-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Plant Research

p-ISSN: 2163-2596 e-ISSN: 2163-260X

2012; 2(2): 1-5

doi: 10.5923/j.plant.20120202.01

Effect of Weeds on Calcies Yeild of Hibiscus Sabdariffa L in Traditional Agricultural Sector of Sudan

Ahmed M. E l Naim 1, Salheldeen E. Ahmed 1, Abdelrhim A. Jabereldar 1, Moayad M.B. Zaied 1, Khlid A. Ibrahim 2

1Department of Crop Sciences, Faculty of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, University of Kordofan, Elobeid, Sudan

2Department of Soil and Water Sciences, Faculty of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, University of Kordofan, Elobeid, Sudan

Correspondence to: Ahmed M. E l Naim , Department of Crop Sciences, Faculty of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, University of Kordofan, Elobeid, Sudan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Weeds play an important role in the proper stand establishment of the growing crop, which ultimately affect the productivity and quality at the end of the growing season. Hand hoeing is still by far the most widely practiced cultural weed control technique in field crop production throughout the traditional agricultural sector in Sudan, because of the prohibitive costs of herbicides and fear of toxic residue coupled with the lack of knowledge about their use. Fields studies were conducted at North Kordofan state, Sudan, on naturally infested fields within the same area, using three similar fields during 2007/2008 rainy season, to determine optimal weeding frequency for weeding management in two widely used cultivated varieties of Hibiscus sabdariffa L, (Elrahad and Elfashir). The majority of weeds in site were the broad leaves (dicotyledons), while grasses (monocotyledons) found in a lesser density. The dominant weed floras were Alhuskaneet (Cenchrus biflorus L), Sheilini (Zornia glochidiata L) and Alraba (Trienemara pentanture L). Weeds reduced yield of the crop by about 75 % compared to weeding twice during the season.

Keywords: Weeds, Traditional Sector, Roselle, Yield

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L) family Malvaceae, known commonly as "Karkade”. It is known under different names in different countries viz roselle, razelle, sorrel, red sorrel, Jamaica sorrel, Indian sorrel, Guinea, sorrel, sour -sour, and Queens land jelly plant (Mahadevan et al., 2009; Morton, 1987). It is an important crop in tropical and sub-tropical regions. The economical part of the plant is the fleshy calyx (sepals) surrounding the fruit (capsules).In Sudan fully developed fleshy calyx is peeled off from the fruit by hand and dried naturally under shade to give the dry (calyx), which is the consumable product. The plant, normally grown as annual plant, is 0.5 to 2 meters in height. It has a bushy shape with some what dense canopy of dark green leaves. The colour of the calyx plays an important role in determining the quality of the crop. The crimson red colour is the characteristic and most popular and desirable colour of roselle while other shades and colors exist, including the white or greenish white colour. It is an important cash crop in Western Sudan, particularly in Northern Kordofan State where the largest area of roselle is grown, especially in Elrahad and Um- Rawaba areas. The crop is mostly produced in traditional growing conditions by small-farmers, depending on rainfall and natural soil fertility without using chemical fertilizers or insecticides (El Naim and Ahmed, 2010). Roselle has many industrial and domestic uses. Locally, in the Sudan it is used as a beverage, where the dried calyx is soaked in water to prepare a colorful cold drink. Traditionally the product has been used for medicinal purposes for relief of sour throat and for healing wounds as an anti-septic (Aziz, 2007). Mahadevan et al (2009) reported that, in many parts of the world leaves is consumed as green vegetable and the stem is used as a source of pulp for paper industry. Seeds used as a poultry feed and as an aphrodisiac coffee substitute (Anonymous, 1959, Khidir, 1997). The total cultivated roselle area in Sudan during the 99/2000 season was estimated as 140,000 ha (El Naim and Ahmed, 2010). The main production comes from Western Sudan States, and the most of the exported crop is grown in the Eastern Kordofan localities. Roselle is also scattered in the southern region and south Fung area and recently at Abu Naama in the rainfed central clay plains of Sudan (Mclean, 1973). Weeds have been defined as higher plants in the Agro-ecosystem which are not sown, undesired ‘’ out of place’ or generally as plants which do more harm than good, (El Naim and Ahmed, 2010). They lead to direct yield losses through competition with the crop for water, nutrients, light, space and/or carbon dioxide. This degree of damage is mainly a function of their number, biomass and leaf area –index as compared with that of the crop. Weeds have different competitive abilities, which determine their performance and potential of damage in given situations; most important are vigor, growth habit, seed production, regenerative capacities and time of germination. In addition to competition, weeds can interfere negatively with cultural and harvest practices and may be poisonous and /or harbor pests and diseases. On the other hand, .weeds may have positive properties, when stabilizing the soil adding humus and nutrients to the soil (mainly) and extracting otherwise unavailable nutrients. In addition they might be alternative hosts for predators and used as sources of food, fodder, Fuel, .building material and for other technical purposes.(Weiikersheim, 1991). Groundnut for example is a field crop, but if it germinates in the subsequent culture, it is regarded as undesired ordinary weed. The objectives of this study were: to investigate the effect weeding frequencies on yield and Harvest index of roselle grow in sandy soil of Kordofan, Sudan in rain-fed.

2. Materials and Methods

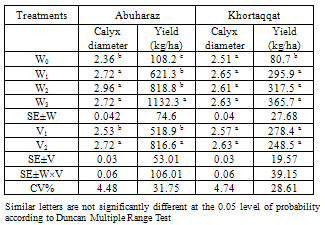

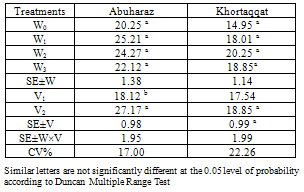

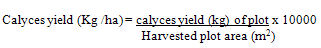

- A field experiment was conducted during season 2007/ 2008 under rainfed conditions in two fields naturally weeds infested in North Kordofan State, Sudan. The fields were: Abu Haraz, and Khor taqqat. The experiment was laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replications. The plot size was 5×4 meters consisted of 7 rows with 5 m along. The weeding treatments consisted of four levels (no weeding, weeding once (at 2weeks), weeding twice (at 2 and 3 weeks) and weeding three times (at 2, 4 and 6 weeks after sowing) designated as W0, W1, W2 and W3 respectively. Two widely used cultivated varieties of roselle (Elrahad, and Elfashir) were used in the experiment, designated as V1 and V2, respectively. Sowing dates on 11th of July. Seeds were sown on rows at spacing of 70 cm apart and 40 cm within row, five seeds were placed in each hole. The plants were thinned to two plants per hole, two weeks later. The weed species found at each site were recorded at 15 DAS and then continued as interval of 14 days. Weeds counts made by placing the quadrate (0.5m x 0.5m) at random locations in plots repeated four times in order to obtain a reasonably good estimate of small weeds. The relative weed densities were calculated.A destructive sample of five plants was taken at random from the five inner rows of experimental plot at maturity to measure the following yield attributes.- Number of calyces per plant - Calyces yield per plant (g): The calyces of five plants were peeled off from the capsules by using simple hand tools. The calyces were dried under shade to constant weight, and then average calices yield per plant (g.) was determined.- Final calyces yield (kg / ha). Calculated by using the following formula:

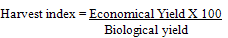

- Harvest index was determined by using the following formula:-

- Harvest index was determined by using the following formula:- Data were analyzed statistically using analysis of variance according to Gomez and Gomez (1984) procedure for a randomized complete block design. The differences of means were identified by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at P ≥ 0.05

Data were analyzed statistically using analysis of variance according to Gomez and Gomez (1984) procedure for a randomized complete block design. The differences of means were identified by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at P ≥ 0.053. Results and Discussion

3.1. Weeds and Stand

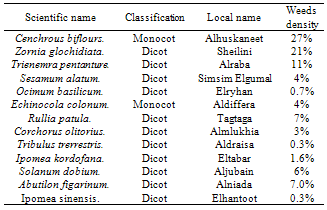

- The majority of weeds in the experimental sites were the broad leaves (dicotyledons), while grasses (monocotyledons) found in a lesser density (Table 1). The presence and absence of weed species during the growing season are presented in Table 2. The majority of weeds in the experimental sites were the broad leaves (dicotyledons), while grasses monocotyledons) found in a lesser density. The dominant weed flora infesting Roselle (Karkade) during growing season were Cenchrus biflorus L (Alhuskaneet), Zornia glochidiata L (Sheilini) and Trienemara pentanture L (Alraba). They had relative weeds density of 27%, 21% and 11% respectively. El Naim and Ahmed (2010) found that the Cenchrus biflorus L was the most dominant weed in fields of Kordofan.

|

3.2. Growth and Yield Attributes

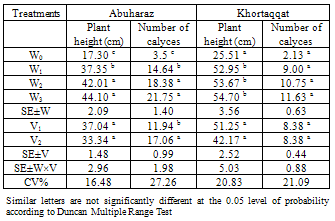

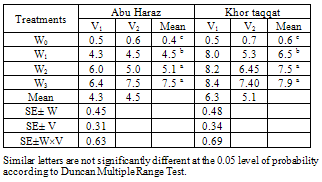

- Weeds decreased plant height (Table 2). The significant differences in plant height among treatments may be attributed to the competition of weeds for soil moisture, nutrients, light and carbon dioxide. Weeding facilitates plants to have more resources for growth, these results agreed with El Naim and Ahmed (2010) who showed that, increasing weeding times increased plant height, due to efficient weed control. Generally Elfashir variety (V2) had significantly greater plant height than (V1). Significant Differences in plant height among varieties were reported by El Naim and El Naim (2010), Cheweya (1992) and sulaiman (2005). The significant differences among weeding treatments in leaf area index (LAI) were observed in this study. Increased weeding frequencies increased leaf area index. This was due to better control of weeds. The reduced competition and increased availability of resources like nutrients, soil moisture and light paved way for higher leaf area per plant (leaf area index). These results are conformity with the findings of Kumara et al (2007) and El Naim and Jabereldar (2010).

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- Based on the results of this study, the weeding three times at 15, 30 and 45 days after sowing are effective to control weeds and recommended to improved yield of roselle crop in sandy dunes of north Kordofan (Sudan) under rain-fed conditions in traditional agricultural sector.

References

| [1] | Adjun, J. A. Effect of Intra row spacing and weed control on growth and yield of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.). Research and Development Center.University of Agriculture AbeokutaNigeria Agriculture and amp; Environment, 2003; 3: 91–98 |

| [2] | Alam,M. S.B. K., Biswars, M. A.,Gaffer and M. K. Hussain, 1995. Weed control in up land rice, Fffciency of weeding different stages of seeding emergence in direct Rice. Bangala J. Sci. Lnd Res. 30:155-167 |

| [3] | Anonymous, 1959. The wealth of India: Raw materials. Council of ci. & Indus. Res., 14: 13 – 12 |

| [4] | Aziz, E. E., N. Gad and N. M., Badran, 2007. Effect of Cobalt and Nickel on Plant Growth, Yield and Flavonoids Content of Hibiscus sabdariffa L Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 1: 73-78 |

| [5] | Baylan, R. S., Bhan, V. M. and Malik, R. K. The effect of weed removal at different times on the yield of cotton. Cotton Development. 1983; 13: (2) 9 – 10 |

| [6] | Cheweya, J., 1992. Agronomic Improvement of Indigenous Plant Germplasm in African Agriculture. A case study of Indigenous vegetables in Kenya, save guarding the Genetic Basis of Africans Traditional crops. Putter,a (Ed), Proc. CTA/IPGRI/UNEP Seminar, Nairobi, Kenya, pp: 105 – 113 |

| [7] | Chowdhury, M. A. H., Talukder, N. M., Chowdhury, A. k . and Hossain, M. Z. Yield and nutrient up take. Bangala.J.Sci. 1995; 22: 93 – 98 |

| [8] | El Naim, A. M., Eldoma, M. A. and Abdalla, A. E. 2010a. Effect of weeding frequencies and plant density on vegetative growth characteristic of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) in North Kordofan of Sudan. International Journal of Applied Biology and Pharmaceutical Technology, 1(3): 1188- 1193 |

| [9] | El Naim, A. M. and Ahmed, S. E. 2010. Effect of weeding frequencies on growth and yield of two roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffaL) Varieties under rain fed. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(9): 4250-4255 |

| [10] | El Naim A, M. and Jabereldar, A. A. 2010. Effect of Plant density and cultivar on growth and yield of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.Walp). Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(8): 3148-3153 |

| [11] | Gomez, K.A., Gomez, A. A.. Randomized complete block design analysis. In: Statistical procedures for the agriculture research. John Willy and Sons, New York. 1984 |

| [12] | Ibeawuchi, I. I. J., biefuna, C.O. and Ofoth, M.C. An evaluation of four varieties Inter cropped with Okra. Pakistan journal of Biological Science, 2005; 8 : 215 – 219 |

| [13] | Khater, M. R. and Ahmed, S.K. Effect of sowing dates and planting distance on vegetative growth, yield and active substances on Roselle plant –Agric. REs. Cent. Hort. Inst. Medicinal and Aromatic plant section. Dokki. 1992 |

| [14] | Kumara, O., T. Basavaraj and P. palaiah, 2007. Effect of weed management practices and fertility levels on growth and yield parameters in finger millet. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci, 20: 230-233 |

| [15] | Mahadevan, N., Shivali and K., Pradeep, 2009. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. An overview. Natural Product Radiance, 8 : 77- 83 |

| [16] | Mahmoud, A. M., M.O., Khidir, A. M., Khalifa, A.B., Elahmadi, H. A., Musnad, and I. E., Mohamed, 1996. Sudan country report to the FAO. International Technical conference on plant Genetic Resource, Khartoum. pp22 -23 |

| [17] | Mclean, K. Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.), or Karkadi as cultivated edible plants. Agricultural Science. Sudan. 170/ 543/,Project working paper, FAO, Rome. 1973 |

| [18] | Morton, F.J., 1987. Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L). Fruit of Warm Climates. Creative Resources Systems, Inc. Miami, Florida |

| [19] | Small, E. Culinary Herbs. National Research Council (N.R.C.), esearch press. 2006; PP. 395 – 396 |

| [20] | Sulaiman, A.A. Genetic and Interrelationships among Agronomic character in Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.). M.S.c.Thesis Faculty of Natural Resources and environmental studies, University of Kordofan .Sudan. 2005 |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML