-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2025; 15(1): 10-14

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20251501.02

Received: Feb. 13, 2025; Accepted: Mar. 6, 2025; Published: Mar. 28, 2025

To Study the Attitude of Indian Urban Population Towards Cervical Cancer and Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination

Aliya Shetty Oza

Grade11 IBDP, Jamnabai International School, Mumbai, India

Correspondence to: Aliya Shetty Oza, Grade11 IBDP, Jamnabai International School, Mumbai, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. India alone accounts for over 20% of the cervical cancer cases globally with one death occurring every seven minutes. Persistence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in the female genital tract is the leading cause of cervical cancer. The effectiveness of the HPV vaccine in protecting against precancerous and cervical cancer is well-documented. Subsequent to recommendations by the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization and development of Cervavac, an affordable and effective Indian developed vaccine, the government recently announced a national drive to vaccinate all girls between nine to fourteen years. Methods: An online survey was conducted by circulating a google document among students and parents from a local school in the suburbs of Mumbai. There was a total of 198 responses with 27 males and 171 females. Questions about the cause, predisposing factors, prevalence, screening of cervical cancer, availability of the vaccine, readiness to get vaccinated and gender neutrality in receiving the vaccination were addressed. Findings: 93.4% of the participants were aware that cervical cancer is a cancer in women affecting the female genital tract. 98% participants agreed that cervical cancer is common in both rural and urban areas. Though 65.7% participants knew that the risk of cervical cancer is higher with multiple sexual partners, only 50% were aware that it is caused by an infectious agent. Only 26.3% participants knew that cervical cancer is an aggressive cancer with high fatality. 62.1% said that cervical cancer is fatal only in the later stages. 50% thought that the vaccine is only useful in girls to prevent cervical cancer. Interpretation: The study reveals the lack of adequate information regarding cervical cancer among the participants who belonged to affluent suburbs in an urban city. It highlights the need to conduct similar studies in rural areas too. Such studies will help healthcare policymakers to plan educational activities. Accurate information is required to create awareness and improve acceptability when the vaccine is rolled out as part of the national program.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, Cervical cancer, HPV vaccine

Cite this paper: Aliya Shetty Oza, To Study the Attitude of Indian Urban Population Towards Cervical Cancer and Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination, Public Health Research, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 10-14. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20251501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide and the second most common female cancer in India accounting for 10% of all cancers in women [1]. India alone accounts for over 20% of the cervical cancer cases globally with one death occurring every seven minutes [2]. Though we are aware of cancers caused by lifestyles like smoking, drinking alcohol, and ultraviolet radiation, few know that a large variety of common cancers are also caused by infectious agents like bacteria and viruses. Persistence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in the female genital tract is the leading cause of precancerous lesions in the cervix and ultimately cervical cancer. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide (almost 80%). Most people who are sexually active will contract the virus during their lifetime. But it does not cause symptoms in the majority and is resolved by our immune systems (70-90%) [3]. However, recurrent and/or persistent infection can lead to the development of cancer over time. This is especially true for infection with certain high-risk strains of HPV.The fact that cervical cancer is caused by a virus has provided an opportunity to develop a vaccine to provide protection, just like we have vaccines to protect us from infections like the COVID or influenza. The effectiveness of the HPV vaccine in protecting against precancerous and cervical cancer is well-documented through multiple randomised controlled trials [4]. A population-based study conducted in England observed a substantial reduction in cervical cancer in young women after the introduction of the HPV immunisation programme, especially in individuals who were offered the vaccine at age 12-13 years. Also, the HPV immunisation programme has successfully almost eliminated cervical cancer in women born since Sept 1, 1995. The latter finding holds the promise of global elimination of cervical cancer through widespread vaccination. It could be a turning point in management of preventable cancers [5].The stage of the disease at diagnosis is an important prognostic factor. The 5-year survival rate ranges from 91% in stage one cancer to 19% in stage four cancer, highlighting the importance of early detection [2].Additionally, the HPV is also implicated in anogenital cancers and head neck cancers. Approximately 5% of the world's cancers are specifically attributed to HPV [6]. These cancers kill, reduce quality of life and burden our healthcare system. Thus, it is critical to improve gender-neutral HPV vaccination. Though the HPV vaccine has been around for a few years, the coverage is limited in India. The reasons include ignorance about the vaccine and cervical cancer, the cost of the vaccine, limited availability, fear of side-effects and so on. The National Technical Advisory Group on Immunization, the highest advisory body on immunisation in India, recommended incorporating the HPV vaccine into the universal immunisation program on June 28, 2022. Additionally, Cervavac, an affordable and effective Indian developed vaccine was officially launched on September 1, 2023. Subsequently, the country announced a national drive to vaccinate all girls between nine to fourteen years.With this background, the current study aims to study the knowledge and attitude of urban population towards cervical cancer and the acceptance of this vaccine for themselves and their family.

2. Method

- An online survey was conducted by circulating a google document among students and parents from a local school in the suburbs of Mumbai. There was a total of 198 responses; there were no exclusions. The participants’ age ranged from 12 to 59 years and included 27 male and 171 females. The questionnaire included questions about the cause, predisposing factors, prevalence, and screening of cervical cancer. Also, there were questions about the availability of the vaccine, readiness to get vaccinated and gender neutrality of receiving it.

3. Results

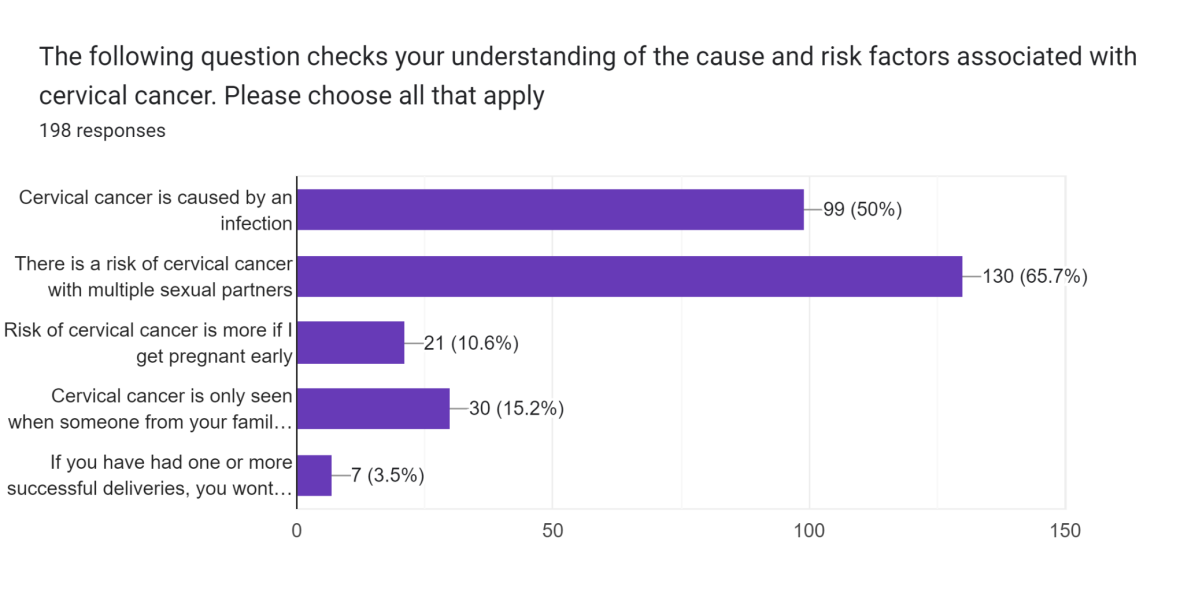

- 93.4% of the participants were aware that cervical cancer is a cancer in women affecting the female genital tract. 194 participants out of 198 i.e., 98% participants agreed that cervical cancer is common in both rural and urban areas.Though 65.7% of participants knew that the risk of cervical cancer is higher with multiple sexual partners, only 50% were aware that it is caused by an infectious agent. 15.2% of participants said that cervical cancers only run in families or there can’t be any sporadic cases. 10.6 % thought that early pregnancy predisposes to cervical cancer and 3.5% of participants felt that successful deliveries do not protect against cervical cancer. See Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Question on risk factors |

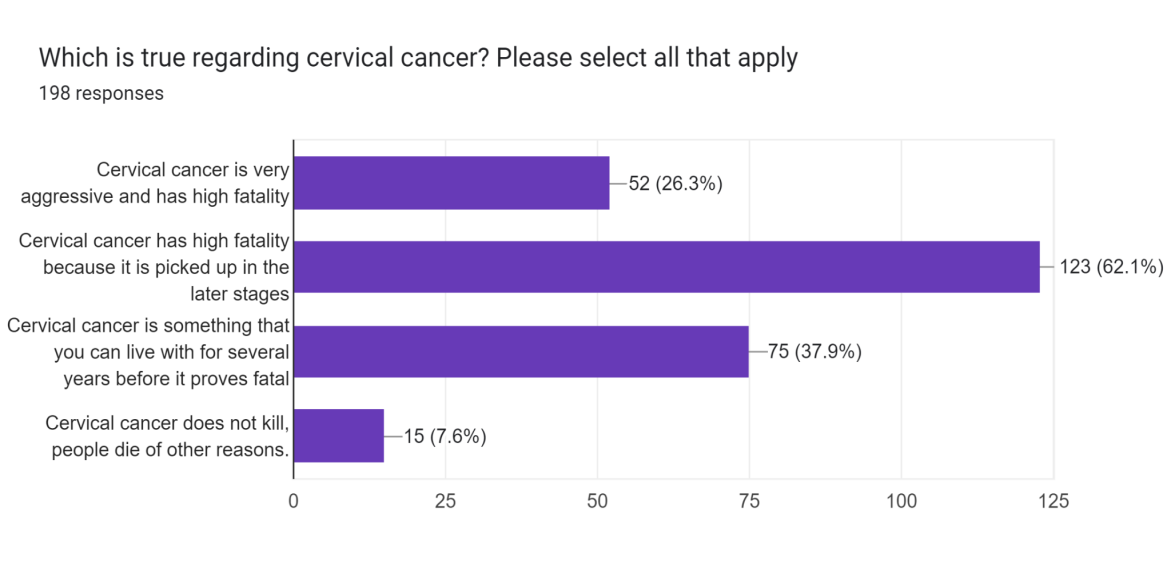

| Figure 2. Prognosis of cervical cancer |

4. Discussion

- The study tried to understand the level of information and attitudes of urban communities in their reproductive age towards cervical cancer and HPV vaccination. The survey highlights that several participants knew that cervical cancer is a common cancer in women. They also knew few of the high-risk behaviours predisposing to developing the cancer. A positive finding was that the large majority knew that cervical cancer is preventable and that there is a screening test in the form of cervical PAP screening test.However, half of the participants were unaware of the cancer having an infectious aetiology or that it was caused by a virus, the human papillomavirus. Also, only about one-fourths of the participants knew that cervical cancer could cause death. Close to 45% participants thought that cervical cancer was a slow indolent cancer which does not prove fatal until several years. Of these 7.6% participants felt that cervical cancer does not kill. Thus, the study reveals the lack of adequate information regarding cervical cancer among the participants who belonged to affluent suburbs in an urban city. It also highlights the need to conduct similar studies in rural areas. Such studies will help healthcare policymakers to plan educational activities. Accurate information is required to create awareness and improve acceptability when the vaccine is rolled out as part of the national program. The high-income countries have reduced the incidence of cervical cancer through sexual health education, better healthcare systems with good access to screening, early detection and treatment and vaccination. Consequently, cervical cancer is now a disease of low middle income countries (LMIC) with weaker healthcare systems, poor screening and vaccination outreach, and limited sexual health education. Additionally, healthcare inequalities aggravate the problem. So, the current study has great relevance in the context of LMIC. Similar studies in other low and high-income countries show comparable results. A community-based study in Ethiopia studied the attitudes of parents towards HPV vaccination in girls. The study found that the knowledge and willingness of parents toward the HPV vaccine were low. The study recommended that the health officials should boost HPV vaccination promotion through public media and campaigns at public places like schools and religious places [7].Another study in Singapore found that barriers and facilitators exist at different levels to influence vaccine uptake. A school-based national vaccination programme was proposed to increase the rate of uptake of HPV vaccination in Singapore [8].However, some studies have shown that brief educational tools have only limited effects on increasing the willingness of parents to vaccinate their daughters. This suggests that other educational strategies need to be explored. A study conducted in Japan studied whether providing additional information to parents who have children eligible for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination can help in overcoming vaccine hesitancy. They used a cervical cancer survivor's story to assess the effect on the willingness of parents to get HPV vaccination for their daughters. The study found that the story increased immediate willingness to consider HPV vaccination, but the effect did not last for more than three months [9]. The study highlights the importance of exploring novel educational and motivational methods to ensure that the HPV vaccination program is well-accepted and is a success. There are several studies that have found the HPV vaccine to be effective in preventing the development of invasive or advanced cervical cancer. One of the studies found that women from more deprived areas benefit more from vaccination than those from less deprived areas [10]. The success of this program can not only save several lives and improve quality of life, but it will reduce the burden of cervical cancer on the healthcare system too.

5. Strengths and Limitations

- The study addressed several questions regarding cervical cancer and HPV infection by using a simple survey. The questions tried to cover the understanding about the cause, risk factors, availability of screening tests and vaccines, burden of the disease in terms of prevalence and mortality, and the protective effect of the vaccine in all genders. The participants were informed at the start regarding the nature of questions in the survey. Consent was recorded, and they could abort the study anytime. The responses were recorded anonymously. So, it was an ethically acceptable study.Though a short study, several important insights could be derived from the data. It reflected the lack of complete and accurate information regarding the severity of the disease and need for vaccination, while highlighting better understanding of some other characteristics of the cancer like risk factors. However, the sample size was small consisting of only 198 respondents. It was up to the discretion of people with whom the survey was shared to participate or not. So, the sample may not completely represent the urban population of Mumbai. Additionally, the survey was circulated largely among students and parents of a particular school in the suburbs of Mumbai. The gender of participants was skewed in favour of females. So, the representativeness of the sample is restricted.Similar studies are required not only in the urban areas but also in second and third tier cities and villages to gauge the true attitude of people in India towards vaccination. Such data will better reflect the current acceptance level of the vaccine which is being rolled out as a national campaign. It will also guide the government in planning outreach programs and information spreading activities using social media, mass media etc.

6. Conclusions

- The current study aimed at understanding the existing knowledge of people about HPV, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccination in an affluent urban community in a metropolitan city. The study highlights that the information and attitudes towards cervical cancer and HPV vaccine is inadequate. It parallels the findings of similar studies conducted in developing countries and highlights the need to undertake novel educational activities and campaigns to educate the citizens. The policy makers need to factor such educational activities while rolling out the HPV vaccination as part of the National Immunisation Program.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Dr Kavita Ramanathankavitaap2@gmail.com

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML