-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2025; 15(2): 35-45

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20251502.01

Received: May 19, 2025; Accepted: Jun. 16, 2025; Published: Jul. 3, 2025

Hazards on the Frontlines: Occupational Health and Safety Risks Faced by Ghana’s Environmental Health Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Isaac Monney1, Harrison Yengbe2, Dennis Dekugmen Yar2, Kofi Sekyere Boateng2, Emmanuel Darteh3

1Department of Environmental Health and Sanitation Education, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Mampong-Ashanti, Ghana

2Department of Public Health Education, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Mampong-Ashanti, Ghana

3Department of Science Education, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Mampong-Ashanti, Ghana

Correspondence to: Isaac Monney, Department of Environmental Health and Sanitation Education, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Mampong-Ashanti, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

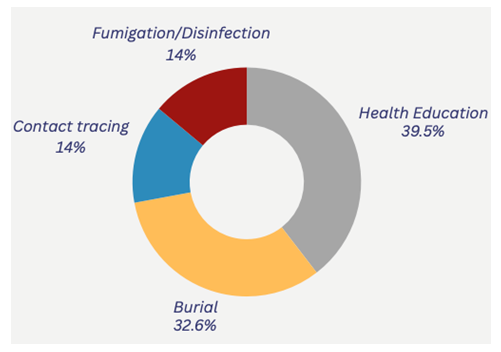

Environmental Health Professionals (EHPs) in Ghana played a central role in the national response to COVID-19. Yet their welfare and safety received little attention. This study examines the occupational hazards and safety risks faced by EHPs in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic and the training, resources, and support provided to mitigate these risks. Data were collected from 13 Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Assemblies spanning six regions, with the highest COVID-19 case counts. A total of 215 EHPs were selected for the study through proportional stratified sampling, complemented by 13 key informant interviews and 2 focus group discussions to explore their lived experiences and the institutional support they received. Quantitative data was analysed with SPSS (version 25) while NVIVO was employed to analyse qualitative data. Findings revealed that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, 40% led community health education, 33% managed burials, 14% performed contact tracing, and 14% carried out fumigation. Eighty per cent reported work-related physical injuries, particularly during burials. One-third (33%) suffered adverse chemical exposures, and a similar proportion (32%) endured psychological distress. Only 1% contracted COVID-19, and just over half (58%) received at least one COVID-19 training session. PPE shortages were widespread – one-third (34%) lacked reliable access, and two-thirds (66%) resorted to personal purchases, particularly among young officers (χ2=18.69; p=0.002). Despite the psychological distress, EHPs had no access to mental health services, lacked health insurance coverage for COVID-19, and did not benefit from hazard allowances. To safeguard EHP welfare and maintain resilient public health responses, Ghana must institute enforceable OHS policies, ensure regular training, secure PPE supplies, extend health insurance and hazard pay, and provide dedicated mental health support for this indispensable workforce.

Keywords: Occupational health, Safety risks, Environmental health professionals, COVID-19 pandemic, Personal protective equipment, Workplace hazards, Ghana

Cite this paper: Isaac Monney, Harrison Yengbe, Dennis Dekugmen Yar, Kofi Sekyere Boateng, Emmanuel Darteh, Hazards on the Frontlines: Occupational Health and Safety Risks Faced by Ghana’s Environmental Health Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Public Health Research, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 35-45. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20251502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Occupational health and safety (OHS) is fundamental to public health. Yet work-related injuries and illnesses remain a global burden. Estimates by the ILO show that nearly 3 million workers died in 2019, representing a 26% increase in work-related mortalities from 2014 [1]. About 90% of these deaths were caused by work-related diseases, while a tenth was due to occupational injuries [1]. Besides fatalities, hundreds of millions suffer non-fatal injuries annually, showcasing the need for strong workplace health protections. Thus, hazardous exposures at work, whether physical, chemical, biological, ergonomic, or psychosocial, can result in significant morbidity and mortality. In low- and middle-income countries like Ghana, OHS challenges are compounded by limited resources and weak enforcement of safety regulations. In fact, Ghana lacks a comprehensive national OHS law for the general workforce, and many workers operate with little to no legal protection or formal safety nets [2,3].The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 exacerbated existing workplace hazards and introduced new ones for frontline workers. Globally, health and sanitation workers suddenly faced additional risks associated with the novel coronavirus. These included the apparent threat of infection, as well as indirect hazards from new work practices – for example, extended use of personal protective equipment (PPE) leading to heat stress and skin injuries, heightened fatigue, psychological trauma, stigma, and discrimination [4,5]. The International Labour Organisation and the World Health Organisation noted that measures to mitigate COVID-19 have created unconventional occupational risks. Prolonged wearing of masks, respirators, and gloves has been linked to dermatitis and other skin conditions, while workforce redeployment and overwork have worsened mental health strains [6,7]. Thus, the pandemic accentuated the importance of strengthening OHS systems, especially for those on the front lines of public and environmental health.Environmental Health Professionals (EHPs) represent a cadre of public health workers whose role became especially critical during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Ghana, EHPs (also referred to as sanitation officers) are responsible for enforcing sanitation regulations, managing waste and hygiene in communities, and mitigating environmental health risks under normal circumstances [8]. During the pandemic, their duties expanded to include contact tracing of infected persons, risk communication and health education in communities, disinfection of public places, and the dignified but safe burial of COVID-19 victims. These activities placed EHPs at the heart of the national COVID-19 response. However, such responsibilities also exposed them to significant occupational hazards. For instance, tracing contacts and educating the public brought some EHPs into close interaction with potentially infected individuals and occasionally hostile community members, posing risks of assault or infection. Undertaking mass disinfections exposed EHPs to chemical agents, such as chlorine, with the potential for respiratory irritation or other health effects. Particularly, supervising the burial of individuals who succumbed to COVID-19 required handling infectious human remains and heavy lifting, leading to concerns about both infection and physical injuries. Despite these risks, anecdotal reports suggested that EHPs in Ghana were not accorded the same level of support or recognition as other frontline health workers, such as doctors and nurses, during the pandemic [9]. Early in the pandemic, the Ghanaian government implemented incentive packages for healthcare workers nationwide. For example, the government provided tax waivers and a 50% salary bonus for frontline health personnel in public facilities [10,11]. Yet, these benefits did not include EHPs, who are administratively under local government structures rather than the Ministry of Health. Indeed, EHPs felt neglected and perceived that their contributions were undervalued [12]. This situation mirrors global observations. In the United Kingdom, environmental health practitioners stepped up to fill critical public health roles, such as contact tracing, during the COVID-19 pandemic, often working behind the scenes [13]. The pandemic revealed that occupational health risks among “essential” but less visible worker groups, such as sanitation and environmental health personnel, have been under-researched and insufficiently addressed.In light of this, it is crucial to systematically assess how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the occupational health and safety of Environmental Health Professionals. Understanding the types and severity of hazards they faced and evaluating the adequacy of protective measures can inform targeted interventions and policy reforms. This study, therefore, assessed the occupational hazards and safety risks encountered by Environmental Health Professionals (EHPs) in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic and examined the existing training, resources, and support (or lack thereof) provided to mitigate these risks. It also sought to identify any gaps in OHS policy or practice that affect this workforce, to inform the development of measures that protect EHPs and similar workers in future public health emergencies.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

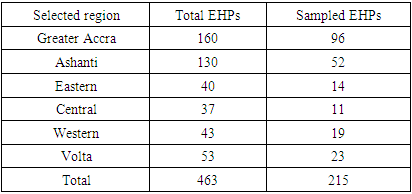

- We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional study using a mixed-methods approach. The study focused on Environmental Health Professionals working in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021). Ghana is administratively divided into sixteen regions. For this study, six regions were purposively selected based on high COVID-19 case counts and the presence of active EHP involvement in pandemic response. These included both the most populous urban regions, such as Greater Accra and Ashanti, as well as others from various parts of the country, including the Western, Eastern, Central, and Volta regions. This approach, which focuses on regional capital cities and municipalities with high infection rates, allowed the study to capture a comprehensive view of the experiences of EHPs across various local areas. For instance, EHPs sampled in the Volta region included those in the Ho Municipality, the regional capital, which provided useful information on the situation in that mid-sized city. Meanwhile, Greater Accra and Ashanti provided data from major metropolitan centres. Within each selected region, we collaborated with the Regional Environmental Health and Sanitation Units to identify specific Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Assemblies (MMDAs) that were heavily involved in COVID-19 management efforts. Thirteen MMDAs were included in total (two from each region, except for three from Greater Accra due to its higher disease burden). These comprised mainly large urban municipalities (e.g., Accra Metropolitan and Kumasi Metropolitan) and a few smaller districts, to ensure diversity. These MMDAs had the highest COVID-19 cases in the selected regions.

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

- The target population consisted of all Environmental Health Professionals in the selected MMDAs who were actively involved in the COVID-19 response. In Ghana, the EHP workforce is organised into different ranks: Environmental Health Assistants (EHA) at the certificate level, Environmental Health Officers (EHO) at diploma level and Technologists (EHT) at Bachelor level, and Environmental Health Analysts at graduate and postgraduate level. The study targeted respondents in all these ranks to determine if experiences differed by position or seniority. The 13 MMDAs in the six selected regions had a total of 463 Environmental Health Professionals. Based on this, Slovin’s formula was used to calculate the sample size, as shown in Equation 1.

| (1) |

|

2.3. Data Collection

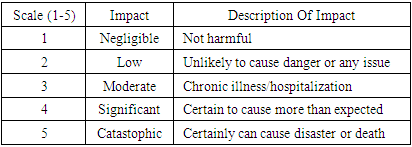

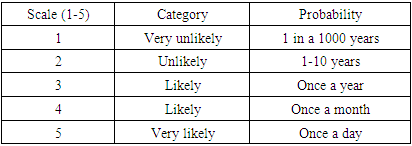

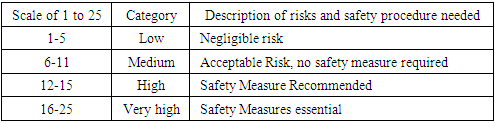

- Quantitative data were collected using a structured questionnaire informed by literature on occupational hazards among health professionals and adapted to the COVID-19 context. It covered several thematic areas, including demographics, COVID-19-related duties, occupational hazards experienced, OHS training and knowledge, availability of PPE, support systems, and policies or guidelines related to COVID-19.To determine the risks associated with their activities, each EHP was asked to outline the hazards related to the activities they were engaged in and estimate the likelihood and severity of the hazards. The likelihood and severity were scored on a scale of 1 to 5 as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

|

|

| (2) |

|

2.4. Data Analysis

- For the quantitative data, descriptive statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 25). Frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and means for continuous variables, as appropriate, were computed. Key outcome variables included the prevalence of various hazard experiences (injuries, infections, etc.) and the availability of training, personal protective equipment (PPE), and support. These were stratified by subgroups (e.g., by rank, gender, or region) to observe any differences. Bivariate associations were tested using the chi-square (χ²) test for categorical variables. For instance, we examined whether rank (junior vs. senior) was associated with injury occurrence and whether gender was associated with the likelihood of reporting injuries or stress. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for these exploratory analyses.The qualitative data from FGDs and KIIs were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically using NVivo software. Initially, two researchers read through the transcripts independently and open-coded the data to identify emergent themes and patterns. Codes were then compared and harmonised into a coding framework that captured major themes, including “perceived hazards,” “emotional impact,” “workplace support,” “coping strategies,” and “suggestions for improvement.” We paid special attention to recurring sentiments and any important quotes that illustrated the experiences of EHPs. Triangulation was achieved by comparing qualitative results from FGDs and KIIs with survey findings to ensure consistency and enrich interpretation.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

- Permissions were obtained from the Regional Environmental Health authorities and the management of each participating MMDA. All participants provided informed consent. For the survey, consent was implied by voluntary completion after reading the information sheet. For interviews and focus group discussions (FGDS), written or verbal (recorded) consent was obtained. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time or skip any question with which they were uncomfortable. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained; no individual names or personal identifiers appear in any reports or publications. Data were stored securely with access limited to the research team. Given the potential sensitivity (especially for qualitative comments critiquing the employer or government), extra care was taken to report findings in aggregate or anonymised form.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

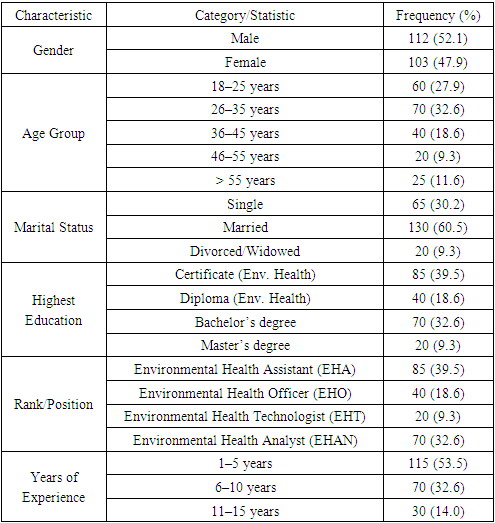

- A total of 215 Environmental Health Professionals participated in the study. Table 5 shows their demographic and professional profiles. A little more than half (52%) were male, with a mean age of approximately 34 years. The largest age group was 26–35 years (33%), followed by 18–25 years (28%); relatively few officers were above 45 years old (~21%). Approximately two-thirds (61%) of respondents were married, while a third (30%) were single, and the remainder were either divorced or widowed. Households were typically family-based, with about three-quarters (72%) living with a spouse and/or other family members, while almost a quarter (28%) lived alone.

|

3.2. Involvement in COVID-19 Response Activities

- All respondents reported being actively engaged in multiple aspects of the COVID-19 response as part of their regular duties. They took part in contact tracing by visiting or calling the contacts of confirmed cases to monitor symptoms and ensure quarantine compliance; delivered health education through community sensitisation and risk communication at markets, bus stations, schools, and other public venues; carried out fumigation and disinfection by spraying chlorine or other disinfectants in locations such as markets, offices, schools, and mortuaries; and joined safe burial teams to handle and transport the bodies of those who died from COVID-19 and responsible for disinfecting burial sites.Each respondent indicated the activities they were personally engaged in. Figure 1 shows the percentage of officers involved in each task.

| Figure 1. Proportion of respondents involved in COVID-19-related tasks |

3.3. Occupational Health Hazards and Safety Risks

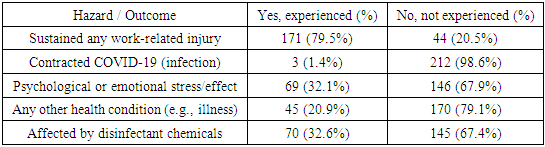

- Nearly 80% of respondents reported sustaining at least one injury (Table 6). Injuries ranged from minor cuts, falls, and musculoskeletal strains to deep lacerations or back injuries incurred while lifting heavy bodies or coffins. Many of these injuries occurred during burial operations when officers slipped on wet surfaces, strained their backs in full PPE, or were pricked by sharps in the course of duty. More than a tenth (13%) of those involved in contact tracing noted hostile encounters that sometimes escalated into assaults. Despite the high exposure, only three officers (1%) tested positive for COVID-19, each experiencing mild illness and recovery. This may reflect diligent PPE use during burials and outdoor tasks, or limited testing and underreporting, as many officers were only tested when symptomatic. Psychologically, roughly one-third (32%) reported anxiety, insomnia, persistent fear, or emotional exhaustion. This was often tied to worries about infecting family members or to community stigma that labelled them “COVID-19 undertakers”. The remaining two-thirds credited peer support and personal coping strategies (such as religious faith or humour) with preserving their mental well-being. About 1 in 5 officers reported other health complaints such as chronic coughs, worsened asthma, fatigue, weight loss, or exacerbated hypertension or diabetes. These were linked to stress or chemical exposures, and almost one-third (33%) experienced acute effects such as eye and throat irritation, dizziness, headaches, or rashes from fumigation chemicals. Officers sometimes ran out of respirator cartridges or resorted to using surgical masks. Despite this, about two-thirds (67%) of officers did not experience significant chemical-related issues (Table 6). This suggests that many precautions were effective or that exposure durations were short. Generally, the findings indicate that the responsibilities associated with the pandemic have put Environmental Health Professionals (EHPs) in physically demanding and occasionally hazardous environments, exposing them to immediate injuries as well as potential long-term physical and mental health risks.

|

|

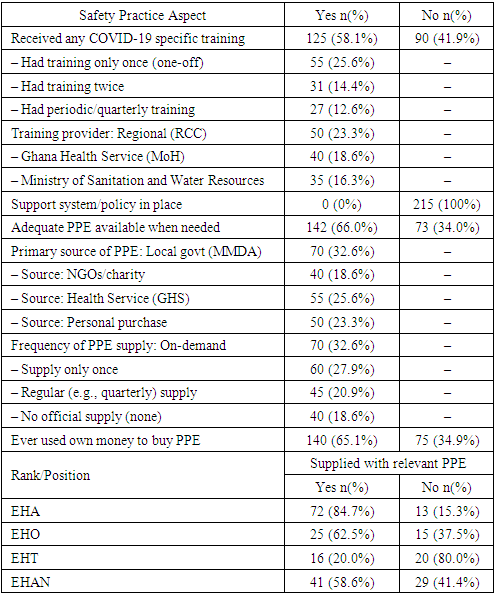

3.4. Training and Safety Practices

- A slight majority of the EHPs (58%, n = 125) reported that they had received some form of training specifically related to COVID-19 (Table 8). Such training typically covered topics such as infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, the proper use of PPE, case definition and the basics of contact tracing and safe burial protocols. Of those who were trained, it was mostly a one-time training session at the onset of the pandemic, as about a quarter (26%) of all respondents reported having been trained only once. Just about one-tenth (13%) had quarterly or regular refreshers. Thus, training frequency was low. The Regional Coordinating Councils (RCCs) were the most cited organisers of training (23%), likely through regional emergency response committees. Some training was provided by the Ghana Health Service (19%) and the Ministry of Sanitation and Water Resources (16%), showing a multi-agency approach. Still, 2 in 5 officers received no training at all, which may have left them initially ill-prepared. Key informants in interviews acknowledged the gaps, noting that trainings often targeted higher-level staff who were then supposed to cascade knowledge to others. This, however, did not always trickle down to reach everyone.

|

4. Discussions

- This study highlights the occupational health hazards and safety risks among Environmental Health Professionals in Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the most striking results was that nearly 80% of EHPs reported sustaining physical injuries in the line of duty. This injury rate is more than twice the global prevalence of occupational injuries (36%) among sanitation workers [15]. It is, however, comparable to occupational injuries among sanitation workers in non-pandemic settings [16]. The similarity suggests that the physically demanding nature of sanitation and environmental health work inherently carries a high risk of injury. In our study, tasks such as carrying coffins and operating in hazardous environments (slippery floors in morgues, uneven terrain in cemeteries) likely compounded those risks. The high injury toll highlights the need for improved protective measures, including ergonomic training and equipment, for EHPs. Only 1% of the officers contracted COVID-19, which is relatively low compared to a prevalence of 9% among Ghanaian medical doctors [17]. This confirms their reports that they were generally diligent in using PPE and taking precautions. However, the fear of infection was disproportionately high compared to the actual infection rate – a phenomenon observed in many healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. The psychological burden reported (32% affected) might stem from the uncertainty and visibility of the threat. At the start of the pandemic, workers experienced tremendous fear about the potentially deadly virus. Studies elsewhere have shown that psychological distress was common among health workers even if they did not end up contracting the virus, due to perceived risk and witnessing fatalities [18-21]. Our qualitative findings (officers afraid for their families, reluctant to have regular interactions) reflect a similar trend. This points to the importance of psychosocial support and accurate risk communication for frontline workers. Even if the objective risk (infection rate) is low, managing fear and stress through counselling or peer support groups could improve their mental well-being.The most critical finding, perhaps, is the complete absence of formal support systems for EHPs in Ghana during the pandemic. No officer was covered by any additional insurance or employee assistance programme for COVID-19, and none of the local government units had a health and safety policy in place. This is consistent with the broader situation that Ghana’s workforce often operates without explicit OHS policies [22]. It also resonates with World Bank observations that sanitation workers have “little to no legal protection” [23]. The neglect of EHPs in the distribution of incentives (e.g., exclusion from tax waivers and allowances given to health ministry staff) was demoralising and arguably inequitable, considering EHPs also risked their lives. From a policy perspective, this points to a fragmentation in Ghana’s approach to frontline workers – those under the Health Ministry were recognised, but those under Local Government (such as EHPs) were overlooked. A lesson here is that future public health emergency plans must adopt an inclusive definition of “frontline health workers” to ensure all key contributors receive support. The Ghanaian government and local authorities should institutionalise OHS measures for all departments.The finding that one-third had inadequate PPE and two-thirds spent their own money on PPE shows systemic supply chain and budgeting issues. During the early stages of the pandemic, PPE shortages were global [24,25], but by mid-2020, Ghana had received donations and ramped up its procurement efforts. However, those resources did not consistently trickle down to every EHO on the ground. Key informants mentioned that inadequate PPE directly hampered EHO effectiveness – officers would slow down activities or limit their daily cases to conserve PPE. Moreover, as literature [5] indicates, improvised or extended use of PPE can introduce new risks. For instance, reusing single-use masks or wearing an N95 for an entire day can reduce their effectiveness and cause discomfort or skin damage [26]. This showcases the importance of ensuring a reliable supply of PPE to all frontline units, not just hospitals. The findings of this study suggest that rank or professional role significantly influenced access to PPEs during the COVID-19 pandemic among environmental health professionals in Ghana. EHAs, who had the highest level of access (85%), are often deployed directly in the field to enforce public health regulations, disinfect public spaces, and support contact tracing. Their exposure to potential sources of infection likely made them a high priority for PPE allocation. This finding is consistent with [27], who reported that frontline health workers in Ghana received higher levels of PPE than support or administrative staff. In contrast, Environmental Health Technologists (EHTs) had the lowest access to PPEs (20%) despite their technical roles. This discrepancy mirrors the findings from a U.S.-based study by [28], which noted that early in the pandemic, PPE was distributed unevenly, with a strong focus on clinicians and field-facing personnel, leaving many technical and support staff under-equipped. In future responses, logistics planning should include the environmental health workforce from the outset, quantifying their PPE needs for various operations (such as spraying and burials), establishing a dedicated pipeline and ensuring equitable distribution.More than 40% of officers had no COVID-specific training, and most of the rest received only a single briefing. This is a clear gap in capacity building. Training is known to improve workers’ confidence and performance in health emergencies [29]. Those who were trained likely benefited – our qualitative feedback suggests that trained officers felt more prepared and were able to help mentor others. However, the uneven training coverage meant some EHPs learned through trial and error. Past studies in emergency management emphasise that ad-hoc learning can lead to avoidable mistakes and exposures [30]. Thus, a recommendation is that during health emergencies, regular, even brief, refresher training be institutionalised, possibly on a quarterly basis, as some regions have attempted.

4.1. Study Limitations

- As a cross-sectional survey, the data capture a snapshot in time (mostly in 2021) of EHPs’ experiences and rely on retrospective self-reporting. Therefore, we cannot establish causality or temporal changes. A longitudinal design (following officers over the course of the pandemic) could have provided a better understanding of how hazards and responses evolved over time, but it was beyond our scope. The study focused on six regions with high COVID-19 cases and included 13 MMDAs. Although the study covered a range of settings (urban and semi-urban), the findings may not be fully generalisable to all parts of Ghana. Data on injuries, infections, likelihood and severity of hazards are self-reported. Therefore, there is a possibility of recall bias – officers might forget minor incidents or, conversely, recall events with exaggeration due to emotional impact.

5. Conclusions

- This study brings to the fore the occupational health and safety risks faced by EHPs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings reveal that EHPs in Ghana played vital, yet largely unrecognised, roles in the COVID-19 response, conducting contact tracing, public education, disinfection, and safe burials. They faced high levels of physical harm, many reporting injuries or illness, as well as significant psychological stress related to fears of contagion and heavy workloads. Severe institutional gaps exacerbated these occupational risks: most officers received little or no specialised training for pandemic tasks; frequently lacked sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), forcing many to purchase supplies out of pocket; and operated without formal occupational health and safety (OHS) policies, mental-health support, hazard pay, or even health-insurance coverage. Female EHPs reported higher injury rates, and younger officers were more likely to self-fund PPE, showcasing inequities within the workforce.To address these shortcomings, the study recommends that EHPs be formally integrated into emergency response planning, with guaranteed access to training, PPE, and inclusion in any health worker incentive schemes. Local and national authorities must develop and enforce comprehensive OHS guidelines covering infection control, ergonomic injury prevention, and psychosocial support (e.g., counseling or peer networks). Strengthening collaboration between the Local Government Service and the Ghana Health Service will be essential to ensure that EHPs are not excluded from pandemic trainings or resource distributions. Future research should include more regions and adopt a longitudinal design to track improvements and changes over time. Additionally, comparative studies with EHPs in other countries or sanitation workers could place Ghana’s case in an international context.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors acknowledge the support of the Regional, Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Environmental Health Professionals in the six selected regions, who assisted with data collection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML