Mohammad Basir Uddin 1, Mujibul Hoque 2, Md Manajjir Ali 1, Afiqul Islam 3, Md Rahimullah Miah 4

1Department of Paediatrics, North East Medical College Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh

2Department of Paediatrics, Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh

3Department of Paediatrics Haematology and Oncology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Department of IT in Health, North East Medical College and Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Mohammad Basir Uddin , Department of Paediatrics, North East Medical College Hospital, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Background: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer. It constitutes approximately 31% of cancers in children below 15 years of age and approximately 77% of all cases of childhood leukemia. Abandonment is one of the most important causes of treatment failure in ALL in developing countries. Objective: To determine the percentage of abandonment and outcome of induction chemotherapy among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Methodology: This prospective, observational study was conducted in the Department of Paediatrics, Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College Hospital, Sylhet over a period of 2 years from 1st July 2014 to 30th June 2016. After admission thorough, physical examination of suspected ALL patients was done meticulously. If clinical features and blood picture suggested leukemia, then bone marrow aspiration was done to confirm the diagnosis. A total 33 diagnosed ALL patients were selected as per inclusion and exclusion criteria. Modified UK-ALL 2003 induction protocol, regimen-A was given for 13 patients and regimen-B was given for 9 patients, remission was assessed by doing morphology of bone marrow aspiration at day 29. Those who refused to start induction chemotherapy or not completed induction chemotherapy was categorized as abandonment and reasons for abandonment were identified through appropriate questioning and discussion. Remission rate was considered as primary outcome. Results: Among recruited 33 ALL patients in this study 18 (54.5%) patients were male and 15 (45.5%) female. Mean ± SD age was 5.28 ± 3.42 years with age range 15 months to 12 years. Out of 33 patient’s cumulative treatment abandonment before and during induction were 14 (42.42%), cumulative death before and during induction 5 (15.16%), 14 (42.42%) patients completed induction among them 12 (85.7%) patients achieved remission and continued treatment, 2 (14.3%) patients fails to achieve bone marrow remission. Most important cause of abandonment was that they can’t afford to treat. Conclusion: There was high abandonment and treatment related mortality; however, majority of the patients who continued treatment achieved remission at the end of induction.

Keywords:

Abandonment, Outcome, Induction chemotherapy, Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Cite this paper: Mohammad Basir Uddin , Mujibul Hoque , Md Manajjir Ali , Afiqul Islam , Md Rahimullah Miah , Abandonment and Outcome of Induction Chemotherapy in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Research In Cancer and Tumor, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2021, pp. 8-14. doi: 10.5923/j.rct.20210901.02.

1. Introduction

Leukemias may be defined as a group of malignant diseases in which genetic abnormalities in a hematopoietic cell give rise to an unregulated clonal proliferation of cells. Leukemia accounts for about 31% of all malignancies in <15 years of age. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) accounts for about 77% of all cases of childhood leukemia. [1] A sharp peak of ALL incidence is observed at 2-5 years of age. [2] There has been a gradual increase in the incidence of ALL in the past 25 years. [3] ALL occurs more in boys than in girls at all ages. [4]Incidence rate of ALL from many developing countries in Asia are unavailable as national cancer registries are not established in these countries. [5] There is no exact data on prevalence, treatment outcome of ALL in Bangladesh. Compared with the 1970s; the outcome today for children with leukemia has improved dramatically. Numerous high quality randomized controlled trials have shown that over 85% of children can now be cured. [6] In contrast, in the developing world, cure rates are less than 35% in part because of abandonment of treatment, and/or lack of dedicated, multidisciplinary Paediatric oncology units. [7,15]Almost 80% of children with cancer in resource- rich countries can be cured by timely, intensive multimodality treatment and robust supportive care. However, only 20% of the world’s children with cancer live in these countries, the remaining 80% reside in resource-poor nations and have a substantially lower chance of survival. [8] Abandonment of treatment, a severe form of non-adherence, is one of the most common reasons for treatment failure in ALL in developing countries, affecting up to 50-60% of cases. Abandonment is defined as the ‘‘failure to start or complete [potentially] curative treatment’’. [8] Therapy abandonment is often cited as an important reason for inferior survival outcome in childhood cancers in resource constrained nations. There is extremely scanty data addressing the pattern and impact of abandonment on outcome of childhood ALL from India and other Asian developing countries. [16]The International Society of Paediatrics Oncology (SIOP), Pediatric Oncology Developing Countries (PODC) abandonment of treatment working group declared that treatment abandonment can no longer be ignored by the international pediatric oncology community. [8] The phenomenon of abandonment is a significant problem in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs); in some contexts, it constitutes the most common cause of treatment failure. Many reasons for abandonment have been cited, including a lack of financial resources, poor perception regarding curability, cultural factors, belief in alternative medicine, fear of treatment toxicity, inadequate care on the part of health care providers, and decreased awareness of aid programs. [9] Various efforts in low and middle income countries (LMICs) have decreased abandonment rates, including providing financial support, adapting treatment protocols based on a family’s financial resources, providing parental education, and establishing a social work program. [10]Treatment of childhood ALL consist of general supportive care, specific treatment-chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Intensive chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment. Chemotherapy regimen includes induction of remission, consolidation, intensification and maintenance therapy. CNS prophylaxis generally provided in each phase. [1,17,18,19] The initial response to remission induction therapy is one of the most important prognostic factors in ALL. Patients who respond slowly have a high risk of relapse. [11,12,13] Those who failed to attain complete remission within 4-6 weeks of treatment have particularly miserable prognosis. [14]Outcome of patients with ALL is related not only to the leukemia itself, but also to infectious and toxic morbidities and mortality. This is especially true during induction therapy and has been demonstrated by a study from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital which concluded that infectious causes contributed to 80% of the deaths observed in children with ALL during the induction phase. There are few data on ALL outcome of early therapy from low and middle- income countries. [5]Like other developing countries Bangladesh has also inferior survival rates and more abandonment than developed countries. To see the abandonment and outcome of induction chemotherapy in childhood ALL with risk stratified regimen, this study had been conducted in the Department of Paediatrics, Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College Hospital.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective observational study was conducted in inpatient Department of Paediatrics, Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College Hospital over a period of 2 years from 1st July 2014 to 30th June 2016 after obtaining approval from ethical committee of Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College. A total of 33 cases were studied. Age 1 year to 12 years and all newly diagnosed cases of ALL are included in the study. Relapse cases of ALL and patient, who had received any chemotherapy of ALL elsewhere, are excluded from the study. Remission was defined as < 5% leukemic cells by morphology in the bone marrow smear at day 29. After admission into the Department of Paediatric, Sylhet MAG Osmani Medical College Hospital, Sylhet thorough physical examination of suspected ALL patients were done meticulously by the researcher himself. If clinical features assumed ALL then first of all routine examinations like CBC, PBF, and X-ray chest was done. If blood picture suggested leukemia, then bone marrow aspiration was done to confirm the diagnosis. After confirmation of diagnosis pre treatment evaluation was done, including CSF study, serum LDH, urinalysis, renal and hepatic function tests, serum electrolytes, serum calcium, serum inorganic phosphate and serum uric acid. ECG and echocardiography were done in high risk patients. Blood and urine culture as needed. Counseling was done regarding nature and future of the disease, available treatment, duration and probable cost of the treatment, outcome and complications. After counseling those refused for treatment and those who discontinue treatment shortly after starting chemotherapy they were categorized as abandonment and reasons for abandonment was identified through appropriate questioning and discussion. For each child a pre-designed questionnaire was prepared which include age, sex, nutritional status, parental education, socio-economic status like monthly income of parents, anthropometric assessment and clinical features at presentation. All the information captured and recorded in questionnaire.Therapy was started after risk stratification; regimen A was given for standard risk patients those age >1yrs to 9 years or initial WBC count <50,000/cumm and regimen B was given for high risk patients those age 10 years and more or initial WBC count ≥50,000/cumm.Before starting chemotherapy, all patients received hydration, alkalinization with sodium bicarbonate for forced alkaline diuresis and allopurinol to prevent or minimize acute tumor lysis syndrome. All supportive care including oral and anal care was provided.Patients were stabilized hemodynamically by giving packed cell transfusion if Hb% <8 gm/dl, platelets transfusion when the platelets count below 10,000/cumm or patients with active bleeding. For febrile neutropenia Inj. Cefipime 150 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses and Inj. amikacin 15 mg/kg day in two divided doses were started as empirical therapy. Meropenem was started in resistant infections. Treatment was given by modified UK-ALL 2003 protocol using four drugs induction therapy (5 weeks) with vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 weekly I/V, dexamethasone (6-10 mg/m2) daily orally, L-Asparaginase 6000 IU/m2 every alternate day 9 doses I/M and Daunorubicin 25 mg/m2 weekly I/V in regimen B patients. Intrathecal cytarabine, hydrocortisone and methotrexate were given on day 1, 8, 15, 28.Morphology of bone marrow aspiration was done on day 29 to see the status of remission.During induction therapy weekly CBC, liver function and renal function tests were done. Remission status was also assessed by physical examination and laboratory evaluation. All patients were followed up regularly and recorded in questionnaire.

3. Results

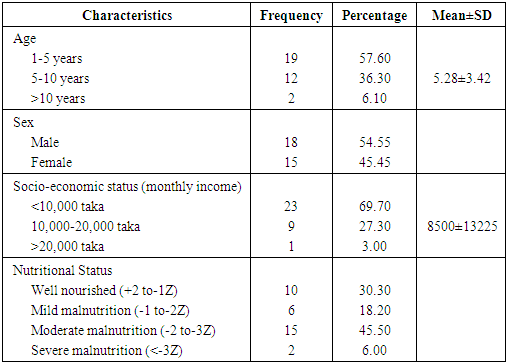

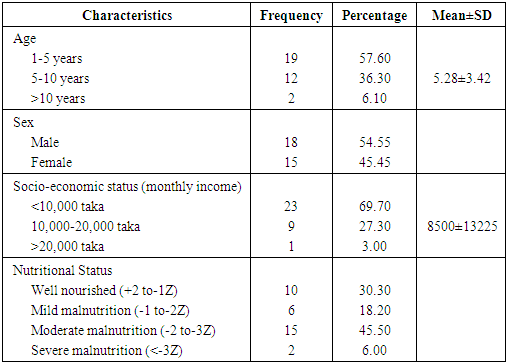

Thirty-three patients with acute lymphoblastic Leukemia were included in the study, of which 18 (54.5%) patients were male and 15 (45.5%) female, male female ratio was 1.2:1. Most patients were in the age range of 15 months to 12 years. Socio-demographic characteristics of the enrolled cases is shown table 1. Cumulative treatment abandonment before and during induction were 14 (42.42%), cumulative death before and during induction 5 (15.16%), 14 (42.42%) patients completed induction among them 12 (85.7%) patients achieved remission and continued treatment, 2 (14.3%) patients fails to achieve bone marrow remission. Most important cause of abandonment was that they can’t afford to treat.Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the patients (n=33)

|

| |

|

The mean age of the patients was 5.28±3.42 years. Male female ratio was 1.2:1. Majority of patients were poor. Among 33 patients 69.70% (23) were malnourished, 2 cases were severely malnourished. Table 2. Symptoms and signs of ALL patients at diagnosis

|

| |

|

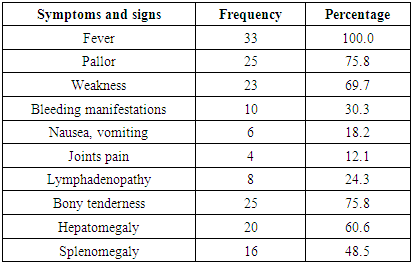

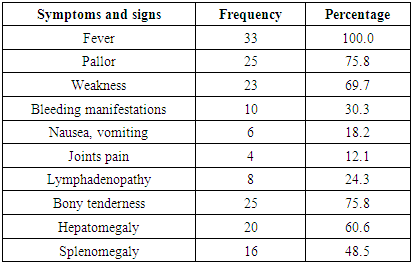

Fever and pallor were most common symptoms, fever was found in 100% cases. Among physical signs bony tenderness were found in 25 cases (75.8%), hepatomegaly in 20 cases (60.6%) and splenomegaly in 16 cases (48.5%).Table 3. Hematological parameters at initial diagnosis

|

| |

|

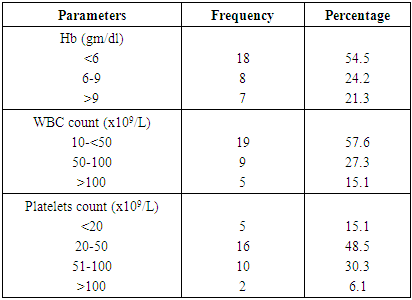

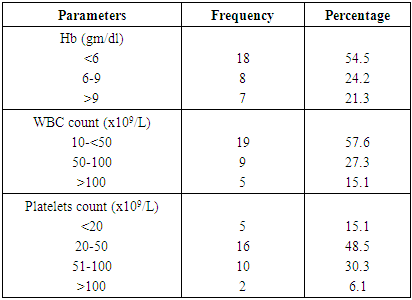

Among 33 patients 18 (54.5%) patients were severely anemic at diagnosis, 14 (42.4%) patients initial WBC count >50,000/cumm indicating high risk ALL. Almost 94% cases platelets count <100,000/cumm.Table 4. Percentage of abandonment (n=14)

|

| |

|

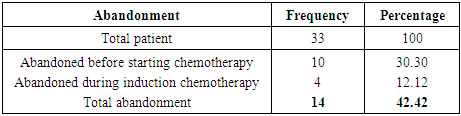

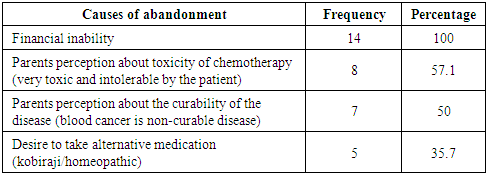

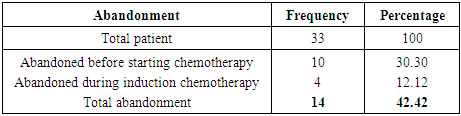

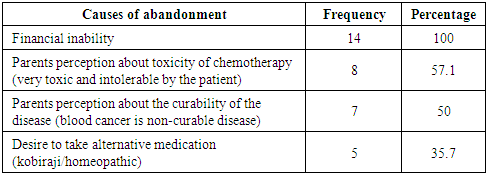

Out of 33 patients 14 (42.42%) abandoned treatment.Table 5. Causes of abandonment

|

| |

|

The most common cause of abandonment was financial inability 14 (100%). More than 50% parents’ percepts that chemotherapy is very toxic and intolerable by the patient. Half of the parents believe that blood cancer is not a curable disease. About 35.7% desired to take alternative medication.Table 6. Outcome of induction chemotherapy (n=22)

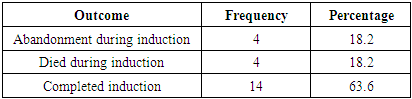

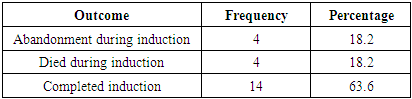

|

| |

|

Out of 22 patients 14 (63.6%) patients completed induction. Four patients (18.2%) abandoned treatment during induction. Four patients (18.2%) died during induction.Table 7. Percentage of remission (n=14)

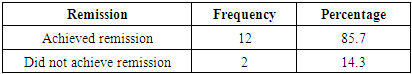

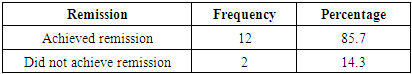

|

| |

|

Among 14 patients 12 (85.7%) patients achieved remission at the end of induction, 2 (14.3%) patients did not achieve remission.Table 8. Patients received risk stratified regimen (n=22)

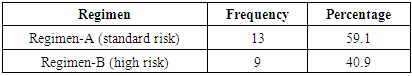

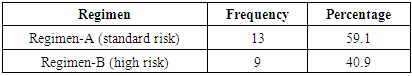

|

| |

|

Out of 22 patients 13 (59.1%) patients received regimen-A, 9 patients (40.9%) received regimen-B ALL protocol.Table 9. Outcome of patients received risk stratified regimen (n=22)

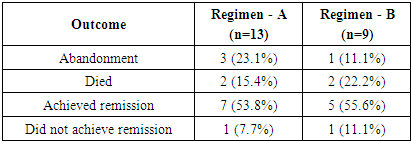

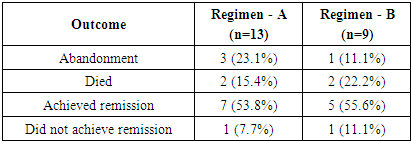

|

| |

|

Out of 13 patients in regimen-A, 3 patients (23.1%) abandoned treatment, 2 patients (15.4%) died, 7 patients (53.8%) achieved remission, and 1 patient (7.7%) did not achieve remission. Out of 9 patients in regimen-B, 1 patient (11.1%) abandoned treatment, 2 patients (22.2%) died, 5 (55.6%) achieved remission, 1 patient (11.1%) did not achieve remission.Table 10. Toxicities encountered during induction chemotherapy (n=22)

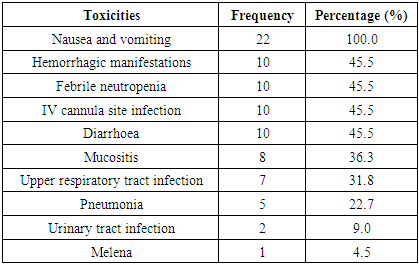

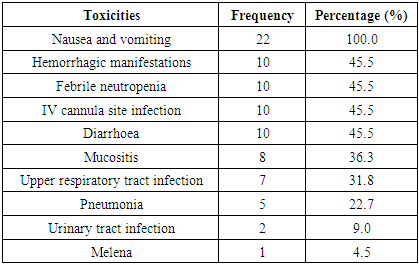

|

| |

|

Nausea and vomiting occurred in 100% patients during induction. Most of the patients developed hemorrhagic manifestations, febrile neutropenia, IV cannula site infection and diarrhea. Table 11. Causes of death during induction chemotherapy (n=4)

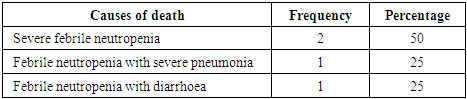

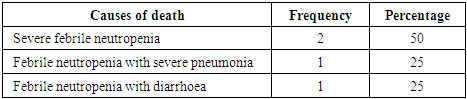

|

| |

|

During induction therapy100% patients died due to febrile neutropenia.Table 12. Distribution of the patients by outcome (n=33)

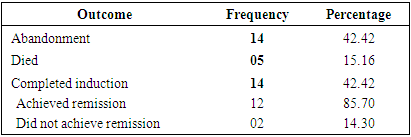

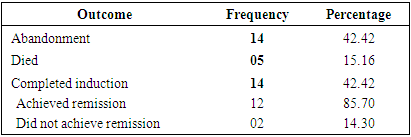

|

| |

|

Cumulative treatment abandonment before and during induction was 14 (42.42%). Cumulative death before and during induction was 5 (15.16%). Completed induction 14 (42.42%) patients among them achieved remission 12(85.7%), did not achieve remission 2 (14.30%).

4. Discussion

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer. Approximately 77% of all cases of childhood leukemia. [1] The initial response to remission induction therapy is one of the most important prognostic factors in ALL. Patients who respond slowly have a high risk of relapse. [11,12] In the present study mean age of the patients was 5.28 years. Fadoo et al [5] found that, the mean presenting age of ALL was 6.87 years that was higher than the present study because they included patients up to 18 years of age. One study in Pakistan showed mean age of the patients was 5.4 years which was almost similar to the present study. [2] In the current study male-female ratio was 1.2:1. Kliegman et al [1] showed ALL occurs more in boys than in girls at all ages. Reasons for near equality of male female ratio in this study could be multiple such as increase social awareness and less male female discrimination than in other study population. In our society during the past two decades major changes in school attendance- equal male female enrolment, high vaccination coverage and progress in female empowerment took place. These could explain the attitude changes towards female child increased admission to public hospitals. Kulkarni et al [21] showed in their study in India the male-female ratio was 3.16:1. Both studies found male predominance in childhood ALL. In the present study 70% patients belong to low income group, earning less than 10,000 Tk. per month. All the cases were from a public hospital where patients from relatively poorer section of the society vie for treatment. Bonilla et al [9] in their study showed that monthly family income was significantly related to abandonment rates.In the present study fever and pallor were most common symptoms at initial diagnosis. Fever was found in 100% patients. Among physical signs bony tenderness was found in 75.8% patients, hepatomegaly in 60.6% patients, and splenomegaly in 48.5% patients. Rana et al [2] showed 84% patients presented with pallor, 73% with fever, 86% with hepatosplenomegaly, and 57% with lymphadenopathy. Hundred percent patients in the present study presented with fever which may be due to late diagnosis of the disease.In this study 42.42% patients presented with the initial WBC count ≥50,000/cumm which was markedly higher than that reported in Western literature (17%), thus reflect to a higher tumor burden with poorer outcome. [22]In the present study cumulative treatment abandonment before and during induction was 42.42%. Fadoo et al [5] in their prospective multicenter cohort study in Pakistan showed cumulative treatment abandonment before and during induction phase was 12.8%. Kulkarni et al [16] in their study in Chandigarh, India showed out of 532 patients, 18.1% (96) patients abandoned therapy. Most abandonment occurred during induction phase. Lower abandonment rate was observed in above mentioned studies than the present study, because these studies were conducted in a specialized paediatric oncology centre where there were available facilities and financed by donations. Current study was conducted in a regional government tertiary medical college hospital with limited free oncologic treatment support; most of the parents were poor and objected to unbearable treatment cost.In this study the most common cause of abandonment was financial inability (100%). More than 50% parents’ percepts that chemotherapy is very toxic and intolerable by the patient. Half of the parents believed that blood cancer is non-curable disease. About 35.7% parents desired to take alternative medication (kobiraji/ homeopathic). Arora et al [20] in their study showed that the burden of the cost of treatment falls mostly on the family of the child and parents consistently report financial burden is the main reason for abandonment. The above-mentioned study supports the present study, because 100% patients abandoned treatment due to unbearable financial burden of the imposed treatment protocol. Sitaresmi et al [26] showed in their study abandonment rates for ALL was highest during the early phase of induction (64%). This may be related to multiple factors acting singly or in combination. These include treatment-related toxicity, painful procedures performed with inadequate analgesia and sedation, predetermined health beliefs of parent’s and lack of finances.In the present study 63.6% patients successfully completed induction, 85.7% achieved remission, 14.3% did not achieve remission and cumulative mortality rate was 15.16%. One study at Dhaka Shishu Hospital, in Bangladesh showed 76.7% patients achieved remission, 13.3% did not achieve remission and mortality rate was 10%. [23] In the current study percentage of patients achieved remission is slightly more than the above-mentioned study may be due to improving quality of supportive care, increasing awareness among health care professionals and parents but not optimal due to high abandonment and treatment related mortality. Seksarn et al [24] in their study in Thailand showed 91.8% achieved remission, 3.3% did not achieve remission. Fadoo et al [5] in their study in Pakistan showed 84.0% successfully completed induction phase and achieved remission 92% with a mortality was 11.5%. The above-mentioned studies were conducted in a specialized oncology centre with existing oncologic support. It has been observed in this study that 22 (66.7%) patients started induction, 13(59.1%) patients received standard risk regimen-A and 7(53.8%) achieved remission. Nine (40.9%) patients received high risk regimen-B and achieved remission 5(55.6%) patients. Seksarn et al [24] showed that, remission rates were 95.1% those patients received standard risk regimen-A, ALL protocol and remission rates were 87.2% in regimen-B received patients. In the present study those patients received regimen B, ALL protocol achieved remission rates were slightly higher than regimen-A patients, because more abandonment was observed in regimen-A during induction. Since immunophenotyping and molecular study were not included in the current study, this stratification however might not represent the true risk as defined in other studies. Some patients, who were defined as low risk, might actually have been intermediate or high risk.All patients had experienced toxicity during induction. The most common toxicities were nausea and vomiting, febrile neutropenia and hemorrhagic manifestations. Rana et al [2] in their study showed similar toxicities.In this study 18.2% patients died during induction, hundred percent deaths occurred due to febrile neutropenia. All patients received good antibiotics coverage. Asim et al [25] in theirs study in Pakistan showed that 52.7% deaths occurred during induction of ALL. Fadoo et al [5] in their study in Pakistan showed mortality was 11.5%. One study at Dhaka Shishu Hospital, in Bangladesh showed mortality rate was 10%. [23] In the current study mortality rate was higher than that reported from above mentioned two studies, due to lack of effective infection control measures. Infection was the major cause of death found in all studies. [5,24,25]

5. Conclusions

Abandonment rate was high and financial inabilities, misconception regarding curability, belief of alternative medicine were important causes of these abandonment. Outcome of induction chemotherapy was also good although mortality rate was higher due to high rate of infection. Infection control measures should strongly be implemented in the hemato-oncology unit to reduce the febrile neutropenic death.

Declarations

FundingThis research work is a part of MD Thesis, which was completed at Sylhet M.A.G. Osmani Medical College and Hospital, affiliated with Sylhet Medical University, Sylhet, Government of People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Data AvailabilityThe data are being used to support the findings of this research work are available from the corresponding author upon request. Competing InterestsThe authors declare no potential conflict of interests in this research work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledged the authority of North East Medical College and Hospital, South Surma, Sylhet, Bangladesh and Sylhet M.A.G. Osmani Medical College and Hospital, affiliated with Sylhet Medical University, Bangladesh for providing kind supports.

References

| [1] | David G, Tubergen, Bleyer A, Ritchey AK, Friehling E. The Leukemias. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF David G, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. India: Reed Elsevier Private Limited; 2016. P. 2437-2445. |

| [2] | Rana JA, Rabbani MW, Sheikh MA, Khan AA. Outcome of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia after Induction Therapy: 3years experience at a single pediatric oncology centre. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2009; 21:150-153. |

| [3] | Shah A, Coleman MP. Increasing Incidence of Childhood Leukemia: a controversy re-examined. Br J Cancer 2007; 97: 1009-1012. |

| [4] | Mclntosh N, Helms PJ, Smyth RL, Logan S. Forfar and Arneil’s Textbook of Pediatrics.7th edition. China: Elsevier; 2008: 982-988. |

| [5] | Fadoo Z, Nasir I, Yousuf F, Lakhani LS, Naqvi S, Belgaumi A. Clinical Features and Induction Outcome of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in a Low/Middle Income Population: A Multi-Institutional Report from Pakistan. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62: 1700-1708. |

| [6] | Mitchell C, Hall G, Clarke RT. Acute Leukemia in children: diagnosis and management. BMJ 2009; 338: 2285. |

| [7] | Kulkarni KP, Arora RS, Marwaha RK. Survival Outcome of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in India: a resource-limited perspective of more than 40 years. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011; 33: 475-479. |

| [8] | Mostert S, Arora R, Arreola M, Bagai P, Friedrich P, Gupta S, et al. Abandonment of Treatment for Childhood Cancer: Position statement of a SIOP PODC Working Group. Lancet Oncology 2011; 12: 719-720. |

| [9] | Bonilla M, Rossell N, Salaverria C, Gupta S, Barr R, Sala A, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Abandonment of Therapy Among Children with Cancer in EL Salvador. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 2144-2146. |

| [10] | Howard SC, Pedrosa M, Lins M, Pedrosa A, Pui C, Ribeiro R, et al. Establishment of a Pediatric Oncology Program and Outcomes of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in a Resource Poor Area. JAMA 2004; 29: 2471-2475. |

| [11] | Lilleyman JS. Clinical Importance of Speed of Response to Therapy in Childhood Lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia Lymphoma 1998; 31: 501–506. |

| [12] | Gajjar A, Ribeiro R, Hancock ML, Rivera GK, Mahmoud H, Sandlund JT, et al. Persistence of Circulating Blasts after 1 Week of Multiagent Chemotherapy Confers a Poor Prognosis in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood 1995; 86: 1292-1295. |

| [13] | Gaynon PS, Desai AA, Bostrom BC, Hutchinson RJ, Lange BJ, Nachman JB, et al. Early Response to Therapy and Outcome in Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A review. Cancer 1997; 80:1717–1726. |

| [14] | Schrappe M, Reiter A, Ludwig WD, Harbott J, Zimmermann M, Hiddemann W, et al. Improved Outcome of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Despite Reduced Use of Anthracyclines and Cranial Radiotherapy: Results of trial ALLBFM 90 German-Austrian-Swiss ALL-BFM Study Group. Blood 2000; 95:3310–3322. |

| [15] | Kellie SJ, Howard SC. Global Child Health Priorities: what role for paediatrics oncologists? Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 2388–2396. |

| [16] | Kulkarni KP, Marwaha RK. Pattern and Implications of Therapy Abandonment in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2010; 11: 1435–1436. |

| [17] | Molla MR, Concise Textbook of Paediatrics, 2nd ed. Leukemia. Dhaka: Child Friendly Publications; 2007. p. 592- 605. |

| [18] | Khan MR, Rahman M E. Essence of Pediatrics. 4th ed. Childhood Leukemia. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2011.p. 303-306. |

| [19] | Lanzkowsky P. Manual of Pediatrics Hematology and Oncology. 5th edition. India: Elsevier Academic Press; 2011. p.518-566. |

| [20] | Arora RS, Pizer B and Eder T. Understanding Refusal and Abandonment in the Treatment of Childhood Cancer. Indian Paediatrics 2010; 47: 1005-1010. |

| [21] | Kulkarni KP, Marwaha RK. Significant Male Preponderance in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in India and Regional Variation: tertiary care centre experience, systematic review, and evaluation of population-based data. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013; 30: 557-567. |

| [22] | Greaves MF, Colman SM, Beard ME, Baradstock K, Cabrera ME, Chen PM. Geographic Distribution of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Subtypes. Leukemia 1993; 7: 27-34. |

| [23] | Wohab AM. Immediate Outcome of Acute Leukemia Following Induction Chemotherapy in Relation to Clinical and Laboratory Profile [dissertation]. Institute of child health: Dhaka; 2015. |

| [24] | Seksarn S, Wiangnon S, Veerakul G, Chotsampancharoen T, Kanjanapongkul S, Chainansamit SO, et al. Outcome of Childhood Acute lymphoblastic leukemia Treated Using the Thai National Protocols. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16: 4609-4614. |

| [25] | Asim M, Zaidi A, Ghafoor T, Qureshi Y. Death Analysis of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Experience at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Pakistan. J Pak Med Asso 2011; 61: 666-670. |

| [26] | Sitaresmi MN, Mostert S, Schook RM, Sutaryo, Veerman AJ. Treatment Refusal and Abandonment in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Indonesia: an analysis of causes and consequences. Psycho - oncology 2010; 19: 361–367. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML