-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Plant Research

p-ISSN: 2163-2596 e-ISSN: 2163-260X

2012; 2(1): 59-63

doi:10.5923/j.plant.20120201.09

Myrmecofauna Fruit Trees Infected by Loranthaceae Orchards Lokomo (East Cameroon)

Dibong SD.1, 2, 3, Mony R.4, Azo'o JRN.1, Din N.1, Boussim IJ.5, Amougou A.6

1Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P. O. Box 24157, Cameroon

2Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences,

3University of Douala, P. O. Box 2701, Cameroon

46Department of Physiology and Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Yaoundé I, P. O. Box 812, Cameroon

5Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P. O. Box 24157, Cameroon

6Department of Physiology and Plant Biology, UFR in Sciences of Life and Earth,

Correspondence to: Dibong SD., Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P. O. Box 24157, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this study was to identify the myrmecofauna fruit trees infected by Loranthaceae orchards Lokomo (East Cameroon). The collection and identification of myrmecofauna was made on an area of 5 ha. The work was conducted from October to December 2010. The orchards consist of a mixture of exotic ornemental trees, fruit trees for consumption and forest species deliberately left in place. Woody species hosts concerned were Albizia adianthifolia, Calliandra susinamensis, Citrus maxima, Entandrophragma cylindricum, Psidium guajava, Macaranga hurifolia, Phyllanthus discoides and Terminalia mantaly. A total of seven ant species grouped in six genera and two subfamilies (Formicinae and Myrmicinae) were identified. In Formicinae, two genera have been identified, Camponotus and Oecophylla. Myrmicinae in turn had three genera, Atopomyrmex, Crematogaster and Tetramorium. The activity of myrmecophilous revealed that ants forage on flowers, fruits and suckers of T. ogowensis and T. preussii. The suckers dried out and degenerated causing the death of the tufts.

Keywords: Myrmecofauna, activity, Loranthaceae , death, Lokomo, Cameroon

Cite this paper: Dibong SD., Mony R., Azo'o JRN., Din N., Boussim IJ., Amougou A., Myrmecofauna Fruit Trees Infected by Loranthaceae Orchards Lokomo (East Cameroon), International Journal of Plant Research, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 59-63. doi: 10.5923/j.plant.20120201.09.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The permanent forest of Cameroon has 14 million ha of forest, including 8 million hectares of production forest and 6 million ha of forest and wildlife reserves[16]. Forest ecosystems are home to 80 % of the carbon of terrestrial vegetation and 40 % of soil carbon. The role of carbon sinks in tropical forests is essential to absorb much of the atmospheric CO2.Parts of the forests of Cameroon are located in biogeographic areas experiencing a high degree of endemism. These are the forests of the mountains of Cameroon and Nigeria's forests and plains of western Cameroon and Gabon [19]. The equatorial forests of southeastern region of Cameroon and much more: the "Congo Basin" where some 20 % of the tropical forest is still intact. The Congo basin is the second largest forest in the world in terms of area after the Amazon rainforest. The Congo Basin is known for its exceptional biological and cultural diversity[20]. But over the last twenty years, the exploitation of tropical forests has reached a level so alarming that the sustainability of this resource is in question. One consequence of logging is the creation of canopy gaps resulting in the proliferation of parasitic Loranthaceae[15].The Loranthaceae are flowering, chlorophyll and hemiparasitic epiphytes which are located on the aerial parts of their hosts, and are responsible for economic damage, ecological, technological and morphogenetic varied crops or woody species parasitized[18].In temperate regions, this plant family comprises of 950 species belonging to 17 genera. In Africa and Arabia, Polhill and Wiens[17], over 500 species has been identified. In Cameroon, Balle[2] listed 7 genera comprising about 26 species. These parasitized species, which have not been sufficiently studied by research structures, is now a real constraint for extension, home gardens, orchards and spontaneous species in Cameroon[4]. The main objective of this study is to contribute to the knowledge of the host species myrmecofauna parasitized by Loranthaceae Lokomo orchards in eastern Cameroon. The specific objectives are: (1) Inventary Loranthaceae found in orchards Lokomo, (2) identify the associate myrmecofauna and (3) monitor their feeding activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

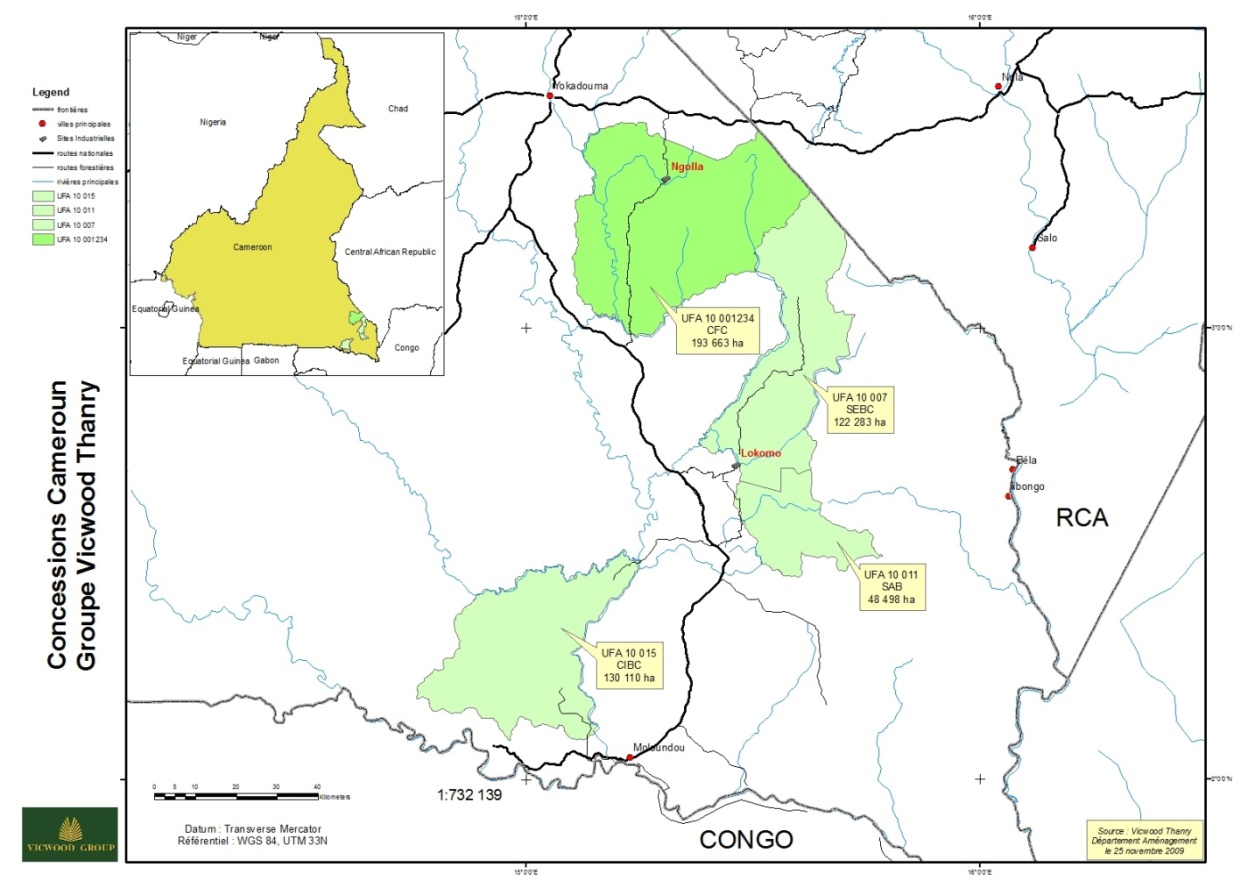

- Lokomo (latitude, 2° 40 'and 3° 09' N, longitude 15° 20 'and 15° 46' E, altitude ranging between 300 and 500 m) is the forest management unit No. 10-007, located in the Eastern region, department of Boumba and Ngoko, straddling the boroughs and Yokadouma Moloundou. It has a total surface area of 122.294 ha (Fig. 1). The climate is continental influenced by two equatorial winds; the monsoon and the harmattan. These two winds meet to give the intertropical front which regulates the seasonal rythm. Climatological data provided by the Group Vicwood Thanry dating twenty years (1991-2011) distinguished four seasons (two rainy seasons and two dry seasons), which are divided as follows: mid-March to late June is the early rainy season, late June to mid-August is the short dry season, mid-August to mid-November is the rainy season and mid-November to mid-March is the long dry season. The region is characterized by high rainfall (1580.99 mm), average temperatures of about 25.19℃ and the relative humidity is high throughout the year.

2.2. Data Collection for the Study

2.2.1. Site Selection Study

- The site chosen for this study is twenty-five years old occuping about 5 ha and contains orchards and secondary forests degraded. Four surveys were conducted in three orchards (orchards 1, 2 and 3) and in a degraded secondary forest following a transect oriented from homes into the forest.

| Figure 1. Lokomo site location on the map of Cameroon |

2.2.2. Course Site

- For observations, the surveys’ roaming method was used. It was to browse the site chosen along the slopes, explore the trees or shrubs grown spontaneous which were likely to be infected by Loranthaceae in different plant communities.The collection and identification of myrmecofauna were conducted from October to December 2010. Agroecosystems consist of a mixture of ornamental trees, exotic fruit for consumption and forest species deliberately left in place. Ants working on the host species were harvested using a machete, which left behind raising points of inking. The ants were collected and stored in black boxes containing alcohol at 70℃ in the Animal Biology laboratory of the Faculty of Science of the University of Douala.Identification of the ant species was done using identification keys from the database of African ants (www.antbase. org) and nomenclature approved by specialists of African ants.

2.3. Data Processing

- Excel software was used for Data processing as well as for statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Parasitism by orchards Lokomo Loranthaceae

- A total of 17 host species of Loranthaceae were identified. These species were grouped into 10 families and Rutaceae is the most diversified with five species (Table 1).Counts of the number of clumps of Loranthaceae identified during the study revealed that Tapinanthus preussii was the most wide spread in the study site with a percentage of parasitism of 64.49 %, followed by Tapinanthus ogowensis with 35.44 % and lastly Phragmanthera capitata with a single clump representing just 0.06 %.

3.2. Inventory Myrmecofauna

- A total of seven ant species grouped in six genera and two subfamilies were identified (Table 2), Formicinae and Myrmicinae. In Formicinae two genera were identified Camponotus and Oecophylla. Myrmicinae in turn had three genera, Atopomyrmex, Crematogaster and Tetramorium.In Camponotus, three species of ants were identified Camponotus acrapimensis, C. vividus and Camponotus sp. Oecophylla, Atopomyrmex, Crematogaster and Tetramorium each had one species that were respectively Oecophylla longinoda, Atopomyrmex mocqueresy, Crematogaster sp. and Tetramorium aculeatum.It is clear from the above table that the ant species Camponotus acrapimensis, Camponotus vividus and Crematogaster sp. live on several host species parasitized by the Loranthaceae. Oecophylla longinoda colonizes two host species. Tetramorium aculeatum and Atopomyrmex mocqueresy (Table 2).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3.3. Interaction between Host/Ant and Loranthaceae Lokomo

- The myrmecophilous activity revealed that ants forage on flowers, fruits and suckers of T. ogowensis (Fig. 2) than on T. preussii (Fig. 3). A freehand cut with a machete showed that these ants dug many galleries where their presence was remarkable and significantly abundant. In all Tapinanthus identified, the tunnels in the wood suckers host eventually rot.

| Figure 2. Sucker rotten Tapinanthus ogowensis |

| Figure 3. Sucker rotten Tapinanthus preussii |

| Figure 4. Gallery dug in the heart of the wood of the host by ants (yellow arrow) |

4. Discussion

- Three species of Loranthaceae have been recorded in the Lokomo site. This is Tapinanthus ogowensis (Engler) Danser, Tapinanthus preussii (Engler) and Van Tieghem Phragmanthera capitata (Sprengel) S. Balle. These parasites are not specific to Lokomo which belongs to the Guinea- Congolian, semi-deciduous rain forest area. Other areas in Africa have also been reported to have these parasites. These areas include Benin, Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Niger and Senegal[5,6] al., 2009, 2010c).It appears that the ant species Camponotus acrapimensis, C. Vividus and Crematogaster sp. live on multiple hosts parasitized by the Loranthaceae. It should be noted that these are the dominant ants. Mony et al.[12,13] noticed that Crematogaster ants were the most abundant at 90.19 % in orchards and gardens of the Logbessou boxes.Crematogaster ants of are often dominant in their communities. In New Guinea, a species living in the canopy (Crematogaster major), represents 56-99 % of the ants collected on trees[10]. Crematogaster irritabile can occupy, in turn, over 99 % of the trees on one quadrant of a hectare in New Guinea[11]. Crematogaster parabiotica overwhelmingly dominates the Peruvian Amazon.The plants myrmecophilous are mostly associated with one or a few species of specialized ants and the association is mandatory for the survival of the partners[21,1,14,7,9]. The loyalty of these interactions is favored by the housing and/or food provided by plants. In return the ants protect their host against defoliators and competitors and can even supply them with nutrients. On the side of the plants, the production of housing for ants (domatia) is a fundamental nature of myrmecophilous species. These domatia are hollow structures that can be localized on the trunk, petiole, stipules or leaf blade. In addition, the settlement of certain myrmecophytes requires drilling of the entry of domatia on the part of the ants[3,8].Observations on the activity in the myrmecophilous site Lokomo showed that ants foraging on flowers, fruits and suckers of both T. ogowensis and T. preussii. A freehand cut with a machete shows that these ants dig many galleries where their presence is remarkable and significantly abundant. In all Tapinanthus identified, the tunnels in the wood suckers host eventually rot. The sucker serves as fodder for ants. Ants by burrowing in search for sweet substances will feed inside the suckers, causing desiccation and hence will leave a door in the heart of the wood of the host and the decay will continue.

5. Conclusions

- The study performed in the industrial site of the Group Vicwood Thancy of Lokomo in the departments of Boumba and Ngoko (Eastern Region) revealed that there are 3 species of Loranthaceae: Tapinanthus preussii (Engler) Van Tieghem, Tapinanthus ogowensis (Engler) Danser and Phragmanthera capitata (Sprengel) S. Balle. The records of the couple myrmecofauna associated with host/ Loranthaceae showed seven ant species grouped in six genera and two subfamilies. They are: Camponotus acrapimensis, C. vividus, Camponotus sp., Oecophylla longinoda, Atopomyrmex mocqueresy, Crematogaster sp. and Tetramorium aculeaum. The two subfamilies are Formicinae and Myrmicinae. Interactions between host/Loranthaceae/ant showed that these ants created galleries in the haustorium of Loranthaceae. These galleries interrupt the collection of sap from their hosts of Loranthaceae and precipitated death.

References

| [1] | Alonso, L.E. (1998) Spatial and temporal variation in the ant occupants of a facultative ant-plant. Biotropica 30, 201-213. |

| [2] | Balle, S. 1982. Flore du Cameroun, 23. Loranthaceae, (Eds. B. Satabié et J. F. Leroy) D.G.R.S.T., Yaoundé, 82 p. |

| [3] | Brouat, C., Garcia, N., Andary, C. and Mc Key, D. (2001) Plant lock and ant key: pairwise coevolution of an exclusion filter in an ant-plant mutualism. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 268, 2131-2141. |

| [4] | Dibong, S.D., Din Ndongo., Priso, R.J., Taffouo, V.D., Fankem, H., Salle, G. and Amougou Akoa (2008) Parasitism of host trees by the Loranthaceae in the region of Douala Cameroon). African journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2 (11), 371-378. |

| [5] | Dibong, S.D., Engone, O.N.L., Din Ndongo., Priso, R.J., Taffouo, V.D., Fankem, H., Salle, G. and Amougou Akoa (2009) Artificial infestations of Tapinanthus ogowensis (Engler) Danser (Loranthaceae) on three host species in the Logbessou Plateau (Douala, Cameroun). African journal of Biotechnology 8 (6), 1044-1051. |

| [6] | Dibong, S.D., Ndiang, Z., Mony, R., Boussim, I.J. and Amougou Akoa (2010) A parasitic study of Phragmanthera capitata (Sprengel) S. Balle (Loranthaceae) in the anthropic environments: The case of the Ndogbong chieftain’s compound orchard (Douala, Cameroon). African journal of Agricultural Reseach 5 (15), 2051-2055. |

| [7] | Djiéto-Lordon, C., Dejean, A., Gibernau, M., Hossaert-Mc Key, M. and Mc Key, D. (2004) Symbiotic mutualism with a community of opportunistic ants: protection, competition, and ant occupancy of the myrmecophyte Barteria nigritana (Passifloraceae). Acta Oecologica 26, 109-116. |

| [8] | Federle, W., Fiala, B., Zizka, G. and Maschwitz, U. (2001) Incident daylight as orientation cue for holeboring ants: prostomata in Macaranga ant-plants. Insectes Sociaux 48, 165-177. |

| [9] | Gaume, L., Zacharias, M. and Borges, R.M. (2005) Ant–plant conflicts and a novel case of castration parasitism in a myrmecophyte. Evolutionary Ecology Research 7, 435-452. |

| [10] | Leponce M. and Missa O. (1998) Structure of an ant assemblage in the canopy of a tropical rainforest in Papua New Guinea. In: Social insects at the turn of the millennium. Proceedings of the XIII international congress of IUSSI (Schwarz M.P. & Hogendoorn K.), pp. 319. |

| [11] | Leponce M., Roisin Y. and Pasteels J.M. (1999) Community interactions between ants and arboreal-nesting termites in New Guinea coconut plantations. Insectes sociaux 46, 126-130. |

| [12] | Mony R., Dibong S.D., Ondoua J.M. and Bilong Bilong C.F. (2011) Study of Host-Parasite Relationship among Loranthaceae Flowering Shrubs-Myrmecophytic Fruit Trees-Ants in Logbessou District, Cameroon. Annual Review & Research in Biology 1 (3), 68-78. |

| [13] | Mony R., Ondoua J.M., Dibong S.D., Boussim I.J. and Amougou A. (2010) Myrmécofaune arboricole associée aux couples Phragmanthera capitata (Sprengel) S. Balle/ hôtes au verger de la chefferie de Ndogbong (Douala, Cameroun). International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 3 (6), 1346-1356. |

| [14] | Murase, K., Itioka, T., Inui, Y. and Itino, T., 2002. Species specificity in settling-plant selection by foundress ant queens in Macaranga-Crematogaster myrmecophytism in a Bornean dipterocarp forest. Journal of Ethology 20, 19-24 |

| [15] | Norton, D.A., Hobbs, R.J. and Atkins, L. (1995) Fragmentation, disturbance, and plant distribution: mistletoes in woodland remnants in the western Australian wheat belt. Biological Conservation 9, 426-438. |

| [16] | PSFE. (2003) Composante 2 "Aménagement des Forêts de Production du Domaine permanent et valorisation des produits forestiers", 138 p. |

| [17] | Polhill, R. and Wiens, D. W. 1998. Mistletoes of Africa. Kew Ed. ISBN, 370 p. |

| [18] | Sallé, G., Tuquet, C. et Raynal-Roques, A. 1998. Biologie des phanérogames parasites. C. R. Soc. Biol. 192, 36. |

| [19] | Stattersfield, A..J., Crosby, M.J., Long, A.J. and Wege, D.C. (1998) Endemic Bird Areas of the World. Priorities for biodiversity conservation. BirdLife Conservation Series 7. Cambridge: Bird Life International, 846 p. |

| [20] | Verbelen, F. (1998). L’exploitation abusive des forêts équatoriales du Cameroun, 49 p. |

| [21] | Yu, D.W. and Davidson, D.W. (1997) Experimental studies of species-specificity in Cecropia-ant relationships. Ecological Monographs 67, 273-294. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML