-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2022; 12(5): 103-109

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20221205.01

Received: Nov. 1, 2022; Accepted: Nov. 18, 2022; Published: Dec. 6, 2022

Assessment of Hospital Preparedness for Disaster: A Cross-sectional Descriptive Study

Marlon A. Clores

College of Nursing, Ateneo de Naga University, Bagumbayan Sur, Naga City, Bicol Medical Center, Naga City, Camarines Sur, Philippines

Correspondence to: Marlon A. Clores, College of Nursing, Ateneo de Naga University, Bagumbayan Sur, Naga City, Bicol Medical Center, Naga City, Camarines Sur, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

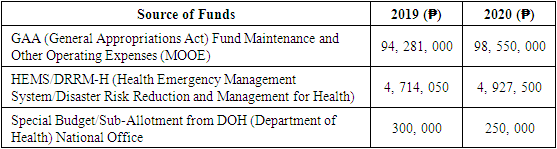

In the Philippines, a Tertiary Level III hospital refers to a tertiary hospital with expensive and sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic facilities for a specific medical problem area. One of the Level III hospitals in the country which operated for more than eight decades is the Bicol Medical Center (BMC), a 500-bed capacity Level III government general teaching/training tertiary hospital under the direct supervision of the Department of Health. However, since its operation, assessment of the hospital’s Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM) is wanting. Using structured interviews, SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) Analysis, coupled with document analysis, the hospital’s capacity, and vulnerability of the hospital to disasters, the protocols, practices, initiatives, and capacity-building of training programs on DRRM for its personnel were analyzed. The hazards, risks, capacity, and vulnerability of the medical center were also assessed. Thirty respondents composed of 10 nurses, 10 nursing attendants, 3 administrative clerks, and 2 administrative aides provided the structured interview data. Secondary data includes records and memoranda. Results showed that the hospital’s DRRM is replete with strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats ranging from its existing communication and new facilities, protocols, plans, and manpower essential for DRRM, however, it is moderately vulnerable to the onslaught of typhoons in the locality, the outbreak of emerging and re-emerging diseases, and the occurrence of fire. Based on the findings, it is recommended based on the DRRM plans, policies, facilities, protocols, budget, and capacity-building programs should be revisited, reviewed, and updated to ensure the resiliency of the hospital to disasters that affect the delivery of health services.

Keywords: Disaster, Disaster Preparedness, Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM)

Cite this paper: Marlon A. Clores, Assessment of Hospital Preparedness for Disaster: A Cross-sectional Descriptive Study, Public Health Research, Vol. 12 No. 5, 2022, pp. 103-109. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20221205.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Coordinated activities and structures for fast and automatic response to limit risks and effects and assessing and evaluating the impact of disaster are essential aspects of preparedness for disasters (Khankeh et al., 2011). Lack of preparedness for disasters results in unexpected impacts on human health and well-being (Sauer et al., 2009), thus, an essential component for disaster management is the readiness and capacities of hospitals to provide health care services during and after disasters (Osman, Shahan, and Jahan 2015, Adini et al. 2012). Disaster readiness of hospitals reflects the preparedness of health systems because as first providers of health services, especially during disasters signify that they can protect the patients, their hospital personnel, and facilities and equipment (Pole, Marcozzo, and Hunt, 2014). Hospitals must be able to manage victims of disasters and other patients needing critical services, including surgeries (Donahue and Fatherstone, 2013). When hospital managers and personnel are knowledgeable and skilled to mitigate the dangers of disasters and enhance their readiness for such unexpected events, the hospital is considered prepared for disasters and emergencies (Sauer et al., 2009; Kearns et al., 2014). In developing countries, the problem with many hospitals is the lack of training, resources, and expertise in disaster preparedness and management (Top, Gider, and Tas, 2010; Mortelmens et al., 2014), resulting in inadequacy or inappropriate response during disasters (Kollek and Cwimm 2011; Djalali et al., 2012). It is therefore important to assess the preparedness of hospitals so that weaknesses, shortcomings, and inadequacies are addressed.Located within the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines is very prone to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The southwest monsoon and low-pressure areas bring heavy rainfalls to many parts of the country resulting in flooding that damaged numerous livelihoods. Furthermore, seasonal warming of the Pacific Ocean, also called the El Niño phenomenon, disrupts the normal weather patterns, and causes droughts in Northern Philippines (Statista Research Department, 2022). At present, the poverty, and the knock-on effects of the Coronavirus Disease – 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, further contribute to the problems that the country is facing: climate change impacts, including sea level rise, increased frequency of extreme weather events, rising temperatures, and heavy rainfall. As a country, the Philippines developed strategies and mitigation measures to address natural hazards and climate change. Disaster management policy has recently become the focus of the national government. In 2010, the Philippine Congress enacted the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (NDRRM) Act to establish a multilevel disaster risk management system and develop resilient infrastructure to allow communities to recover swiftly (Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance, 2021). In 2020, the Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines released Administrative Order No. 2020-0053, Operational Guidelines in the Delivery of Essential Health Service Packages (EHSPs) for Medical and Public and Health Services during Emergencies and Disasters. The guidelines aim to ensure that equitable, accessible, and quality health services and that essential health services are not interrupted even during emergencies and disasters. Despite these developments, there remain many questions about whether hospitals in the Philippines provide health services for saving lives including those that are needed for search and rescue right after disaster strikes, and for preventing and controlling disaster-related morbidities e.g., communicable diseases and vaccine-preventable diseases (DOH, 2020). There is a need to assess the extent to which emergency care and rescue services by hospitals are optimized (Orange Health Consultants, 2021).In this study, a tertiary hospital in the Philippines was examined in terms of the protocols, linkages, practices, initiatives, and capacity-building of training programs on DRRM for its personnel were analyzed. The hazards, risks, capacity, and vulnerability of the hospital were also assessed. As the leading medical health service provider for the entire region where it is located, and the first referral choice during disasters, it is imperative that this tertiary hospital be evaluated so that recommendations for the institution and other similar institutions in the country be formulated.

2. Methods

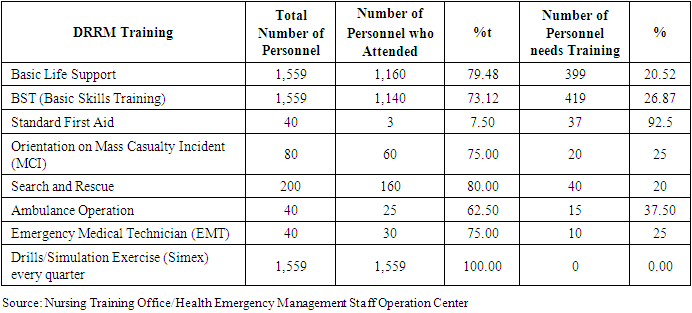

- This was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted in Bicol Medical Center (BMC), one of the tertiary hospitals in the Philippines. The hospital is a 500-bed capacity Level III government general teaching/training tertiary hospital under the direct supervision of the Department of Health. There is a total of 1,559 hospital personnel (410 or 26.29% in the Medical Department, 806 or 51.69% in the Nursing Department, 238 or 15.26% in the Administrative Department, and 105 or 6.73% in the Finance Department) (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. The proportion of personnel in the various departments of the hospital |

3. Results

3.1. Capacity and Vulnerability of the Hospital to Hazards, Risks, and Disasters

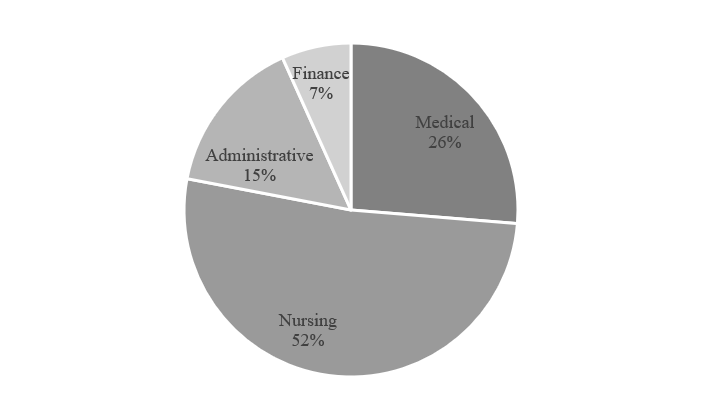

- Records showed that there are more than 800 patients on a typical day at the BMC, hence relatively it is short of around 19.94% of personnel to provide quality patient care, especially during disasters (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Existing and needed hospital personnel |

|

|

3.2. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats to the Hospital’s DRRM

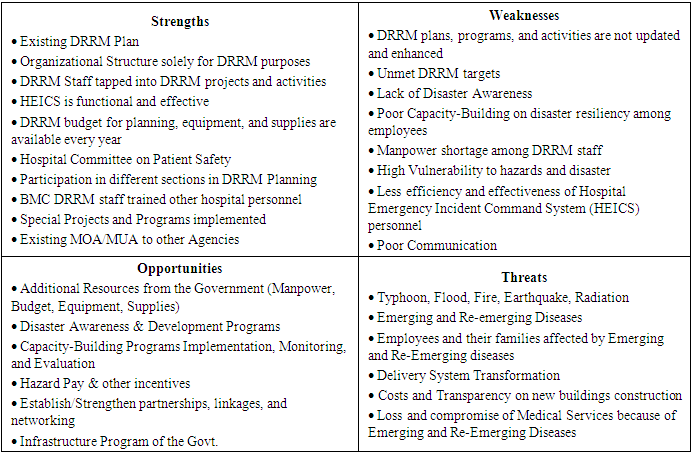

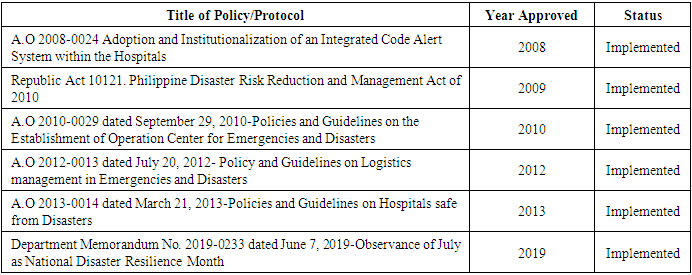

- Table 3 shows the results of the SWOT Analysis of the hospital’s DRRM. The analysis revealed the policies and practices in the hospital which are considered strengths are the DRRM plans which were crafted in accordance with existing government policies and protocols (Table 4). These are implemented and practiced over the years. There is an existing functional organizational structure that is solely for DRRM purposes that are followed by all employees and staff.

|

|

|

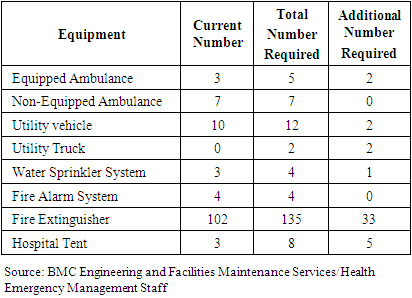

4. Discussion

- The findings of the study revealed the basic issues of the hospital’s DRRM wherein certain causes of the issues were identified. However, there are notable opportunities that outweigh many of the weaknesses giving the impression that the hospital is resilient to disasters. Among the issues and problems which must be addressed include the following: outdated DRRM plans, protocols, and policies, some resources, such as supplies and equipment (e.g., electric generator sets, backup water supply, and telephone lines) are inadequate, lack of knowledge, skills, interest, and active participation of some personnel. Due to these issues and problems being unresolved, many DRRM targets were not met, and the HEIC personnel became inefficient and ineffective. Hospitals should deal with disasters and emergencies at all costs (Sauer et al., 2009), but most hospitals, especially in developing countries (Top, Gider, and Tas, 2010; Djalali et al., 2011) are not prepared for disasters and emergencies due to lack of expertise, training, and resources (Mortelmens et al., 2014) and shortcomings in proper response at the time of disasters (Kollek and Cwin, 2011). The findings of the study is affirmed by this since it was shown that the existing equipment in the tertiary hospital is still found to be inadequate to meet the needs of the patients during emergencies and possible disasters. However, emergency medicines are available in the equipped ambulance which is used during response and there is 100% utilization of medicines in the hospital. Despite this, it was shown also that the hospital personnel, are always ready to respond to whatever hazards or emergencies that could occur in their facilities.In this study, it was the existing equipment, access to the hospital beds, medical facilities, and safety measures in the hospital is still found to be inadequate to meet the needs of the patients during emergencies and possible disasters. Bhadori et al. (2012) and Mulyasari et al. (2013) consider these as functional or nonstructural dimensions of emergency and disaster preparedness. The functional preparedness dimension, in contrast to the human resources dimension and other indicators, is affected by the availability and cost of medical equipment, while the latter is influenced by how the hospital administrators manage human resources and standard trainings (Khamseh et al. 2017). In this study, both the functional and human resources dimensions of the hospital under study need to be improved.The results of the present study support Mulyasari et al. (2013) that structural and non-structural factors, development programs, and training of personnel play a vital role in the preparedness of hospitals for disasters. However, as shown in this current study, building structures of the hospitals that are already old and need retrofitting or restructuring to withstand earthquakes and other calamities need to be prioritized. The same findings affirm Hatami et al. (2017) that the availability of emergency evacuation even in the form of hospital tents is necessary. As the first line of disaster preparedness, hospitals must be assessed and monitored to identify their strengths and weaknesses. This study is an example of how a hospital’s disaster preparedness is assessed, and the opportunities and threats for improvement were also identified. These allowed the researcher to further summarize the gaps and problems that must be addressed. In many countries, like the Philippines, hospitals are the first place to refer victims of disasters and emergencies. The COVID-19 pandemic tested the preparedness of hospitals in the Philippines as hundreds of people got sick and were brought to the hospitals. From January 2020 to September 2022, a total of 3.9 M confirmed cases were reported, with 62,447 deaths (WHO, 2022). SWOT analysis revealed that the threats to the hospital DRRM include intense calamities like the typhoon, floods, fire, earthquakes, and radiation, emerging and re-emerging diseases, the vulnerability of the employees, and their families to infectious diseases, the delivery system transformation, the lack of transparency in the spending for hospital expansion and construction. The interviews and surveys showed that there are important elements at risk due to typhoons, earthquakes, and emerging and re-emerging diseases or outbreaks including personnel, services, building, equipment/medicine supplies, water supplies, and electrical supplies. They fear that if these will happen, work inside the hospital and the delivery of care to patients will be affected. Participants reported that the elements at risk due to typhoons, earthquakes, emerging and re-emerging diseases or outbreaks include personnel, services, building, equipment/medicine supplies, water supplies, and electrical supplies. When these happen, work inside the hospital as well as patients will be affected including employees because of the resulting non-availability of water and electricity. These findings did not differ from what Khan et al. (2021) found in Saudi Arabia in that the most of hospital’s preparedness score indicates an “insufficient” level of preparedness, which is lower than the recommended WHO cut-off level of effective preparedness. While it was found that the weaknesses of the hospital’s DRRM, as perceived by the respondents, include: DRRM plans, programs, activities that need to be updated and enhanced, the unmet DRRM targets, the lack of disaster awareness, poor capacity-building on disaster resiliency among employees, manpower shortage among DRRM staff, high vulnerability against hazards and disaster, less efficiency and effectiveness of HEICS personnel, poor communication and poor sanitation and hygiene, there are many initiatives that had been accomplished. Amongst these are the functioning of the Hospital Committee on Patient Safety and the crafting of the guidelines and protocols to be executed during disasters. Standards are needed to establish consistency, expectations, and patterns for practice. The respondents were also keen and well-meaning when they mentioned that the status of the DRRM of the hospital is the impetus for many opportunities such as additional resources from the government, support for more disaster awareness and development programs, capacity-building programs implementation, monitoring and evaluation, hazard pay and other incentives, establishing or strengthening partnerships, linkages, and networking, and infrastructure program of the government.Based on the findings of the study, it is concluded that the Tertiary Level III hospital in the Philippines which was the focus of the study has a DRRM in place but with the possible magnitude and type of health emergencies and disasters that may ensue, hence the hospital emergency and disaster preparedness should be improved. It is recommended that assessment and monitoring of similar hospitals in the Philippines should be done to design more programs that build a disaster preparedness system for hospitals in the country, hospitals have the capacity to respond effectively to any kind of disaster.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML