-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research In Cancer and Tumor

2013; 2(2): 38-44

doi:10.5923/j.rct.20130202.04

Epidemiological Studies of Head and Neck Cancer in South Indian Population

R. Rekha1, M. Vishnu Vardhan Reddy2, P. Pardhanandana Reddy1

1Department of Biotechnology, Mahatma Gandhi National Institute for Research and Social Action, Hyderabad, India

2Department of ENT, Osmania Medical College and Govt. ENT Hospital, Hyderabad, India

Correspondence to: R. Rekha, Department of Biotechnology, Mahatma Gandhi National Institute for Research and Social Action, Hyderabad, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this study is to identify causes, and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations, leading to head and neck cancers. Different parameters were taken into consideration and a demographic risk profile was defined as reported from a hospital-based cancer registry in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh. The study was conducted in histologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck during a period of 2010-2011. The prevalence of cancer was higher in males than females and habits like smoking, alcohol and chewing were the major risk factors. Cancer of larynx was the most prevalent in men and women.

Keywords: Epidemiology, India, Head and Neck Cancer, Risk Factors

Cite this paper: R. Rekha, M. Vishnu Vardhan Reddy, P. Pardhanandana Reddy, Epidemiological Studies of Head and Neck Cancer in South Indian Population, Research In Cancer and Tumor, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 38-44. doi: 10.5923/j.rct.20130202.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Head and neck cancer is a complex disorder that includes mostly squamous cell carcinomas that can develop in the throat, larynx, nose, sinuses, and mouth. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) remains a major clinical challenge in oncology and represents the sixth most common neoplasm in the world today.[1] About 650,000 new cases in the world are reported every year.[2] Despite advances in treatment methods for head and neck cancer, the survival rate has not been largely improved.[3] The major reason is that conventional treatment regimens are non-selective and are related with systemic toxicities.[4,5] The failure is essentially due to marked clinical heterogeneity of the biological behaviour of these tumors, resulting in the accumulation of multiple gene mutations, often different from each other tumor. In addition to the potentially substantial psychological and physiological trauma arising from any malignancy, unique quality of life (QOL) burdens are borne by survivors of head and neck cancer. These unique burdens include disfigurement of the face, distortion of speech, loss of taste and appetite, impairment of eating, severe oral dryness, and continuing stiffness of the tissues.[6] Smoking, tobacco, alcohol consumption are main risk factors for head and neck cancer.[7] Epidemiological studies also report a strong association with human papillomavirus (HPV) in a subset of HNSCC and in non-smoking cases. [8,9] In South Asian countries, the risk of HNSCC is further aggravated by smoking of bidis, [10] reverse smoking and chewing tobacco, betel quid and areca nut.[11] The prevalence of cancer is often strikingly dissimilar in different groups of population, varies greatly from one community to another, and differs in different communities in the same geographic location, depending on the practices and lifestyles of the people in that location. Moreover, differences have been observed in the etiological, clinicopathological, and molecular pathological profile in the tobacco smoking, chewing, and alcohol associated oral cancers, particularly in the Indian subcontinent.[12]To identify and quantify the etiological profile that might be implicated in a selected population, it is essential to determine the behavioral patterns, habits, customs, and environmental background of the group under study. It is necessary to identify the differences, if any, in the sites, patterns, and incidence rates of the disease amongst various communities living in geographic areas having varying patterns of climate and physical environments by identifying dietary habits, social customs, and such other factors. Many independent researchers[12-17] had reported the wide ranged prevalence of oral cancer and its risk factors in various parts of the country, but there is a scant literature concerning the risk factor profile of oral cancer patients in Andhra Pradesh. Since considerable differences exist in the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, diet, literacy, social status, and availability of the services in the state of Andhra Pradesh compared to the other states,[12] we attempt to define the demographic, risk profile, and stage at diagnosis among the group of HNSCC patients reported in one hospital-based cancer registry in Andhra Pradesh during the period of 2010-2011.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

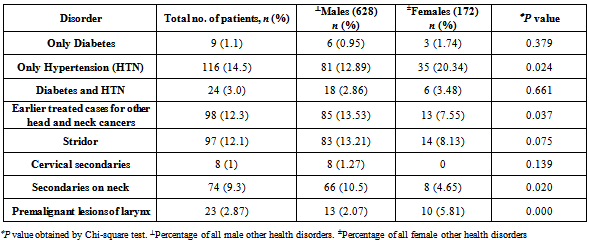

- The study population consisted of 800 patients out of which 628 (78.5%) were males and 172 (21.5%) were females. The patients had histologically confirmed diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, who reported during the period from 2010-2011 in one hospital-based cancer registry of Govt. ENT Hospital, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh. The demographic profile and clinical information obtained includes the information on age, gender, site of origin, risk factors, history of illness, clinical examination, operation notes, and mode of treatment. The site of cancer was classified (C32.0-32.9) based on the second edition of the International Classification of Disease for oncology[12,18] (ICD-02), depending on the 11 presentation sites of HNSCC: base of tongue (BOT), tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, floor of mouth (FOM), lip, gingiva, oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx, and hypopharynx. This study was approved by the Govt. ENT Hospital ethical committee. Fasting plasma glucose levels at 74-110 mg/dl and Post-prandial plasma glucose levels within 90-150 mg/dl, detected by GOD-POD (glucose oxidase-peroxidase) method, were considered as the cut-off criteria for blood glucose levels as for identifying possible diabetes in the study group [Table 3]. Blood pressure greater than 140/90 was considered a reasonable pressure level to be categorized as high blood pressure or hypertension [Table 3].

2.2. Statistical Analysis

- The data were analyzed using SPSS version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significance (P) values and Correlation values were determined by Pearson Chi-square test to assess the association of gender with age groups, habits, other health disorders, site of diagnosis. The risk factor associations were reviewed and compared with site of diagnosis and habits. P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Any P value more than 0.05 was considered non-significant in this particular study population.

3. Results

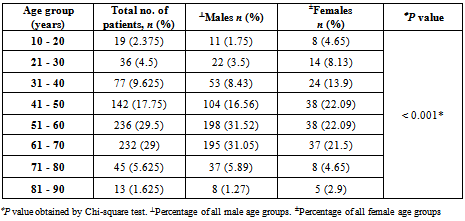

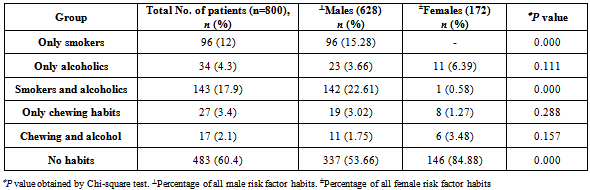

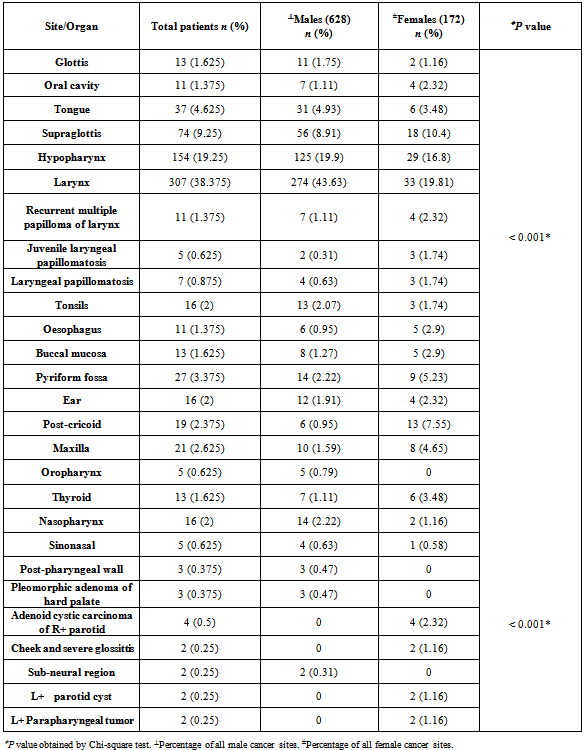

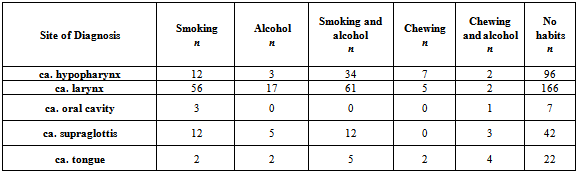

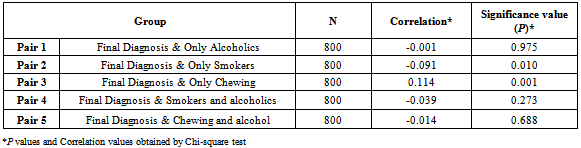

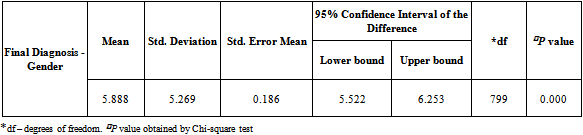

- A total of 800 cases of head and neck cancers (HNSCC) were reported during the study period. In all age groups, number of males was more than female subjects. Among both males and females, the highest incidence of HNSCC was seen within the age group of 51-60 (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. Carcinoma of larynx was the commonest cancer reported.146 females (84.88%) and 337 males (53.66%) in the study had no risk-factor habits. In males, the major risk factor habit was a combination of smoking and alcohol (22.61%), followed by only smoking (15.28%), only alcohol (3.66%), only chewing (3.02%) and the least being chewing and alcohol (1.75%). In females, the major risk factor habit was only alcohol (6.39%), only chewing (1.27%), chewing and alcohol (3.48%) followed by smoking and alcohol (0.58%) [Table 2]. P value calculations [Table 2] showed that smoking habits and a combination of smoking and alcohol habits were statistically significant in this population, whereas alcohol habits, chewing habits and a combination of chewing and alcohol habits were non-significant (P > 0.05).The most common health disorder other than HNSCC was stridor accounting to 15.37%, followed by hypertension (14.32%), secondaries on neck (9.25%), treated earlier for HNSCC (4.6%), diabetes (2%) and least being cervical secondaries (1%) in the overall study population. A combination of hypertension and diabetes accounted to just 1.6% [Table 3]. In males, the most common health disorder other than HNSCC was being treated earlier for HNSCC (13.53%), stridor (13.21%), hypertension (12.89%), secondaries on neck (10.5%), cervical secondaries (1.27%) and diabetes (0.95%). A combination of hypertension and diabetes accounted to 2.86%. In females, the most common health disorder other than HNSCC was hypertension (20.34%), stridor (8.13%), treated earlier for HNSCC (7.55%), secondaries on neck (4.65%) and diabetes (1.74%). A combination of hypertension and diabetes accounted to 3.48%. There were no reported cases of cervical secondaries in females.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The present study was a retrospective and hospital-based study which focused only on the histologically confirmed cases of HNSCC patients. It was observed that males outnumbered the number of female patients. The most common risk habits were smoking, alcohol consumption, chewing tobacco and a combination of these habits. Burning tobacco releases polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are known carcinogens. These carcinogens reach epithelial surfaces through smoke or get dissolved in saliva. Breakdown of these carcinogens by aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase produces the actual carcinogenic epoxides that bind to the DNA and RNA molecules.[21] Tobacco smoke acts as a direct carcinogen - delivery system, with alcohol providing more ready access to cells for tobacco carcinogens via its solvent properties, and more DNA damage. Both alcohol and tobacco increase the risk likelihood of promotion because of their capacity to damage and kill cells, as a result of oncogene mutation, or loss of tumor suppressor genes.[22] Males were more prone to cancer, possibly as they were used to the risk factor habits over a long time and more quantity, when compared to females. This study is a hospital-based one and it reflects results only for a specific population. These results cannot be anticipated for general population. Maximum number of patients, both males and females were in the age group of 51-60 years, followed by a close margin in the 61-70 years age group. All the habits were found to be pre-dominant in males than in females. Almost 60% (n = 483) of the patients did not have any of the risk factor habits. This shows that there are many different factors responsible for causing cancer, other than smoking, alcohol consumption and chewing habits. The most common habit in males was a combination of smoking and alcohol consumption (23%) and in females, it was alcohol consumption (6%). Culturally toddy, an alcoholic drink is considered to be as a socially accepted drink in rural areas of South India. Women drink toddy to be relieved of body aches, have good sleep at night, and make them prepared to work on the next day.[12] The culturally accepted toddy drinking habit in females might be one of the risk factors for cancer occurrence.[19] Chewing and alcohol consumption habits were the common risk habits in females as smoking is not a culturally indulged habit in our society, whereas a combination of smoking, chewing and alcohol habits were common in males. However, it doesn’t prove that indulging in such habits will necessarily lead to diseased conditions. This is because a significant number of subjects in the present study did not indulge in any habits and were still diagnosed with HNSCC. Unfortunately, there is no adequate information about the other possible risk factors, in non-habit related HNSCC cases.Most patients belonged to a lower socio-economic status. Low socio-economic status means having less affordability to proper food and hygienic conditions, indicating poor nutrition leading to deficiencies. There is evidence that mineral and vitamin deficiencies can be associated with the risk of laryngeal cancer.[20]We are seeing a considerable number of patients with HNSCC, presenting without any known associated risk factors. However, what might be causing these cancers is still to be proven, with HPV and dietary factors being at the forefront of alternative etiological factors. Immediate approach for prevention of HNSCC via known risk factor habits should be implemented by creating awareness through educational and public programmes. Proper strategy should be followed at hospitals for recording all possible details of the disease and the patient, to help understand the variations in population and diagnosing health conditions. Counseling of at-risk population should be provided thereby ensuring early diagnosis and management.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank Dr. Laxmi Addala for her timely and unconditional cooperation and for her help with all the statistical results.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML