-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Resources and Environment

p-ISSN: 2163-2618 e-ISSN: 2163-2634

2012; 2(1): 55-66

doi: 10.5923/j.re.20120201.08

Managing Scarcity in the Dryland of the Eastern Sudan: the Role of Pastoralists' Local Knowledge in Rangeland Management

Yasin Abdalla Eltayeb El Hadary , Narimah Samat

Geography Section-School of Humanities Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) 11800 Penang, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Yasin Abdalla Eltayeb El Hadary , Geography Section-School of Humanities Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) 11800 Penang, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The misconception that seems to be dominant among many academicians and policy makers is that pastoralists are often to be blamed for degrading the resources they rely upon and are indifferent about the ecological consequences of their actions. Melville Herskovits’ theory of the ‘East African cattle complex’ and Hardin’ theory of the ‘tragedy of commons’ has viewed indigenous pastoralists who shared grazing resources communally are ignorant and environmentally destructive. Recent researches on range ecology and social science have found evidence that knowledge is not being the scarce commodity among pastoralists. The Scoones’ new thinking approach has shown that pastoralists are often knowledgeable about their surrounding environments and capable of regulating the use of grazing resources among local groups as well as with outsiders in a sustainable manner. Despite this fact, little has been said about pastoralists' local knowledge and even less is known about the role of this knowledge in securing livelihood of the overwhelming majority of the inhabitants in the dry lands. This paper focuses on the role played by Sudanese pastoralists’ local knowledge in rangeland management and the current constraints that have taken place. The main objective is to investigate how this knowledge is powerfully reflected in pastoral adaption strategies to the ecological marginality of Gedarif state in the eastern Sudan. Filling the existing lack of literature in indigenous knowledge and to highlight its importance in securing livelihood, minimizing risks and conserving the environment are the main contributions of this article.

Keywords: Drylands, Herd Mobility, Local Knowledge, Natural Resources, Pastoralists, Rangelands Management, Sudan.

Cite this paper: Yasin Abdalla Eltayeb El Hadary , Narimah Samat , "Managing Scarcity in the Dryland of the Eastern Sudan: the Role of Pastoralists' Local Knowledge in Rangeland Management", Resources and Environment, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 55-66. doi: 10.5923/j.re.20120201.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

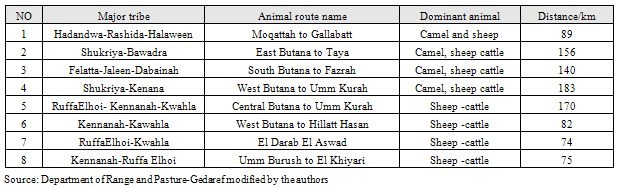

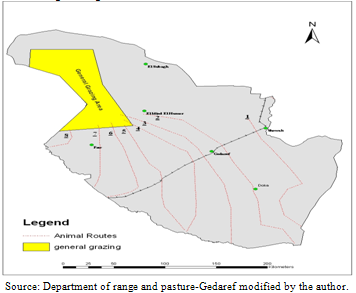

- Drylands cover an area of about 5.2 billion hectares and roughly one fifth of the world population lives in these areas (UNEP, 1992). This implies that close to one billion people worldwide depend directly upon the drylands for their livelihoods (Mwangi & Dohrn 2006). In Africa alone, it constitutes 43% of the total area, 40% of the continent’s population and 59% of all ruminant livestock (Scoones 1994). It secures livelihood for more than 50 million pastoralists and up to 200 million agro-pastoralists (De Jode 2010). And it has been reported that most of the poorest countries as well as world’s poorest women in the world are found in Africa’ drylands (Mortimore, 1998). Ecologically this region is characterized by having: immature eco-system, aridity, variability, water scarcity and very short growing season that hardly reaches 200 days (FAO, 1978; El Hadary 2010). The annual rainfall varies over space and time, ranging between 75 to 600 mm annually (LeHouerou 1989). Thus accessing water and pasture is considered as one of the major constraints in improving production in dryland regions.Receiving less than 1000 mm of rainfall annually in less than 180 days (Mortimore, 1998), world’s drylands are in a need of special type of land use management. It is important to note that not all drylands areas are limited by water. There are pockets of wetlands, which offer valuable dry season grazing, flood recession farming, or irrigation opportunities (Mwangi & Dohrn 2006). Therefore, Pastoralism rather than pure farming is considered as a dominant activity in Africa’s fragile drylands (Grigg, 1974). According to Scoones (1994) pastoralism which is based on mobile livestock keeping is economically the most efficient, securing livelihood for large sections of the population and causing less ecological impact on the environment. Even the return per area of fuzzy nature (mobile) is higher than well defined property rights (sedentary) or commercial ranching (Scoones, 1993; Mwangi & Dohrn 2006). Recent evidences coupled with the failure of several project established to settle pastoralists (Sandford, 1983) challenge these assumptions and indicate that pastoralists are often knowledgeable and capable to manage their grazing resource in appropriate manner. In fact, there are numerous examples, which show that pastoralists’ behavior in managing rangeland is ecologically, and economically highly productive (Behnke et al., 1993; Niamir-Fuller, 1999; Sand- ford, 1983; Scoones, 1993; Scoones, 1994) and that knowledge not being the scarce commodity among them. Many of the so-called traditional herding practices, which were once regarded as primitive and misguided are now recognized as sophisticated and appropriate (Chamber, 1983). The theory of “New Thinking on Range Management” mentioned by (Scoones 1994) in the book living with uncertainty has challenged many previously held notions such as cattle complex, tragedy of the commons, overgrazing, overstocking and beyond the carrying capacity. Scoones draws an important distinction between equilibrium and non- equilibrium environments. The former are characterized by gradual vegetation change and predictable rainfall patterns, where livestock populations are limited by the available forage, and hence, excessive numbers of livestock above a “carrying capacity” have a negative effect on vegetation. Non- equilibrium environments, in contrast, are highly dynamic, where rainfall dominates the production potential of both grass and livestock, and hence, livestock populations are limited by drought. Scoones acknowledged the process of tracking, matching the available feed supply with animal numbers at a particular site, and emphasizes the importance of mobility for maintaining opportunistic tracking strategies. Therefore, the past notion which says pastoralists are ignorant and environmentally destructive needs to be revised. (Chambers, 1983) states that without a continuous dialogue and mutual understanding between indigenous knowledge and modern sciences any effort to confront natural resource management would at best be wasted.From these arguments it becomes clear that pastoralists’ Indigenous knowledge or local knowledge, whatever the terminology being used, had played vital role in rangeland management. This knowledge is strongly reflected in herding practices, adaption strategies and become part of their cultural practices in everyday life. This knowledge, which is an output of repeated experiences, accumulated through time. It is dynamic and it can be updated, modified, and amended as a result of acquiring new experiences and observations (Fernandez-Gimenez, 2000). Therefore, it depends heavily on the ability of pastoralists to pursue mobility and moving their herds across fairly large areas (Niamir- Fuller, 1999). Through mobility pastoralists can access information on socio-spatial heterogeneity, animals’ behaviour and performance, carrying capacity, spread of disease, quality and quantity of different plants species, and water availability. Indictors such as the use of local calendar, plant species, and appearance of some insects are some useful measurements used to evaluate rangeland condition. To ensure the quality of their assessment, specialized agents such as the tribal leaders, experienced herders, and scouts have taken the responsibility to collect and distribute information among the entire community. This traditional information system has been facilitated by the existence of flexible common property resource management institutions. Tribal leader system or native administration is considered as an essential body to regulate access and use of collective information. Across many African countries including Sudan, planners and decision makers don't recognize and appreciate the significance of local knowledge-based rangeland management, consequently, much interfered by policy makers in their common desire to modernize livestock production and settle pastoralists. Privatization or open access of communal land since 1970s has strongly disturbed herd mobility and thus threatening the use of pastoralists’ indigenous knowledge. This paper aims to examine the role played by local knowledge-based practice in rangeland management in the drylands of Sudan. The overall objective is to explain how this knowledge is reflected in pastoral production and in rangeland management strategy. To look into pastoralists’ indigenous knowledge in depth and to avoid the risk of over generalization, the focus of this article is narrowed down to Gedarif state of the eastern Sudan. This article aims to answer the following questions: What is the positive role played by pastoralists’ local knowledge in range management? What are the strategies adopted by herders to cope with scarcity of grazing resources in drylands? What changes in local knowledge-based range management strategies can be observed in Sudan? To answer these questions, the article is based on interviews, group discussions and questionnaire with 300 household covering 19 villages distributed in eastern Sudan, primarily in the northern part of Gedarif state (see figure 1). The uses of the secondary resources help putting the article in regional and international context. Designing and drawing of maps have been facilitated by the use of Geographical information System tool (GIS).

2. The Concept of Indigenous Knowledge

- In order to address the issue of local knowledge, it is therefore necessary to formulate a working definition of the term “indigenous knowledge”. This term has entered the arena of debate since 1987 when the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) found it useful for sustainable development. The current growing interest is partly due to the recognition that such knowledge can contribute to the conservation of biodiversity, rare species, protected areas, ecological processes, and to achieve sustainable development in general (Berkes et al., 2000). “Indigenous knowledge” local knowledge, “local knowledge”, traditional knowledge”, “folk knowledge”, “indigenous technical knowledge”, “traditional ecological knowledge” and “indigenous ecological knowledge” are various terms used to define knowledge held by the local communities in specific location. Whichever term is being used it refers to the unwritten collective experiences acquired by a particular community for hundreds or thousands of years used for securing their livelihood (Ahmed, 1994). It is dynamic, flexible, adaptable, and unique to a given culture or society (Warren, 1993), evolves by adaptive processes and handed down through generation by cultural transmission (Berkes et al., 1995). The authors prefer the term “local knowledge” as it gives the dimension of a place where the collective experiences are generated, used and transferred by observers who were in direct contact with the environment. In the context of this paper it means the repetitive experience and skills by which pastoralists can derive the highest benefits from the available natural resources (Behnke & Kerven, 1995). Traditional forecasting methods, soils colour, types of plants, and appearance of some insects are some indicators used to acquire a concrete knowledge about rangeland condition. Lack of documentation, qualitative rather than quantitative, local view, verification by repetition, transferring orally, and inequality in accessing are some limitations of local knowledge. Despite these weaknesses it constitutes a foundation on which scientific improvement in can be built (Chamer, 1983).There is a never ending debate between local knowledge and scientific knowledge. According to Warren (1991), the term “indigenous knowledge” describes the knowledge developed by a given community, which is different from scientific knowledge systems, international knowledge systems or “Western” knowledge systems generated through universities or at government research centers and private industry. This sharp distinction has sent the wrong signal that local knowledge is primitive and traditional “traditional” in a sense that Warren et al (1995) put it; it denotes the 19th-century attitudes of simple, savage, and static. Not denying the differences such as that western science is based on research. The similarity can be found in that both are generated through observations, developed through repeated experiences and done by experts or skills people. Agrarwal (1995) has cautioned against overemphasizing the differences between western science and traditional knowledge and questioned if the dichotomy is real. Some scholars went even further to reveal the advantages of pastoralists’ local knowledge over western model specifically in natural resource management. According to Scoones (1994) the value of communal area cattle production far exceeds returns from ranching. If actual stocking rate are used, communal area returns are 10 times higher per hectare. Turner and Hiernaux (2002) demonstrate that maps of livestock activity based on local herders’ knowledge are more effective and accurate for management than those rigorously developed through spatial modelling. Furthermore, systematic comparisons proved that pastoralists’ indigenous breeds can provide higher productivity than improved cross-breeds (Blench, 1999). The advantage of this comparison, although their findings are questionable, is to lay the ground for embarking on further research.

| Figure 1. Location of Gedarif state |

| Figure 2. Analytical framework of the study |

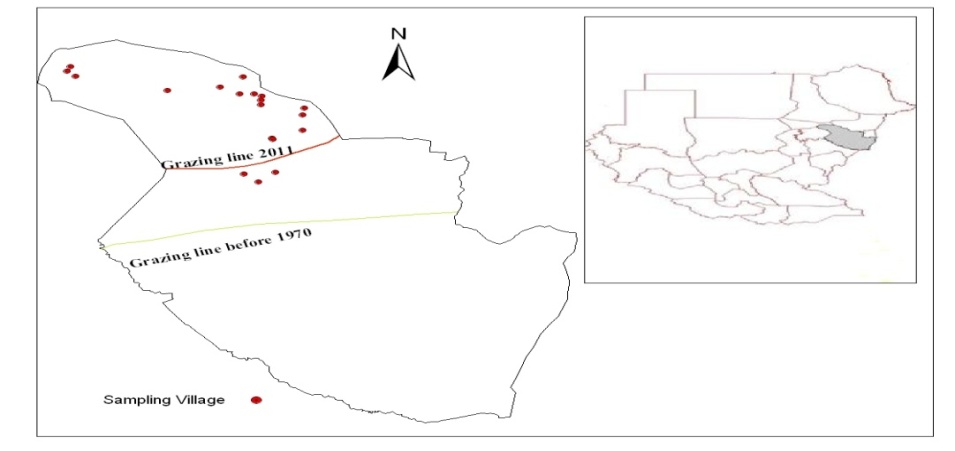

3. Analytical Framework

- To investigate how pastoralists’ local knowledge is reflected in range management and the recent constraints that have taken place, an analytical framework has been developed (Figure 2). Based on theories of anti movement (Hardin & Herskovits’) and lack of proper knowledge about the importance of pastoral economy has led planners and decision makers to formulate policies that harm pastoralists. Most of their interventions in rangeland development have often failed to strengthen pastoralists’ ability to cope and secure their livelihood in high risky environment. Expansion of farming activities at the expense of grazing land and attempts to settle pastoralists have made pastoralists more vulnerable and undermined their adaptation strategies. In Sudan, the introduction of land tenure act of 1970 has led to profound negative impact on pastoral economy. Changes in communal rights coupled with the repeated drought under the influence of market economy, have threatened the existence of herders’ mobility; one of the basic pillars of local knowledge-based range management strategies. Their useful knowledge becomes inefficient and can no longer make full use of it in range management. These have resulted in massive degradation in rangeland conditions, spread of deep poverty, creating huge social problems and accelerating the rate of conflict among land users.

4. The Role of Pastoralists’ Local Knowledge in Adaptation Strategy

4.1. Herd Mobility

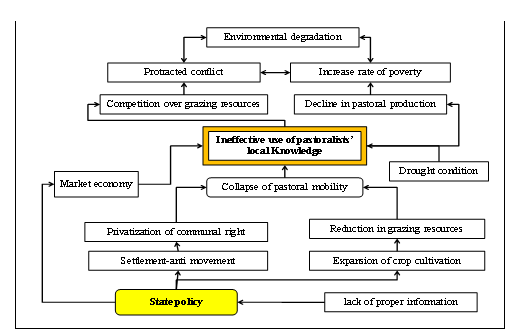

- Pastoralists' knowledge of the fragile and in immature eco-system is reflected clearly in their adaptation strategies to the drylands milieu. Pastoralists adopted several techniques to secure their livelihood in an unpredictable environment. The most efficient strategies include herd mobility, flexible stocking densities, and diversification in animal species, as well as in income generation activities. This section focuses in these strategies not as an end in itself, but to evaluate pastoralists’ local knowledge based range management. For hundreds or thousands of years pastoral communities across Africa such as Massi, Gabbra, and Arrial in Kenya; Borana Oromo and Afar in Ethopia; Berber in North Africa; Fulani or Fulbe in west Africa; Beja, Shukriya and Rashida in the eastern Sudan have adopted mobility as highly efficient strategy to cope with scarcity of resources in drylands of African Sahel. Availability of pasture and water are the essential factors behind the determinant of time and direction of their movement. Generally speaking, they move to the north during rainy season and to the south during dry season. Irregular movements out of these cycles occur in case of conflict and disease outbreaks (Niamir- Fuller, 1999).Specifically in Gedarif state there are two types of mobility: the movement of local tribes that inhabited northern part (Butana) and the movement of non resident tribes (outsider) that spent the rainy season in Butana. This strategy allows both groups to access palatable grasses, minimize the spread of animal diseases and recover after shocks. The discussions with old people have shown that local pastoralists in Butana are in move almost all year round. During the rainy seasons they move with their families to the western part where water and pasture are available, particularly they graze in communal grazing land known as General Grazing Area (GGA) (see figure 3). The idea behind this movement is to share the resources with (outsiders) in the western part and reserve the rest of Butana for the dry seasons. GGA is opened freely for both local and outsiders to graze during rainy seasons. In the summer time local pastoralists graze around their Dars and move to the River Atbara and Blue Nile when there is acute shortage of water. Regarding the second group (outsider) they have also two types of movement: during rainy seasons to the northern part (GGA) and during the summer to the area of origins mostly southern Gedarif. From late June up to the early July most of pastoralists if not all in Gedaref State move to the Butana area to escape from insects (biting flies) and muddy condition in the southern part and above all access natural and highly nutritious grass Belpharis edulis (Siha) in Butana. They will stay up to the end of October when the existing sources are dried up. This implies that lack of water in (GGA) is an essential strategy adopted by the local to ensure an early leaving of outsiders. The availability of water and crop residues in the southern part appears to be as pushing factor behind the movement from Butana. Immediately after harvesting, the farmers leave the residue for pastoralist to graze it freely. This type of mutual and symbiotic relation between farmers and herders is known locally as (TALK). By so doing farmers also benefited from natural fertilizer of livestock (manure).Mobility is considered as a strategy rather than just a kind of movement, therefore, huge task need to be settled before pastoralists decide to move. When a movement is planned expert herder or in surveillance accepted and trusted by both (people in the area of origin and destination) is sent out to evaluate the condition of rangeland and ensure that it is safe to move. The expert or scout had to be an experienced person, strongest, and intelligent ones who knew to evaluate the conditions of an area (finna), and interpreting range conditions (De Jode, 2010). This entails that the observant has ability to measure what is known in the ecological studies as the “carrying capacity” of the rangeland. When they return, an indispensable meeting is held to discuss the followings: evaluate the information, take decision to move, and make division of tasks based on age and gender. When the decision to move is made, pastoralists have to follow their traditional animal routes. Historically in Gedarif state there are eight corridors Maraheel distributed throughout the area to organize the seasonal movement though agricultural areas (figure 3 and table 1).It is worth mentioning that moving in and out of Butana is not a direct journey; instead pastoralists have to settle for few days (7-15) in their ways to the final destination and do the same in their way back to their origin area. This system is known locally as Nazla, meaning rest for a while. The selection of places for Nazla depends on the understanding of its geographical setup and some predetermined arrangements. Pastoralists always select the area near and close to water points and pasture (khors, wadis, permanent water centres and forests). Pastoralists justifications of Nazla include change to better grazing, buying their daily needs (sugar, coffee, cloths) from closer markets, rest for animals, get some medicines for both and get rid of the weakest animals. Besides, practice of their social events such as marriage, wedding, and so forth. The advantages of mobility as were cited by pastoralists include that it is a risk management strategy, necessary for optimal utilization of the meagre recourses that varied over space and time and help in conserving the environment. For them, ''Allah created animals with four legs so as to move not settle and stay for a long time in one place." They mentioned that mobile livestock is even more productive than their sedentary counterparts or commercial ranching. This article argues that herd mobility is a crucial strategy to secure livelihood of the pastoral people in drylands, and need to be seen as a trump card to be strengthening not a problem to be eliminated (CAPPRI, 2010). Recently, mobility is starting to take root in many parts of African dryland. Many regional institutions are recognizing the huge benefits to be reaped from supporting livestock mobility (De Jode, 2010). For instance World Bank has provided support for pastoral association in the Sahel (Scoones 1994).

| Figure 3. Animal routes in Gedarif state |

|

4.2. Flexible Stocking Densities

- Based on their local knowledge, pastoralists have come to know that variable stocking densities is a valuable strategy to cope with the fluctuation of rangeland condition in drylands. This “opportunistic approach” as indicated by Sandford (1983) is necessary to establish flexible short term reactions, viable long-term trends, and recover after any crises. There- fore, pastoralists in Sudan and across the African Sahel pursue a variety of strategies to adjust their number of animals to match the availability of natural grazing resources. Reducing animal size either through marketing or social network is necessary to minimize risk or shocks during a crisis. Marketing livestock in time and reinvesting in herd recovery after a drought is helpful to buffer the risk (Holtzmann & Kulibaba, 1995). The group discussions have shown that during drought, pastoralists used to distribute their livestock among their relatives who live in different places. The philosophy behind this strategy is to ensure that at least some parts of the herd survive (Toulmin, 1995) in order to rebuild the stock when the crises are over. During good seasons pastoralists use their own breeding knowledge to maximize their herd so that enough heads of livestock can survive after droughts or shocks. The survey has shown that the number of females in each herd is (73%) compared with male which is (27%). Therefore, herd owners are interested in having larger number of females in all kinds of animal species since the female represents the reproductive type. Several points need to be highlighted to understand the hidden ideas behind the strategy of increasing animal number. First, the process of recovery after drought does not happen overnight and it takes a long time. Thus, maximizing animal number will increase the speed of recovery; second, it helps in buying fodder and water during crises when the price of animal declines very sharply, therefore pastoralist needs to sell more animals to buy few forage; third, for fear of unexpected disaster, this idea has a lion’s share in the discussion (unpredictable environment) and finally for social position (prestige) and this idea has little share in the discussion.

4.3. Diversification of Livestock

- This type of adaptation reflects clearly the pastoralists’ ecological knowledge and the deep understanding of immature eco-system. A herder's knowledge about a particular plant, includes the ability to recognize the conditions in which it grows, specific locations where it can be found locally, its palatability for different species of livestock, its root system, its resistance to grazing, and its value for other human uses such as fuel, medicine, or food (Fernandez-Gimenez, 2000). Having this knowledge about the characteristics of grass and its variations over space and time, coupled with understanding of the attitudes (behaviour) of animals in grazing, led pastoralists to breed different species of livestock. In response to the question about the type of animal in the past around (83%) mentioned that they used to graze all four types of animals (camel, cattle, sheep, and goats) and the rest (17%) mentioned more than two types. By so doing pastoralists achieve different advantages in feeding requirements, adjustments to grazing pressure, drought survival (Sandford, 1983) and ensure optimal exploitation of the available vegetation. This strategy helps them to know that camel and goats which are considered as drought resistant prefer browsing while cattle and sheep (sensitive to climate) favour to graze grasses. The advantages of this strategy include maximizing the use of available and meager grazing resources (browsing, and grassing); it enables pastoralists to minimize losses when livestock disease epidemics occur (risk spreading strategy) (Watson, 1994), and creating job opportunities for all members regardless of their age and sex to participate in range management. In the study area, the young always move with smaller animals (sheep and goats) while adults move with high number and large animals (camel and cattles); even women help in taking care of the small and milking animals. Our data has shown that the average number of livestock per household is 110 (sheep), 29 (goats), 27 (camel) and 18 (cattle). Compared with the situation before 1970s, it seems that there is sharp decrease in animal size with profound change in herd structure. Looking behind the figure, one can argue pastoralists have taken new measurement towards small ruminants. Under the sharp decline in grazing resources concentration of sheep rather than other types it seems a sound strategy. This new strategy seems logical due to the fact that sheep are highly productive (doubling itself soon), easily to market, and less water demanding compared with cattle.

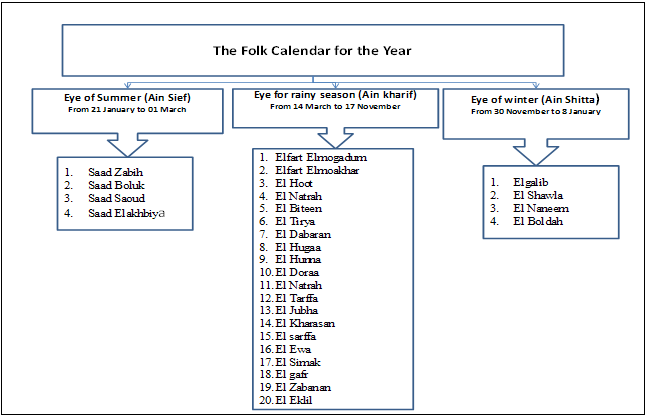

5. Grazing Management Strategy

- Managing water seems to be a nightmare for pastoralists, particularly in Gedarif state where the geological structure is dominated by basement complex. This type of rock is considered as not water bearing (Abusin, 1995). Therefore pastoralists depend mainly on artificially excavated holes known locally as Hafirs rather than underground wells which are very rare in the area. The construction of Hafirs particularly its size, distance factor and location indicated that pastoralists acquired knowledge even about geographical setup (physical and human aspect) in the area. This paper argues that pastoralist were the earliest group who use the system of water harvesting techniques at least in Gedarif. It has been observed that Hafirs often located near or at the end of seasonal streams with the average distance of about 22.3 km between each (Lebon, 1965). By so doing pastoralist ensure the continuity of Hafir as essential source of water and the distance help in reducing degradation around water points. In drinking management, pastoralists select the most suitable time for grazing especially during the dry period. Usually pastoralists prefer evenings and mornings for grazing to avoid high temperature during midday. The philosophy behind selecting this time is to minimize drinking water, conserving resources and above all avoiding high temperature which has negative impact on female fertility, especially camel. Therefore, during the hottest months locally known as (Manzil El Traya (see figure 4) most of the pregnant animals shade under large trees to avoid ultimate abortions. To ensure the sustainability of water sources livestock have to be watered on a regular basis, so in rainy season, where there is plenty of water pastoralists used to water their animals twice a day and to once a day in summer. The interval in drinking management depends upon the availability of water and the structure of animal in the herd. Therefore, when shortage of water becomes acute, priorities were given to lactating and pregnant females and sensitive animal have to leave Butana early (sheep and cattle) usually at the beginning of January.As indicated, water is the critical factor in drylands; therefore, pastoralists who are highly sensitive to the climatic condition, developed their own techniques to ensure optimal use of rains. They have adopted simple methods for forecasting the climate known locally as (Manazil El Sana) year calendar. The general idea of it is the division of the whole year into 28 groups (Manzil) each of which has 13 days except Manzil of El Jabha is 14 days (see figure 4). This division is based on the appearance of some known stars. Moreover, the year has three major groups known as Ains (Arabic for eye). These three Ains are Ain Kharif (eye of rainy season), Ain Seif (eye of summer) and Ain Shitta (eye of winter). This system helps them in selecting the suitable time for grazing and farming. Based on the discussion pastoralists mentioned that before two days of the new coming Manzil (interference), known locally as Mashbak has no zero doubt leads to rains. They will expect good rainy season if the earliest showers start heavily, longest winter and early appearance of some special stars, insects and plants.

| Figure 4. The Folk Calendar for the Year |

6. Institutional System and Acquiring of Land Strategy

- Adoption of communal institution system handles all matters related to land access and use is an essential strategy behind securing livelihood and having peaceful life in drylands. The system is based heavily on trusteeship, respectfulness, and both boundaries and socio-cultural networks are fuzzy (Scoones, 1995; Toulmin, 1995). Major of its responsibility is to enforce and implement legislations regarding natural resource management on behalf of the government and guarantee user rights for every member of the group as well as for future generations (Swift, 1995). Pastoralists are unlikely to favor exclusive rights; for them territorial boundaries should remain fuzzy and negotiation over access should remain a permanent process in which individuals or user groups re-evaluate their share of pastoral resources and their particular level of control over strategic resources (Mwangi & Dohrn 2006). In Sudan, the system of communal or customary rights is known locally as Dar in the eastern states or Hakura as in Darfur (means a homeland). Within the (Dar) each member or group would maintain primary rights of access to use land for farming and herding within the territory under the system of native administration Elidara Elahlia (the system governs all matters regarding communal rights). Generally it consists of three administrative tiers. They are (1) Nazirs who are in charge of the entire tribal administrative and judicial affairs; (2) Omdas those who assist Nazirs and with responsibility over tribal subsections; and (3) Sheikhs who are the village headmen. All these tribal leaders work in harmony to control and distribute land fairly (in principle) to all members and resolving disputes among their followers as well as between local and outsiders (El Hadary, 2007). Based on this hierarchy most of the problems are solved locally by Sheikhs at the village level while the multifaceted issues are transferred to higher levels of Omdas or Nazirs. The tribal leader is considered as the most essential character and so his words must be respected by all members. He also has a right to grant land for nonresident tribes (outsiders) particularly during crises under the agreement between two parties. For example, if one tribe faces a problem such as shortage of water, the other with sufficient amount can open its Dar to the needy group. This is usually under the control of the host tribal leader who determines time, place and number of days to stay. It is worth nothing to note that the system of native administration had played very vital role in settling disputes and reducing conflict. Time factor, continuous negotiations and use of social network were methods used to minimize risk and solve conflict.

7. Sudanese Pastoralists’ Local Knowledge under Threat

- During the last five decades Sudanese pastoralists’ local knowledge in rangeland management has become less efficient. Factors such as lack of rains, change in climate, population growth, and ineffective state intervention (marginalization) have repeatedly been blamed. Pastoralists in Gedarif and might be the case for the whole country cited that change in communal land ownership since 1970 into an open access or individual rights was behind the disturbing local knowledge-based range management strategies. This is completely different from the findings given by (Fernandez-Gimenez, 2000) who mentioned that changing climate (fewer rains) and declines in soil fertility (the soil getting "old") were behind the disturbance of pastoral ecological knowledge in Mangolia.In Sudan, the introduction of Unregistered Land Act of 1970 was held responsible behind disturbing the communal land ownership, increasing insecurity in land tenure, creating severe competition in rangeland, ecological degradation and speeded up the rate of conflict in most pastoral area of the country (El Hadary, 2010). According to this act all unregistered land (pastoral area) throughout the country has to be registered under the name of government property (for more details see El Hadary, 2010). This act provided a legal basis for land grabbing and has paved the way for planned as well as unauthorized expansion of commercial agriculture over pastoral lands (El Hadary, 2010). In adding salt to injury, the act was followed by abolition of native administration, an indigenous institution which was customarily responsible for controlling land (ownership and use) and resolving conflict. The system is still in place and the government has recently passed a law for its reinstatement to enable them to participate more effectively in resolution of conflict situations. But it has been accused as being politicized and affiliated to the government rather than to their people. The native administrators are today seen as government officials who gave little consideration to the rangelands, failing to represent the interests of pastoral people and are more accountable to the government than the people (Pantuliano, 2010). Changes in land tenure system coupled with weakening of native administration have put some remarkable changes in communal land rights all over Sudan, with paramount effect in Gedarif state. As a consequence, large productive areas have been taken from pastoral communities and vested to the investors, merchants, or to the people affiliated or close to the government. 2, 600, 000 hectares were given to foreign investors for commercial agriculture (Babiker, 2011). Grab- bing pastoral land is not limited to Sudan; it has become a trend in Africa. In Ethiopia for example, three million hectares were given to 1,300 foreign investors (the majority from India, China, Europe and the Middle East) with licenses for commercial farms (Graham et al., 2009). According to Gataly (2010) there are three forms of land-grabbing experienced in East Africa in recent decades via what is called “legal theft.” During the privatization process; through “agrarian colonialism” by States and commercial agro- businesses; and the acquisition of wildlife-rich range areas by entrepreneurs practicing a sort of “environmental imperialism” to create private game parks and high-end tourist attractions. Gefu (1991) has observed the same phenomenon in Nigeria where pastoral land has been taken for rapid expansion of agriculture leading to pastoralists’ crises. In Northern Nigeria Fulani pastoralists are faced with up to 8-10% decline in their rangeland following the appropriation by Hausa farmers (Mwangi & Dohrn 2006). According to Unruh (1995) in Somalia, the state favoured crop cultivation has, in many locations decreased the ability of pastoralists to reproduce itself, increased land degradation, resource use conflicts, decline pastoral production and increased impact on local institutions, which in many cases regulated rational resource access and use. According to (Butcher, 1994; Hogg, 1997) like many African pastoralists, the Borana and Afar have lost their important grazing land due to State development policies, which has increased their vulnerability to drought. Galaty (1994) have reached the same conclusion as he stated that recently, rangeland in Kenya went through a progressive process of privatization which is supported by the tragedy of the commons idea. Specifically in Gedarif unorganized expansion of both rain-fed mechanized farming and irrigated schemes have expanded rapidly, usually at the expense of pastoral communal land rights. Recently, around 70% of the total area is under mechanized farming. This, coupled with the establishment of irrigated scheme such as Rahad in 1970 and Halfa scheme in 1964, cut million hectares of rich pasture land and deprived pastoralist from accessing water in river (Atbara and Rahad) during dry seasons It is important to note that the grazing line which is made to separate farming (in the south) from grazing activities has been shifted to the far north (pastoral area). Nobody is held responsible but some voices under the table blamed and accused the lobby of the big farmers in Gedarif. Not only have that, the historical animal routes, maraheel, which were used to facilitate the seasonal movement been closed. In Gedarif state, six out of eight animal corridors which organize pastoral mobility are closed, or their limits are not clear and the remaining two have become risky, too narrow and no services are provided along them (figure 3 ). Land is everything for pastoral people (livelihood, credit, dignity, wealth, and social peace); losing these means losing everything. Thus, it is not surprising to have them fighting against the successive government that fails to address their needs and grievances. Therefore, most pastoral areas especially in Africa have witnessed severe conflicts and bloodshed. In Sudan, pastoral land has become an arena of violence such as in Darfur in western Sudan or Gedarif in the eastern Sudan which is on the “waiting list” since no serious action has been taken until now to address the livelihood insecurity of pastoral communities (El hadary, 2010). Although the root causes of this problem is often more complex than it initially appears and that in many cases it is obstacles to the safe and free movement of livestock that is the starting point (De Jode, 2010) As previously stated, the rapid expansion of unauthorized mechanized farming into available range resources is the main factor behind the escalation of conflict between farmers and pastoralists in Gedarif. During the dry season, pastoralists are forced to move to the southern part due to the scarcity of water in the north. This is considered as the harvesting time of crops; therefore, farmers do not allow pastoralists to pass by although in principle they have the right to use their traditional corridors. As a matter of survival, pastoralists are forced to graze their animals inside the schemes causing severe crop damage and thus conflict arises sometimes leading to bloodshed. The (UNEP) cited in (De Jode, 2010) has called for a moratorium on the expansion of large mechanized farms in Sudan’s central semi-arid regions, sounding a warning that it was a “future flashpoint” for conflict between farmers and pastoralists. A conflict also occurs among herders mainly between those who have historical land rights and those who lack it, whereby the article refers to them as outsiders or new comers. Confrontations over access to grazing resources are becoming more frequent and turning bloody. The conflict between local groups in Butana and Fellatta and Rashida are best examples. Nonresident tribes (outsider) pastoralists believe that they can graze anywhere in Butana based on the land Act 1970 and they are justifying their rights by paying taxes to the government for this purpose. On the other hand, local people in Butana still respect their traditional rights and believe in the system of tribal leaders. The weakening of native administration by the government since 1970 has made the traditional mechanisms for conflict management more and more ineffective (Niamir-Fuller, 1999; Blench, 2001; El Hadary, 2010).To overcome this harsh condition pastoralist with the help of their local knowledge developed a new coping strategy. Instead of taking animals to the water resources, such services are being transported to livestock (the author named it reverse mobility). It has been observed that in each village there are big trunks for carrying water from the available water sources (urban centers, rivers and wells) to the area needed. This new measures have challenged the assumption which says pastoralists are ignorant and passive in response to hazards. On the other hand, it shows that pastoralists have the ability to use their local knowledge to overcome current constraints.

8. Lesson Learnt

- The Sudanese experience offers several lessons about the role played by pastoralists’ local knowledge in rangeland management. First and foremost it rejects the notions which say pastoralists are ignorant and their communal grazing often destroys the environment. The article provides numerous examples to dispel these misconceptions. Despite these facts, still most of the planners and decision makers believed in such notions and considered privatization (grabbing pastoral land) of communal land as an ideal solution. More research is needed to calculate the benefits and losses from the conversion of pastoral land into commercial activities. It seems the outcome is less high if socio-ecological impact is considered. Four points need to be put in place of why planners prefer such conversion. First, is related to the influence of the inappropriate theories like of Hardin; second, to the incentives or pressure made by international organizations such as World Bank to modernize agriculture in developing countries; third, to the interest of the winners of “development” such big companies, merchants and government loyalties who benefited from highlighting that communal right hinder the process of development; and finally, to the limited representation of pastoral people in political arena thus their voices are hardly being heard. Our data has shown that pastoralists acquired comprehensive knowledge specifically about the ecological condition of their surrounding environment through repeated experiences. This knowledge is strongly reflected in range management and in their adaptation to drylands. Adoption mobility and its related activities under the flexible tribal system are considered as efficient strategies to cope with high risky environment of the drylands. By so doing, pastoralists not only survive in securing their livelihood but also conserve their surrounding environment. This implies that pastoral local knowledge, if enhanced and well managed can be able to participate in solving the current global problems such as food insecurity, climate change, degradation, desertification, regional peace and poverty. Therefore, planners and decision makers need to incorporate pastoralists’ local knowledge in developmental policy to ensure sustainable development. Moreover the system of managing natural resources communally under tribal system should be improved. This system has proven its efficiency in controlling land and avoiding conflict over grazing resource up to its weakening in 1970s. Since then most of pastoral areas have witnessed socio-economic instability, ecological degradation and conflict. The paper found evidence that herders' ability to make full use of their ecological knowledge is under threat due to irrational developmental policy that led to sharp decline in pastoral mobility. Factors such as lack of rains, soil degradation and climatic change have to be blamed for decline in range production. Without ignoring the role of these factors, the Sudanese experience has shown that privatization of communal land ownership or changing it into open access under the process of market economy are the major driving forces behind the deterioration in range productivity. Lack of documentation, inequality in access and distribution and gender biased are some limitations in pastoralists’ local knowledge. It is not clear that pastoral communities in Sudan are aware of the current climatic change or not. As in the discussion, less attention is paid to this issue as most of people interviewed shared a common idea that fluctuation in rains is part of their environment and they are adapted to it. This doesn’t mean that they are incorrect, might be due to the lack of their global thinking as always makes them care about their surrounding environment. Therefore, there is a need to show them that climatic change has become a reality and should be contextualized in their local knowledge. This article calls for the possibility of linking both traditional knowledge and modern science. Therefore, more research is highly needed to answer the fundamental question: Can local knowledge and science work together?

9. Conclusions

- The study concludes that the notion which viewed pastoralists as ignorant and irrational is no longer valid and needs to be revised. The Sudanese experience has shown that pastoralists through direct relation with plants, livestock, and landscape have acquired and accumulated concrete knowledge on ecological condition, climatic characteristics and animal behaviour. Whatever the term being used, indigenous knowledge or local knowledge, and ecological knowledge, this knowledge is strongly reflected in their herding practices and has proven its efficiency in managing rangeland. This useful knowledge led pastoralists to adopt opportunistic tracking approach as an adaptive strategy to cope with harsh and risky environment of the drylands. However, since 1970 pastoralist in Gedarif state as well as in the whole country can no longer make full use of their local knowledge. State intervention in rangeland often ignored the importance of pastoralists’ local knowledge in securing the livelihoods and conserving dryland environment. Changing land tenure system from communal ownership to open access or individual rights (privatization process) has disturbed the mobility, the backbone of pastoral production, and the main source of accessing knowledge. Grabbing pastoral land and vesting to foreign investors for commercial farming has become a new trend across most of the African countries. Socio-economic illness, poverty, conflict, resource degradation are becoming inevitable consequences. Therefore, there is an urgent need to recognize the importance pastoralists’ local knowledge and must be incorporated in range development if the state is looking for sustainable development. Without listening and learning from “traditional” pastoralists any effort to tackle the current global challenges such as food insecurity, regional peace and environmental degradation would at best be wasted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Authors wish to thank University of Khartoum, Sudan for funding this project and the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) for providing an opportunity through USM fellowship.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML