-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2014; 4(3): 162-167

doi:10.5923/j.re.20140403.04

Behavioral Attitudes towards Water Conservation and Re-use among the United States Public

Ellis Adjei Adams

Department of Geography, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48823, United States

Correspondence to: Ellis Adjei Adams, Department of Geography, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, 48823, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Water scarcity is among the most pressing environmental problems of the 21st century. In the United States, almost half of the country is experiencing moderate to extreme droughts with the western part being the most severely hit. Water conservation behavior has emerged as an important solution to water scarcity. While many studies investigated the behavioral aspects of environmental concern, little is known about the links between pro-environmental behavior and water conservation attitude. Using the 2010 General Social Survey (GSS) in the United States, this study answers two questions. First, what is the relationship between socio-economic characteristics and pro-environmental behavior? Second, is there a relationship between pro-environmental behavior and water conservation attitudes? Regression analysis revealed that while socio-economic characteristics did not significantly predict water conservation behavior, pro-environmental behavior emerged as a significant predictor. People who were pro-environmental had greater tendency to conserve water compared to those who were not.

Keywords: Water conservation attitudes, Water scarcity, Environmental concern, Socio-demographic characteristics, Water conservation behaviour

Cite this paper: Ellis Adjei Adams, Behavioral Attitudes towards Water Conservation and Re-use among the United States Public, Resources and Environment, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 162-167. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20140403.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Water is a fundamental natural resource needed for multiple uses such as irrigation, drinking, washing, and cleaning, and also critical to the normal functioning of ecosystems. However, scarcity of this important resource is one of the most pressing environmental problems facing humanity in the 21st century. According to current estimates by the United Nations Joint Monitoring Committee report on water and sanitation, nearly a billion people do not have access to clean water globally while about 2 billion live without adequate and improved sanitation facilities (UN JMP 2013). Freshwater resources are subject to enormous impacts from climate-change, growing per-capita water use in developed and developing countries, and competing uses from diverse sectors-notably agriculture, domestic, and industry. Urbanization and pollution of freshwater resources, coupled with droughts are further aggravating the problem.Current empirical evidence suggests that climate change affect both the quantity and quality of available freshwater resources mainly through reduced groundwater recharge and lowering of water tables (Narayan 1993, Barlage et al. 2002, Mortsch, Alden, and Scheraga 2003, Vincent 2009, Wuebbles, Hayhoe, and Parzen 2010, Shimoda et al. 2011). In the United States, climate change is predicted to affect the hydrology and water resources of the Colorado River basin with implications on hydropower output, river-supported ecosystems, and livelihoods in about seven states (Christensen et al. 2004). The Western United States continues to experience extreme droughts and hot summers with serious consequences for water sustainability. According to a recent white paper released by the Columbia Water Center, major cities along the Great Plains agricultural belt are at risks of water scarcity with serious food-security implications (Columbia Water Center 2013). The report also notes that currently, about 48 percent of contiguous United States is experiencing moderate to extreme drought, and expected to worsen in the future with projected climatic changes. Coupled with this is the alarming growth-rate of per-capita water demand in the United States-an observation which is also a global trend (Gleick et al. 2002, Wade Miller 2006, de Fraiture and Wichelns 2010).The gravity of water scarcity problems across the United States has necessitated the need for alternative solutions, both technological and behavioral. Water conservation through re-use and recycling is emerging as an important avenue through which water can be efficiently used. Behavioral change towards water conservation and re-use, and public acceptance of conservation initiatives remain critical. This study sought to understand whether or not there is any association between people who are environmentally concerned and tendency to conserve water. Although many studies have investigated the links between socio-demographic characteristics and environmental concern, little is known about the relationships between general environmental concern and water conservation behavior. The aim of this paper is to fill this gap by first, investigating the links between socio-economic characteristics and water conservation attitudes, and second, explore whether or not pro-environmental behavior is a predictor of water conservation behavior.

2. Review of Literature

- A lot of scholarship has developed around public attitudes toward the environment (Zelezny, Chua, and Aldrich 2002, Whitmarsh and O'Neill 2010, Welsch and Kühling 2011, Urban and Ščasný 2012). Most of the studies have used sociological and psychological approaches to test attitudes toward the environment, and the socio-economic and demographic indicators that explain environmental attitudes or concern. The New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale is among the most widely used (Christensen et al. 2004, Narayan 1993, Arcury 1990), although there have also been various modifications to the scale (Christensen et al. 2004, La Trobe and Acott 2000, Dunlap and Van Liere 2008). Some of the studies have reported significant relationships between income, gender, and education on environmental attitudes and conservation behavior (Udaya Sekhar 2003, Tonglet, Phillips, and Bates 2004, Gilg and Barr 2006, Timlett and Williams 2008, Sidique, Lupi, and Joshi 2010, Saphores, Ogunseitan, and Shapiro 2012). A plethora of studies have recently tried to understand the factors that drive households to conserve water (Trumbo and O'Keefe 2005, Randolph and Troy 2008, Graymore and Wallis 2010, Willis et al. 2011, Gilbertson, Hurlimann, and Dolnicar 2011, Dolnicar, Hurlimann, and Grün 2012b). Most of the water-conservation behavior studies used direct observations, and (or) asked respondents to self-report their water use behaviors. On the contrary, this study uses the United States General Social Survey (GSS 2010). Hamilton (1983), Berk et al (1993), and De-Oliver (1999) studied the relationships between water conservation behavior and socio-demographic variables such as income, education, and political views. While Berk et al (1993) concluded that income and education have a positive correlation with water conservation attitudes, De-Oliver rather found an inverse relationship. In the United States, political ideology has been found to be a strong predictor of pro environmental behavior (Dunlap and McCright 2008). Conservatives are found to be generally more environmentally concerned than liberals (Cumming 2009). Gender has also been found to be associated with pro-environmental behavior with most of the work predicting that women are more inclined towards environmentally friendly behavior (Stern, Dietz, and Kalof 1993, Dietz, Stern, and Guagnano 1998, Zelezny, Chua, and Aldrich 2002, Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002). From the preceding discussions, it is obvious that demographic and socio-economic factors are good predictors of conservation behavior. The hypotheses for this study were thus informed by the current state of literature. Research on the linkages between pro-environmental behavior and water conservation attitude is underdeveloped. However, a few studies have tried to shed light on the interface between general pro-environmental behavior and water conservation (Willis et al. 2011). Factors such as social norms, knowledge about water conservation, income, education, and household size have emerged as important determinants. Dolnicar, Hurlimann, and Grun (2012a) recently concluded from a literature review that general attitudes toward the environment are important factors that determine water conservation behavior. The important and fundamental question has been to what degree is willingness to take part in pro-environmental behavior a predictor of willingness to conserve water? A study in Australia found that people who generally have positive attitudes toward the environment are also more inclined to conserve water (Willis et al. 2011). In the United Kingdom, Willis et al (2011) sought to understand the relationship between environmental attitudes and urban water use. However, although they found that pro-environmental behavior is associated with less water use, other studies concluded that people who have positive attitudes toward the environment are not necessarily inclined to conserve or use less water (Gilg and Barr 2006). It is obvious from the preceding sections that although there are abundant studies on attitudes that explain pro-environmental behavior, it is not well established that the same factors explain water conservation perceptions and attitudes. This study explores what factors could explain attitudes toward water conservation and re-use, and whether such factors are linked to pro-environmental behavior.

3. Methods

- The central purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships between pro-environmental behavior and attitudes towards water conservation in the United States. I explored if people's perceptions about water conservation are based on socio-demographic factors and general attitudes towards the environment. The study was based on a quantitative analysis of data from the 2010 version of the United States General Social Survey (GSS) using bivariate and multiple linear regressions. The broad question I address is: why do people differ in their attitudes and perceptions toward water conservation and re-use among the United States public. To answer this broad question, the following six related hypotheses were tested in this study.

3.1. Hypotheses (H)

- H1: People with greater levels of environmental concern are more willing to conserve water. H2: Gender differences do not matter in attitudes toward water conservation and reuse. H3: Higher family income is associated with greater willingness to conserve water.H4: Higher level of education is associated with greater willingness to conserve water.H5: Occupation status and age have significant effect on water conservation attitudes.H6: Liberals are significantly more willing to conserve water than conservatives.The dependent variable for this study is the variable (h2oless) based on the question: how often do you choose to save or re-use water for environmental reasons? Respondents were asked to respond to this question on a four-item response scale (always, often, sometimes, and never). The variable is available in ballot 1 and ballot 2 of the GSS. A total of 1419 people responded to the question. In order to avoid missing values, ballot 3 was dropped out of the analysis since it did not contain any respondents. The independent variables were age, gender, education, family income, and occupational status. Gender was dummy coded as 1=female and 0 = male. Both age and years of education was used as continuous variables and not recoded. Total family income was coded into 25 categories based on the midpoint of ranges. Employment status was dummy-coded into (1=employed and 0=unemployed). For this study, three measures of pro-environmental behavior were used to test the relationship between general environmental concern and water conservation attitudes. The first two pro-environmental variables were (recycle) and (energy conservation) that asked respondents about their willingness to recycle and conserve energy respectively. The third pro-environmental behavior variable (willingness to sacrifice for environment-wts) was a scale created from a combination of three variables (grntax, grnprice, and grnsol)1 with an alpha reliability of (α= 0.833).

4. Results

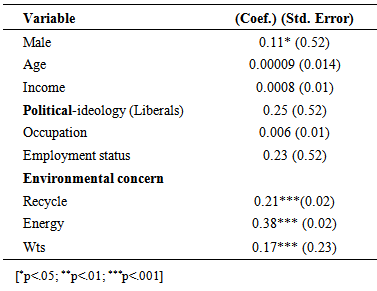

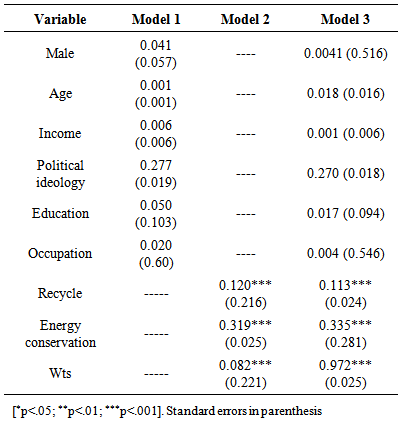

- The details of the bivariate and multiple regressions are presented in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively. Overall, relationships between the dependent variable and 9 independent variables were tested. Out of these, the pro-environmental concern variables (recycle, energy, and wts) showed significant correlations with water conservation attitudes in the bivariate regression. However, with the exception of gender, none of the socio-demographic variables was a significant predictor of water conservation behavior. Income, age, and occupation were not significant predictors of water conservation behavior although listed in the test hypotheses as significant factors. The results show that males are more likely to engage in water conservation behavior than females while liberals were more likely to engage in water conservation behavior than conservatives. This was particularly surprising as females are mostly inclined towards pro-environmental behavior as opposed to males. In the case of the latter, there is ample scholarly evidence that liberals are more pro-environmental compared to conservatives.

|

|

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- This study first investigated the relationships between socio-economic characteristics of the United States public and water conservation. Second, it explored the linkages between pro-environmental behavior and water conservation attitudes. Overall, five related hypotheses were tested to address the research questions. The first hypothesis predicted that people with greater levels of environmental concern will have positive attitudes toward water conservation and re-use. The study found a significant relationship between pro-environmental behavior and water conservation behavior. This finding demonstrates consistency with what other scholars found in Australia where general pro-environmental behavior positively correlated with water conservation behavior (Willis et al. 2011). A plausible explanation may be the fact that generally, people who are pro-environmental also see the need for water conservation, and therefore consider it an important aspect of environmental protection and stewardship. Recycling behavior and willingness to conserve energy were also significant predictors of water conservation attitudes. In other words, individuals who recycle and conserve energy are more willing to conserve water in comparison to individuals who do not engage in recycling and energy conservation behavior. Individuals who have greater measure of willingness to sacrifice for the environment also have the tendency to engage in water conservation behavior. A similar explanation can be offered as the reason why pro-environmental behavior turned out to be a significant predictor of water conservation behavior. Education and income did not show significant influence on the dependent variable. This was contrary to the results of other studies, notably (Berk et al. 1993, De Oliver 1999), who concluded that higher levels of education and income are associated with pro-environmental behavior. Contrary to our hypothesis, political ideology did not emerge as a significant predictor of water conservation behavior although there was a positive correlation. While the relationship was not significant, the correlation is rather the converse of common claims in many studies that liberals are more environmentally friendly compared to conservatives. Gender differences did not emerge as significant predictors of water conservation behavior. This was inconsistent with other scholarly findings that females are more pro-environmental than men (Stern, Dietz, and Kalof 1993, Dietz, Stern, and Guagnano 1998, Zelezny, Chua, and Aldrich 2002, Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002). Overall the results of this study suggest that general pro-environmental behavioral variables are much more important in predicting water conservation behavior than socio- economic variables. Consequently, understanding people’s general attitudes towards the environment can help shed more light on the motivations behind water conservation behavior. The study has contributed to the growing literature on the behavioral aspects of environmental conservation by filling an important gap in literature-the linkages between pro-environmental behavior and water conservation attitudes.

5.1. Policy Implications and Limitations

- As water demands intensify in the United States coupled with climate-related impacts on freshwater resources, effective policies for addressing the growing scarcity are critically important. The findings of this study have practical implications for public engagement in water-conservation policy action. Based on this study, the key factors that drive people to conserve water turned out to be general environmental concern rather than socio-demographic factors as generally posited in the scant water conservation literature. Initiatives that influence people to use less water are critical steps toward water conservation, but must take into account people's general concern about the environment in addition to incorporating our understanding of what socio-demographic factors drive households and individuals to conserve water. This work has moved a step beyond the existing literature and added a new dimension. The first potential limitation of this study is that it was based on an already existing dataset. The researcher did not collect in-person interviews and household surveys. Nonetheless, the data collection procedure for the General Social Survey is intellectually and empirically rigorous, making it a useful data for understanding diverse social phenomena across the United States. Second, the study is solely based on respondents from the United States and may have limited generalizability. Finally, the pro-environmental behavioral variables used (recycling, energy conservation) to create the 'willingness to sacrifice for the environment' scale are not exhaustive, nor are they exclusive. Other measures of pro-environmental behavior may result in different conclusions. Regardless, this study has made an important contribution through cautious interpretation of results based on a general survey across the United States.

Note

- 1. Grntax: willingness to pay higher taxes for the environment. Grnprice: Willingness to pay higher prices for the environment and Grnsol: willingness to accept cuts in standard of living to improve the environment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML