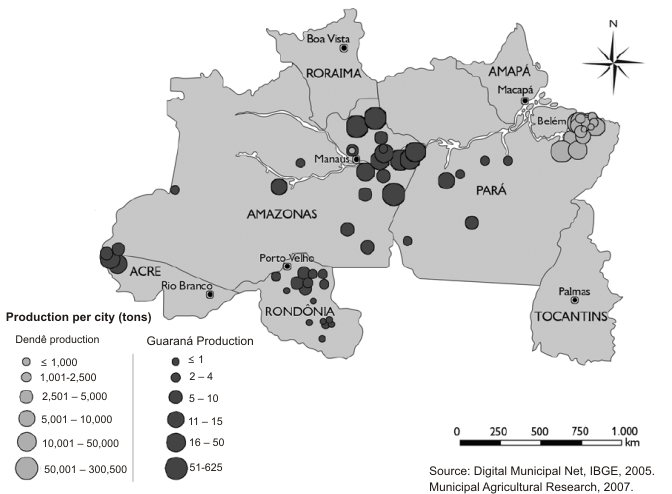

-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2012; 2(6): 253-264

doi: 10.5923/j.re.20120206.02

Community Arrangements, Productive Systems, Scientific and Technological Inputs for Land Use and Forest Resources in Amazon

Wanderley Messias da Costa

University of São Paulo, Geography Department.São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Correspondence to: Wanderley Messias da Costa , University of São Paulo, Geography Department.São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The main focus of this paper is the examination of the current trends in the Brazilian Amazon that is promoting significant changes in the standards of economic use involving some rain forest products. Overall, these new trends are demonstrating an extensive modernization of economic activities that affect specially the structure and dynamics of organized communities in this region. On the other hand, these trends also affect the linkage of these communities and their respective networks. In many cases, the type of region network is led by industrial companies. The research also indicates that the main sources of this new process are the market increase of products extracted in the Amazonian biodiversity and, besides this, both scale and level of processing. Finally, it approaches another strategic source of modernization, represented by a closer and effective participation of regional scientific research institutions in these new or ‘emerging systems’.

Keywords: Forest Products, Timber industry, Emerging systems, New technologies, Land use, Amazon

Cite this paper: Wanderley Messias da Costa , "Community Arrangements, Productive Systems, Scientific and Technological Inputs for Land Use and Forest Resources in Amazon", Resources and Environment, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 253-264. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20120206.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This text has as its main basis a comprehensive research about the themes we develop in the ambit of ProjetoNacional (National Project) for the Development of the Amazon – “Challenges to the Amazon Project”, elaborated together with the Management Center of Strategic Studies (CGEE) in 2008, whose entirety (based on data, charts, graphics and maps) was published in 2009.As a starting point, it is here presumed the general idea that two dominant tendencies persist and coexist as to the forms of work organization and production structures directly related to this modality of forestry resources use.One of these forms relates to numerous and secular modalities of use of these resources by the traditional Amazonian populations,which areorganized under the form of family and/or community work with various ranges of connections with the regional and national markets[1]. These typical systems of the regional Amazonian life are here denominated traditional extractivism. The other, a more recent one, expresses through different forms an ample process of modernization of these activities, by means of which the communities tend to organize themselves in new modalities boosted by productive chains and respective networks led by the bio-industry. In our approach, this connectivity between community organizations and bio-industrial enterprises is denominated ‘emerging productive systems’ (Costa, 2007)[2].Despite the several common aspects regarding these two predominant systems, such as extractivism, the agro-extractivism, the small family production and/or the community organization, a tendency to sharpen the distinction between them has currently been observed; this process is related to the actual growing importance of the second kind of forestry exploration through the combined action of three main vectors. The first is the enlargement and the growing sophistication of the consumption markets in relation to natural products in general, particularly the forestry products, and, especially, those coming from the Amazonian biodiversity. The second is the incorporation of new technologies in all productive chains of these activities, a process which can be basically related to the greater connectivity between Science and Technology (S&T) and Research and Development (R & D) activities of these and other regions with those systems and, additionally, related to new consumption market demands expressed in various mechanisms of self-regulation which have been adopted for quality certification in general and, specifically, the environmental one.The third is associated with more advanced production and integration modalities as well as with the logistics introduced by the big agro-industrial companies – the leading companies – which currently comprise the ‘non-conventional’productive sectors and which have boosted the rapid modernization of forestry extractivism (and also the agro-extractivism) , the family production and the community organization (cooperatives of small producers), especially the bio-industrial systems regarding fruit growing in general, the guaraná production, dende, (non-forestry and forestry) and mainly processed and semi-processed raw material and input destined to phytocosmetic and phytopharmaceutical industries within and outside the region.In order to differentiate the agro-industrial systems, the undertakings here considered as conventional are mainly the ones related to cattle-raising, timber exploration, mining and the cultivation of grains on a large scale (especially soya beans).There are numerous technical documents, produced mainly in the ambit of the Ministry of the Environment /Brazilian Program of Molecular Ecology (MMA/PROBEM) and of the Social Bioamazonian Organization, which concern the potentialities and experiences of the economic use of the Amazonian biodiversity for these industrial segments.

2. Emerging Systems in the Use of Non-Timber Forestproducts

- Recent surveys and studies have in general indicated the dynamism of these systems which, among other characteristics, combine processes of consolidation and expansion of the region and, at the same time, demonstrate other positive aspects (factors, stimuli or vectors) with the potential to promote varied changes in the production circuits and in the life quality of the population,like in the case of the revitalization process of some traditional rural areas of the region characterized by the predominance of the small family production (like in the northeast of Pará) and of riparian nuclei as those located in the lower and middle Amazon/Solimões river (Table 1).They can also be considered an alternative that has been proven efficient to the utilization of deforested, degraded or abandoned areas, especially those associated with the predatory exploration of timber resources or with the failure of great agriculture and animal husbandry enterprises, as, for instance, the various cases of those installed from the fifties, boosted by public policies of rapid acceleration of the region and mainly by tax incentives.In addition, their various modalities of interaction with the (S&T) and (R & D) apparatuses have promoted group mobilizations, networks and research institutions (mainly from the region) and national and state funding agencies, concentrating their focus, most of all, on the general biotechnology applied to agriculture and the sustainable use of biodiversity (cases of genome projects of species or of the development of varieties more resistant to plagues, etc.) whose results contribute strongly to the productivity gainsand to the elevation of quality patterns of processes and products in all the steps of the productive chains of these systems. A vigorous growth process has been registered with diversification of groups and research networks in operation in the region involving various institutions, notably the ones led by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA-EmpresaBrasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária), the Brazilian Institute of Amazonian Research (INPA - InstitutoNacional de Pesquisa da Amazônia.), the Federal University of the State of Pará(UFPA), and the Federal University of the State of Amazonas (UFAM). The above-mentioned genome project, for instance, was developed by a network of researchers created by the National Councilfor Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq-ConselhoNacional deDesenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) and led by a group from UFAM and INPA, which resulted in the genome sequencing of guaraná. Another similar project involving a partnership between EMBRAPA and Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développment (CIRAD, France) is currently dedicated to the genome sequencing of dende.

|

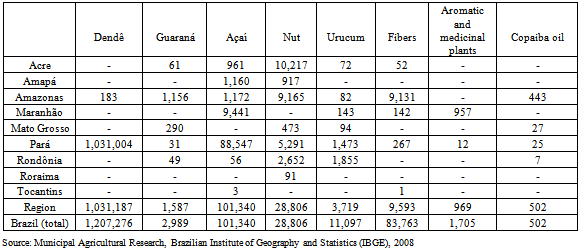

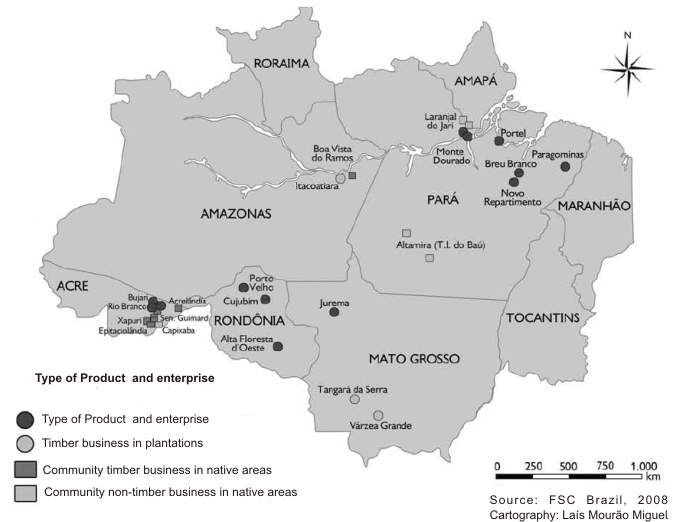

| Figure 1. Examples of community production in the legal Amazon |

3. The Dende Oil Production

- The dende cultivation and the extraction of its oil for different applications constitute nowadays one of the most important agro-industrial activities involved with the production of vegetable oils all over the world. The advantages of dende over other cultures of this kind have been particularly notable, especially in regions of tropical and humid climate, like, for instance, Southeast Asia and Amazon. Several performance indicators attest its superiority over its congeners, particularly soya beans, sunflower and rapeseed. Among other advantages, we can highlight its elevated oil content (around 20%), the relatively simple handling, the short period between planting and starting to harvest (three years, approximately), the high productivity and the endurance of the plants (30 years).Furthermore, it is important to stress its undeniable qualities as a tropical culture destined to the occupation and recuperation of deforested and/or degraded areas, as well as of forestry areas altered in different degrees. This is due to both its capacity to fixate nutrients and to absorb CO2, for example, and to something peculiar about its cultivation, which is the use of vegetable plants in order to protect the soil against invading plants and erosion. In short,besides the economic success, the cultivation of dende is an outstanding means of promoting the biologic recolonization of deforested areas and integrating agro-forestry systems in general. Other advantages of palm oil are associated with its multiple uses by reason of the wide host of derived products and by-products generated by it, both food and non-food items. In the first case, its main uses include frying oil, biscuits, ice-cream, extruded savories, baby food, morning cereals, margarines, dairy products, bread, semi-prepared cakes, vegetable fat, among others. In the field of oleochemistry, its best known application is fuel oil as an improved substitute for diesel fuel. Besides, several of its fractions have been increasingly used as raw material for soaps, for example, and as the base and input for cosmetic, hygiene and cleaning articles, among others.In 2007, the world production of palm oil exceeded, for the first time, that of soya beans oil and the recent expansion of its cultivation to new areas, namely Papua New Guinea and the Brazilian Amazon, indicates that it shall enhance its leading position in this important market. Currently, the two biggest world producers are Indonesia and Malaysia, with approximately 16 million tons/year to each one of these countries, which lead the ranking of the biggest exporters of this product (around 26 million tons/year). In 2006, Malaysia profited US$ 32 billion with the exportation of palm oil and in 2008 it implemented – flowing the example of Brazil – its bio-diesel program, based on vegetable oil, initiating it with the addition of 5% to all the diesel fuel produced in the country.The perspectives of expansion of this cultivation in the Asia-Pacific region for the next years are enormous, currently reaching new producing countries like Papua New Guinea. There is a patent effort in these countries to invest in R&D with a view to elevating the productivity and consolidating the various certification processes of all the productive chain, besides government programs destined to consolidate integrated systems that articulate small family producers’ cooperatives and the big enterprises of the segment. Among these various initiatives, the ones that have been developed in the ambit of Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil should be highlighted (RSPO), a consortium that integrates agro-industrial and industrial companies, rural producers, environmental and social organizations (like World Wildlife Fund–WWF) and governmentrepresentatives at all levels, which have acted intensively to disseminate new practices related to the actual quality demands for processes and products[5].In the Brazilian case, despite the demonstrated potential of Amazon for the dende production in large-scale, this activity is still incipient. As a consequence, the dependence of the country on the external supply of the product has increased in the last years, particularly on refined oil, most used by the industries (importation of 18,3 thousand tons of gross oil and 80,2 thousand tons of refined oil in 2008).

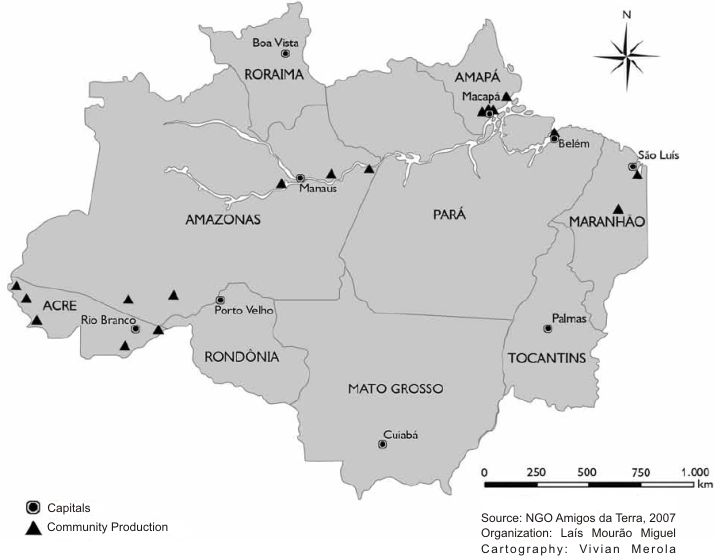

| Figure 2. Guaraná and dende production in 2007 (tons) |

4. The Production of Guaraná Extracts

- The cultivation of guaraná is destined, most of all, to the production of vegetable extract and its concentrated forms which are employed in the production of soft drinks. Currently, its biggest national producer is the state of Bahia (going through a decline nowadays), second only to the states of Amazonas (expanding rapidly) and MatoGrosso. In the state of Amazonas, the production is concentrated in the towns of Maués (most part of it) and PresidenteFigueiredo; it has been developing mainly in integrated systems commanded by leading companies in this sector, like AmBev and Coca-Cola. This activity involves the direct participation of at least two big cooperatives and 12 agricultural centers of small producers in a group of towns of that state, Mauás being in the front line (Barreirinha, Urucará, Boa Vista do Ramos e Parintins).The system works around a bio-industrial center producer of extracts and syrups located in Manaus, whose production is destined almost entirely to the external market and constitutes today one of the principal items of the exports line of the Manaus Industrial Center (PIM). In 2007, around US$131 million in extracts and concentrated of this product were exported, what is equivalent to 12% of the total exportations of PIM. Because of the crisis of its cultivation in Bahia and the productivity gains in Amazon, the potentiality of expansion of these integrated systems in the region is enormous, especially in Amazonas, where new production areas have been incorporated, like PresidenteFigueiredo, which has, in relation to Mauás, advantages with the use of new production technologies and easier accessibility to Manaus. Finally, there has been an increasing tendency to introduce the certification process of this activity in all the productive chain in the last years, including the demand increase – mainly that of the international market – for the so-called organic guaraná.

5. Perpectives of Bioprospection in Amazon

- The actual surveys and studies indicate – by and large – that, despite the virtuous combination of modernizing processes and accelerated expansion, the emerging systems still have not surmounted their original limitations.Regarding the economical use of the typical Amazonian products (native or adapted ones) and their respective agro-industrial and industrial segments, the systems are still restricted to the exploration of species and families of traditional species, not only in fruit growing but also in raw materials and inputs in general for phytocosmetics, for example.Thus, the systems basically keep a special pattern prone to concentration;overall, that is due to their dependence on the availability of conventional (roads, power) and new infrastructure (submarine information highways, for example), besides the density of city networks and the quality of the equipment and services of the urban centers, favoring, hence, the state capitals, especially Belém and Manaus, with their respective networks[7]As these systems have been led exclusively by big-sized private enterprises (national and international), they tend to reflect the limitations imposed by nature and by the objectives of this kind of investment; for example, the fact that the leading companies have demonstrated a scarce (if any) interest in establishing connections of medium and high intensity between the systems and the small undertakings of isolated communities of the deep interior of Brazil, a picture which tends to keep them outside the core area of this modernization, and which has contributed to the reproduction of archaic modalities of collection and/or production and commercialization. Among the big enterprises, the best known are Agropalma (production of dende in Pará), AmBev, Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola (guaranaand its extracts in Amazonas), Crodamazon (essential oils in Amazonas), Brasmazon and Beraca (phytocosmetics in Pará), Natura (inputs and finished products of phytocosmetics and phytoterapeuticals in Amazonas). There is also a diversified group of national enterprises which are headquartered outside the region, but which process and/or manufacture finished productsbased on Amazonian raw material and inputs, destining them to exportation, mainly.Therefore, the action of the State in these circuits is crucial in many aspects, particularly in this case, aiming at disseminating and deepening support programs to the community forest management, like the example of the well-succeeded initiatives of the state governmentssuch as those of Acre, Amazonas and Amapá, mainly the ones from the Federal Government, like the Project of Sustainable Development (PDS-Projeto de DesenvolvimentoSustentável) and the Forest Settlement Project (PAF - Projeto de AssentamentoFlorestal), as approached before. One of the priorities of the “Plano AmazôniaSustentável” (PAS) (Amazonian Sustainable Plan), in its actual version of SECRETARIA DE ASSUNTOS ESTRATÉGICOS.It is necessary to recognize that, despite the actual vigor of the activities of Science, Technology and Innovation (S&T&I) in the region and its positive impacts on the dynamic of those systems, the most effective programs and projects are still, on the whole, concentrated in the products and respective best known segments with the biggest commercial success, namely the cases of guaraná, fruit growing associated or not with the agro-forestry systems (like açaí, cupuaçu, pupunha, etc.), a tendency resulted from some well-known factors, like the insufficiency of investments from the federal government in this area destined to the region (vis-à-vis the others of the country), what is reflected in the limitations of the installed capacity (laboratorial infrastructure, among others) and in the availability and formation of qualified human resources (doctors and post-doctors) for the institutions there located. The main aspects of this picture of deficiencies and the strategic importance of the investments in S&T and R&D for the development of the Amazon in advanced and sustainable bases are very well synthesized in the recently elaborated document by the Brazilian Academy of Sciences – Proposal of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences to a New Development Model for the Amazon (version 05.11.2008), entitled “Amazon: Brazilian Challenge of the XXI Century - The need for a Scientific and Technological Revolution”, in which the amount of investments for the next ten years in this area was estimated in R$ 30 billion, that shall be concentrated mainly in the creation of specialized institutes, in post-graduation programs and the modernization of the institutions of the region[8].Regarding specifically the strategic activities of Research, Development and Innovation (R&D&I) applied to bio-prospection, that is, the process of identifying active principles (with pharmacological or therapeutic potential) obtained from vegetable extracts or animal toxins, and having as its focus the sustainable utilization of the Amazonian biodiversity, the international framework is, under all aspects, less favorable than that of approximately one decade and a half ago. Several programs in this area were created at that time in countries with rich biodiversity – above all, those with tropical forests like Brazil – counting then on the favorable impetus propitiated by the newly instituted Convention for Biological Diversity (CDB - Convenção de DiversidadeBiológica)with a conducive atmosphere for establishing partnerships between the governmental agencies, institutions and research groups and the business sector of this segment.In the Brazilian case, particularly in Amazon, those programs initially concentrated their focus on the development of phytomedicines, having the available scientific literature as their starting point (the biologic inventory, the chemical of natural products and the pharmacological researches) and the wide knowledge of the traditional populations about the so-called medicinal plants, some of them of vast popular mastery. The result of this effort, however, has been practically null so far, especially when related to the development of new natural-based pharmaceuticals or those derived and synthesized from biomolecules and compounds of vegetable or animal origins and that demonstrate economic feasibility , that is, that are tested, approved, certified, patented, licensed and produced in an industrial scale.A well-known group of factors is, to a great extent, responsible for this failure; at least three of them stand out as crucial. Firstly, it has been rapidly found out that it is not enough to possess a rich biodiversity if it is not associated with some concentrated effort of cutting edge researches, that is, which are capable of covering the indispensable steps of bio-prospection that range from the biologic inventory and the selective collection to the patenting and licensing of the product, going through specifically laboratorial stages and clinical trials. After all, the specialists and businessmen of the area know that there are no natural pharmaceuticals strict sensu, but products that require, in general, a long and complex research and development process (from around 5 to 8 years on average) and, therefore, high investments (in some cases they exceed two hundred million dollars), always expecting a very high risk tax (less than 1% of the prototypes become, in effect, pharmaceuticals with commercial feasibility). Secondly, it is indispensable that this research be developed with long and short range goals and by means of the action of various specialist groups strongly engaged and concentrated on obtaining defined results, whichtheycan count on the support of research networks of different sizes and scales. Moreover, the international experience has shown that this is one of the most competitive segments not only of bio-industry but also of the contemporaneous industry in general, currently exhibiting a very strong tendency towards capital concentration and, therefore, widely commanded by the big transnational companies with headquarters in no more than four countries. Thus, they are, for that reason, the only ones that reunite all the conditions for establishing not only market horizons, but also the logistic required for this kind of enterprise, mobilizing massive resources and applying R&D (on average, above 10% of their annual net profit) to the ever more costly stages that comprehend, besides laboratorial researches, clinical trials, the patenting in the international markets (and the further juridical defense of these patents in each country), licensing and marketing.Thirdly, it is widely proven by business and scientific means that, mostly in this globalized phase marked by high competition, the preferential goal of the R&D area of these big companies is changing rapidly. Nowadays it tends to the development of synthetic drugs[9]turned to a relatively small group of therapeutical aims of paramount importance to the populations of a group not superior to five tens of countries, to the detriment of the natural and semi-processed ones, those based on natural compounds or even those derived from them. Furthermore, this actual tendency to exclude products of bio-prospection from the investments portfolio of the big companies of this segment has been ascribed by them as a reaction of the sector to the hindrances presented by some elusiveness of normative and regulatory nature in the so-called ‘mega-biodiverse’ countries and, in some cases, like in Brazil, with the aggravating factor that they can unleash turbulence and damage to their image as a result of mal-succeeded experiences and pioneer projects of this kind. Everything suggests, thus, that the big companies will tend to move away from the so far heralded and promising paths of bio-prospection. This was the case of the polemic involving the attempt to establish a cooperation agreement between the Bio-Amazonia Social Organization and Novartis, which aimed at implementing a bio-prospection project for the development of pharmaceuticals based on the identification of active principles in microorganisms of the Amazonian biodiversity. A similar example is that one related to the insuccess of the partnership between Extrata (National Bio-prospection Company) and GlaxoWellcome, about R&D projects in this area. These projects had as their main support an “Extract Bank” formed from Amazonian vegetable species. In addition, in a recent interview (July, 2008) in “O Estado de São Paulo” Newspaper, the Senior Policy Advisor of the Smithsonian Institute and CDB Consultant, Leonard Hirsch, stressed that the grave problems involving the regulation of this matter, besides the bureaucratic hindrances of all kinds, are factors that must be considered the main responsible for the evident actual disinterest of the companies in R&D projects of new pharmaceuticals based on bio-prospection.In summary, it is necessary to recognize that if the advances in the process of sustainable utilization of the Amazonian biodiversity and of the bioindustry in the area and the production of phytopharmaceuticals and pharmaceuticals depend, like in the other cases, on a strong participation of investments and direct action from the leading companies of the segment, then, in this case, that is not the best of scenarios. In general, the most relevant problems, which tend to break,in the actual conjunction, the full development of the emerging systems in the region can be thus summarized:a) The proven impropriety of the legislation and the various specific federal norms destined to the regulation of the access to the generic patrimony for research purposes and, particularly, for bio-prospection. This picture is aggravated by the actual bureaucratic format, coupled with the obsolescence and the emptyingof the Genetic Heritage Management Council of the Environment Ministry(MMA- Conselho de Gestão do PatrimônioGenético do ministério do MeioAmbiente),what constitutes not only ahindrance to the advancement of the basic researches on the country’s biodiversity, but also a factor that has repelled and nullified,inpractice, any possibilities of investment of the national and international leading companies in R&D projects in this sector. Just by accessing MMA’s site and observing the actual development of this Council one can certifythe gravity of the actual crisis framework.b) The immense quantity and notorious overlapping of laws, decrees, ordinances and resolutionsof organsof federal andstate governments and of specific agencies – like, for example,the National Agency of Sanitary Vigilance (ANVISA - AgênciaNacional de Vigilância Sanitária) –thatnotwithstanding the intention to establish normative mechanisms, regulation and modernization for theseold and new segments in general, have constituted, most of the times, the main hindrance to their development.Under this aspect, it is notorious the inadequacy of legal and technical demands of the management plans in the face of the predominant material conditions of the small forestry enterprises of the region. This is the case of some specific technical norms of ANVISA which arecurrently required for the approval and licensing of products of the cosmetic segment in generalthat call for long, painstaking and costlyprocedures, such as chemical and toxicological testing, among others. What is most emblematic about this kind of hindrance is represented by ANVISA’s set of normscurrently applied to the approval and licensing processes for phytopharmaceuticals, since some of them even include requirementsfor carrying out clinical tests to prove the therapeutical efficacy of these products. Specialists of the area have pointed out thatnorms of this kind may constitute, in practice, an almost unsurmountable barrier to the small industrial enterprises of the country, especially those situated in Amazon. As a consequence, they may contribute to sharpening the process of economic concentration in the strategic market of bio-products. Finally, as indicated above, a considerable share of responsibility for these hindrances as a whole that still break the full development of the bio-industry in Amazon, in particular, must be attributed to the insuccess of the federal programs directed so far to the bio-prospection area. Under this aspect, the actual emptying of PROBEM and the chronic paralysis of the Amazonian Biotechnology Center (CBA - Centro de Biotecnologia da Amazônia), in Manaus, must be taken as emblematic experiences. In the latter case, the picture is the result of, above all, a chronic,institutional, organizational, and operational elusiveness, besides its isolation from national and international research networks of the area and the performance of the leading companies of the segment.

6. Trends, Challenges and Perspective of Forestry Management

- Among the conventional productive systems denominated here, the timber industry in Amazon still constitutes one of the major economic activities of the region, currently employing around 400 thousand people directly, and more than one million under various modalities of participation. Throughout the last three decades, mainly, this evolution may be appraised by means of several indicators,such as the increase in the number of legal and clandestine enterprises (approximately 3.000), the total volume of the timber production in logs (14,6 million of m³) or processed, the enlargement and diversification of the subregions and regions encompassed by this industry (Yared, 2008)[10].Its actual dynamism is basically associated with market growth (national and international) in the segments of raw and processed timberfrom native forests, with the mobility of occupation boundaries, with the thickening and modernization of circulation networks (by road and sea) and, in general, with the expansion of cattle breeding and the agro-industrial activities, especially the cultivation of soya beans.Numerous recent studies demonstrate that, despite the requirements of the environmental legislation in force, like the approval of management plans and the authorizations for the transport, this activity still develops outside the official control systems, operating, mostly, based on archaic systems of exploration with low levels of productivity (great waste of biomass), currently constituting one of the major vectors of environmental impacts on the Amazonian ecosystems. There are very few enterprises of the region that operate in compliance with the legal norms in force and with the procedures required by sustainable or controlled forest management systems, which are adopted internationally in the processes of certification for the segment, currently grouped in the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).In the Brazilian market as a whole, however, there are indications that the demand for certified wood in the consumption markets shows a growth tendency, even thoughrestricted to semi-processed or processed products destined to the international markets. According to FSC, in 2005 there were in the world 689 timber enterprises certified in 61 countries. In 2008, this number turned to 983 enterprises in 79 countries.The transformation industry in this sector, basically concentrated in the South and Southeast, especially the one dedicated to the furniture production and more elaborate artifacts, has currently shown a strong tendency to use certified timber raw materials, but only the ones extracted from planted forests and with species in a slow process of expansion in these regions, like the cases of Pinus andEucalyptus.This increase in the number of certification processes, however, has not still reached the timber production of native forests, like the ones in Amazon. In 2008, the certified production in the region included 26 business and community enterprises, two of them being mixed (timber and non-timber). This number is still blatantly insignificant (less than 1%) when considered the universe of enterprises currently in operation (formal and informal), the total volume of production, the forestry areas encompassed and the scale of regional distribution (Figure 3).Under this aspect, it is patent the isolation of the Amazonian region in relation to the actual and accelerated process of the country’s modernization, not only regarding the more advanced timber sector of other regions (based on planted forests), but also considering the industrial structure in general, since the country occupies the 5th world position in number of certified companies in compliance with the international norms grouped in the FSC.It must be registered, on the other hand, that besides the strong demand for certified timber in the international market and the actual government effort to perfect the control systems over this sector, another vector that has contributed to introducing changes in the segment is associated with the growth of the furniture industry in the region. A specific study on this activity in Paráconcluded that it has played an important role for the modernization of the timber sector in general, as “it is intensive in employment and it helps reduce the environmental impacts of the saw mills, since it uses the wood scraps and residues of these companies as raw materials” (Carvalhoet al., 2007, p. 17)[11]. The authors analyzed the economic development of 84 companies (in a universe of 384). Among the several variables considered, they included some which are not directly economic, like the quality control and the use of technical norms in the productive process, and concluded that 70% is found in what they consider “intermediate stage” as to the general parameters of competitivity.The modernization of this segment is also expressed in the ongoing initiative to implement a Furniture Center in the Industrial District of Manaus, a project that has aroused diverging expectations about its potential impacts on the furniture industry as a whole. In a recent technical document of the Industry Federation of the State of Amazonas (FIEAM - Federação das Indústrias do Estado do Amazonas) about the development of the Manaus Industrial Center (PIM) in 2007, it is stressed that the intensification of control and inspection of the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources(IBAMA - InstitutoBrasileiro do MeioAmbiente e dos RecursosNaturaisRenováveis)and of the state environmental organ, the Amazon Institute of Environmental Protection (IPAAM - Instituto de ProteçãoAmbiental do Amazonas) has caused this industrial segment to rapidly slow down in the last years, as the undertakers would not be able to meet the set of legal and technical norms foreseen in the Forest Management Plans.On the other hand, representatives of small businessmen of this sector claim that the prospective timber center would inevitably promote a concentration process in the market, sinceonly the big enterprises would be able to achieve the investments for big scale industrial plants and, at the same time, operate in compliance with the legal and technical norms that currently regulate this activity.

| Figure 3. Certified forestry areas in the states of the legal Amazon (2008) |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML