] | Mrayyan, B. and M.R. Hamdi, Management approaches to integrated solid waste in industrialized zones in Jordan: A case of Zarqa City. Waste Management, 2006. 26(2): p. 195-205. |

| [16] | Haque, A., I.M. Mujtaba, and J.N.B. Bell, A simple model for complex waste recycling scenarios in developing economies. Waste Management, 2000. 20(8): p. 625-631. |

| [17] | V. Femia, P.O.c. Waste and Recycling Behaviors -Do Domestic or Commercial Recycling Programs Raise Awareness and Cause Best Practice. in Twelfth International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium S. Margherita di Pula. 2009. Cagliari, Italy: CISA. |

| [18] | Adeyemi, A.S., J.F. Olorunfemi, and T.O. Adewoye, Waste scavenging in Third World cities: A case study in Ilorin, Nigeria. The Environmentalist, 2001. 21(2): p. 93-96. |

| [19] | Municipalities, M.o. Tafila region Municipalities Report 2010 2010 [cited 2010 15 march]. |

| [20] | Zad, J., Monthly Income for Scavenger in Jordan Zad. 2011, http://jordanzad.com/index.php?page=article&id=49864: amman. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML