-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2012; 2(5): 193-201

doi: 10.5923/j.re.20120205.03

Assessment of Helminths Health Risk Associated with reuse of Raw and Treated Wastewater of the Settat City (Morocco)

K. Hajjami 1, 2, M. M. Ennaji 2, S. Fouad 1, N. Oubrim 1, 2, K. Khallayoune 3, N. Cohen 1

1Laboratory of Microbiology and Food Safety, Pasteur Institute of Morocco. Casablanca, 20100, Morocco

2Laboratory of Virology, Hygiene & Microbiology, Faculty of Sciences & Technics, University HassanII Mohammedia, 20650, Morocco

3Department of Parasitology and parasitic disease, Agronomic and Veterinary Insitute Hassan II, Rabat, 10101, Morocco

Correspondence to: N. Cohen , Laboratory of Microbiology and Food Safety, Pasteur Institute of Morocco. Casablanca, 20100, Morocco.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Settat is an example of Moroccan arid area with severe water scarcity. Wastewater’s agricultural reuse represents a vast potential to remove pressures on freshwater resources of the region. The present study aimed to identify helminth eggs in wastewaters to which both human and animal populations are exposed when they are reused in agriculture and to evaluate removing of those pathogens by Wastewater Treatment Plant lagoons. The technique of concentration adopted for the Helminth eggs research in the wastewaters is that of Arther Fitzgerald and al. The analysis of the results showed that 87.5% of raw wastewater samples and 31.2% of treated wastewater samples are contaminated by the Helminth eggs with a mean concentration of 9 eggs/L and less than 1eggs/L respectively. Helminth eggs found are: Nematodes, Cestodes and several digestive strongyles. Nematodes are mainly represented by Ascaris sp., Toxocara sp and Capillaria sp., for Cestodes, species identified were Hymenolepis nana, Hymenolepis diminuta and Spirometra sp. This study also highlighted the qualitative and quantitative seasonal variations of helminth eggs in wastewater.According to WHO[14], the presence of intestinal nematodes and mainly Ascaris sp, Trichuris and Ancylostoma sp in waste water is considered a major risk for the reuse of water in agriculture. In its new version[43], water reuse guidelines helminth ova are considered one of the main target pollutants to be removed from wastewater reuse for agriculture and aquaculture purposes.

Keywords: Helminths Eggs, Wastewaters, Seasonal Variation, Settat, Morocco

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- With the rapid development of domestic, industrial, and agricultural water supplies, conventional water resources have been seriously depleted. Especially in countries with arid or semi-arid climate, Morocco is one of them and it is now recognized for its significant water stress; (the availability of water varies between 180 m3/inhabitant/year in regions low water content, such as region of Souss Massa, et 1850 m3/inhabitant/year in regions high water content, as the Mediterranean region[1], and moves towards a situation of water scarcity in 2020.The availability of water resources in Morocco is a key factor in the development of the agricultural sector which is the basis of the Moroccan economy; elsewhere, during 1999 and 2000, it declined because a severe drought affected the country leading to a significant decrease in agricultural GDP and stagnation of all Moroccan economy[2].Moreover, farmers in frequent drought areas resort to uncontrolled irrigation by the use of raw wastewater to overcome this lack of water, this practice endangers publichealth and the environment because of the different pathogenic (Bacteria, viruses, parasites, …) that these waters transport[3]; wastewater in fact represent an important vehicle of biological agents[4].Those agents may affect both producers and consumers. The WHO estimates shows that waterborne diseases affect 500 million people per year worldwide[5].Previous studies have reported that parasites, especially helminths exhibit the highest risk of disease transmission associated with the wastewater. This is mainly due to their long persistence in the environment and their low infectious dose ([6],[7]).This parasitological risk has been stated for many decades and then demonstrated by epidemiological studies ([8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13]).In this sense, the WHO described the presence of helminth parasites, particularly intestinal nematodes (Ascaris,Trichuris, Ancylostoma), as the main constraint for the reuse of wastewater in agriculture and recommends for unrestricted irrigation, water containing less than one nematode egg per liter[14].Consequently, the country will face more water shortages, the emergence of serious water-borne diseases and endemic parasites in populations exposed[15].And the government will be forced to face this water challenge wisely: In fact, among the solutions is the wastewater treatment in order to have effluent conform to the standards and guidelines (WHO, FAO) before it is discharged to the nature and reused in agriculture; thereby the risk to public health and environmental impact will be significantly decreased. Especially as these waters are, in addition to the water intake, a source of nutrients up to the suspension of the use of artificial fertilization[16]. In effect, wastewaters are rich in certain nutrients and organic matter such as inorganic nitrogen, organic nitrogen, phosphorus and micronutrients. These are important both to increase fertility and soil structure and agricultural productivity[17].Wastewater treatment plants are usually located on the outskirts of some continental cities where agricultural land is available downstream of effluent spill sites, and in small patches around discharges of sewage. A typical example is the Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) of Settat (Morocco); lagoons Wastewater treatment plants located on the outskirts of the city.Water resources in the region of Settat become increasingly rare and the use of raw wastewater for irrigation of vegetable crops and forage is a common practice. The establishment of the Station has been a means to (i) the protection of water resources (ii) the improvement of hygienic conditions of the surrounding population (iii) Avoid the use of raw wastewater in agriculture without health precaution substitute by treated wastewater[18].Our study focused on the parasitological characterization of wastewater from Waste Water Treatment Plant (WWTP) of Settat and the determination of helminth species present in the wastewater reused in agriculture; which human and animal populations can be exposed. In fact, This work aims to assess:- Parasitological quality wastewater before and after lagoon purification;- The risk associated with the reuse of treated wastewater for agricultural purposes;- The impact of pollution generated by the discharge of raw sewage, on the receiving environment.We propose to make a qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the wastewater’s parasitic load and discuss the variation of helminths’s mean loads encountered during the study period.

2. Study Environment, Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Environment

- Description of the city of Settat:Settat (33°00’N, 7°37’W)[19], is located north-west of Morocco, 60 km south of Casablanca and belong to the region of Chaouia. Its climate is arid to semi-arid. The average annual rainfall is around 400 mm and the average temperature is 25℃ (40℃ in summer and 10℃ in winter)[20]. The city of Settat has 120,000 inhabitants as revealed by the results of the latest census of 2004, produces about 120 tonnes of excrement per day and rejects about 9000 m3 of wastewater per day. Until 2006, this untreated wastewater is reused to irrigate over 400 hectares of agricultural land[21].The sanitation system adopted at the city of Settat is unitary with the exception of the industrial area where the stormwater is discharged through a storm water system independent.Discharges of wastewater from Settat are intercepted by the outfall of wastewater transport and routed to the wastewater treatment plant[22].Description of WWTP (WasteWater Treatment Plant) Settat:The treatment plant is located 8 km north entrance of the Settat city, it covers an area of 80 hectares, it will allow the treatment of flow of 13500 m3 per day, the treated wastewater will be used to irrigate some 300 hectares in the vicinity of that city, a population of around 175 000 people can benefit[18].The treatment of raw water adopted for the station is natural lagoons; the sojourn time for each station is between 40 to 46 days, the first step is screening, then the ponds are arranged and operated in series, with anaerobic ponds (6 units of 0,28 ha each) preceding the facultative ponds (3 units of 5 ha each) which then feed into several maturation ponds.

2.2. Materials and Methods

- We analyzed samples of raw wastewater (taken at the entrance to the station) and treated wastewater (taken out of the station) for a period of two years spanning between January 2009 and December 2010 at a frequency bi monthly, the samples were taken a few inches from the surface. Volumes were analyzed are 1 L for raw wastewater samples and 5 L for treated wastewater samples; it was defined as one giving the most significant results[23]. Given the wide dispersion of parasitic helminth eggs in wastewater, concentration is necessary to ensure a better counting, the samples were then decanted in the laboratory for 24 hours and the sediment recovered (100 to 300 ml) was centrifuged for 15 min at 1000 revolutions min-1.The identification of helminth eggs was carried out at magnifications 100 (in register) after concentration by following the technique of Arther Fitzgerald[24] with the use of Sheater’s solution as flotation liquid. We opted for this technique to its ease of implementation, low cost and risk for the handler and reliability. Microscopic observation of helminth eggs was based on the size, form and content of such eggs in accordance with the bibliographic descriptions. In case we could not identify the species has been limited only to identify gender.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Characterization of the Wastewater Parasitic Load at the Entrance and Exit of the WWTP

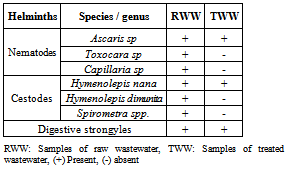

- Parasitological characterization of raw and treated wastewater in the treatment plant allowed us to identify a set of helminth eggs potentially pathogenic for humans and animals can be a cause of helminthiasis. Those eggs belonging to different groups of helminthes parasites: Nematodes and Cestodes and several digestive strongyles (Table 1).

|

3.2. Quantitatative Characterization of Wastewater Parasitic Load at the Entrance and Exit of the WWTP

3.2.1. Seen on the Load Variation in Helminth Eggs: Global Study

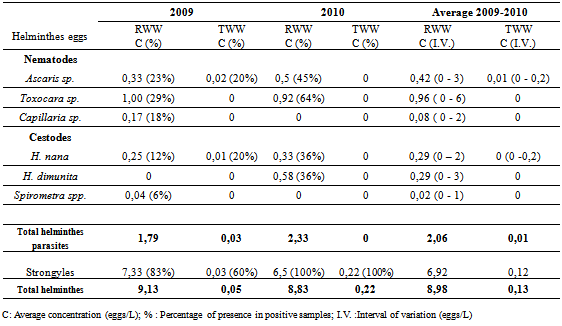

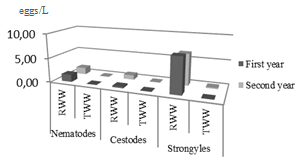

- Parasitological monitoring of wastewater at the entrance and exit of the WWTP shows that raw sewage is contaminated with Helminths eggs with a mean concentration of 9 eggs/L (9.13 eggs/L recorded during the first year and 8.83 eggs/L during the second year). As for the treated wastewater, they have an average load of 0.13 eggs/L (0.05 eggs/L and 0.22 eggs/L during the first and second years respectively) (table 2).

3.2.2. Study by Groups of Helminths

3.2.2.1. Annual Variations

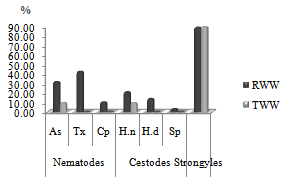

| Figure 4. Average concentration of helminth parasites eggs and strongyles in wastewater at the entrance and exit of the WWTP |

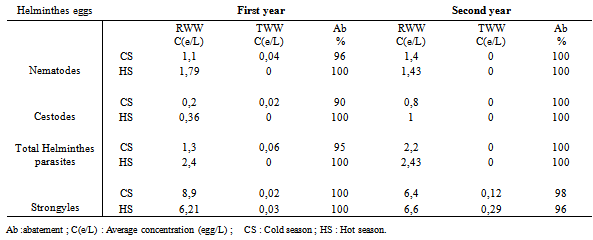

3.2.2.2. Seasonal Variations

- The table 3 shows the seasonal variations in the load of helminth eggs at the entrance and exit of Settat WWTP During the two study periods, it was noted that the analysis of seasonal variations in the load parasitic helminth eggs in raw wastewater showed a slight increase in average concentrations during the hot season (April to October) comparing with the cold season (November to March). The mean concentrations of nematodes during the hot season are 1,79 eggs/L in the first period and 1,43 eggs/L in the second. During the cold season concentrations are 1,1 eggs/L and 1,4 eggs/L, respectively. As for eggs of cestodes whose concentrations are during the hot season of 0,36 eggs/L in the first period and 1 egg/L in the second. During the cold season, these levels fell relatively, they are 0,2 eggs/Land 0,8 eggs/L in the first and second period respectively. In the treated wastewater, nematodes and cestodes were present (slightly) only during the cold season of the first period with concentrations of 0,04 eggs/Land 0,02 eggs/L, respectively. For strongyle eggs, it should be noted that there is a difference in the seasonal variations of the raw wastewater load between the two study periods. During the first period their concentrations are higher during the cold season (8,9 eggs/L) than during the hot season (6,21 eggs/L). During the second period, the load during the hot season is relatively highest (6,4 eggs/L) than during the cold season (6 eggs/L).Regarding treated wastewater, their loads do not exceed 0,29 eggs/L and were lower during the first period.

3.2.3. Study by Species of Helminths

- The parasitological analysis of raw wastewater during the 24 months of the study allowed us to identify helminth eggs with an average concentration of 8.98 eggs/L divided between helminth parasites (23%) and strongyles (77%), this load is lower in purified water: 0,13 eggs/L where strongyles represent 92%.

|

|

- Parasitic helminths eggs detected in this study belong to the class of nematodes and cestodes with the predominance of the first. The class of nematodes is represented by Toxocara sp (0,96 eggs/L), Ascaris sp (0,42 eggs/L) and Capillaria sp (0.08 eggs/L). The one of cestodes by Hymenolepis (0.6 eggs/L) and Spirometra spp. (0.02 eggs/L). Those loads decreased significantly after treatment, it is only during the first period we identified the eggs of Ascaris sp and Hymenolepis nana in 20% of positive samples with concentrations average of 0.02 egg /Land 0.01 eggs/L.The table 4 below summarizes the parasite species identified:

4. Discussion

- In this comprehensive work devoted to the study of parasitological pollution by sewage from the city of Settat and their removal by treatment plant, it was proposed to characterize the parasite load of its wastewater at the entrance (RWW) then the output (TWW) of the WWTP (wastewater treatment plant) lagoons located north of the city.Parasitological examination showed that the average load in helminth eggs is about 9 eggs/L and less than 1 egg/L in raw wastewater and treated respectively. Our results are in the same order than those of Alouini Z. & al.[25], where concentrations are recorded of 2,1 eggs / L, 3 ,1 eggs/L and 3.5 eggs/L in raw wastewater to the WWTP and 0 entries in thewastewater at the exit. The values of the concentration of helminth eggs in raw wastewater in the literature are widely scattered and in some Latin American countries like Brazil an average load of 1490 eggs/L of raw sewage has been reported[26], Jiménez and al.[27] reported an average concentration of 300 eggs/L and 6-98 eggs/L in wastewater from Jordan and Mexico City respectively. In France, lower concentrations (8 eggs/L) were found by Stien and Schwartsbrod[28]. In Tunisia Alouini Z.[29] found average concentrations of 6 to 50 eggs/L, in 2009, higher value (960 eggs/L) was reported by Ben Ayed & al.[ 30]. In Egypt, Stott & al.[31] reported that the concentration of eggs of human intestinal helminths in raw wastewater ranged from 6 to 42 eggs/L.In Morocco, an average concentration of 214,4 eggs/L was observed by Guessab & al.[32] in Agadir. Lower loads were found in Oujda and Meknes, the order of 31.69 eggs/L[33] and 44-36 eggs/L[34] respectively. Then in Ben Slimane, where the average number of helminth eggs in raw wastewater was 23 eggs/L[35].According to some authors, concentrations and varieties of eggs found in wastewater are based on various climatic factors, socio-economic and demographic ([36],[34]) and are closely linked to their origins (domestic water, industrial water, slaughterhouses, stormwater).It is important to note that during their transport from the health network of the city of Settat to the entrance of the WWTP, it would have been an improvement in wastewater parasitological quality that stray particles settle in preferential areas depending on the hydraulic system borrowed ([12],[29]), that finds an explanation in the work of Adam M.[1] where he report that the parameter of importance is the physical characteristic of helminth eggs density. According Bouhoum & al.[37] some parasites can settle more than others, depending on their size and shape, this sedimentation is by their own weight or by adsorption to suspended solids.Kind of parasites present is varied; it is composed of parasites of man and animal. In fact, qualitative analysis identified two groups of helminths in those samples: nematodes and cestodes. This is in agreement with observations of Alouini Z.[29], with a clear predominance for nematodes.This difference is related to the particular population’s lifestyle which eating’s habits (eating meat) do not favor the cestodiasis’s transmission[38]. In addition, Schwartzbrod & al.[39]; Bouhoum and al.[36]; Alouni and al.,[25] and Guessab & al.,[30] reported that the eggs of the class of intestinal Nematodes are stronger than those of Cestodes in wastewater.Helminth eggs identified are represented by the following species: Ascaris sp, Toxocara sp and Capillaria sp, for the class of nematodes and Hymenolepis sp and Spirometra spp. for the class of cestodes but with a large presence of digestive strongyle eggs compared to species of helminth parasites, we note that the presence of the latter depends to a large extent of releases of the city slaughterhouse.Several other authors have found some of these species in wastewater at varying concentrations ([40],[41][42]); Klutse.& Baleux[42] find an average of 4 eggs/L and less than 1 egg/L of Ascaris in raw and treated wastewater respectively . Moreover, Ascaris and Hymenolepis helminths are most associated with raw sewage[21].The analysis of seasonal variations in levels of helminth eggs in raw wastewater showed that the average concentration of parasites helminth eggs is slightly higher during the hot season compared with that seen during the cold season. By cons, we found higher levels of strongyle eggs in the cold season than during the hot season of the first period of the study, this result concurs with that of Habbari[9] in Marrakech; Chalabi[44] to Rabat, of Dssouli & al.,[16] and Mrabet[38] in Oujda; Amahmid. & al.,[45] and Bouhoum and al.,[46] in Marrakech, Naour[45] in Beni-Mellal and El Guamri & al. at Kenitra[48]. Several authors have reported that the concentration difference between these two periods is due to the increased prevalence of parasitic worms (verminosis) in Spring ([48],[49],[50]). While the WHO[14] reported that the abundance of helminth eggs in hot weather is due to conditions of temperature, humidity, oxygen and sunlight favor the maturation of these helminths.As for the abundance of strongyle eggs in the cold season, it is explained by the fact that the digestive strongyles have a seasonal pattern; infestations are particularly rainy season due to the high sensitivity of infective larvae of strongyles on drying[48].The result on the variation of the mean strongyle eggs in the second period was different from that observed during the first, the average concentration of strongyle eggs in the cold season was lower than that recorded during the first year and slightly lower than that recorded during the hot season. The influence of climatic variations on the wastewater quality was emphasized by several authors. Rainfall would then play a role in the variation of the sewage load where it could fall as a result of dilution with rain water; the average rainfall in the region of Settat have increased comparing 2009 to 2010, they were respectively 37,7 mm and 47,7 mm[51]. Especially since the year 2010 marked periods of unusually high rainfall that occurred to cause flooding in various parts of the kingdom, with the goal of good management of the WWTP and control of the flow entry of water, the course of wastewater from certain parts of the city of settat (including rain water) can be deflected out of the STEP (towards the natural environment: Oued Boumoussa[22] where storm or when the inlet flow rate recorded at the entrance of the WWTP is greater than five times the normal rate. Thus, the charge arriving at the WWTP would be in one hand due to the deviation from the path of wastewater and in another hand diluted by rainfall know that the cold season.Helminth parasites found in these wastewaters have a simple life cycle and are able to cause infection through wastewater ([52],[34]). Studies in different countries by IWMI (International Water Management Institute) ([53],[54]) have served to highlight the impact of these practices irrigation on the environment and health. Bouhoum[6] had identified cases of helminthiasis in an epidemiological study of intestinal helminths in children's area of application of sewage Marrakech and concluded that the risk attributable to the use of wastewater in the transmission of helminths was 22%. Kettani S.[55] reported from a study, about Intestinal parasitosis and use of untreated wastewater for agriculture in Settat, that prevalence of Intestinal parasitosis in population exposed to agricultural reuse of wastewater was significantly higher than in the unexposed group(66.4% against 31.9%) where Ascardiose showed a prevalence of 4.2% and 0% respectively. The exposed group is represented by the inhabitants of a village that northern settat using wastewater in agriculture about the unexposed group, it is the inhabitants of a village which is south of Settat.It is well established that the prevalence and incidence of parasitic diseases varies from one region to another depending on the socioeconomic and hygiene status of the population[15]. The epidemiological study carried out by Bouhoum K.[6] (cited above) showed the decrease in the prevalence of intestinal helminth infections in the population and linked this to the improvement of their living environment.Our study shows parasitical risk that human and animal population are exposed when raw wastewater is reused for irrigation in the region of Settat particularly and complements other studies that have highlighted the potential risks reuse of wastewater in agriculture ([56],[34],[57]).Results relating to raw wastewater showed that the risk of infection is relatively important for both the animal consumes the plant as for the farmer because of manual work requiring contact with the water and soil, especially when measures hygiene are not followed, not forgetting consumers (ingestion of contaminated culture product or zoonoses). This risk drops significantly if irrigation is done by treated water, the use of treated wastewater for irrigation would constitute an alternative to fill the water deficit in the region and reduce the risk of helminth infections in humans and the animal. Given the purification efficiency obtained, the documentation suggests that it would be possible to reuse the treated wastewater in agriculture. However, it would be important to assess the risk of parasite infection incurred by the exposed population and especially the consumer, as the eggs of parasitic helminths (Ascaris and hymenolepis) and strongyles were found in 31% of samples although that it is with very low concentrations, and recent epidemiological research work shows that a limit of <0.1helminth egg/l is needed if children under 15 years are exposed[58].Also, because irrigated fields presents wet soils allowing prolonged survival and maturation of helminth eggs like those of Ascaris[6]. Indeed, eggs of Ascaris sp are very strong, their persistence in soil up to 7 years when conditions of moisture and temperature are favorable[26]. Moreover, according to Strauss & al., the most persistent of all helminthic pathogens are Ascaris eggs and thus can be used as a parasite indicator when dealing with hygienisation of excreta ([59],[60]). The living standards of people in this area is generally low with a level of education and hygiene unsuitable thereby increasing the risk of parasitic infection.It is in this sense that we made an additional study to assess the health risk inherent in the reuse of wastewater (raw and treated) in the region of Settat, a parasitological control was performed on samples of cultures (irrigated by these waters) and ground. The risk will be evaluated on the basis of these results and epidemiological data, that portion shall be treated in a following document.

5. Conclusions

- Indeed, the release of such water in nature is likely to jeopardize the health of the person who came into contact (direct or indirect) with helminth parasites transmitted by these waters and contaminate the receiving environment. It is essential firstly to encourage farmers continuing to use this raw sewage for irrigation to replace them with treated water, and secondly, to predict the development of additional basins that would treat waters of the city even when abundant precipitation affecting the flow of water entering the WWTP. This will avoid the diversion of these waters into nature because though this is a solution for maintaining the purifying system of the WWTP, it is a cause of the spread of pathogens in the environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors gratefully acknowledge all collaborators in this study especially: i) Mr Hassoune Zakaria and all employees who work at the wastewater treatment plant for their collaboration, ii) We would like to thank RADEEC for their collaboration, iii) Dr. Cabaret J. and his research team (INRA Nouzilly; France) for their hospitality , time allowed and generosity, iii) Pasteur Institute of Morocco particulary Dr M. ALLALI for his help to realize sampling logistics.

References

| [1] | Jemali A. & Kefati A., « Réutilisation des eaux usées au Maroc », In: Forum sur la gestion de la demande en eau Ministère de l_agriculture, du développement rural et des eaux et forêts. Maroc, Administration du Génie Rural, Direction du Développement et de la Gestion d’Irrigation, 2002. |

| [2] | Online Available:http://www.ambafrance-ma.org/maroc/agriculture.cfm |

| [3] | Oubrim N., Ennaji M. M., Hajjami K., Bennani M., Hassar M. & N. Cohen, « Microbiological Impact of Treatment Lagoons on The economics of Water for Reuse in Agriculture a Case Study in Morocco (Settat and Soualem Regions) », Cell. Mol. Biol. 57, 2011. |

| [4] | Cabaret J. & Moussavou Boussougou M.N., « Boues d’épuration : gestion des risques sanitaires », L’action vétérinaire, 1588, p.22-25, 2002. |

| [5] | Sawadogo GJ., Teko-Agbo A. et Y. Akpo, « Réutilisation des eaux usées en agriculture à Dakkar (Sénégal) : Impact sur la santé et l’environnement », Collection Environnement/Aspect sanitaire des eaux usée/ Traitement et réutilisation des eaux usées : impact sur la santé et l’environnement, IAV Edition, p.95-102, 2009. |

| [6] | Bouhoum K., « Impact sanitaire de la réutilisation des eaux usées en agriculture à marrakech sur les parasitoses intestinales des enfants », Collection Environnement/Aspect sanitaire des eaux usée/ Traitement et réutilisation des eaux usées : impact sur la santé et l’environnement, IAV Edition, pp.55-72, 2009. |

| [7] | Toze S., « Microbial pathogens in wastewater », CSIRO Land and Water Technical report 1/97, 1997. |

| [8] | Bouhoum K., Habbari K., Jana M. & Schwartzbrod J., « Étude épidémiologique des helminthiases intestinales chez l’enfant de la zone d’épandage des eaux usées de la ville de Marrakech », Actes du colloque international sur la conception, naissance et petite enfance au Maghreb, Marrakech, 1994. |

| [9] | Habbari Kh., «Impact de l'utilisation des eaux usées sur l'épidémiologie des helminthiases et de la croissance chez l'enfant d'El Azouzia», Thèse de 3ème cycle, Fac. Sci., Marrakech, 1992. |

| [10] | Raisannen S., Ruuskanen L. & Nyman S., «Epidemic Ascariasis evidence of transmission by imported vegetables», Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 3, p.189-191, 1985. |

| [11] | Shuval H.I., Yekutiel P. & Fattal B., «Epidemiological evidence for helminth and cholera transmission by vegetables irrigated with wastewater : Jerusalem a case study», Wat. Sc. Tech., 17, pp.443-442, 1984. |

| [12] | Shuval M, Adin A., Fatal B., Rawitz E, Yekutiel P., «Wasteater irrigation in developping countries : Health effects and technical solutions», World Bank technical, no51,pp.21-38,1986. |

| [13] | Srivastava V.K. & Pandey G.K., «Parasitic infestation in sewage farm workers», Ind. J. Parasitol. 10, (2).,pp.193-194, 1986. |

| [14] | WHO, « L’utilisation des eaux usées en agriculture et en aquaculture: recommandations à visées sanitaires », Rapport d’un groupe scientifique de l’OMS, Organisation mondiale de la santé, Rapport technique n 778, Genève, 1989. |

| [15] | Khallayoun K., Ziad H., Lhadi E.K et Cabaret J., « Réutilisation des eaux usées brutes en agriculture au Maroc : Risque potentiel de contamination des cultures et du sol par les œufs d’helminthes », Collection Environnement/Aspect sanitaire des eaux usée/ Traitement et réutilisation des eaux usées : impact sur la santé et l’environnement, IAV Edition, p103-111, 2009. |

| [16] | Dssouli K.., « Traitement et réutilisation des eaux usées en agriculture au Maroc Oriental (Oujda): Etude des helminthes parasites », Thèse de Doctorat d'Etat en parasitologie, Fac. Sci. Oujda, 133p, 2001. |

| [17] | Online Available :http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/french/nm/nasm/info/brochure.htm MAAARO, 2009 |

| [18] | RADEEC, Régie Autonome de Distribution d’Eau et d’Electricité de la Chaouia, Fiche technique relative au projet de la station d’épuration de la ville de Settat. Ministère de l’intérieur, Wilaya de la région Chaouia Ouardigha. Royaume du Maroc, Settat, 2003. |

| [19] | Online Available:http://www.tageo.com/index-e-mo-v-26-d-m71695.htm |

| [20] | Zerouali, A., Lakfifi, L., Larabi, A., Ameziane, A., « Modélisation de la nappe de Chaouia Côtière (Maroc) », First International Conference on Saltwater Intrusion and Costal Aquifers-Monitoring, Modeling and Management, Essaouira, Morocco, April 23-25, 2001. |

| [21] | El Kettani S. & Azzouzi M., « Prévalence des helminthes au sein d’une population rurale utilisant les eaux usées à des fins agricoles à Settat (Maroc) », Environnement, Risques & Santé, Vol. 5, no.2, mars-avril, 2006. |

| [22] | RADEEC, Régie Autonome de Distribution d’Eau et d’Electricité de la Chaouia, Rapport de gestion de l’exercice: Assainissement liquide, 2009. |

| [23] | Schwartzbrod J. and Strauss S., « Devenir des kystes de Giardia au cours d’un cycle d’épuration », TSM no.06, pp.331-334, 1989. |

| [24] | Arther R.G., Fitzgerald P.R. & Fox J.C., «Parasite ova in anaerobically digested sludge». J. Wat. Pollut. Cont. Fed.; 53 pp: 1333-1338, 1981. |

| [25] | Alouini Z., Achour H. & Alouini A., « Devenir de la charge parasitaire des eaux usées traitées dans le réseau d'irrigation "Cebala", Agriculture Durabilité et Environnement. Zaragoza: CIHEAM, 117-124, 1995. |

| [26] | Mara D. D. et Silva S. A., « Removal of intestinalis nematode eggs in tropical waste stabilisation ponds », J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 89, pp.71-74, 1986. |

| [27] | Jiménez B., Mara D., Carr R. & Brissaud F., «Wastewater Treatment for Pathogen Removal and Nutrient Conservation: Suitable Systems for Use in Developing Countries», Wastewater irrigation and health, 149-169, 2010. |

| [28] | Stien J. L. et Schwartzbrod J., « Devenir des oeufs d'helminthes au cours d'un cycle d'épuration des eaux usées urbaines », Revue internationale des séries de l'eau, 3 (3/4), p.77-82, 1987. |

| [29] | Alouini Z.. « Flux de la charge parasitaire dans cinq stations d’épuration en Tunisie », Revue des Sciences de l’Eau, 453-462, 1993 |

| [30] | Ben Ayed L, Schijven J, Alouini Z, Jemli M. & Sabbahi S , « Presence of parasitic protozoa and helminth in sewage and efficiency of sewage treatment in Tunisia », Parasitol Res 105,pp.393–406, 2009. |

| [31] | Stott R, Jenkins T, Shabana M, May E., « A survey of the microbial quality of wastewaters in Ismailia, Egypt and the implications for wastewater reuse», Water Sci Technol., 35 (11–12), p.211–217, 1997. |

| [32] | Guessab M., Bize J., Schwartzbrod J., Mani A., Morlot M., Nivault N. & Schwartzbrod L., « Wastewater traetement dry infiltration percolation on sand: results in Ben Sergao», Morocco, Wast. Sci. Tech., 17, pp.91-95, 1993. |

| [33] | Dssouli K., El halouani H. & Berrichi A., « L’impact sanitaire de la réutilisation des eaux usées brutes de la ville d’Oujda en agriculture: Etude de la charge parasitaire en oeufs d’helminthes au niveau de quelques cultures maraîchères », Biologie & Santé, vol.6, no.1, 2006. |

| [34] | El Addouli J. and Chahlaoui A., « Suivi et analyse du risque lié à l’utilisation des eaux usées en agriculture dans la région de Meknes au Maroc », Institut national de l’ingenierie de l’eau et de l’environnement, Sud Sciences et technologies no.16, p.29-35,2008. |

| [35] | Kouraa A, Fethi F, Fahde A, Lahlou A, Ouazzani N ;, « Reuse of urban wastewater treated by a combined stabilization pond system in Benslimane (Morocco) », Urban Water no.4, pp.373–378, 2002. |

| [36] | Bouhoum K., « Etude épidémiologique des helminthiases intestinales chez les enfants de la zone d'épandage des eaux usées de Marrakech / Devenir des kystes de protozoaires et des oeufs d'helminthes dans les différents systèmes extensifs de traitement des eaux usées », Thèse de Doctorat d'Etat, Fac. Sci. de Marrakech, 227p. 1996. |

| [37] | Bouhoum K., Amhamid O., Habrari KH. & Schwartzbro J., « Devenir des œufs d’helminthes et des kystes des protozoaires dans un canal à ciel ouvert alimenté par les eaux usées de Marrakech », Rev. Sci. Eau 2, pp.217-232, 1997. |

| [38] | Mrabet K., « Etude de la contamination des champs d'épandages de la ville d'Oujda par les œufs d'helminthes et leur transmission dans le réseau trophiques », Th. 3ème cycle, Fac. Sci. Oujda, 120p, 1991. |

| [39] | Schwartzbrod J. et Banas S., «Parasite contamination of liquid sludge from urban wastewater traetment plants», Wat. Sci. Tech., Vol. 47, no.3, pp.163-166, 2003. |

| [40] | Graham HJ., «Parasites and the land application of sewage sludge», Research report/research program for the abatement of municipal pollution under provisions of the Canada-Ontario agreement on great lakes water quality, Training and Technology Transfer Division, Environmental Protection Service, Environment Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, 1981. |

| [41] | Grimason AM., Smith HV., Young G. and Thitai WN., «Occurrence and removal of Ascaris sp. ova by waste stabilisation ponds in Kenya», Water Sci Technol., 33(7), pp.75–82, 1996. |

| [42] | Klutse A.et Baleux B., « Elimination des œufs de nematodes et des kystes de protozoaires des eaux usées domestiques par lagunage à microphytes zone Soudano-Sahélienne », Revue des sciences de l’eau, p563-577, 1995. |

| [43] | WHO, World Health Organisation Guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and greywater, Vol.1, Policy and regulatory aspects, 2006. |

| [44] | Chalabi M.M., « Performance d'élimination des œufs d'helminthes et étude de leur viabilité dans le Chenal Algal à Haut Rendement », Thèse de 3ème cycle, Fac. Sci. Marrakech, 120p, 1993. |

| [45] | Amahmid O., Asmama S. & Bouhoum K., « Urnab wastewater treatment in stabilization ponds: occurrence and removal of pathogens», Urban Water 4, pp.255- 262, 2002. |

| [46] | Bouhoum K., Amahmid O. and Asmama S., « Wastewater reuse for agricultural purposes: Effects on population and irrigated crops», Proceeding of international symposium environnmental pollution control and waste management, EPCOWM, Tunis, Part II, pp.582-586, 2002. |

| [47] | Naour N., « Impact de la réutilisation des eaux usées en agriculture sur la contamination des cultures par les œufs d’helminthes », Thèse de 3ème cycle, Université Cadi Ayyad, Fac. Sci. de Marrakech, 101p, 1996. |

| [48] | El Guamri Y. & Belghyti D., « Charge parasitaire des eaux usées brutes de la ville de Kénitra (Maroc) », Afrique SCIENCE, 03(1), p.123-14, 2007. |

| [49] | Ait Abdelalai R., « Les parasitoses intestinales dans la province de Marrakech de 1978 à 1982 », Thèse Médecine. Fac. Mèd. Phar. Casablanca, 1983. |

| [50] | Khnifi A., « Parasitoses intestinales au centre hospitalier d'Oujda de 1978 à 1986 », Thèse de Médecine, Fac. Mèd. Phar., Casablanca, 175p, 1987. |

| [51] | Online Available:http://www.tutiempo.net/clima/Nouasseur/601560.htm |

| [52] | Thevenot P., «Parasitologie des boues des Stationsd’épurati-on », Aspects bibliographiques, Thèse de l’université de Nancy I, Faculté des Sciences Pharmaceutiques, 1988. |

| [53] | Hoek V. D. W.; Hassan M. U, Ensink J.H.J, Feenstra S., Raschid-Sally L., Munir S., Aslam R., Ali N., Hussain R. and Y. Matsuno, «Urban wastewater in Pakistan: A valuable resource for agriculture», Research Report 63. Colombo, Sri Lanka: IWMI. Forthcoming, 2002. |

| [54] | Ensink J.H.J., Aslam M.R, Konradsen F., Jensen P.K. & Hoek W.V.D., «Irrigation and drinking water in Pakistan »,Working Paper 46, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, 2002 |

| [55] | El Kettani S., Azzouzi E., Boukachabine K., El Yamani M., Maata A.and Rajaoui M. , « Intestinal parasitosis and use of untreated wastewater for agriculture in Settat, Morocco », Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, Vol. 14, No. 6, ,2008. |

| [56] | Cisse G., Kientga M., Boureima O. & Tanner M., « Développement du maraîchage autour des eaux de barrage à Ouagadougou : Quels sont les risques sanitaires à prendre en compte ? », Cahiers Agriculture ; 11 p.31-8, 2002. |

| [57] | Gagneux S., Schneider C.,Odermatt P., Cisse G., Cheikh D., Ould Selmanem L., Ould Cheikh D. , Toure A. & Tanner M., « La diarrhée chez les agriculteurs urbains de Nouakchott en Mauritanie » , Médicine Tropical, 53, p.253-258, 1999. |

| [58] | Blumenthal U.J., Mara D.D., Peasey A., Ruiz-Palcios G., & Stott R., «Guidelines for the microbiological quality of treated wastewater used in agriculture: Recommendations for revising WHO guidelines», Bulletin of the World Health Organization,no.78, pp.1104-1116, 2000. |

| [59] | Strauss M., « Human waste (excreta and wastewater) reuse», Contribution to: ETC./SIDA bibliography on urban agriculture, EAWAG/SANDEC, Duebendorf, 2000. |

| [60] | Adam M.P., « Possible scenarios of environmental transport, occurrence and fate of helminth eggs in light weight aggregate wastewater treatment systems», Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol., no. 9, pp.51-58, 2010. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML