-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2014; 4(6): 260-267

doi:10.5923/j.re.20140406.02

Extinction Threat to Tree Species from Firewood Use in the Wake of Electric Power Cuts: A Case Study of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Pride Dube1, Collen Musara2, James Chitamba3, 4

1Department of Environmental Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Ascot, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

2Department of Genetics, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, Free State, Republic of South Africa

3Publishing Department, Zimbabwe Publishing House (ZPH) Publishers, Greendale, Harare, Zimbabwe

4Postgraduate Student, Faculty of Science Education, Bindura University of Science Education, Bindura, Zimbabwe

Correspondence to: Collen Musara, Department of Genetics, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, Free State, Republic of South Africa.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

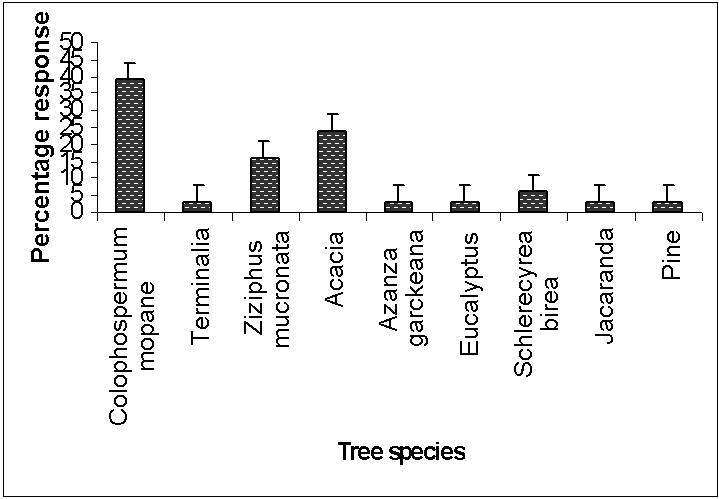

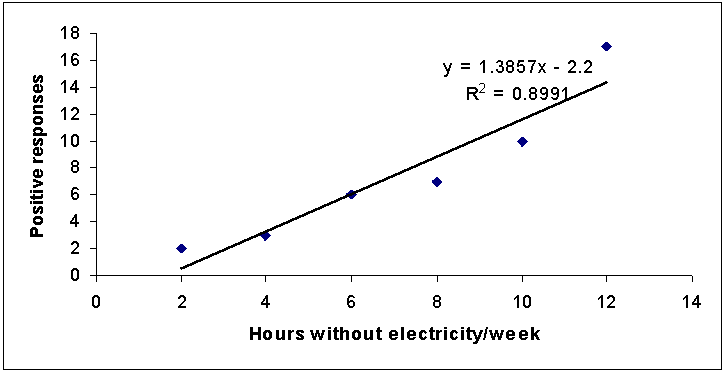

The present study was carried out as a survey to find out the harvesting and consumption patterns of firewood in the wake of electric power cuts that are currently being experienced in the entire Zimbabwean nation. The survey was carried out in Bulawayo and it covered randomly selected high-density and medium- density residential areas. Interviewer-completed and semi-structured questionnaires were administered to residents in the selected residential areas. The average mass of a firewood bundle was measured using a balance. Firewood was found to be the most popular alternative energy source in the absence of electricity (76%), followed by paraffin (10%), gas (7%), jelly fuel (6%) and finally coal (1%). Residents were found to prefer indigenous energy tree species to exotic ones with Colophospermum mopane (39%), Acacias (24%) and Ziziphus mucronata (16%) being the most popular ones while Eucalyptus, Jacaranda and Pine are used in very rare cases. There was significant difference (p<0.05) in mean mass of firewood consumed between high and medium-density suburbs, with the former consuming more (1.79 tonnes per household) than the latter (1.13 tonnes per household). A high positive correlation was also noted between the duration of power cuts and the use of firewood.

Keywords: Firewood, Electric power cuts, High-density area, Medium-density area

Cite this paper: Pride Dube, Collen Musara, James Chitamba, Extinction Threat to Tree Species from Firewood Use in the Wake of Electric Power Cuts: A Case Study of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, Resources and Environment, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 260-267. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20140406.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Energy is a pre-requisite for the proper functioning of nearly all sub-sectors of any economy. It is an essential service whose availability and quality can determine the success or failure of development endeavours. The importance of energy as a sector in any national economy cannot, therefore, be overemphasised. Zimbabwe, after investing heavily in hydro-electricity schemes to alleviate the adverse effects of the oil shocks of the 70’s and early 80’s, is experiencing an energy crisis. Zimbabwe has been experiencing an economic downturn from around 1999. The decline in economic activity during this troubled period led to problems of power generations in Zimbabwe. The power system has been subjected to inadequate and untimely maintenance which was largely due to lack of foreign currency [1].The significance of firewood in the urban energy balance is the limited access to alternative fuels. Firewood competes with other household fuels such as kerosene, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and electricity [2]. The cost of firewood depends among other things on its cost relative to commercial alternatives, their availability and security and supply bottlenecks. These encourage a lucrative black market in which prices are much higher than the official stated prices. The prohibitive costs tend to increase the reliance of poor urban residents on firewood even if it’s scarce and expensive. Besides, there is also the cost of modern cooking appliances, which are not affordable to many households that may want to switch fuels [3]. The dependence of cities on firewood is determined mainly by the access of the residents to alternative, modern fuels like electricity. While urbanisation increases, and urban populations increase, the proportion of urban residents without access to electricity increases. There are many reasons for the high level of utilisation of traditional energy sources in urban areas. Firstly, there is a weak energy infrastructure, which limits the use of modern fuels for, most urban energy needs [4]. Secondly, the supply of modern fuels (especially electricity) is erratic, forcing consumers to revert to the use of traditional fuels at least on a stand-by basis [5]. Thirdly, the low-income levels of the majority of urban dwellers mean that a large proportion cannot afford modern fuels [4].Zimbabwe has two large facilities for the generation of electrical power, the Kariba South Hydropower Station and the Hwange Thermal power Station, but the latter is not capable of using its full capacity due to old age and maintenance problems [6]. There is certainly inadequate power generation capacity in Zimbabwe because Zimbabwe has the potential to generate 1870MW against a backdrop of 2500MW peak demand, of the installed capacity, thereby giving a deficit of 630MW which it has to meet through imports [1]. As a result, the country imports 35% of its power generation from South Africa’s Eskom, Mozambique’s Hydroelectrica Cahora Bassa and the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Snel [7]. The regional power utilities, which were in the first place struggling to supply their own domestic markets as an energy crisis long predicted to hit the region begins to bite, had only guaranteed to supply Zimbabwe with 150MW. Therefore, the economic quagmire in which Zimbabwe has found herself in, with its concomitant high rates of unemployment and very low incomes, has and will continue encouraging the use of firewood in Zimbabwe’s cities. These urban centres have become a lucrative market for firewood because it seems to be relatively available and cheaper than modern (especially electricity) fuels, which hitherto have not proved a viable alternative in urban areas. This growth in demand for wood resources around Zimbabwe’s cities is bound to cause deforestation around the urban centres.Firewood is one of the fuels that contribute towards meeting the energy needs of urban households in Zimbabwe. The use of firewood to supply energy to urban households is a more imminent environmental concern compared to the use of firewood in rural areas. The intensive harvesting of wood to supply urban markets leading to localised impacts [8, 5] is associated with the higher involvement of both urban consumers and traders in the market economy compared to their counterparts. They all act as economic agents, with consumers seeking to maximize utility from energy consumption and traders seeking to maximize profits through selling woodfuels. Thus urban firewood consumption presents a typical linkage between urban economic activity and the environment, in which the consumption needs of urban consumers have implications on the environment, and to some extent, on the tree species extinction. The scenario is made even more peculiar by the fact that the centre of consumption is often separated from the areas of impact. This is different from the rural setting in which woodland resources from which firewood is harvested are part of the immediate surroundings of the consumers, and the impact is evident to the users.As a result, the impacts of firewood harvesting in rural areas are less intense when compared to those in urban areas. This is because; households in rural areas usually do not cut down whole trees, but often collect dead wood, which does not have significant effects on the environment. Harvesting firewood for urban areas on the other hand is intensive on specific areas so as to reduce transport costs. It involves the cutting of whole, live trees and the uprooting of stumps resulting in the loss of entire species and habitat changes in woodland structure and severe soil erosion. The high dependence of urban households in Zimbabwe on firewood has placed pressure on woody biomass resources leading to localized deforestation and land degradation. A few studies have been carried out on urban energy-consumption, especially on firewood. Many researchers focused their attention to rural areas where they thought problems of use of traditional energy sources were more pronounced. For example, a study carried out by the International Centre for Forestry Research (CIFOR) [8] confirmed a decline in the amount of research on woodfuel issues since the late 1980s. For instance, the number of items on firewood or woodfuel listed in the Tree-CD database dropped from a peak of 264 in the period 1982-2986, down to 114 in 1997-2001.Considering this status quo of massive electricity load shedding and its overall impact on the environment in the country, it is against this background that this study seeks to explore the harvesting and consumption patterns and problems associated with firewood use in Bulawayo’s high and medium density residential areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

- The study was carried out in Bulawayo, the second largest city in Zimbabwe, which has an estimated population of 707 000. The area is located in Matabeleland, 439 kilometers south-west of Harare, at an altitude of about 1350 m above sea level and it falls under Natural Region III of Zimbabwe’s Agro-ecological zones receiving an average rainfall of about 564 mm per year. Trees like Acacia spp and Mopane that are adapted to very dry conditions dominate the vegetation of the area.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

- A survey was carried out in four residential areas of Bulawayo’s high and medium-density residential areas, whose houses are connected to electricity. These few residential areas were randomly selected on the assumption that these selected residential areas would be representative of Bulawayo’s high and medium-density residential areas and that their practices, views and opinions would be a fair reflection of the harvesting and consumption patterns of firewood in Bulawayo. High-density (Mabutweni and Entumbane C) and medium-density (Queenspark and Northend) residential areas were selected on the researcher’s personal judgement (judgement sampling) that they experience more electric power cuts than low-density residential areas. Systematic and convenience sampling were used to select the households to be interviewed. The first house in a street or road was interviewed and then the additional households were selected at evenly spaced intervals until the desired number of units (25 per residential area) was obtained.A semi structured questionnaire was designed relating to energy use in the face of electric power cuts, firewood harvesting methods; tree species harvested and source areas and firewood quantities consumed. In any selected residential area, a route or road to be followed by the researcher was selected. Every fifth house was selected and any person found at home was interviewed. The researcher used face-to-face interviews filled in the questionnaires. This was done to increase the response rate, accommodate illiterate people in the survey and to reduce time for data collection. Respondent-completed questionnaires were only used where the respondents were busy when the interviewer visited them so much that he was forced to drop the questionnaires and pick them up later. To ensure expert content and expert validity, the questions were pre-tested on five National University of Science and Technology students and they made some general comments on how best the questions should be improved. Since the questionnaires were mostly interviewer administered ones, it was felt that there was no need to include details on how every question should be answered.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

- The amount of firewood consumed was measured as number of bundles consumed per week per household. The average mass of a bundle was measured using a balance. The amount of firewood consumed per household per week was then calculated by multiplying the number of consumed bundles by the average mass of a bundle. The survey findings were displayed using pie charts, bar graphs and scatter graphs.The data on quantity of firewood consumed was grouped into two groups that is, medium-density and high-density and the data was analysed to assess whether the means of the two groups are statistically different from each other using a one-tailed Student’s t-test at p<0.05 significance level.

3. Results

3.1. Sex and Age of Respondents

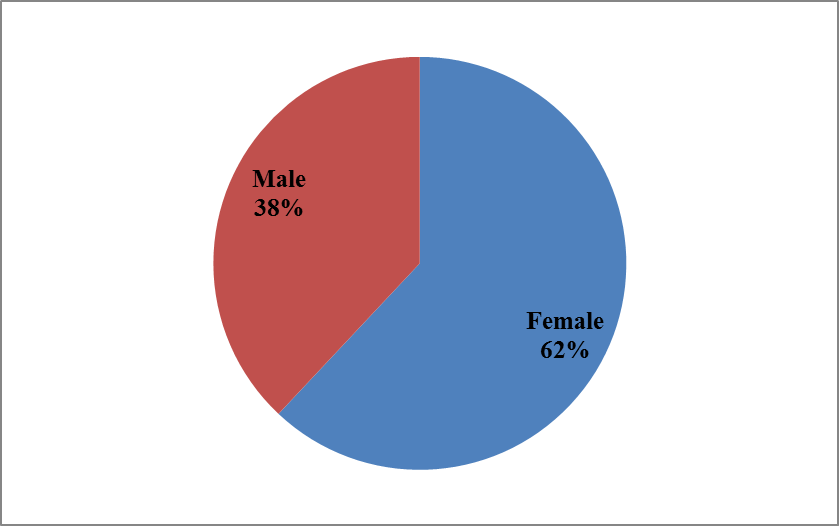

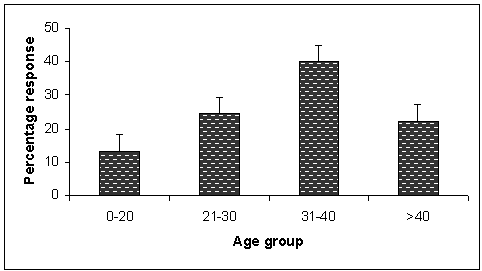

- From the respondents interviewed, 62% were females and 38% were males (Figure 1). Moreover, people of different age groups responded to the questionnaire survey, with the majority falling in the 31-40 years age group (Figure 2).

| Figure 1. Sex of respondents |

| Figure 2. Age of respondents |

3.2. Alternative Energy Sources

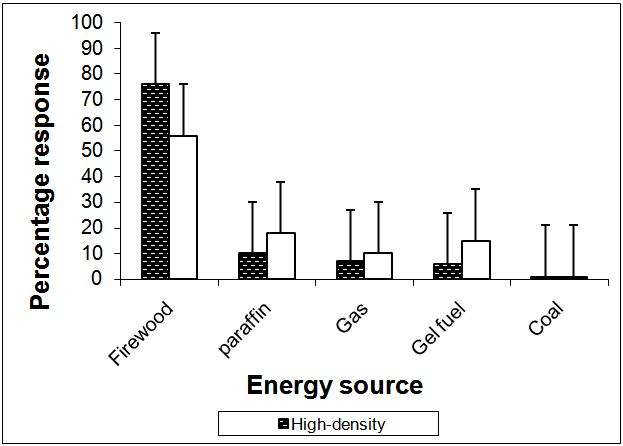

- The survey showed that firewood is the most used energy source for the residents in the face of electric power cuts (76% in high-density and 56% in medium-density areas), followed by paraffin (10% and 15%), gas (7% and 10%), gel fuel (6% and 12%) and finally coal (1%) (Figure 3).

| Figure 3. Alternative energy sources used in Bulawayo’s |

3.3. Methods of Firewood Acquisition

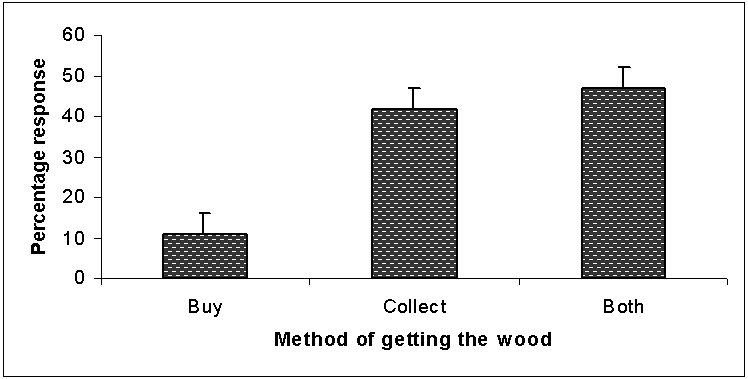

- It was found out that the highest percentage number (46%) of people buy and collect firewood for themselves, 44% collect on their own and do not buy while 10% buy the firewood and do not harvest for themselves (Figure 4).

| Figure 4. Methods of firewood acquisition by Bulawayo residents |

3.4. Tree Species Used for Firewood

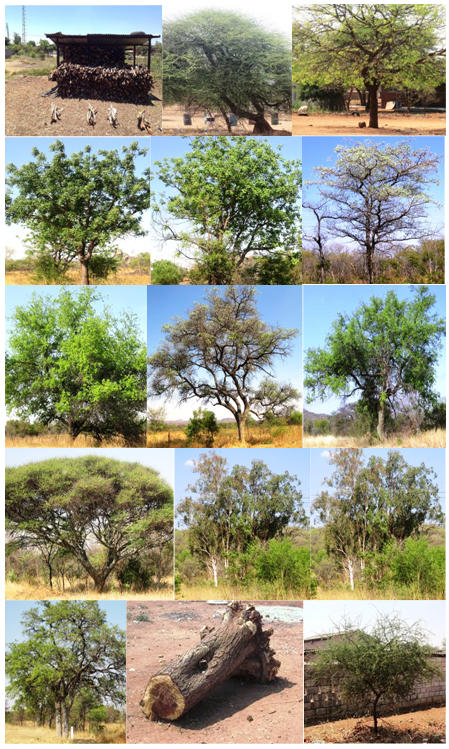

- Colophospermum mopane was the mostly used tree species for firewood followed by Acacia, Ziziphus mucronata and Schlerecyrea birea. However, trees like pine, Jacaranda, Eucalyptus and Azanza garkeana were least used firewood sources (Figure 5a). The photos of some of the tree species used as well as the sample firewood bundles are shown on Figure 5b.

| Figure 5a. Different tree species used for firewood |

| Figure 5b. Different tree species used for firewood |

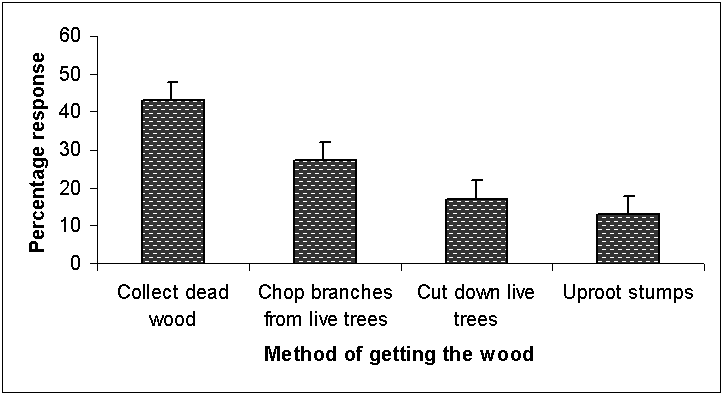

3.5. Firewood Collection Methods

- Most Bulawayo residents get their source of firewood extensively from the collection of dead wood (43%) to the chopping of branches from live trees (27%), cutting down of live trees (17%), the total destruction of tree cover and eventually to the uprooting of stumps (13%), (Figure 6).

| Figure 6. Ways of firewood acquisition by Bulawayo residents |

3.6. Correlation of Blackout Hours and Firewood Use

- There was a strong positive linear relationship between the number of hours without electricity and the use of firewood (positive responses) as shown by the scatter plot diagram (Figure 7).

| Figure 7. Correlation between the number of hours without electricity and the use of firewood (positive responses) |

3.7. Amount of Firewood Consumed

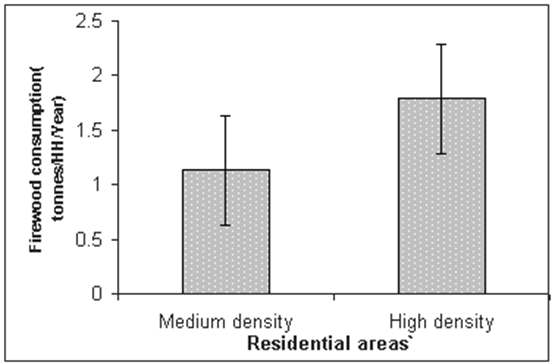

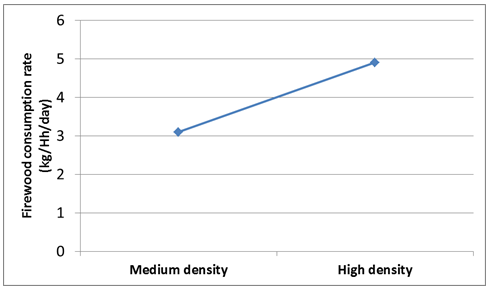

- There was significant difference (p<0.05) in the mean amount of firewood consumed per household between the medium-density and high-density residential areas. The mean amounts of firewood consumed were 1.13 tonnes per household per year and 1.79 tonnes per household per year for medium-density and high-density residential areas respectively (Figure 8a). The firewood consumption rate curve (kg per day per each household) in Bulawayo is shown on Figure 8b.

| Figure 8a. Amounts of firewood consumed in medium and high-density areas |

| Figure 8b. Firewood consumption rate curve |

4. Conclusions

- Firewood was shown to be the major energy alternative for residents in Bulawayo in the face of electric power cuts, because it is easily available and cheaper when compared to other fuels like paraffin and gas. Many residents harvest their own firewood from surrounding areas while others buy from vendors who operate at shopping centres and by the roadsides. Residents prefer indigenous tree species (C. mopane and Acacia spp) to exotic ones (Eucalyptus spp and Jacaranda spp) mainly because of the former’s good burning qualities. Residents employ different methods of harvesting firewood which include the collection of dead wood, cutting of branches from live trees, cutting down trunks and the uprooting of stumps. Residents in low-income (high-density) areas consume higher amounts of firewood than their counterparts in medium-income (medium-density) areas. Increased firewood use might be a threat to the extinction of certain tree species in the study area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors thank the residents of Mabutweni, Entumbane C, Queenspark and Northend residential areas of Bulawayo, Zimbawe, for their cooperation for this study to be successfully carried out.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML