-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2022; 12(5): 110-123

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20221205.02

Received: Nov. 15, 2022; Accepted: Dec. 2, 2022; Published: Dec. 14, 2022

Situation Analysis on the Quality of Maternal and Child Health in Nairobi and Garissa County in Kenya

Caroline Kawila1, 2, Daniel Mwai2, 3, Easter Olwanda2, 4, Wangui Muthigani2, 5, Ednah Mwangi2, Wesley Rotich2, David Njuguna2, 5

1Department of Health System Management, Kenya Methodist University, Nairobi, Kenya

2Futures Health Economics and Metrics Ltd

3University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

4Centre for Microbiology Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya

5Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Caroline Kawila, Department of Health System Management, Kenya Methodist University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

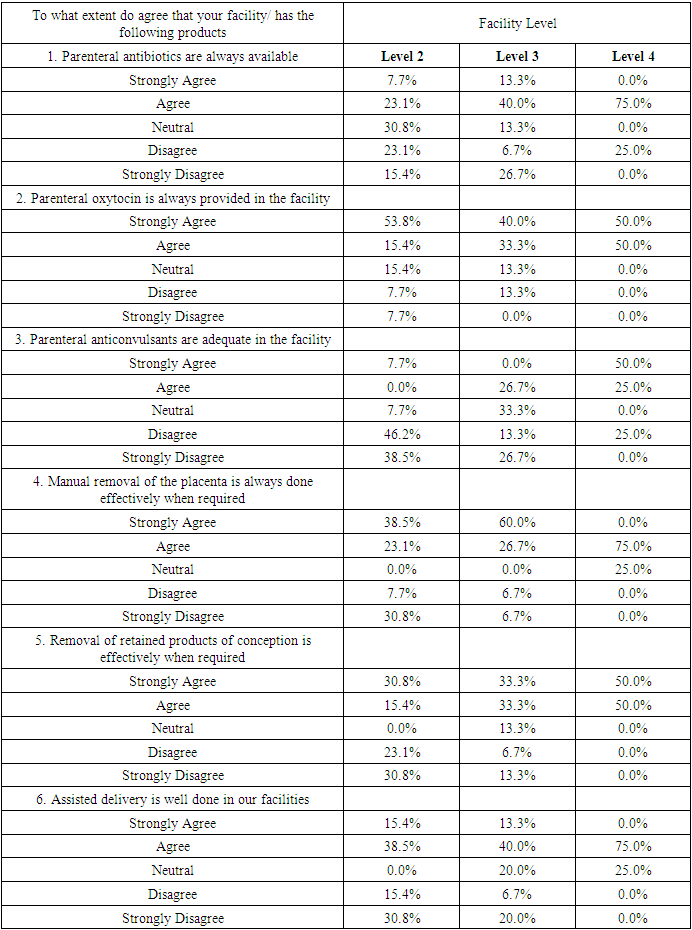

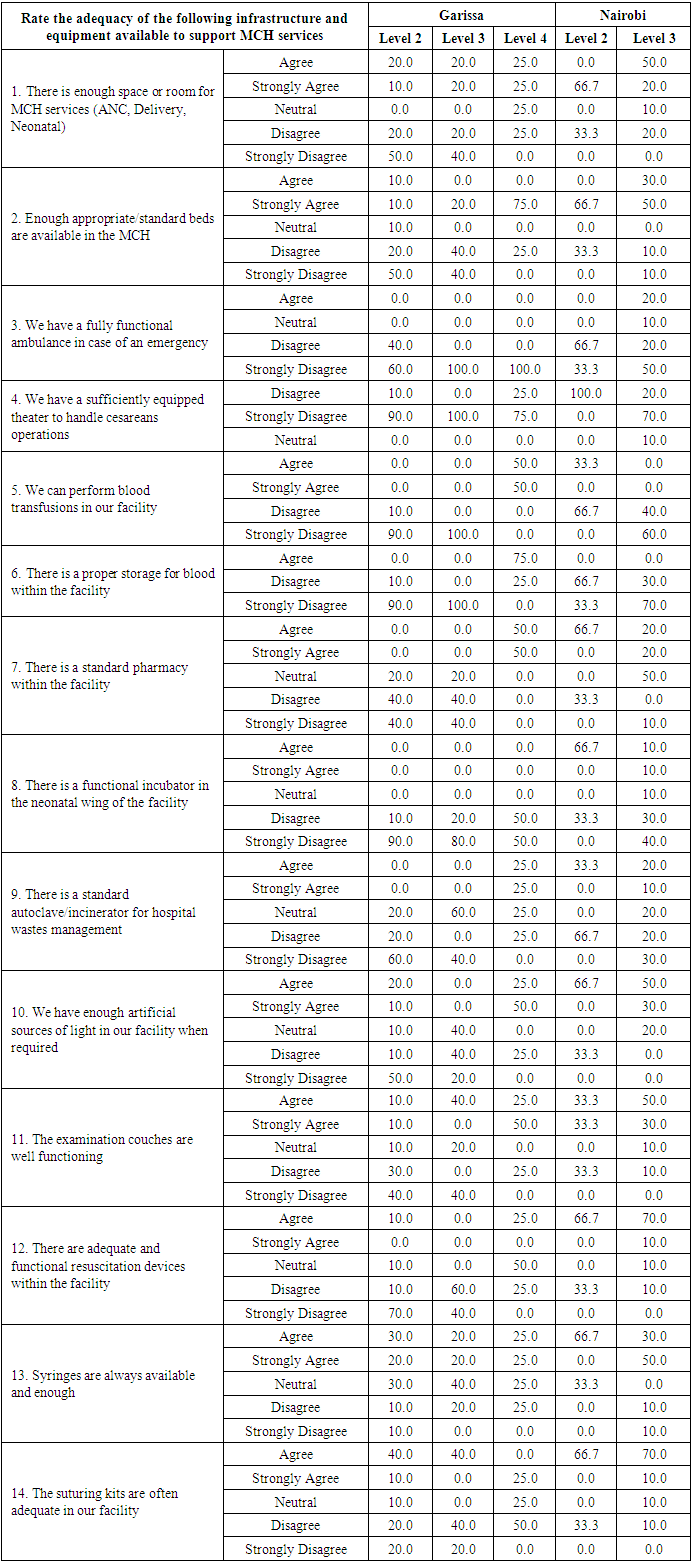

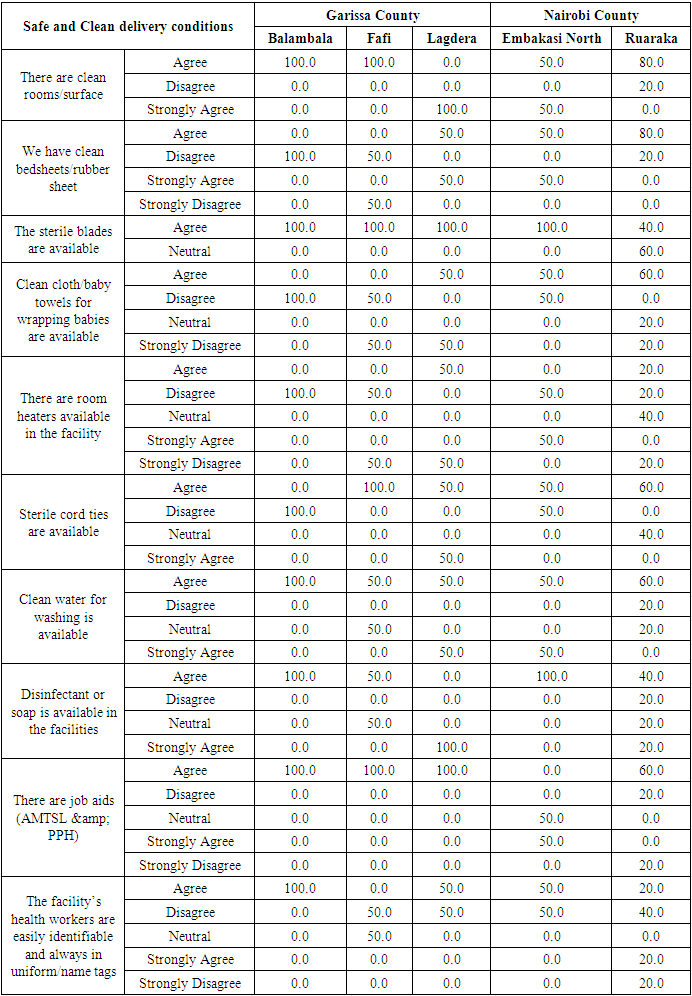

Maternal and Child Health is a Global Health Priority. Interventions to improve and strengthen maternal health outcomes are numerous and seek to scale-up uptake and quality. Quality improvements reflect on three health systems goals: improving maternal and child health service delivery, financial risk protection, and responsive care. Access to quality maternal health care for the public contributes significantly to their well-being by making them a productive part of society. Challenges reported in different studies hindering quality maternal and child services include disrespect and abuse during childbirth, long waiting and travel times, and inadequate resources. Excellence in healthcare service contributes to the reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality, and its incidence may be related to substandard healthcare services and the skills of healthcare providers, yet maternal and child health services are fundamental to population health. Approach: Using a mixed-method cross-sectional study design, a structured questionnaire, an observation checklist, and focus group discussions were used to collect data. A purposive sampling technique was used to identify respondents offering and receiving maternal and child healthcare services. Data were managed and analyzed using SPSS version 25. The situation analysis was carried out in Garissa and Nairobi counties with the objectives to identify geographical areas where populations are most in need and with limited/absent access to maternal newborn, and child health care services and understand the main vulnerabilities of Maternal Child Health (MCH). Results: The results disclosed that Maternal and Child Health services were available in the geographic areas studies i.e. Garissa and Nairobi Counties, however, it was evident that there was a need to have MCH resources improved for better health outcomes. The main vulnerabilities in MCH included poor access, inadequate availability of maternal medicine, compromised space or room for ANC and neonatal service delivery, inadequate availability of infrastructure and equipment, lack of enough essential medical supplies, and cost of associated maternal and child health services. The quality of MCH services was mostly hindered by both patient and organizational factors for example unable to get to a health amenity in time, and insufficient infrastructure, equipment, and medical supplies. There is a need for stakeholders to invest in strengthening patients’ knowledge and , provide adequate medical equipment and supplies as enablers of access and use of MCH services across all levels of care.

Keywords: Maternal and Child Health, Quality, Access, Situational analysis, Kenya

Cite this paper: Caroline Kawila, Daniel Mwai, Easter Olwanda, Wangui Muthigani, Ednah Mwangi, Wesley Rotich, David Njuguna, Situation Analysis on the Quality of Maternal and Child Health in Nairobi and Garissa County in Kenya, Public Health Research, Vol. 12 No. 5, 2022, pp. 110-123. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20221205.02.

1. Introduction

- In Kenya, public health amenities struggle to provide basic services owing to human resource challenges, inadequate commodities attributed to poor inventory management and supply chain management practices, poor financing of health systems, weak institutional arrangements, and under developed organizational ethics codes (Waithaka et al., 2020). Agreeing to a World Health Organization (WHO) report (2018), there has been a 25-year of global decline (44%) of MMR to around 216 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015 from 385 in 1990. The 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Results pointed to slow progress in maternal, neonatal and child health outcomes with a maternal mortality ratio of 355/per 100,000 live births, an infant mortality rate of 35.5/per 1000 live births, and an under 5 mortality rate of 52/1000 live births(KNBS, 2019). The rate of decline is slow such that the attainment of sustainable development goals targets is unlikely (SDG target 3.1 for maternal mortality is 70/100,000 live births and for neonatal mortality (SDG target 3.2) is 12/1000 live births) (World Health Organization, 2015). Empirical studies have confirmed that antenatal care (ANC) visits, institutional delivery with skilled birth attendants (SBA), and postnatal care are vital in preventing maternal and newborn deaths (Gülmezoglu et al., 2016). Inequality in the provision and access to health services for mothers and children is prevalent in Kenya. Geographic accessibility from home to health facilities is considered a major barrier to access to adequate maternal and child health services (Tanou et al., 2021). The negative association between distance or travel time to health facilities and use of health services has been shown to be a significant barrier to access to health services. This is because many life-saving interventions, such as caesarean sections and blood transfusions, are only available at the medical facility to which they are referred (Tounkara et al., 2022). This geographical barrier is represented by the second delay in the 3-delays model. (1) Delays in decision making, (2) delays in reaching medical facilities, and (3) delays in adequate care. (Mohammed et al., 2020). Besides, good infrastructure according to (Quattrochi et al., 2020; Sgaier et al., 2015), is essential not just for persons seeking healthcare services but also for easy distribution of medical products and faster referrals in case of emergencies. Inadequate resources have an impetus on facility outcomes such as quality and safety of care delivered. Community-based interventions can significantly reduce neonatal and maternal mortality (Lassi et al., 2010).Similarly, tracer item availability is low, suggesting the need to expand coverage in primary health care settings to accelerate and achieve reductions in maternal and neonatal mortality and meet SDGs 3.1 and 3.2. In Kenya 50% of facilities offer delivery services with significant gaps in the availability of tracer items for Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (CEmONC) and Basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) services. This compromises the availability and quality of a lifesaving service to the mother and baby. The mean availability of tracer items required for a facility to be considered ready to offer CEmONC services is 70% with only 1% of facilities having all the tracer items. Similarly, mean availability of BEmONC is 68% nationally with the availability of all tracer items at 3% (MOH, 2019). In 2013, Kenya abolished charges in all public maternity wards, promoting eligible birth attendance and aftercare for newborns and children. The introduction of various health payment schemes, such as the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), Output-Based Aid, Changamuka, Jamii Bora and Linda Mama. It has made it possible for women to have access to appropriate support during childbirth, minimizing long-standing inequalities between urban, rural and poor people. Linda Mama has been developed, improved accountability, and expanded benefits, but beneficiaries still do not have access to some benefits that were part of the revised benefits package e.g newborn care. Therefore, beneficiaries still had to pay out of pocket, and most county health facilities lost their financial autonomy as they were unable to receive reimbursement from NHIF for services rendered. In addition, disbursement of funds from NHIF may be delayed or unpredictable. (Orangi et al., 2021).Furthermore, the inability to quantify and analyze the situation using reliable data plagues Kenya. The health system lacks the ability to measure or understand its own weaknesses and limitations, and policy makers have no science-based idea of what can or should actually be strengthened (Hotchkiss et al., 2010). To facilitate interpretation of national reports and to provide guidance on data use in decision making, (Kihuba et al., 2014) conducted an evaluation of core functions of data generation and reporting within hospitals in Kenya. The study findings indicated that only a few HMIS departments (3/22) had carried out a data quality audit in the 12 months before the survey. Completeness of manual patient registers varied, being 90%, 75.8% and 58% in the maternal-child health clinic, maternity, and pediatric wards, respectively. Vital events notification rates were low with 25.7%, 42.6%, and 71.3% of neonatal deaths, infant deaths, and live births recorded, respectively. Routine hospital reports suggested slight over-reporting of live births and under-reporting of fresh stillbirths and neonatal deaths. The National Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response guideline directs the conduct of Maternal and Perinatal Death Reviews (MPDRs) and near-miss reviews in the community and the health facilities in Kenya. A confidential investigation into the 2017 Maternal Death Report in Kenya found that the majority of audited maternal deaths were poorly recorded and documented. As a result, improving the quality of maternal health requires the use of information technology to facilitate communication and enable faster care and shorter turnaround times. (Delaney, 2018). However, weak ICT infrastructure is evident in low- and middle-income countries. Improving the quality of care for mothers and newborns demands for the health system be prepared in terms of the availability of all resources required (Das et al., 2021; Tunçalp et al., 2015). These factors are part of the drivers to the slow progression in maternal and child mortality that has seen Kenya ranked among the ten most dangerous countries for a woman to give birth in the world (UNFPA, 2020). Counties in the North-Eastern part of Kenya have the poorest maternal indicators with Garissa recording the highest MMR of 641/per 100,000 live births, an IMR of 42.1, and U5MR of 64.6. Nairobi county is reported to have the highest number of absolute maternal mortalities given its population. These two counties are part of the 15 high burden counties for maternal mortality in Kenya. There is a need to maintain investments in MCH care in Garissa and Nairobi counties. However, accelerating progress requires robust and sustainable MCH interventions that are readily adaptable and integrate fluidly into the local systems. Transferability of these MCH interventions relies on evidence-based and context-specific evaluations. One critical weakness across the Nairobi and Garissa counties is the current lack of capacity to effectively monitor patterns of service use through time so that the impacts of changes in policy or service delivery can be evaluated. Moreover, there is a dearth of data on the drivers to poor MCH outcomes in Nairobi and Garissa counties. As such, this situational analysis sought to explore the main vulnerabilities in the two counties, highlighting the ongoing challenges facing their systems and people and to inform and plan interventions that lower maternal, neonatal, and child morbidity and mortality rates.

2. Methods

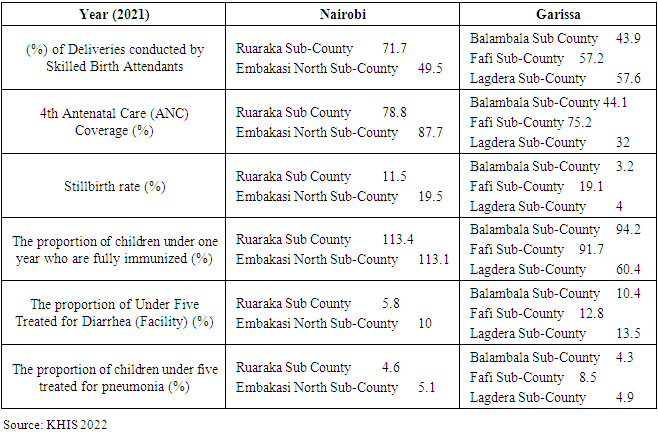

- Study Setting and participantsThis cross-sectional study was conducted in Nairobi and Garissa counties in June 2022. The counties were first purposively selected then cluster sampling followed to select the sub-counties with poor MCH indicators and those in informal settlements in Nairobi. The study sites in Nairobi included Ruaraka and Embakasi North sub-Counties while the study sites in Garissa County included Fafi, Lagdera and Balambala. The MCH indicators for the two counties are summarized in Table 1 below. The target population included county health management teams, men, women, healthcare providers, traditional birth attendants (TBA), chiefs, health records information officers, and community health extension workers. The targeted number of health facilities in Nairobi were nine, while those in Garissa were four.

|

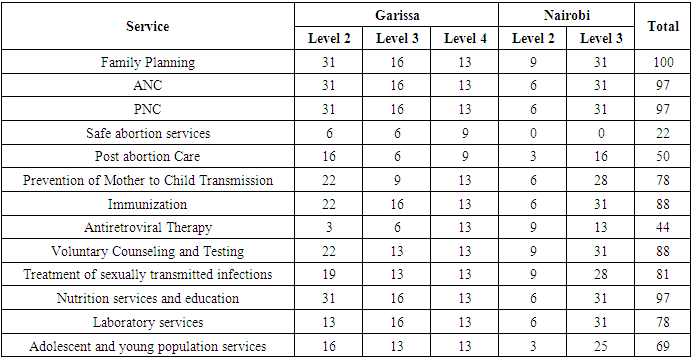

3. Results

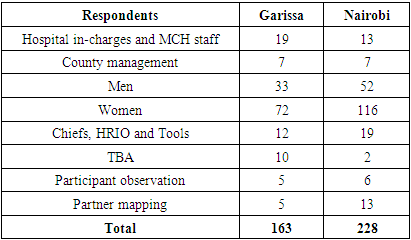

- Study participant characteristicsThis section gives an in-depth description of the findings of the situational analysis. A total of 391 respondents participated in the study. There was a 100% response rate. See Table 2 below for a breakdown of the total number of respondents from Nairobi and Garissa counties.

|

|

|

|

|

|

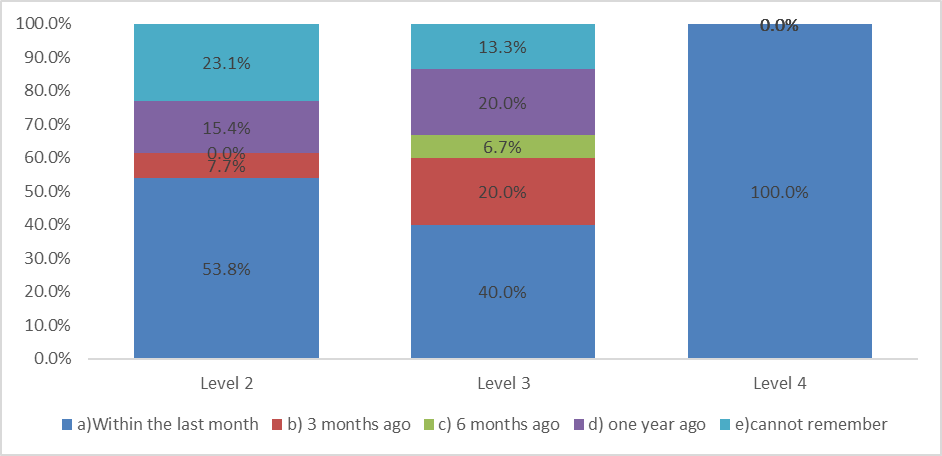

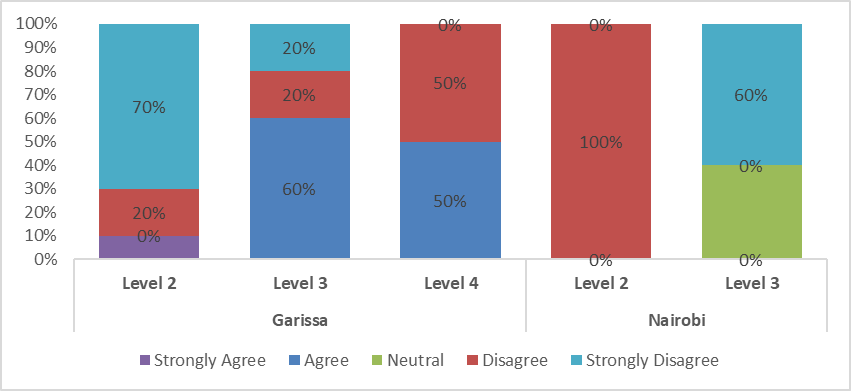

| Figure 1. Health worker training in the MCH |

| Figure 2. Culture and accessing services |

4. Discussion

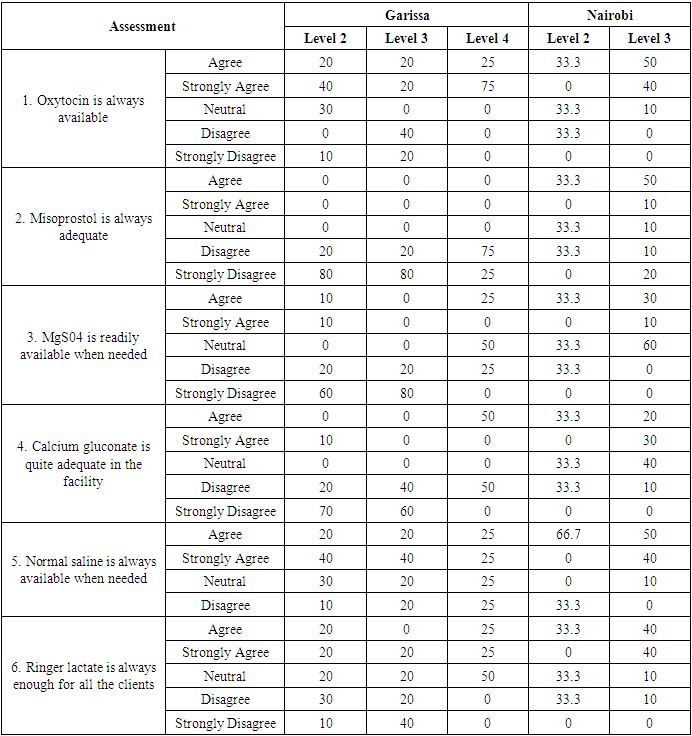

- Quality of health care is the level to which wellbeing administrations for people/populaces improve the probability of wanted wellbeing out- comes (Nady et al., 2018; Hassan & Farag. 2019; Hassan 2020). The results of this study demonstrate major deficiencies in the quality of MCH services in both counties. While the assessed facilities had the seven signal functions of BEmONC, there is a conspicuous lack of infrastructural prerequisites to function at the very basic level in providing essential routine MCH services and emergency care. This finding is consistent with that of several studies that have cited poor infrastructure as a driver to the poor MCH outcomes (Adam et al., 2005; Gerein et al., 2006; Ukachukwu et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 2005). Inadequate MCH infrastructure constrains the capacity to provide quality MCH services in Nairobi and Garissa counties. The lack of available theaters for conducting caesarian sections and the lack of resuscitation equipment for newborns, which bestows the ability to handle obstetric complications is the prime concern. Orji et al. concluded that the major factor causing delay to treatment is theatre-related (Orji et al., 2006). Another issue is the lack of an ambulance for emergency referrals. The Kenya Health Sector Referral Implementation guideline 2014-2018 provides a rationalized framework for a functional county referral mechanism for patients, specimens, and consultants. Unfortunately, the referral system in the country is a major national problem that needs to be addressed urgently. Delays in receiving appropriate facility-based care (delay three), for women facing pregnancy related complications contribute significantly to maternal mortality. A recent enquiry into maternal deaths in Kenya reported that 46.8 of women who died were referred, and 53.2 of these referrals died at the point of the first admission. Securing referral linkages and health facility readiness for rapid and correct patient management are needed to reduce the impact of these delays within the health system (Chavane et al., 2018). In addition, there is a challenge with the transfusion facilities for both counties as they lack proper storage for blood and cannot perform blood transfusions. This has a particular impact on women with pregnancy and delivery-related complications and with severe life-threatening anaemia. Equally noteworthy, is the dearth of legitimate safe abortion services in both counties. Unsafe abortion is responsible for the deaths of nearly 2,600 women and girls in Kenya every year, which translates to seven deaths every day (Report: Lives at Stake as More Kenyan Women and Girls Opt for Unsafe Abortion despite Constitutional Protections |Center for Reproductive Rights, n.d.). This finding points to the great inequality in the risk of dying because of an abortion. Women are at an increased risk of acute and chronic abortion complications such as infertility and chronic pelvic pain which can be prevented if every woman has access to legitimate safe abortion when required. The Kenyan High Court ruled that safe abortion care is a fundamental right in a landmark verdict that protects patients and healthcare providers from arbitrary arrests and prosecution (IPPF, 2022). In both counties, oxytocin had a higher availability than misoprostol and calcium gluconate. The availability of misoprostol for safe abortion, PAC, and PPH could avert more maternal deaths than other large-scale interventions in developing countries (Prata et al., 2009). The study findings also reveal that practices do not always reflect adequate implementation of clean delivery practices. Both counties lack clean bedsheets, towels, and sterile code ties. These findings mirror results published by (Moyer et al., 2012) who reported that many recommended clean delivery practices were ignored in Ghana. The results provide an important backdrop against which future interventions can be planned to improve the way infants are handled upon delivery to reduce infections. In addition, there is evidence of disrespect and abuse especially among young mothers. The finding was in line with that of (Bohren et al., 2015) who reported that many women experience disrespect and abuse during childbirth. Disrespect and abuse must, however, be addressed by centering women’s perceptions and needs, both from a human rights perspective and because negative childbirth experiences reduce utilization of health services.Social norms also exacerbate systematic and long-standing inequities in the MCH service utilization, especially in Garissa County. While male involvement in MCH programs has been associated with positive reproductive health outcomes globally (Bawah, 2002) (Terefe & Larson, 1993), few men participate in MCH services. FGDs with the men revealed that they have adequate knowledge of the type of support they ought to give to their partners during pregnancy though they still find their participation to be unnecessary. Thoughtful restructuring of MCH programs to increasingly engage men could strengthen male involvement. Also, an understanding of the dynamics of male influence is therefore crucial in negotiating compromises to improve their involvement in MCH programs (Aborigo et al., 2018). Access to MCH services is also constrained by security concerns especially at night. This may cause travel fares to be significantly higher at night making it harder for women who already found day fare rates as prohibitive to access facilities. Pregnant women are then faced with conundrums on “when”, “where” and “how” to reach hospitals when in an emergency. While the decision-making is a shared activity, the available options vary depending on their socioeconomic status (Banke-Thomas, n.d.). The net result of this is prolonged delays, with many women left alone to find their way or seek the services of a traditional birth attendant which may reverse gains made in improving maternal and neonatal survival. This calls for efforts to be put in place to improve the travel experiences of women through significant road-infrastructural improvements, establishing partnerships with specific taxi companies and behavior change of drivers.A key limitation in this study was selection bias and generalizability. We used a purposive sample from facilities in Nairobi and Garissa Counties. The findings may, therefore, not be representative in the other areas of the country. Nonetheless, this is one of the most comprehensive studies on MCH service delivery involving both clinical and non-clinical providers in different levels of health facilities.

5. Conclusions

- All the facilities visited in Nairobi and Garissa counties have quite a good coverage on MCH services and the population can access to maternal, newborn, and child health services easily. This is an indication that efforts towards scaling up the uptake of MCH services in Kenya are reaping good results. However, the delivery of quality maternal healthcare services was found to likely be impeded by inadequate availability of maternal medicine, compromised space or room for ANC and Neonatal service delivery, inadequate availability of infrastructure and equipment, lack of enough essential medical supplies and cost of associated with maternal and child health services. In the facilities visited in Nairobi and Garissa Counties, there were no sufficiently equipped theaters to handle operations, nor do they have the capacity to conduct any blood transfusion services when they need to. There is a dire need to fulfil the infrastructural, social and logistical challenges in health facilities for increased access, utilization and better MCH outcomes.

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML