-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2014; 4(1): 67-78

doi:10.5923/j.re.20140401.08

Population Growth and Land Resource Conflicts in Tivland, Nigeria

Fanan Ujoh

Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Fanan Ujoh, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

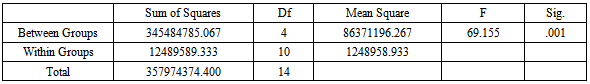

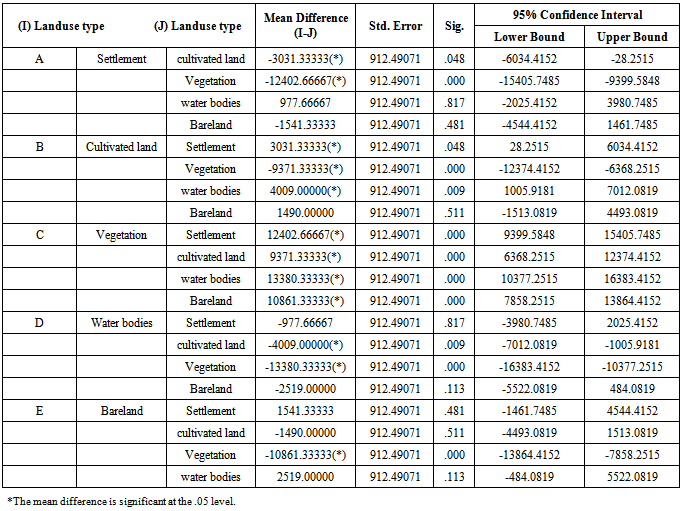

The complex issues of population-resources pressure vis-à-vis communal conflicts in Tivland is the focus of this study. Field interviews and observations were carried out while Census figures for 1953, 1991 and 2006, and Land Use/Land Cover (LU/LC) data of study area for 1987, 1997 and 2007 were used to calculate the Land Consumption Rate (LCR) and Land Absorption Coefficients (LAC). Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Post Hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD test were applied. The results reveal that: (i) greatest increase in LCR (0.019) was recorded between 1987 and 1997 while the later period between 1997 and 2007 recorded a decline in LCR (0.007); (ii) the LAC was greatest between the study periods 1987 – 1997 (0.746) but declined between 1997 and 2007 (0.213); (iii) there is a significant difference between the landuse types studied at the p<.05 level for the 3 ANOVA conditions [F(4, 10) = 69.155, p = 0.001], and as such the assumption that A1 = A2 = A3 = 0 was found untenable. The Post Hoc descriptive mean score for vegetation (M = 13960.3, S.D. = 2085.27) is significantly different from other landuse; (iv) the Post Hoc multiple comparisons reveals that Settlements is inversely related to Cultivated land, Vegetation and Bareland. Also, Water bodies reveal a total inverse relationship with other landuse types, while Bareland exhibits a negative relationship between Cultivated land and Vegetation. Collectively, the results suggest that inter- and intra-communal conflict within the region has a causal relationship with declining per-capita land ownership and scarcity of cultivable land in the face of expanding population. Looking at the complex nature of the problem, the study proposes a multi-disciplinary and systemic approach to reverse the trend, including: (1) periodic research on sustainable agricultural practices; (2) educating the rural populace of the effect of unchecked population expansion on land resources; (3) co-opting communities into stakeholder roles in sustainability programmes and mitigation/adaptation strategies; and, (4) diversification of livelihood sources away from basic subsistence to include other small-scale productive activities through the utilisation of locally sourced resources.

Keywords: Landuse/cover change, Population growth, Communal conflicts, Tivland

Cite this paper: Fanan Ujoh, Population Growth and Land Resource Conflicts in Tivland, Nigeria, Resources and Environment, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 67-78. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20140401.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the major global concerns is the problem of declining land resources that are being threatened by the rapid human population growth, increasing environmental degradation and changing pattern of climate at local and regional levels. There is an increasing need to use resources in a sustainable way; increasing production but at the same time protecting the environment, biodiversity, and global climate systems. This requires careful landuse/resource planning and decision-making at all levels. For instance, several studies[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] reveal rapid changes in Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) in tropical regions in recent decades. Continuous and consistent changes in LULC of tropical regions, often reflecting in terms of intensified land degradation, has major effect on all aspects of the environment. The manifestations of these have been noted to be in the form of rapid disappearance of vegetation cover leading to significant decline in the amount of forestland, soil erosion, soil degradation, huge biodiversity losses, changes in micro-climatic conditions and unfavorable hydrological changes[8], ultimately producing a cause-effect result of conflicts over land and natural resources[9]. High rates of deforestation within a region have been commonly linked to population growth and poorly managed agriculture[1, 10].Recognising the increasing environmental degradation around the globe, the Millennium Declaration in 2000 adapted by 189 countries, which produced the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), sought to present a holistic, multi-disciplinary and multi-dimensional (social, economic, health and environmental) approach to resolving the apparently changing global environment. Of specific interest to this study are:MDG Nos. 1: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, vide:Target 1C – halve the proportion of people who suffer from hunger;MDG No.7: to ensure environmental sustainability, vide:Target 7A - integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programs; reverse loss of environmental resources; and,Target 7B - reduce biodiversity loss, achieving, by 2010, a significant reduction in the rate of loss.The Government of Nigeria has made (and is still making) several efforts towards achieving the MDGs. It is clear that sound natural resource management and planning are essential to tackle the aforementioned problems and to bring about sustainable development[1, 9, 10].

1.1. Nigeria’s Changing Environment

- Ecosystems continuously change and such changes are part and parcel of evolutionary processes. The biggest task for contemporary scientists, in this regard, is to distinguish between this natural decline due to environmental changes and the drastic alterations induced by anthropogenic activities[10]. Nigeria’s changing LULC is reasonably documented as increasing[3, 11, 12]. These changes are products or outcome of prevailing, interacting natural and socio–economic factors[13] and their utilization by man in time and space[14]. LULC change is therefore, central to environmental processes, environmental change and environmental management through its influence on biodiversity, water budget, livelihood[15] peri-urban and rural agricultural land loss[6, 7, 10], and a wide range of socio-economic and ecological processes which on the aggregate affects regional and global environmental change and the biosphere[13].According to Lambin et al.,[1], LULC changes, especially in tropical regions (Nigeria inclusive), are primarily driven by a whole lot of proximate (from local/ direct origins) causes and underlying (from regional or even global origins) causes which cumulatively include natural environmental variability, prevailing economic and technological factors, demographic factors, institutional (political, legal, economic) factors, cultural and traditional factors and globalization. Similarly, continuous modification of the rural environment in Nigeria has been attributed to several human activities such as agricultural colonization and expansion[16], bush burning, fuel wood harvest and over-grazing[17, 18], population expansion[19, 20, 21), and spread of rural settlements and evolution of rural networks[10].Plausibly, the Nigerian rural environment has suffered an accelerating depletion of vegetation, leading to diminishing soil fertility, soil erosion, and increasing severe water scarcity and basic amenities required by increasing human and animal populations. It is in light of these realities that this study is being carried out. With rapid population increase, land degradation and a finite rural land area, available land per individual shrinks pitilessly. Lemmens [22] agrees that “the result is an urgent need for proper geo-management of land and the concomitant availability of a detailed, accurate and up-to-date geo-information”. Predicting how population increase trigger land degradation, the feedback on livelihood strategies from land degradation, and the vulnerability of places and people in the face of the changing environment requires a good understanding of the dynamic human-environment interactions associated with changing land-use[23].It is increasingly becoming clear in recent times that population pressures on natural resources is severely degrading Nigeria’s environment. Poor adaptation to changing environmental conditions is, consequently, inducing reactions such as communal crises and population displacement/mobility in search of more agriculturally viable lands, as is the case with the Tiv rural farming population.

1.2. Research Rationale/Justification

- Historically, humans have increased agricultural output mainly by bringing more land into production. Presently, studies indicate that the amount of suitable land remaining for crops is very limited in most developing nations[24, 25] where most of the growing food demand originates[1]. Much of this growing food demand is located in rural areas. Since rural population has been growing rapidly, particularly in developing countries, land consumption rate has been equally increasing over time which, in turn, has resulted in sustained modification of the land cover and reduction in available and viable agricultural land[6]. The need for increased food production in the study area is reinforced by its constantly increasing population. Land is therefore becoming a scarce resource due to immense agricultural and demographic pressure. Furthermore, a modern society, such as ours, must have adequate information on many complex interrelated aspects of its activities in order to make decisions. This study provides only one such aspect, but knowledge about environmental processes and their outcomes and responses has become increasingly important as the modern society plans and strives to overcome the problems of haphazard, uncontrolled development, deteriorating environmental quality, environmental pollution, loss of prime agricultural lands, destruction of important wetlands, soil erosion and loss of fish and wildlife habitat. Also, studying environmental changes in the North-Central region of Nigeria is essential for analyzing various ecological and developmental consequences over time. This is more so as the region is of environmental, ecological and economic importance, having land cover that is rich in agricultural production, livestock grazing, mineral and natural resources, and a host of other uses such as irrigation agriculture, fishing and so on. Naturally, these land qualities promote agglomeration and population concentration which result in increase in the demand for land in a naturally, ecologically fragile area. Lastly, to understand how environmental change affects and interacts with global earth systems, information is needed on what changes occur, where and when they occur, the rates at which they occur, and the socio-economic and physical factors that drive those changes[26], as well as the impact and responses the changes generate. This study becomes necessary in view of the facts clearly stated above.

1.3. Study Area

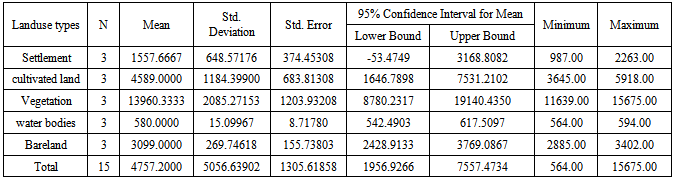

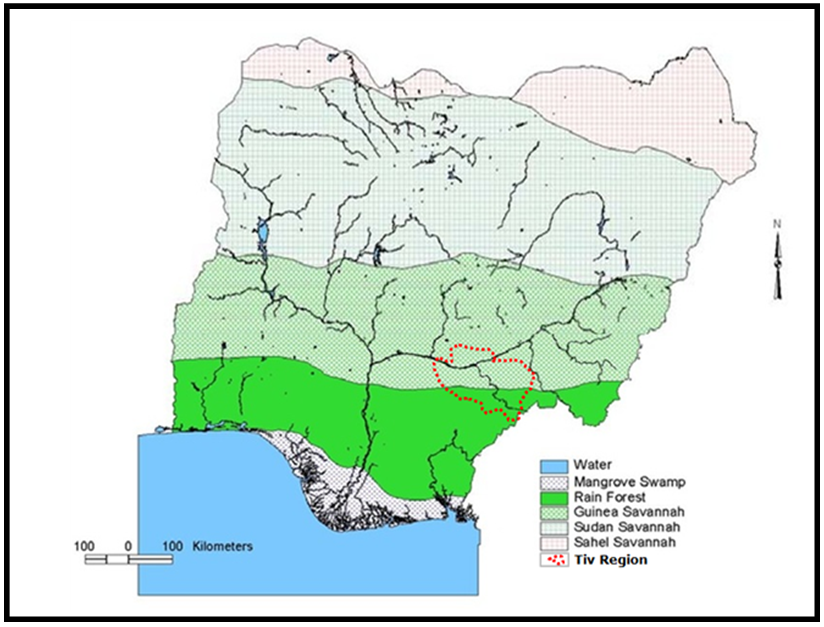

- Historical Background of the Tiv NationAccording to Gundu[27], Tiv are generally considered to be speakers of a “Bantu-related language”. Their early history is however, covered by three theories of origin. These are the ‘Divine Creation’; ‘Bantu’; and, ‘Family’ theories of origin’. The Tiv believe their earliest point of origin is in ‘Swem Karagbe’. Though its exact location is still a matter of debate, a 16th century date derived from the study of Tiv genealogy has been argued for its settlement by[28]. For reasons of over population,[29] and[30, 31] opined that the Tiv left ‘Swem’ and spread in streams of the hills of south eastern present-day Tivland from where they further spread into the middle Benue valley. The Tiv spread from these hills over the Benue plains was propelled by a three pronged attack from ‘Chamba’ tribe on the western banks of the Katsina-Ala River, the eastern banks of the Katsina-Ala River and the western banks of the Donga River. The Tiv victory over the Chamba in these wars enabled them to spread rapidly across the vast Benue flood plain area[28] within which they still occupy to this date. The Tiv are today a dominant group in central Nigeria. Though they are found in large numbers in Nassarawa, Plateau, Taraba and Cross River States, they are mainly in Benue where they are in the majority.LocationAlthough the Tiv are found in several other neighbouring states, the study is focused on the Tiv in Benue state. The Tiv Region in Benue State is located on approximately 80 05”N – 90 45”N and 60 30”E to 80 15”E (Figure 1). The area comprises of 14 Local Government Areas (LGAs). The population of the region is 2,920,481[32], and are pre-occupied in traditional subsistence agriculture/land cultivation and wildlife hunting. As a result of rich alluvial deposits on the Benue’s (and its tributaries’), flood plains, the study area is among the most agriculturally-fertile regions in Nigeria with high agricultural yields produced annually. The Federal Government of Nigeria had christened the state “Food Basket of the Nation” as a result of its capacity to provide a significant food requirement of the nation.

| Figure 1. Location of Tiv Region within Nigeria’s Ecological Zones |

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Environment-Conflict-Population-Mobility Nexus in Nigeria: A Conceptual Framework

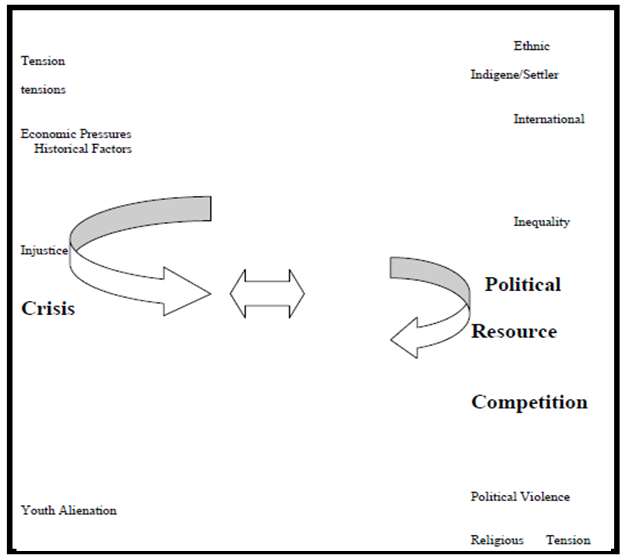

- Generally, contemporary conflicts in Nigeria may be conceptualised as an interaction between political crises (caused by the politics of money and power) and resource competition taking place against a background of various pre-disposing factors. This is diagrammatically presented in Figure 2.

| Figure 2. Background of conflicts in Nigeria (IPCR, 2002) |

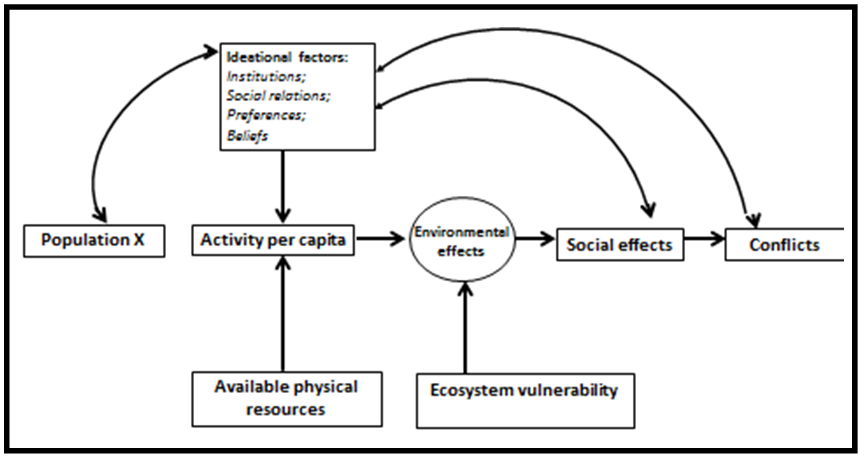

| Figure 3. The Environmental Change and Acute Conflict Nexus (Adapted from Homer-Dixon, 1991) |

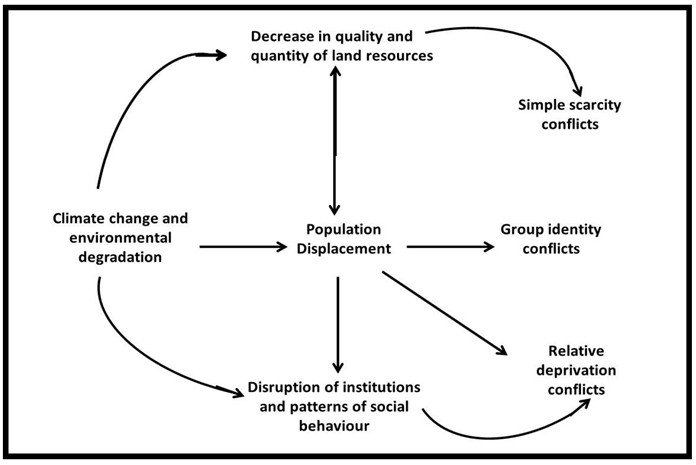

| Figure 4. Types of Conflict likely to emerge from Environmental Change/Degradation (Adapted from Homer-Dixon (1991) and Modified by Author) |

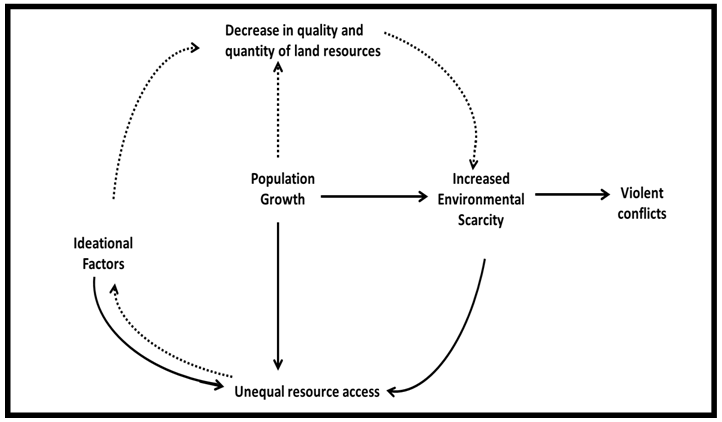

| Figure 5. Resource Capture and Ecological Marginalization in the Process of Violent Conflict (Adapted from Homer-Dixon (1991) and modified by Author) |

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Data and Materials

- LULC data was acquired from classified satellite images of the study area for three epochs (1987, 1997 and 2007) using ILWIS Academic 3.2 software (obtained free online at www.ilwis.com/.) Population data were acquired for the 3 Censuses conducted in Nigeria (1963, 1991 and 2006) from the National Population Commission, Nigeria.

3.2. Data Analysis

- Ground truth exercise (using a Garmin III hand-held GPS unit) and reconnaissance survey were employed to generate training sets and in identifying 5 landuse classes. The Maximum Likelihood Classifier algorithm was used for digital image classification. ILWIS Academic 3.2 software was used for the classification. The data from classified LU/LC of the study area was analyzed within the SPSS Version 15.0 environment for ANOVA test and Post Hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD test. Field visits enabled oral, informal interactions with locals to gain vantage, insightful information on the nature, causes and consequences of intra- and inter-communal migration and communal conflicts in rural areas within Tivland. Also, the Land Consumption Rate (LCR) and Land Absorption Coefficient (LAC) were computed . Lastly, the methodology adapted for estimating and updating the population of the study area was adapted from Zubair[43] using the following function:

| (1) |

| (2) |

4. Results

4.1. Quantification of LU/LC in Tivland (1987, 1997 and 2007)

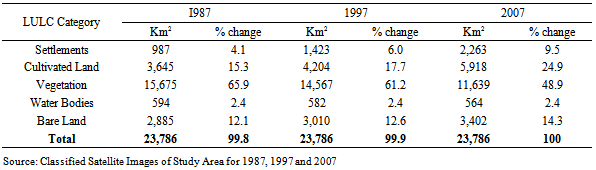

- The classification and quantification of the images of the study area was necessary in the detection of changes in the 5 LULC classes identified. Thus, the static LULC distributions for the study period (Table 1) were derived over the three study years (1987, 1997 and 2007). The results reveal relatively large changes in the ‘within’ and ‘between’ landuse and landcover types (Table 1). Cultivated land has increased by 62.36% over the 20-year study period (Table 2), more than any other landcover category. Contrarily, vegetation has declined by about 34.67% over the same period. Also, bare surfaces have increased by approximately 18%.

|

|

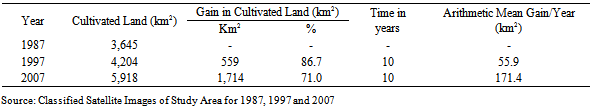

4.2. Population Expansion in Tivland

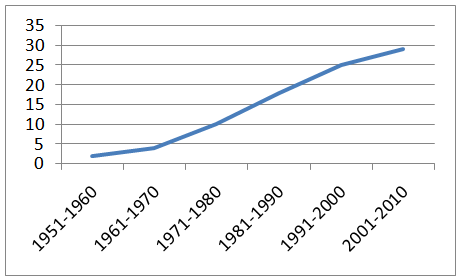

- The population of the study area has increased over time. Table 3 shows the population figures of the Tiv Region in 1963, 1991 and 2006. Between 1963 and 1991 (a period of 28 years), the population increased by 50.1% . However, the increase between 1991 and 2006 (a period of 15 years) is 55.7%, surpassing the earlier increase. The 2006 census puts the population growth rate of the region at 3.0%. Population expansion in the latter period (1991-2006) corresponds with rapid changes experienced in the LULC, and the increased spate of communal conflicts within the area.

|

4.3. Inventory of Land-related Conflicts in Tivland

- Accurate inventorying of land-related communal crises in Tivland may appear challenging due to an overwhelming poor culture of records keeping. However,[44] listed some of the most prominent conflicts in Tivland to include: The 1947 chieftaincy riots in Makurdi, Ushongo - Iharev, Isherev - Utyondu, Tiv - Jukun, Tiv - Udam, Inyambuan, Shoja Patali, Atemtyo, and the militia. Other conflicts include: Ikyurav - Tiev – Kusuv, Ikyurav-Tiev – Shitile, Shangev - Masev, Ipav - Mbayion, Ukan – Mbayion, Tiv - Fulani (45, 46), and a host of many other low-grade conflicts that have not received any media attention. The relevance of the above listed conflicts is based on the fact that they occurred as a mix of intra- and inter-communal disputes starting from 1947 to 2010 triggered by politico-economic factors. The time-path of the occurrence of these conflicts (Figure 6) indicate a rise in the cumulative growth curve as well. The time-path however, computes communal conflicts beginning from 1952 to 2010. Whether inta- or inter- communal, these conflicts “arise from the pursuit of divergent interests, goals and aspirations by individuals and or groups in defined social and physical environments”[9]. Hence, the definition of ‘group’ as regards conflicts in Tivland remains dynamic as clans in Tiv may come together to fight a common enemy (inter-communal) but later fight amongst themselves (intra-communal).

| Figure 6. Cumulative growth curve of communal conflicts in Tivland |

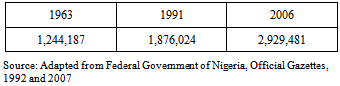

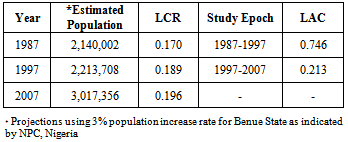

4.4. LCR and LAC of Study Area, 1987, 1997 and 2007

- On the whole, the LCR has consistently increased between 1987 through 1997 to 2007 as shown on Table 4. However, the greatest increase in LCR (0.019) was recorded between 1987 and 1997 while the later period between 1997 and 2007 recorded a decline in LCR (0.007). Similarly, the LAC was greatest between the study periods 1987 – 1997 (0.746) but declined between 1997 and 2007 (0.213) as shown on Table 4.

|

4.5. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

- The F-distribution (probability distribution) function is used to determine how significantly variable the data from classified images within and between the study years are. The goal is to test if data collected from the 1987, 1997 and 2007 are equal (or otherwise), i.e., whether; A1 = A2 = A3 = 0Table 5 shows that there is a significant difference between the landuse types studied at the p<.05 level for the 3 ANOVA conditions[F(4, 10) = 69.155, p = 0.001]. The assumption that A1 = A2 = A3 = 0 is thus, untenable. Similarly, Table 6 reveal that the mean score for vegetation (M = 13960.3, S.D. = 2085.27) landuse is significantly different from the other 4 landuse types. Similarly, the mean scores for cultivated land also differ significantly from water bodies, settlements and bareland. On a whole, there is wide margin of variations among the landuse types.In addition to identifying the landuse types responsive at 0.05 significance level, the Post Hoc multiple comparisons (using the Tukey HSD Test) also provided an interesting insight into the relationship between all landuse types when one serves as a form of control (Table 7). Section ‘A’ reveals that Settlement landuse type has an inverse relationship between Cultivated land, Vegetation and Bareland, while Cultivated land shares an inverse relationship with Vegetation in Section ‘B’ of Table 7. No negative relationship is recorded for section ‘C’. For section ‘D’, the Water bodies landuse shows a total inverse relationship with all other landuse types. This may be explained by the flood regimes often experienced along the plains of River Benue and its tributaries such as Rivers Katsina-Ala, Dura, Amire I, Amire II, etc. within the study area. Lastly, Bareland also exhibits a negative relationship between Cultivated land and Vegetation landuse types. Cumulatively, the three statistically tests results suggest that there is a significant difference between the landuse types observed within the study area. In addition, and quite importantly is the indication that some landuse types decrease as others increase, and vice versa. There is however, the case of converse relationship between some landuse types as clearly revealed by Tables 5, 6 and 7.

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- That shrinking farmlands occasioned by population expansion and unsustainable farm practises are contributing significantly towards the increasing spate of violent intra- and inter-communal conflicts within the study area is a debatable discourse, both within the academia and policy circles. The timings in the decline in LCR and LAC within the study area, the changing landuse pattern observed and the inverse relationship between the landuse classes all together appear to coincide with the period during which communal conflicts and population mobility have been recorded most in Tivland. It may therefore, be plausible to explain rapid population out-migration from conflict hot-spots and population- pressured areas within the Tiv region towards two directions; first is to urban centres within and outside the Tiv region; and, second is to other regions with relative abundance of more fertile and available farmlands. This perhaps explains the presence of the Tiv people found settling in almost all States within the Middle Belt region. This study made efforts to link shrinking per capita land to communal conflicts in Tivland. Therefore, it is hoped that the findings would aid policy framework to the extent that it would be realized that population movements (such as is being experienced in Tivland) can appear as succour in the meantime, but the circle will certainly continue if instructively sustainable and adaptive measures are not put in place sooner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author wishes to acknowledge valuable comments from Dr. O.O. Ifatimehin.

References

| [1] | Lambin, E.F., Geist, J.H. and Lepers. E. (2003) Dynamics of Landuse and Landcover in Tropical Regions. Annual Review of Environmental Resources, 28:205-241. Available On-line at http://www.aginternetwork.net/ Accessed August 3, 2008. |

| [2] | Cohen, B. (2004) Urban Growth in developing Countries: A Review of Current Trends and a Caution Regarding Existing Forecasts. World Development, Vol. 32 (1). |

| [3] | Mashi, S.A. and Alhassan, M.M. (2004) Estimation of Landcover Changes in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Using Satellite Remote Sensing. Proceedings of the 12th Annual National Conference of Environment and Behavior Association of Nigeria. Held at the University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria. 24-26 November. |

| [4] | Fan, F., Weng, Q. and Wang Y. (2007) “Landuse and Landcover Change in Guangzhou, China, from 1998-2003, Based on Landsat TM/ETM+ Imagery”. Sensors, 7. pp 1323-1342. Available On-line athttp://www.mdpi.org/sensors Accessed March 11, 2008. |

| [5] | Njomo, D. (2008) Mapping Deforestation in the Congo Basin Forest Using Multi-Temporal SPOT-VGT Imagery from 2000-2004. EARSeL Proceedings 7, 1. Available On-line at http://www.eproceedings.org/static/vol07_1/07_1_njomo1.pdf?SessionID=49c6647bb6b81ad3fe Accessed July 31, 2008. |

| [6] | Ujoh, F. (2009) Estimating Urban Agricultural Land Loss in Makurdi, Nigeria, Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Unpublished M.Sc Dissertation, Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Abuja, Nigeria |

| [7] | Ujoh, F., Kwabe, I.D. and Ifatimehin, O.O. (2010). “Understanding Urban Sprawl in the Federal Capital City, Abuja: Towards Sustainable Urbanization in Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, Vol. 3, No. 5, pp. 106-113. |

| [8] | Verburg, P.H., Soepboer, W., Veldkamp, A., Limpiada, R., Espaldon, V. and Mastura, S.S.A. (2002) Modelling the Spatial Dynamics of Landuse: The CLUE-S Model. Environmental Management, Vol. 30, No. 3. pp 391-405. Available On-line athttp://www.aginternetwork.net/whalecommwww.sciencedirect.com/whalecom0/ Accessed April 13, 2008. |

| [9] | Obioha, E.E. (2005) Climate Change, Population Drift and Violent Conflicts Over Land Resources in North-Eastern Nigeria. Int’l Workshop on Human Security and Climate Change, Oslo, Norway. June 21-23. Available On-line at http://www.gechs.org/downloads/holmen/obioha.pdf Accessed February 7, 2008. |

| [10] | Muzein, B.S. (2006) Remote Sensing and GIS for Landcover/Landuse Change Detection and Analysis in the Semi-Natural Ecosystem and Agriculture Landscapes of the Central Ethiopian Rift Valley. A Ph.D Thesis Submitted to Technische Universität Dresden, Fakultät Forst- Geo- und Hydrowissenschaften Institut für Photogrammetrie und Fernerkundung. Available On-line athttp://hsss.slub-dresden.de/documents/1173870635741-9841/1173870635741-9841.pdf Accessed July 31, 2008. |

| [11] | Eedy, W. (1997) Overview of the Land Use and Vegetation Change Analysis Study for Nigeria Between 1976 and 1995. Workshop on Land Use and Vegetation Change in Nigeria, 14 May, 1997, Abuja. |

| [12] | Eedy, W. (1999) Land Use and Vegetation Changes in Nigeria: Analysis of Nigerian Environment using Satellite Images and GIS. Proceedings of United States Geological Survey BioGeo99 Conference, 2-4 November, 1999, Lafayette, Louisiana. |

| [13] | Fashona, M.J. and Omojola, A.S. (2005) Climate Change, Human Security and Communal Clashes in Nigeria. Int’l Workshop on Human Security and Climate Change, Oslo, Norway. June 21-23. Available On-line athttp://www.gechs.org/downloads/holmen/fasona_omojola.pdf Accessed February 7, 2008. |

| [14] | Clevers, J., Bartholomeus, H., Müchers, S. and de Witt, A. (2004) Land Cover Classification with the Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS). EARSeL eProceedings 3. |

| [15] | Verburg, P.H., Schot, P., Dijst, M. and Veldkamp, A. (2004) Landuse Change Modelling: Current Practices and Research Priorities. Geo Journal, Vol 51, No., 4. pp 309-324. Available On-line athttp://www.aginternetwork.net/whalecommwww.sciencedirect.com/whalecom0/Accessed April 13, 2008. |

| [16] | Abubakar, S.M. (1999) Assessment of Environmental Changes in Konduga Area of Borno State using Satellite Remote Sensing, GIS and GPS Techniques. THE ENVIRON: Journal of Environmental Studies. Volumes II & III. |

| [17] | Mansour, M.Y. (2006) Wild Fires Deplete Wealth and Harm the Environment. Emirates Fires and Rescue, UAE. Available on-line at http://www.dcd.gov.ae/ Accessed March 24, 2008. |

| [18] | Anavberokhai, O.I. (2007) Mapping Land Use in North-Western Nigeria: A Case Study of Dutse. Unpublished B.Sc Thesis in Geomatics, Department of Technology and Built Environment, University of Gävle, Sweden. |

| [19] | Musaoglu, N., Gurel, M., Ulugtekin, N., Tanik, A. and Seker, D. (2006) Used of Remotely Sensed Data for Analysis of Landuse Change in a highly Urbanized District of Mega-City, Istanbul. Journal of Environ Sci. Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 41 (9) Available On-line athttp://lib.bioinfo.pl/pmid:16849146 Accessed September 22, 2008. |

| [20] | Zubair, A.O. (2006) “Change Detection in Landuse and Landcover of Ilorin and its Environs Using Remote Sensing and GIS, 1972-2005”. M.Sc Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Available On-line at http://www.gisdevelopment.net/thesis Accessed November 20, 2007. |

| [21] | Ujoh, F., Jenkwe, E.D. & Kwabe, I.D. (2010) “Occupational Dislocation and Poverty Levels among the Usuma Dam Communities, Abuja-FCT”. International Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 108-114. |

| [22] | Lemmens, M. (2002) The Survey Triangle. In: Akinyemi, F.O. Mapping Landuse Dynamics at a Regional Scale in South-Western Nigeria. Available On-line at http://www.ipi.uni-hannover.de/fileadmin/institut/pdf/149-akinyemi.pdf Accessed July 31, 2008. |

| [23] | Kasperson, J.X., and Kasperson, R.E. and Turner, B.L. (1995) (eds) Regions at Risk: Comparisons of Threatened Environments. UN University Press, Tokyo. |

| [24] | Young, A. (1999) Is there Really Spare Land? A Critique of Estimates of Available Cultivable Land in Developing Countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 1, 3-18. |

| [25] | Ds, B.R. (2002) Population Growth and Loss of Arable Land. Global Environ. Change: Human Policy Dimensions, 12 (4): 300-311. |

| [26] | Lambin, E.F. (1997) Modelling and Monitoring Landcover Change Processes in Tropical Regions. In: Fan, F., Weng, Q. and Wang Y. (2007) Landuse and Landcover Change in Guangzhou, China, from 1998-2003, Based on Landsat TM/ETM+ Imagery. Sensors, 7. pp 1323-1342. Available On-line at http://www.mdpi.org/sensors Accessed March 11, 2008. |

| [27] | Gundu Z.A. (2001) “Tiv Culture of Death”: Paper presented at 1st National Workshop on Tiv Marriage and Burial Customs, Institute of Management Consultants, Kaduna, Nigeria. |

| [28] | Orkar J. N. (1979) “Precolonial History of the Tiv of Central Nigeria” Ph.D Thesis, University of Dalhousie Canada. |

| [29] | Akiga, S. (1933) Akiga's Story, O.U.P., London. |

| [30] | Gbor JWT (1973) “Tiv Traditions of origin and Migration with Special Emphasis on the Eastern Frontier” B.A. Thesis, ABU Zaria. |

| [31] | Gbor JWT (1978) Mdugh u Tiv Man Mnyer Ve Hen Benue. Gaskiya, Zaria. |

| [32] | National Population Commission (2007). Legal Notice on Publication of the Details of the Breakdown of the National and State Provisional Totals 2006 Census. Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, Vol. 94, No. 24, Government Notice 2. May 15. |

| [33] | Fagbami, A. and Vege-Catalan, F. (1985) An Evaluation of the Physiographic Soil Map of the Benue Valley at Makurdi. ITC Journal; 1985-4: 268-274.http://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/ Accessed April 17, 2008. |

| [34] | Fagbami, A. and Akamigbo, F.O.R. (1986) The Soils of Benue State and their Capabilities. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of Soil Science Society of Nigeria, Makurdi, Nigeria. 6-23. |

| [35] | Pugh, J.C. and Buchanan, Land and People of Nigeria University of K.M. (1955) London, London. |

| [36] | Ojanuga, A.G. and Ekwoanya, M.A. (1994) Temporal Changes in Landuse Pattern in the Benue River Flood Plain and Adjoining Uplands at Makurdi, Nigeria. Available On-line at http://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/ Accessed June 14, 2008. |

| [37] | Wegh, F.S. (1998) Between Continuity and Change-Tiv Concept of Tradition and Modernity, OVC Ltd., Lagos. |

| [38] | Homer-Dixon, T.F. (1991) “On the Threshold: Environmental Changes as Causes of Acute Conflict”. International Security, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 76-116. |

| [39] | Simon, J. (1981). The Ultimate Resource. Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

| [40] | McNicoll, G. (1984) “Consequences of Rapid Population Growth: An Overview and Assessment”, Population and Development Review, Vol. 10, No 2, pp 177-240. |

| [41] | Ehrlich, P. and Ehrlich, A. (1990) The Population Explosion, London. Hutchinson. |

| [42] | Obioha, E. E. (2000) “Ethnic Conflicts and the Problem of Resolution in Contemporary Africa: A Case for African Options and Alternatives”. In P. Nkwi (ed) The Anthropology of Africa: Challenges for the 21st Century. ICASSRT Monograph 2. Pp. 300-307. |

| [43] | Zubair, A.O. (2008) Monitoring the Growth of Settlements in Ilorin, Nigeria (A GIS and Remote Sensing Approach). The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Vol. XXXVII, Part B6b. |

| [44] | Utsaha, APB., Ugbah, S.D. and Evuleocha, S.U. (2007), “The Dynamics of Conflict Management in West Africa: The Case of Violent Conflicts Among the Tiv People of the Middle Belt Region of Nigeria”. Proceedings of the Academy of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, Vol. 12, No. 1. |

| [45] | Aluaigba, M.T. (2008) The Tiv-Jukun Ethnic Conflict and the Citizenship Question in Nigeria. Aminu Kano Centre for Democratic Research and Training, Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria. Available online at http://www.ifra-nigeria.org/IMG/pdf Accessed 11 April, 2012. |

| [46] | Tenuche, M.S. and Ifatimehin, O.O. (2009) Resource Conflict among Farmers and Fulani Herdsmen: Implications for Resource Sustainability. Afri. J. Pol. Sci. Int. Rel. Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 360-364. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML