-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2025; 15(2): 46-56

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20251502.02

Received: Jul. 3, 2025; Accepted: Jul. 26, 2025; Published: Jul. 29, 2025

Factors Influencing Waiting Time to First Conception in Women with Different BMI: Insights from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2022 Data

Jahanara Akter Keya

Department of Statistics, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Jahanara Akter Keya, Department of Statistics, University of Chittagong, Chattogram, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Maternal nutrition is a prerequisite for safe conception, safe motherhood, and a healthy nation. This study aims to investigate the differences in the waiting time to first conception among different categories of nutritional status of ever-married women in Bangladesh. A total of 8374 women aged 15-49 were sampled from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2022. The mean waiting time to first conception of a woman is found to be 23.21±25.09 months without censored cases. Women who are overweight take a relatively longer time to conceive than other women. The results from Kaplan-Meier analysis, Log Rank test, and Cox Proportional Hazard model indicate that geographical region, respondent's education, partner’s education, decision maker for using contraception, age at first marriage, spousal age difference, and marital duration are significant determinants of the timing of first conception. The results of this study confirm that body mass index (BMI) is the most salient factor in determining the timing of first conception and that women with a healthy BMI have a faster transition to conception than those who are underweight or overweight.

Keywords: Conception wait, Body mass index, Kaplan-Meier Survival analysis, Cox proportional hazard model

Cite this paper: Jahanara Akter Keya, Factors Influencing Waiting Time to First Conception in Women with Different BMI: Insights from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2022 Data, Public Health Research, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 46-56. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20251502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- An improved health status of a woman during her reproductive years confirms an enhanced health status of the country. The advancement of maternal physical and mental health is necessary to improve child health along with to alleviate the national health burden [1]. Bangladesh, a developing and densely populated country, faces a significant nutritional challenge. There are many underweight women in rural areas and urban slums of Bangladesh [25,12]. However, the prevalence of underweight is decreasing day by day, while the prevalence of overweight is an alarming condition that confirms the double burden of malnutrition during women's reproductive years [15,17]. A similar scenario can be observed in most developing countries. Specifically, overweight and obesity are more prevalent than underweight in women [19].A study demonstrated, the first birth interval can provide an indication of nutritional status. There is a relationship between women's body mass index (BMI) and their fertility, with both underweight and overweight/obese women facing greater challenges in conceiving [20]. Another research found that being underweight or overweight can have a negative impact on fertility [31]. In fact, women who are underweight or overweight take longer to get pregnant [5,6,9,32]. Previous study has explored that obesity is the key reason for sub-fecundity [22]. Maternal obesity has been associated with a delayed time to conception, an increased risk of gestational diabetes, an increased likelihood of caesarean section, and an increased risk of stillbirth [30].Conception is a sign of becoming a mother and the time to pregnancy is linked to women's fertility patterns. The timing of first conception is a valuable indicator for understanding and measuring women's fertility behavior. In Bangladeshi society, women usually want to have a child as soon as they get married. Despite this, the mean waiting time to conception in Bangladesh is around 19 months, which is longer than in other low-fertility populations [13]. Since child marriage is a prevalent social phenomenon in Bangladesh, most married women are not physically mature enough to become pregnant shortly after marriage [24]. Consequently, a negative correlation is observed between age at first conception and age at first marriage [2].There are numerous studies in the literature on waiting time to conception and related issues, of which only a few were conducted in Bangladesh [2,13] and most in other countries [27,7,23,14]. Waiting time to conception is influenced by a variety of factors, including place of residence, region of residence, education, age at first marriage, exposure to mass media and BMI [13,29]. In addition, the socioeconomic status and occupation of respondents and their partners influence the timing of first motherhood [3]. Contraceptive use and menstrual cycle length are also significantly associated with the time to pregnancy [4,28]. Based on a comprehensive literature review, we can claim that few studies have examined the effects of covariates on waiting time to conception among women with different BMIs, and no such study exists for Bangladesh. However, if we can find out to what extent the waiting time for conception varies among women categorized by BMI, proper initiatives such as treatment and counselling can be taken to prevent delayed pregnancy. The objective of this study is to examine the timing of first conception in underweight and overweight/obese women and the factors influencing it in the context of Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

- Source of DataThe study uses a secondary data source, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS), 2022. This survey is a part of the worldwide Demographic and Health Survey. The 2022 BDHS was conducted under the authority of the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The 2022 BDHS is a countrywide survey with a nationally representative sample of approximately 30,078 ever-married women aged 15-49, to evaluate health and demographic indicators, mainly maternal and child well-being, fertility, family planning, and nutritional status at the national and divisional levels. All participants of the study were provide an informed consent before conducting the survey. One third of the selected households were considered for anthropometric measurement in BDHS 2022.To carry out the research, we investigated 8374 married women between the ages of 15 and 49. Currently, pregnant women are excluded to represent their nutritional status, and women who had ever had a terminated pregnancy are also omitted to better represent the first conception wait.Formation of the variable “Timing of First Conception”To determine the "Timing of First Conception" for Bangladeshi women, 8374 respondents from 30,078 were chosen. To generate the variable, the whole dataset is first subdivided into two files: birth and no birth, which comprise 7617 and 757 respondents, respectively. The time to first conception is then calculated from both files and pooled to create a status variable with values of 0 for no birth happened and 1 for at least one birth.From the birth file, the first conception wait is calculated by using the following formulaConception Wait (Closed interval) = Date of first birth (CMC) – 9(Gestation period in months) – Date of first marriage (CMC)From no birth file, the first conception wait is calculated by using two formulae considering closed interval and exposure interval (regarded as censored cases).Date of first conception = CMC pregnancy ended – Month pregnancy endedConception Wait (Closed interval) = Date of first conception – Date of first marriageExposure Interval (Open Interval) = Date of Interview (CMC) – Date of first marriageFactors Influencing Time to first ConceptionTo assess the influential characteristics of women's first conception waits with different categories of nutritional status several cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic variables have been considered. Living environment, geographical region, and religion are considered cultural variables. To measure the socio-economic effect the study included some important variables like respondent education (illiterate, primary, secondary, and higher), respondent currently working, husband's education, husband’s occupation (Agriculture, Business, service, and others), access to mass media, socio-economic status, decision making autonomy, and decision maker for using contraception. Three variables are used to measure decision-making autonomy: The person who usually decides on: the respondent's health care, the Person who usually decides on: large household purchases, and the Person who usually decides on: visiting family or relatives. The decision making autonomy is formed and coded as 0= “no decision taken”, 1= “one decision taken”, 2 = “two decision taken” and 3= “three decision taken” [26]. Age at first marriage, spousal age difference and marital duration are considered for demographic variable.Statistical analysisIn this analysis, descriptive statistics were employed to detect the mean difference in first conception wait among different categories of BMI. Normally, survival data are not fully observed but rather censored. Some individuals are still alive at the end of the study or analysis so the event of interest has not occurred. Therefore, right censored data are present. The Kaplan-Meier method [16], also known as the “product limit method”, is a non-parametric method used to estimate the probability of survival past given time points (i.e., it calculates a survival distribution). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Log-Rank test are applied to present the survival curves and to test significant difference in survival curves among different independent variable groups [10,18]. To estimate the significant factors that influence the timing of first conception Cox-proportional hazard analysis is used [8]. This method is applied to identify the risk or prognostic factors relative to baseline hazard function. The analysis is carried out using SPSS 26.0.

3. Results

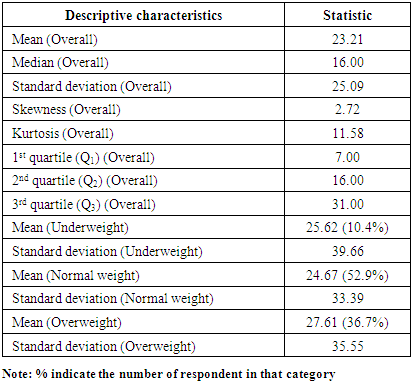

- In this study, we attempt to find the differentials of the timing of first conception for different nutritional status categories. Table 1 shows that the overall mean of first conception wait is 23.21 months with a standard deviation of 25.09 months who has at least one live birth. The distribution of the first conception wait is positively skewed and highly leptokurtic, as directed by the skewness and kurtosis values of 2.72 and 11.58, respectively. About 50% of women take 16 months for first conception while 25% women conceive after 31 months. Considering all the respondents, the average time to conception is found highest among underweight and overweight women, 25.62 months and 27.61 months respectively that the normal weight women (24.67 months).

|

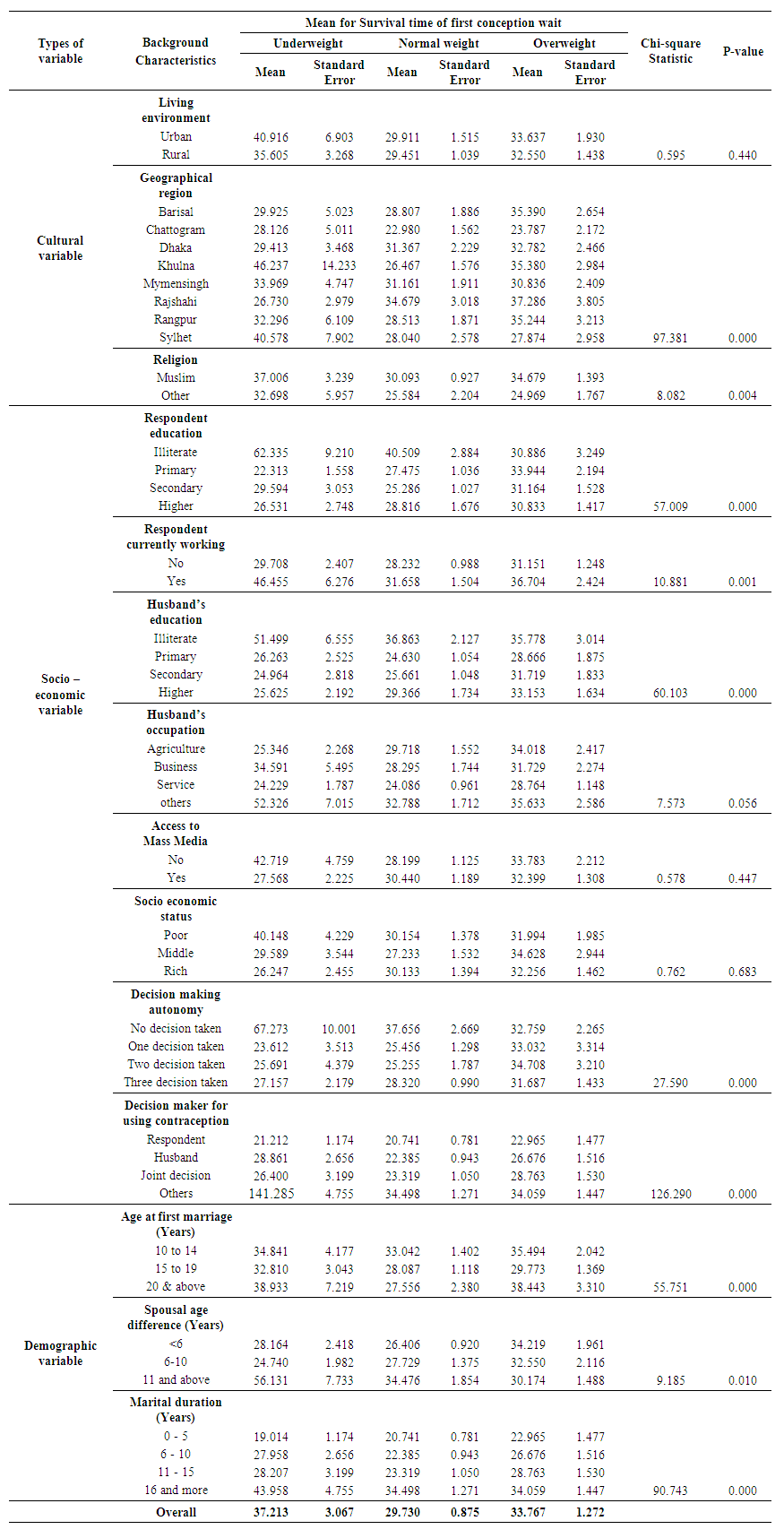

| Table 2. Mean for survival time of first conception wait by some selected background characteristics into different categories of BMI and log rank test statistics for equality of survivor functions |

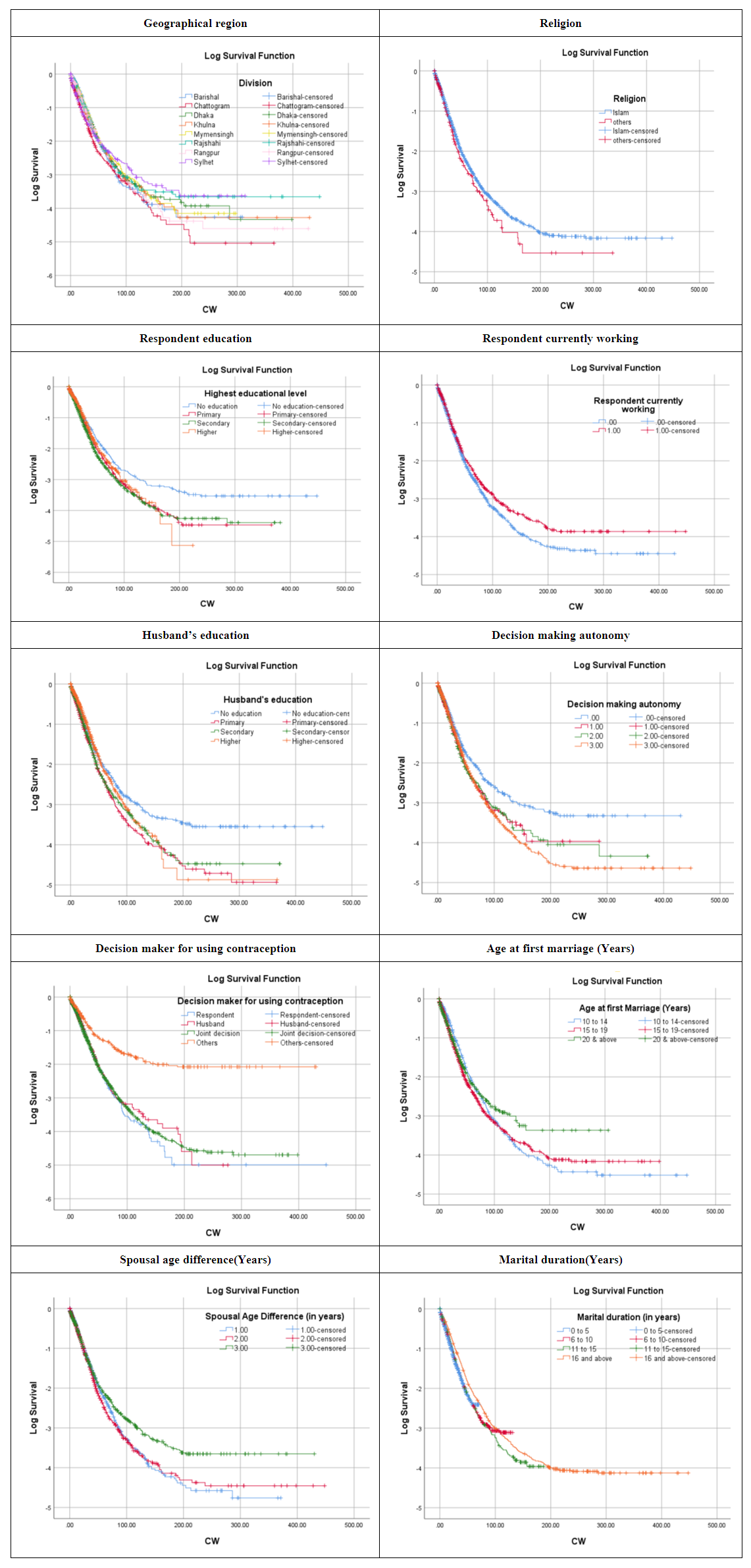

| Figure 1. Survival curves of the first conception wait with different background characteristics |

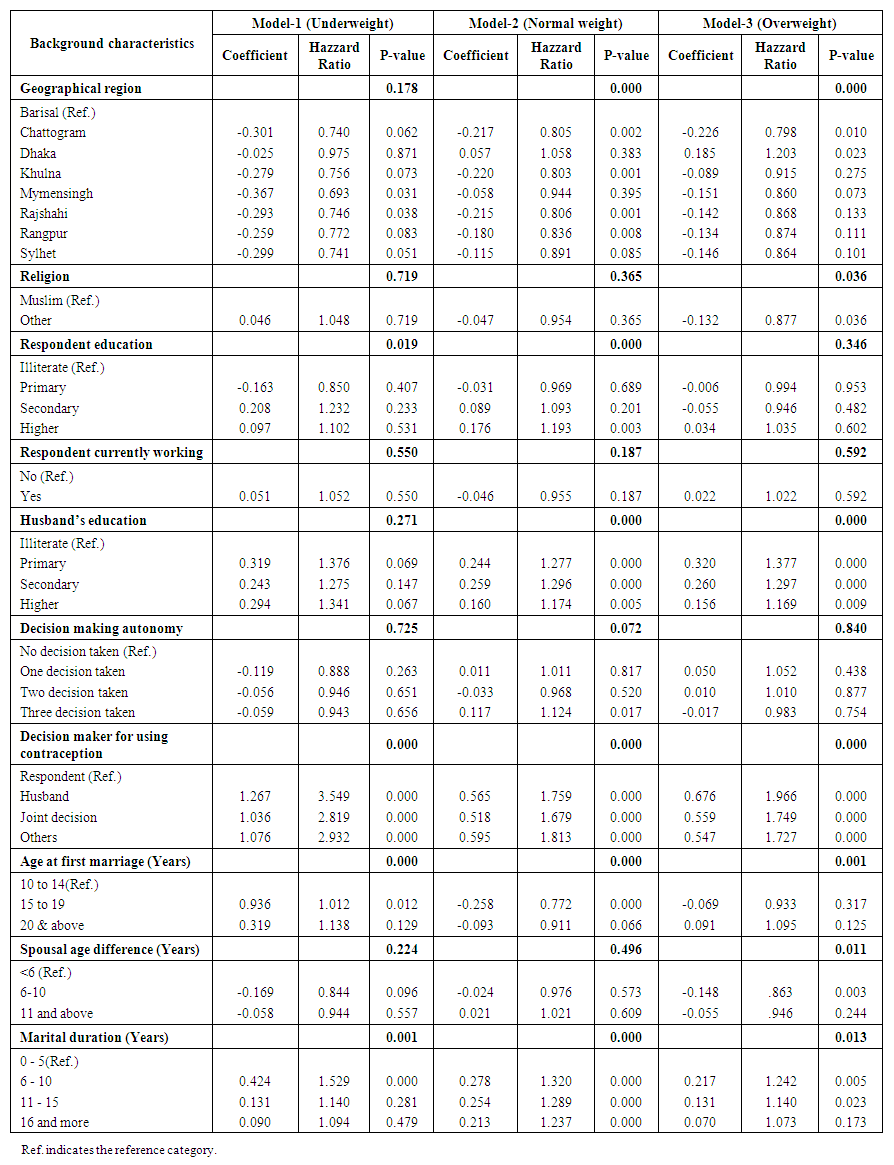

| Table 3. Cox proportional Hazard model estimates of the effects of selected background characteristics on first conception wait into different categories of BMI of women in Bangladesh, 2022 |

4. Discussion

- The strength of this study is that it analyzed a nationally representative and reliable data set and studied the extremes of BMI simultaneously and its influence on time to first pregnancy among ever-married non-pregnant women in Bangladesh using various sophisticated statistical techniques.In this study, we report the time to first pregnancy can be used as a measure of women's nutritional status by testing whether overweight and underweight women take a longer time to conceive than healthy women. There is a significant effect of nutritional status on the time to first conception among ever-married women in Bangladesh is a topic of concern with wide-ranging consequences for reproductive health status. This research suggested inadequate nutritional status is one of the dominant factors for a prolonged time to first conception. Though underweight is decreasing but the prevalence of overweight is increasing at an alarming rate. The findings of the research also suggest that malnourished (overweight and underweight) women take more time for their first conception than healthy women. This results agree with some previous research that have shown increases infertility among overweight women [5,31]. Obesity in women can affect regular hormonal cycles, affecting irregular ovulation and menstrual periods, which can make conception more challenging. The timing of the first conception varies in different geographical regions as the privilege of education, medical treatment, and working opportunities are not uniform among different geographical regions. Another study also confirm that the fertility pattern varies with different locations [11]. The present study hints that a significant effect has been found on time to first pregnancy with respondent's schooling. Higher levels of educational status have been linked with a tendency to start the family earlier. Educated women are more likely to wait for a better career, economic solvency, and a desire to afford a better future for their children. So that they start their marital life with older age and try to conceive earlier. Similar results showed that women with secondary and higher education are more likely to conceive earlier than the women who have primary education [21]. The use of contraception is a dominant factor for affecting fertility pattern of the women. This study confirms that the decision maker for using contraception plays a significant effect on timing of first conception. Women who can take decision about the use of contraception are less likely to conceive than the women who did not take the decision by themselves. A study estimated that there is a negative effect on fertility pattern with decision making autonomy in household which are related with the use of contraception behavior [26].Age at first marriage is one of the most important factors for determining the timing of first conception in our country. It is found a significant contributor among all the three levels of BMI. Moreover, the findings from this study showed that women from the overweight group with higher spousal age differences had a higher risk of conceiving earlier than the lower spousal age differences. Since spousal age gap indicates that women have less freedom to make decisions about her fertility behavior. Marital duration is also positively associated with the mean conception wait. Overall, this results display the timing of first conception depend on the BMI level. As overweight and underweight women have to wait more than the normal weight women. So, it is essential to raise awareness in order to reduce the rate of both underweight and overweight, which are responsible for prolonged conception wait.

5. Conclusions

- Bangladesh has made significant progress in health over the past decade. Maternal health provides a good understanding of the key elements needed to reduce maternal mortality, caesarean sections and the ability to deliver a healthy baby. In essence, women's health is an important indicator of the quality of access and effectiveness of the country's health sector. Bangladesh faces both the problem of underweight and overweight among women, which is alarming and considered a double burden. The findings of this study clearly demonstrated that healthy women have faster transition to conceive than the underweight and overweight women. Due to malnourishment, the first conception wait is very longer in our country. The time of first conception is relatively higher in overweight women than in underweight and normal-weight women. The results of the Cox proportional hazard model show that region, respondent education, husband education, decision maker for using contraception, age at first marriage, spousal age difference, and marital duration are influential factors in the timing of first conception among different categories of BMI. Hence, nutritional status should be improved by addressing various factors to reduce the timing of first conception and have a healthy baby. Different campaigns should be organized at the school level to raise awareness about the importance of maternal health status.

Limitation

- Longitudinal survey data should be used in future research to determine the effect of nutritional status on the waiting time to first conception from date of the first marriage, considering the information of the menstrual cycle and coital frequency.

Ethics Approval

- The authors used a secondary data which is available in the website http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm. After registration one can easily get access to use the data freely from the website. The Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) data was permitted by both the Bangladeshi Ethics Committee and the Ethics Committee of the ICF Macro in Calverton, New York, USA.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML