-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2013; 3(6): 176-182

doi:10.5923/j.re.20130306.02

Situation of and the Rights on the Forest Land, Allocating from the State to Households for Management and Use at the Upland Area in the Central Vietnam

Huynh Van Chuong

University of Agriculture and Forestry, Hue University (Vietnam)102 Phung Hung street, Hue city, Vietnam

Correspondence to: Huynh Van Chuong , University of Agriculture and Forestry, Hue University (Vietnam)102 Phung Hung street, Hue city, Vietnam.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The mountainous area in Phu Vinh commune, Thua Thien Hue province is the typical commune of executing the policy of allocating some areas of poor protection-forest land from the state to households. The purpose of this allocation is to bring many benefits to the society from forest land, to create jobs, to increase forest receivers’ income, and to make the mountain become sustainable. The process of allocating 591ha of forest land state to households in Phu Vinh commune has happened and won villagers’ support. However, research results show that land allocation was delayed, because of governmental policy application and land-allocation procedure are not good. Although governmental policies are quite clear, the rights on allotted forest land have not been specific and macroscopic policies have not been concretized yet. The people, especially the Forest Management Board and local authorities, are still confused in understanding and implementing allocation steps. The villagers are waiting for local authorities to propose very specific land-allocation approaches and land-use plans so that equality can be created and the rights on allocated land can be practiced thanks to forest land certificates. Thanks to that, they can invest in planting forest trees and have stable jobs for regular incomes.

Keywords: Forest Land, Land Allocation, Local Authorities, Management, Rights

Cite this paper: Huynh Van Chuong , Situation of and the Rights on the Forest Land, Allocating from the State to Households for Management and Use at the Upland Area in the Central Vietnam, Resources and Environment, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 176-182. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20130306.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Forest land allocation to households for agricultural and forestry activities has been done for many past years in the whole country (the decree 163/1999/ND-CP). The progress of land and forest allocation in different places is different, among of which that in the mountainous area of the Central Vietnam is slow and encounters many difficulties in comparison with other regions. This is the reason why this research needs to analyze this issue thoroughly. In some researches on this problem, the basic reasons are that the forest land in the Middle has been under governmental management; exploitation and management have been not efficient; villagers have benefited from forest land in the mountain of the Middle mainly by getting forest products and non-forest timber products spontaneously; and villagers have not have as much experience in exploiting and investing money in forest land as agricultural land (Nguyen, 2003). Mountainous residents get accustomed to profiting from forest land by picking up forest products, but they cannot always collect products in large amount. Furthermore, dry rice and cassavas are planted on mountainous fields and forest land for self-consumption and self-supply, not for market. In addition, the investment and the exploitation on forest land need to be done for long time with detailed business plans while most of mountainous residents are poor and have low intellectual standard. As a result, the effective business calculation on forest land is out of their capacity, especially ethnic minorities.The process of forest land allocation from the A Luoi Forest Management Board to households and communities to diversify the managers of land and natural resources still meets many difficulties in terms of policies and management institutions. The rights on this allocated forest land are not clear; there is the confusedness between management organizations before and after allocation. Although the government proposed the rights on forest land as well as agricultural land formally, the understanding and implementing these rights are sometimes different. In addition, the different ethnic groups, living in the mountain of the Central Vietnam, need to be paid attention when land allocation is executed because this issue is related to their habits and benefit-sharing equality.Because of the above reasons, investigating the situation of and the rights on forest land, which have been allocated to households, are very meaningful in discovering the relations and the effects of forest land allocation between the management organizations, being representatives for the government in terms of forest land, and households. What’s more, it is important to find out the difficulties during allocation and proposing solutions to use forest land after allocation effectively.Aims of this study as follows:- Analyzing forest land allocation to households for management and use;- Analyzing informal and formal rights on allocated forest land;- Proposing solutions to facilitate local authorities’ allocation and help them to make the orientations of exploiting land effectively after it is distributed to households.

2. Methodologies

2.1. Approach and Research Framework

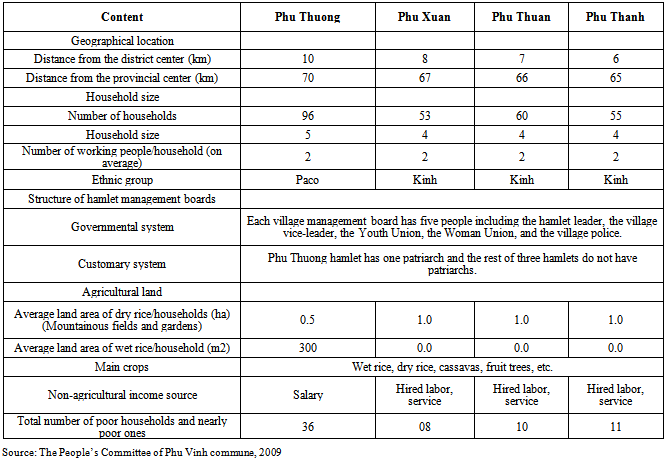

- This research is done by analyzing the rights on the base of the “bundle-of-rights” framework of Mr. Schlager and Ostrom (Schlager, E. and E. Ostrom, 1992). On the base of this framework, the rights on allocated forest land will be analyzed clearly in Phu Vinh commune, A Luoi district. The “Bundle-of-rights” framework is described and adjusted for this research in figure 1.

| Figure 1. “Bundle-of-rights” framework on allocated forest land |

2.2. Methods of Data Collection and Data Processing

2.2.1. Secondary Data Collection

- The researches on forest land allocation to households and communities were collected. Furthermore, the data about the process of land allocation and forest allocation and the rural development programs, implemented in the study site, were gathered. What’s more, the reports, the documents, and the researches related to the policies of land allocation, forest allocation, and the development of agricultural and forestry production at the study site were collected. These documents will serve the surveys and set the base for choosing research samples.

2.2.2. Primary Data Collection

- For quantitative research, the data were collected by interviewing 50 households with the diversification of income-ranking households, household size, ethnic groups, etc. The questionnaire includes households’ characteristics, land-use rights, household groups, and land area. The questionnaire was designed and surveys were done with the support of local governmental officers. Quantitative data were processed by the software SPSS.For qualitative research, group discussions with local governmental officers and villagers were organized. There were three group discussions at each hamlet. Participants were chosen in accordance with different sex classes. What’s more, the in-depth interviews with 10 to 15 households were done in each hamlet.The Global Positioning System was used with the error of +/- 12m to identify the locations of surveyed households and sites.

2.2.3. Data Processing

- In this research, data were processed with synthetical statistics, descriptive statistics, and recurrent analysis to show the changes in land allocation, forest allocation, agricultural and forestry production related to afforestation, cultivation, animal husbandry, and households’ income in these recent years during the process of implementing land-allocation and forest-allocation policies.

|

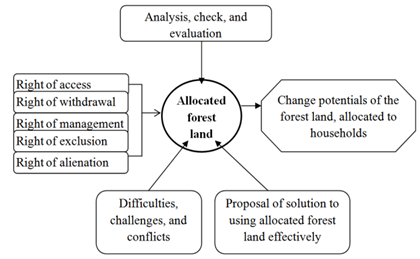

3. Study-Site Description

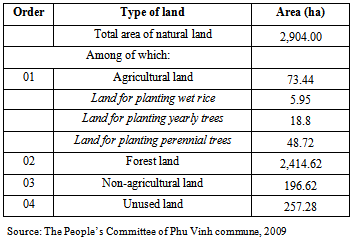

- The study site is Phu Vinh commune, A Luoi district, Thua Thien Hue province, which borders on Hong Phong, Son Thuy, and Hong Quang communes. As shown in table 1, at present, Phu Vinh is one of the poor communes of A Luoi with 60% of poor households. Regarding ethnic groups, Phu Thuong hamlet has 100% of ethnic minorities (Paco people) and Phu Xuan, Phu Thuan, and Phu Thanh have 98% of Kinh people.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Situation of Forest Land Allocation from the Forest Management Board to Households and Influence of Relevant Policies in the Study Site

4.1.1. Situation of the Land Use in Phu Vinh Commune

- The total area, according to the report in 2009 as shown at table 2 and figure 2 is 2,904ha, among of which the land area for agriculture including the area for planting yearly and perennial trees is only 73.44ha; forest area (including fields) is 2,414.42ha; non-agricultural area is 196.92ha, and the rest is unused land with the area of 257.28ha. However, field surveys to identify unused land and the reference to the map with the land administrator Mr. Dang Cao Thieu and the hamlet leaders of Phu Thuong, Phu Xuan, Phu Thuan, and Phu Thanh hamlets show that identifying unused land correctly in accordance with the classification of local authorities and specialized agencies is very difficult. Only a little area of water surface and rocky mountainous land can be seen clearly in reality. Furthermore, local officers and villagers agree that that area cannot be used. Most of the land, including flat land and hilly land, which are supposed to be unused, was reclaimed for growing forest trees and agricultural crops. Therefore, it cannot be considered to be unused land and has no owners as the statistics. This reveals the inconsistence in the name of unused land and the limitation in land surveying and information update, which will cause the difficulties in land management, land planning, and especially land-certificate granting to villagers. Although villagers have reclaimed and used their land from five to ten years, it is still called unused land on document and it belongs to local authorities’ management.

| Figure 2. Appropriation situation for different purposes |

|

4.1.2. Situation of the Forest Land Allocation to Households in Phu Vinh Commune

- According to the household discussions at four hamlets and field observation, the natural resources in Phu Vinh commune such as forest, rivers, streams, ponds, agricultural land, forest land, and deserted land are acknowledged as common properties. Each family’s management, exploitation, and appropriation of the above natural resources are done spontaneously on the base of their customary laws. The voice of patriarchs and family heads is very influential, typically in Phu Thuong hamlet with 100% of ethnic minorities, living here for long time. Most of the old interviewees such as Mr. Ho Van Chien (61 years old), Mr. Ho Van Bay (52 years old), and Mr. Ho Van Dam (59 years old) in Phu Thuong hamlet answered that before 1976, they did not have to follow any governmental policies in exploiting natural resources for livelihoods. People practiced slash-and-burn cultivation and collected forest products. Nevertheless, when the government started to form (after 1976), the common properties on forest land belonged to the state. Collected data show that the land area of the State Forest Enterprise was very big, which occupied over 70% of the total area in Phu Vinh commune. The changes in possession form and forest land management limited natural-resource exploitation, free reclamation, and forest burning for planting dry rice, cassavas, and maize for self consumption and self supply. However, instead of improved after forest was moved to A Luoi Forest Management Board, it was still exploited strongly because villagers lost their common properties according to their own understanding. Therefore, they had to exploit forest stealthily daily. The most typical case was Phu Thuong hamlet with 100% of Paco ethnic minority. They could not change their traditional livelihoods. In addition, the governmental investment in enhancing indigenous people’s capacity of exploiting their gardens was not available at that time. According to field observation and yearly forest-area change, the more the government forbad villagers, the more forest area decreased.Forest loss, the significant decrease of animals and plants, exhausted water source, and the increase of land erosion remarkably affect agricultural and forestry activities and human life. In Phu Xuan, Phu Thuan, and Phu Thanh hamlets, Kinh hamlet leaders and villagers answered that thanks to their will, hard work, and agricultural knowledge from low land, they changed the cultivation approach from shifting cultivation to settled cultivation. In the mean time, ethnic minorities are still confused of earning their new livelihoods because their receipt of technical knowledge is limited because of their weakness in Kinh language; they still depend on the government; they have weaker will and work much less than Kinh people; and they prefer their traditional working methods.Analyzing the policies and the laws of land in general and of agricultural and forestry land in particular in Phu Vinh commune shows that the land law 1993, the decree 64/CP about agricultural-land allocation, and the decree 02/CP, which was replaced with the decree 163/CP about land and forest allocation to households and communities, remarkably change the management and the use of agricultural, forestry, and unused land of the commune. These policies partly help villagers to have the rights of using agricultural and forestry land, which are acknowledged by the state.After the decision 1784/QD.UBND of the People’s Committee of Thua Thien Hue province, A Luoi Forest Management Board will transfer 591ha of production-forest land to the district People’s Committee and then the district People’s Committee will allot this land to households and communities in the near future. Regarding the forest land of 44ha, which is in the process of allocation, the Forest Management Board are transferring this land to the district and the commune for planting agricultural and forest trees. Although there have had no legal decisions and district and commune specialized agencies have not surveyed land and set up landmarks to fix formal boundaries because of the lack of human source and fund, many households fix the boundaries on this land for appropriation by making fences or planting trees. This research will clarify the causes of this phenomenon. However, through investigation and field surveys with local officers, encroachment or argument on appropriated land between households seldom happen. Appropriating the land of the Forest Management Board, which has not been allocated to the commune yet, is popular and happens quite quickly. Villagers appropriate not only this land of 44.8ha but also the land that the Forest Management Board has not transferred to the district yet.According to field surveys, villagers, hamlet leaders, and the commune People’s Committee, in reality, Phu Vinh commune agreed on the land-allocation plan after the Forest Management Board transferred the land of 44.8ha. The priority order of receiving land is the households without productive land, next the poor households, getting governmental allowance in accordance with the decree 134/CP, and finally nearly poor households. Each household receive the maximum land of 1.5ha. That is the right policy, winning villagers’ support. Nevertheless, in reality, when this policy has not been executed yet, 44.8ha was appropriated spontaneously by planting forest trees, digging ponds, and building temporary houses. This appropriation was done on the forest land, not only which was transferred but also which has not transferred yet between governmental agencies. There are many reasons for the above phenomenon: (1) the Forest Management Board do not finish transferring land area at a given moment in accordance with the decision of the People’s Committee of Thua Thien Hue province. The reason is that properties (pine trees) are still on land, so they must be harvested before allocation. Meanwhile, harvest has not finished from 2008 to 2010. (2) The district People’s Committee do not survey land, divide land into plots, and make the plan of growing tress in advance. They do not have strong approaches to push the Forest Management Board to hand over land definitively. They lack financial and technical support to implement the steps of withdrawing and allocating land. (3) The commune People’s Committee does not execute the decisions from higher levels well. They lack human source to carry out the steps of allocating land to households. The commune People’s Committee’s voice is not so strong that villagers dare not appropriate land. (4) The land issue is very sensitive and land can bear benefits; accordingly, every villager wants to have land as much as possible. They try to appropriate land. Villagers’ psychology is occupying land first and they will receive land certificates later. Influenced by many sources of information, they are confused whether they should follow the commune’s instructions while many other people still appropriate land.The forest trees on the appropriated land in Phu Vinh commune include Acacia mangium and indigenous trees, but the growth of these trees are not as good as expectation. The reason is that villagers do not appreciate the economic value of acacias fully. Furthermore, their investment capital in forest trees is very little, which does not provide adequate care for these trees. The another reason is that they try to plant acacias as quickly as possible to appropriate land without thinking whether they can get benefits after 5 years or 7 years. This is also the big difficulty to execute legal procedure correctly. At present, there are no disputes. However, with such present management and slow land allocation from the Forest Management Board and local authorities, they will encounter many difficulties and conflicts will happen between households and households, between households and local authorities because of unfair and unclear allocation. The poor households, who cannot occupy land quickly or the households, who follow local authorities’ direction, will be at disadvantage and for sure, they cannot accept it.

4.2. Analysis of the Rights on the Forest Land, which has been Allocated from the State to Households

- Analyzing and describing the property rights on the study site focus only on two subjects: the state and households because there is no common management of household groups, cooperatives, or communities here.

4.2.1. Right of Access

- When asked about the right of access, most of villagers and governmental officers were surprised at this question because they think that getting access to properties is a matter of course. Instead of being defined in governmental documents, this right is understood tacitly as the legal right for both the state and villagers. For the state, the purposes of this right are surveying land, supervising land, and forbidding people to use land illegally. I asked Mr. Nguyen Van De, the leader of Phu Thuong hamlet, and Mr. Nguyen Van Thieu, the commune land administrator, that whether they regularly got access to villagers’ land to do their management work. They answered that they had this right, but they seldom did this work except there were land conflicts, the orders from higher governmental organizations, or the request for land administrators’ help from the projects at the commune. Remembering villagers’ land is very difficult for land administrators in Phu Vinh while this is the essential condition for commune land administrators’ management.Villagers often get access to their land, others’ land, and the Management Board of Protection Forest’s land. However, this access means that they can only pass by other’s land without damaging and getting the properties on that land. Firstly, if people get these properties, they will be fined very strictly in accordance with customary laws or they have to implement the worship of chickens or pigs for apology. Secondly, local authorities are informed to be involved in conflicts. However, this case has not ever happened in the study site because villagers have high awareness of protecting the properties of each other, according to villagers. At present, villagers approach the land of the Forest Management Board to identify suitable places for appropriation by planting acacias or to exploit properties, especially forest trees. The management on this land is still loose, which creates the chance for people to exploit forest illegally. The Forest Management Board prevents people from illegal activities, but they do not work effectively, which causes illegal access and exploitation on state land to happen more and more strongly.

4.2.2. Right of Withdrawal

- For forest land, villagers have the right of withdrawal after land allocation. The state has not collected tax or any fees on land since 2005. Before, the state levied the tax on land to build the fund for the commune. For villagers, the exploitation for getting benefits on their own land is a matter of course. Each household get different benefit depending on the level of intensive production. Some households can exploit other people’s land in two cases. Firstly, they can borrow other people’s land for getting benefits for one year or two years without paying any expense. Secondly, they have to hire land for some years and return land back to lenders if they are required. In this case, land borrowers have to pay money. If they need very small area of land, they will borrow instead of hiring it. Borrowing land often happens in families. Exploiting unused land can be done for animal husbandry activities, but households are not allowed to use other people’s deserted land for animal husbandry. This is the big limitation for investing money in animal husbandry at present. Many households have capital, but they cannot raise cattle because they do not have deserted land for grazing them.The right of withdraw on forest land is considered as the legal right among nine rights of villagers when they receive land certificates. However, for the forest land, which is going to be allocated in the future, the villagers’ right of withdrawal is illegal. In terms of law, if villagers want to exploit this forest land legally, they have to send request documents to the state. After the state specifies what they can exploit, they can do it. Nevertheless, villagers understand that they have this right as a matter of course. To their understanding, the forest land, which has not been allocated yet, is the common land, so everyone can exploit for livelihoods if they have conditions.

4.2.3. Right of Management

- The right of managing forest land at the state level means surveying and managing land in accordance with state plans. For land survey, management means visiting each agricultural plot. For villagers, they understand that their task is managing their own land. They set up landmarks by making fences or ponds to identify their land boundaries. The right of management is legal right for both the state and households. Yet, in villagers’ awareness, the state’s management does not influence their land use because no one can appropriate their land in accordance with customary laws. Although the state allows them to use their land only for 20 years, to their thought, that land belongs to them and their descendants forever. This thinking is partly legal, but it will cause troubles for the state to revoke land so that this land can be used for other purposes or transferred to other households.

4.2.4. Right of Exclusion

- The state has right of excluding land users from utilizing their land wrongly; for example, they plan forest trees such as acacias on agricultural land or they transfer their land to others without the state’s permission. However, it is very difficult for the state to practice the right of exclusion in Phu Vinh commune because villagers do not inform commune or district authorities when they do the above activities while commune land specialists cannot supervise all happens in reality. Villagers think that they can plant any trees or transfer their land to any people when their land is allocated to them. To solve this problem, in the recent years, in stead of practicing the right of exclusion, the state has popularized land law to villagers. It is the legal right of the state in land management. However, it is very difficult to execute this right in the study site. If it is practiced rigidly, the conflicts between the state and households can occur easily.For households, the right of exclusion comes into effect only when other people appropriate or exploit the properties on owners’ land without owners’ permission. Villagers understand that they have the right of exclusion when the state or some organization withdraws their land without unreasonable compensation. For forest land, which was transferred or in the process of transference, when villagers appropriated this land by setting up landmarks with fences or planting trees at four land corners, they think that they can forbid others’ reclamation or cultivation. In terms of law, this right is informal. Yet, villagers respect this right on the base of customary laws, so few disputes occur. In this way, the right of exclusion is not only formal but informal.

4.2.5. Right of Alienation

- This is one of nine villagers’ rights when they receive land and land certificates, so the state cannot alienate allocated agricultural land. Instead, they only have the right of supervising villagers’ legal alienation.Most of villagers with agricultural and forest land are not aware of the legal right of alienation. However, when they receive land certificates, they think that they can give or exchange their land freely without informing district and commune authorities. Land alienation here is mainly from parents to children. When children get married and live separately, their parents decide to give them some land. Both of them think that that land belongs to children without possessing any documents as evidences or without informing local authorities. Most of the land alienation in the study site is done without the approval of commune and district authorities. The reason is that villagers do not understand land law. Furthermore, villagers assume that the procedure of legal alienation is very complex. It is infeasible because of their low education level. What’s more, inheritance has been done in that way for long time without disputes.For forest and agricultural land, villagers think that they have the rights of alienating and lending their appropriated land without getting commune authorities’ permission. This is the illegal right because that land belongs to the commune People’s Committee, according to the law. If they want to use that land for agricultural and forestry activities, they have to write petitions, which specify the reasons of requesting more land. If they are allowed, they have to use that land correctly in accordance with the commune and the district’s land-use orientations. Nevertheless, this work is only theoretical. In fact, households can exploit land freely. After that, the state formalizes it by surveying land and issuing land certificates.

4.3. Lessons Learnt and Solutions from the Case in Phu Vinh Commune

- The survey on common pool resources and land allocation from the state to households to increase the effect of land use, villagers’ income, the sustainability of resources discovered many issues, similar to other researches’ works in the whole country. However, it found out the specific issues of A Luoi district, Thua Thien Hue province. The above analysis is to affect the policy change in the study site, to help villagers to acknowledge the importance of the policies of using allocated land effectively, and to better the theory of allotting resources to households. Below are some lessons learnt and solutions after this research was implemented.Commune authorities have to execute the macroscopic policies about land and forest allocation thoroughly because this issue is very sensitive, affecting the rights of many subjects, especially the people with the land taken away for re-allocation and land receivers. If not, people may blame each other and finally, villagers will be at the greatest disadvantage because they have to wait.Allocating the land from the state to households must be done comprehensively and follow instructions. Omitting some steps causes the unclearness, the inequality, and the villagers’ doubt in land-distribution approaches, which may lead to disputes and legal proceedings.Surveying land, making the land-allocation plan, and publicizing the land-allocation map and the land-use map must be done before villagers are informed of this issue. If this step is not done, land allocation will not be successful.Discussing with villagers is the decisive condition for making the land-allocation plan. Villagers want to receive more land, but the majority like this work to be done fairly and clearly. Only some people, who appropriate a huge area of land, dislike this approach. If the state gets the consent of the majority, the plan of compensation can be carried out easily.The exemplarity of the powerful people in local authorities in executing the land-allocation policy accurately is very important. If these people did not do appropriation in advance, villagers would not try all ways to do the same thing. When this happens, disputes are unavoidable. If local governmental officers did not appropriate land, local authorities could prevent villagers from this illegal action effectively.Land distributors and land receivers have to discuss the land-allocation approach, which deals with the issues of allocating land in right time and distributing correct land area. Land distributors must not keep land for their rights. Land is the sensitive issue, so stakeholders need to be aware of this problem and think of villagers’ rights.Good strategies to help villagers to use land efficiently after land allotment should be proposed at the same time with land allocation. If only land allocation is done without the clear and feasible land-use plan, land will be used spontaneously and inefficiently. In this way, the meaning of distributing land to households is not as same as planned.

5. Conclusions and Implementations

- The forest land allocation from protective forest management board (representative agency of State) to households locals to the direct management and using for creating livelihood and increasing incomes at Phu Vinh commune in particular and A mountainous areas of Thua Thien Hue (Vietnam) Luoi district in general, still have potential of complicated relationships and meet with some difficulties. Transferred forest land is still seen as common pool resource due to lack of planning, dividing into plots as well as allocating rights address for the users in village, commune. Therefore, encroaching occurs with different encroached area of each household to cause having potential conflicts and contradiction. Forest land allocation so far has not brought benefits to households in the sustainable way yet although the province People’s Committee issued the land-allocation decision two years ago. The macroscopic policy of forest land allocation from the state to households is right, but delay and wrong implementation make villagers misunderstand this policy, which affects villagers’ belief in governmental policies.Local government should have planning and managing for forest land-use after transferring to local people and bring out benefit enjoying policy for local people joined in community explicitly, equitably and long-term stability of at least over 10 years to make the community feel secure on investing and developing production.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to express our gratitude to IDRC’s financial, human, and technical support and the help of CARD in Hue University of Agriculture and Forestry (Vietnam).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML