-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2022; 12(4): 95-102

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20221204.03

Received: Nov. 5, 2022; Accepted: Nov. 23, 2022; Published: Nov. 28, 2022

Impact of Health Education on Attitude towards Cervical Cancer Screening among Nigerian Pregnant Women in Rivers State

Elechi Elera Lale, Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Ernest I. Achalu

Department of Health Promotion, Environmental and Safety Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Department of Health Promotion, Environmental and Safety Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

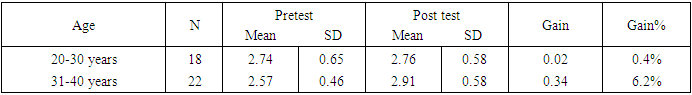

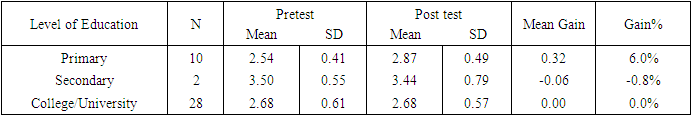

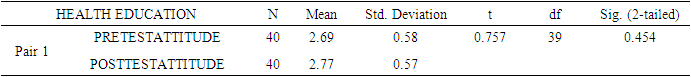

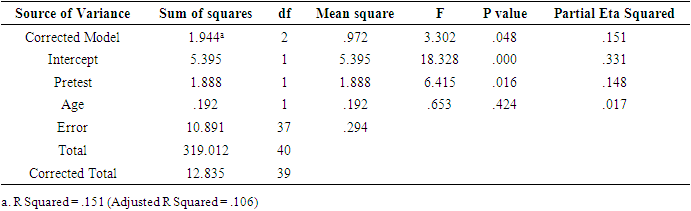

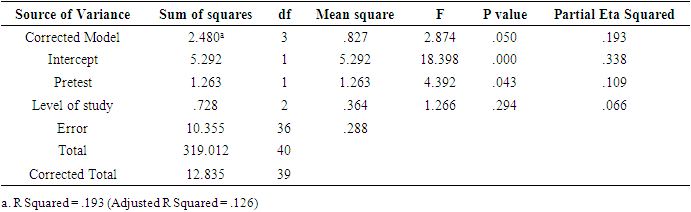

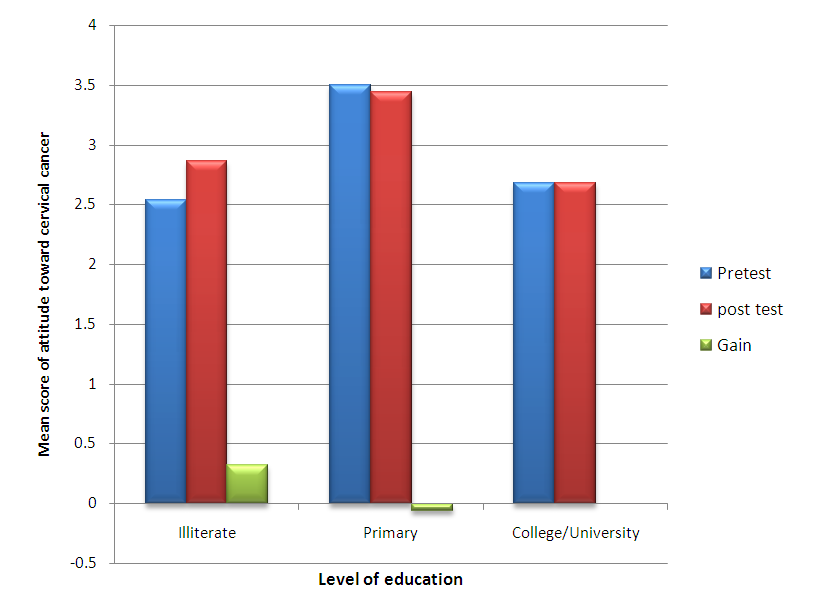

Introduction/Aim: There is need to understand better the attitude of Nigerian women towards cervical cancer screening. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of health education on the attitude of pregnant women in Rivers State, Nigeria towards cervical cancer screening. Materials and Methods: The study adopted a quasi-experimental design. The population for the study was the entire pregnant women in Obio/Akpor Local Government Area of Rivers State. The sample size of forty pregnant women was drawn using the convenience purposive and quota sampling technique. A self-structured questionnaire titled “Effects of Health Education on Attitude towards Cervical Cancer Screening Questionnaire was used to obtain the data from the respondents. The questionnaire was validated by three experts with internal reliability coefficient of 0.80 which was determined using Cronbach Alpha. The data collected were analyzed using mean and standard deviation in answering the research questions, while the null hypotheses were tested at 0.05 level of significance were tested using paired t-tests and ANCOVA. Results: The grand mean score on attitude changed positively from 2.69 before training to 2.77 after training, but was not statistically significant. The pregnant women with college/university education had a higher percentage gain in attitude than their counterparts, but this was not statistically significant. With respect to age, the effect was moderate, which was not significant also. Conclusion/Recommendation: Generally, the health education that the participants received had no significant effect on their attitude towards cervical cancer screening. Therefore, attitude to cervical cancer screening remains a challenge in our environment and this could be due to cultural and religious beliefs that would be worthwhile to investigate in future studies.

Keywords: Impact, Health Education, Attitude, Pregnant Women, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Elechi Elera Lale, Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Ernest I. Achalu, Impact of Health Education on Attitude towards Cervical Cancer Screening among Nigerian Pregnant Women in Rivers State, Public Health Research, Vol. 12 No. 4, 2022, pp. 95-102. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20221204.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Globally, there are nearly 1.5 million cases of cervical cancer clinically recognized, of which eighty five percent of such are found in developing countries, Nigeria being one of such. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer and said to be the fourth leading cause of deaths in women globally that are related to cancer. The incidence of cervical cancer has been reduced by over 70% in the last 50 years in industrialized countries, whereas it is equated that in developing countries, the incidence will rise instead of decreasing, from 444,546 to 588,922 between the years 2012 and 2025 [1]. Cervical cancer is a type of cancer that occurs in the cells of the cervix, which is referred to as the mouth of the uterus. It is the lower part of the uterus that opens into the vaginal canal [2]. Cervical cancer occurs in the tissues of the cervix. It is slow forming in nature and may not have symptoms though can be diagnosed with regular Pap smear [3]. The World Health Organization in 2014 illustrated that a great difference can be seen in the disease occurrence found between women living in developed countries (high-income) and those living in developing countries (low-middle income). They stated that in 2012, 528,000 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed worldwide. These numbers, according to WHO, about 85% which is a large majority occurred in developing countries. In the same year by occurrence, 266,000 women died by cervical cancer globally. Of these deaths, 90 percent occurred in developing countries [4]. WHO in its statement described the main reason for the disparity as the lack of effective prevention, early detection and treatment programs, as well as the lack of equal access to such available programmes. If these interventions are not plugged into, cervical cancer will only be detected at an already advanced stage. At this stage, it will be too late for treatment, poor prognosis and a high mortality rate [5]. The Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) has been identified as a cause of cervical cancer. The HPV serotypes 16 and 18 are responsible for about 70% of the cervical cancer cases globally. They are also known as the high-risk types. There are other risk factors that relate to sexual activity. They include early marriage (below age 20), early age at first sexual intercourse, multiple partners, polygamy, multi-parity, poor knowledge about the disease and long-term use of oral contraceptive pills.The symptoms include bleeding between periods, bleeding after sexual intercourse, bleeding in post-menopausal women, discomfort during sexual intercourse, vaginal discharge with a strong odour, vaginal discharge tinged with blood, pelvic pain and pain during urination [1].Cervical cancer is described as a social disease. Considering the risk factors that are most prevalent in Nigeria, this disease is tailored towards the poor, vulnerable and the less educated. It is estimated that Nigeria loses between 347.4 and 482.7 million US Dollars to cancers each year. This is quite a large sum and can be prevented if widespread and regular screening services are put in place for women who are and have been sexually active. This screening can be done by the HPV test, Pap test or the visual Inspection of the Acetic Acid painted cervix (VIA). Vaccination of women before the onset of sexual activity; be it oral or vaginal, against the HPV which also helps in preventing the disease [1].Cervical cancer screenings are screening tests that are done to prevent cervical cancer and detect abnormal cells in the cervix early. The Pap smear is one of the screening tests that helps in identifying pre-cancerous cell changes in the cervix of the woman. These cells if not identified early and treated can lead to cervical cancers. The other screening test is the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) screening test. This test helps in identifying the virus (human papilloma virus) that brings about the cell changes. In essence, the Pap test involves checking to see if the cells are normal or having some pre-cancerous changes while the HPV test has to do with identifying the virus (HPV) responsible for cervical cancer. Their screening tests can be done singly or together as the case may be. Normal pap smears when done can be repeated after three years. According to the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), a normal HPV test on the other hand can be repeated after five years [6]. When a woman is not sexually active, the best option for her is being vaccinated with the HPV vaccine screening. Screening test in essence is done mainly for women that are sexually active. When a woman is sixty-five years (65) and above, she can opt out of being screened if she has had normal screening test results for several years and has had total hysterectomy done (removal of the uterus including the cervix) for non-cancerous conditions like fibroid. The results of the test can take as long as three weeks before being received. Abnormal test result does not necessarily mean the woman has cervical cancer, since there are many reasons why cells can be abnormal. From Investigations it will be detected if those abnormal cells will eventually become cancerous or not, treatment is given if needed. If results are normal, the chances of developing the disease cervical cancer are slim [6].In Nigeria, research shows that about 40.43 million women are at the risk of developing cervical cancer. Currently, it was estimated that 14,089 women are being diagnosed with cervical cancer every year and out of these diagnosed cases, about 8,240 die from the disease. It is estimated that about 23.7% of women harbor the cervical HPV infection. Also estimates show that the HPV serotypes 16 and 18 are attributed to 90% of invasive cervical cancer. It is projected that in 2025, there will be 17,440 new cervical cancer cases and 10,991 cervical cancer deaths in Nigeria [1]. Nigeria lacks a national population based cervical cancer screening programme. Primary healthcare centres provide health care services to majority of the population. These health care centres are close to the grassroots, easily accessible and affordable. It is very convenient for women of reproductive age to walk in and take up services for their various reproductive needs which include antenatal, maternity, and contraceptive services. In view of these services being rendered, the primary health care centers can serve as cervical cancer screening centre for the population based cervical cancer screening program [7].According to World Health Organization [4], health education is any combination of learning experiences designed to help individuals and communities improve their health by increasing their knowledge or influencing their attitudes. Health education can be defined as the principle by which individuals and groups of people learn to behave in a manner conducive to the promotion, maintenance, or restoration of health [8]. Allport [9] defined attitude as a mental and neutral state of readiness organized through experience, exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related. He believes that individuals have different attitude s towards things in general. It could be religious, politics, sports, fashion, food, etc. He believed that an individual’s attitude describes his/her enduring favourable or unfavourable cognitive evaluation, feeling and actions towards ideas, situations, or objects. In relation to the variables under study, an individual could have an unfavourable attitude towards cervical cancer screening but with health education and increased knowledge, their attitude could become favourable for the better. Attitude reflects an individual’s feelings about a situation or something. One’s attitude predicts sets of responses. In essence, the way an individual responds to a situation can be predicted based on the consistent attitude, be it favourable or not. In relation to the variables under study, health education on cervical cancer screening will bring about a positive or negative attitude from the individual. Statement of the ProblemGlobally, cervical cancer is a major public health problem especially in developing countries like Nigeria. Research has it that about 25,000 new cases of cervical cancer will emerge annually in Nigeria [1]. Cervical cancer can be prevented unlike other cancers, through the prevention of the HPV infection which is even more challenging than most other sexually transmitted infections. This is so because women infected with the HPV virus are generally asymptomatic.Cervical cancer screening is absolutely the most effective tool for the pre-invasive stages of cervical cancer to be detected, since at its early stages it is asymptomatic. The screening creates an opportunity for early detection and prompt treatment before the disease becomes invasive. However, this tool is underutilized and underdeveloped. Some factors are responsible for this, which could be lack of knowledge, negative attitude, cost of service rendered, ignorance, poor performance and inadequate facilities.The researchers reside and work in Obio/Akpor Local Government Area. They observed that the primary health care centres do not offer the service (cervical cancer screening) rather it is done mostly in the secondary and tertiary centers (hospitals). Affordability and accessibility are a challenge for these women since their areas of residence is close to the Primary Health Care Centres. Women that access reproductive health services in the Primary Health Care Centres, which is at the grassroot with a larger population do not have the opportunity. During communication with these women, it was observed that they were ignorant of the term cervical cancer. Since health education has proven to be an effective tool in assisting people gain knowledge and in turn change negative attitudes, the researchers wanted to find out the effect of health education on attitude towards cervical cancer screening in Rivers State.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- A pre-test post-test quasi-experimental design.According to Startton [10], pre-test and posttest research is one of many forms of quasi-experimental design. Three research questions were: (1) What is the effect of health education on attitudes towards cervical cancer screening among the pregnant women? (2) What is the effect of age on attitude towards cervical cancer screening among the pregnant women after health education?(3) What is the effect of the level of education on attitude towards cervical cancer screening among the pregnant women after health education? The three null hypotheses for the study were: (1) Health education would have no significant effect on the attitude of pregnant women towards cervical cancer screening.(2) Age would have no significant effect on the attitude of pregnant women towards cervical cancer screening.(3) Level of education would have no significant effect on the attitude of pregnant women towards cervical cancer screening.

2.2. Study Population

- The population of the study consisted of all the pregnant women in Obio/Akpor Local Government Area of Rivers State. A sample size of forty (40) pregnant women in their second and third trimesters was used for the study. The multistage sampling procedure was used, using the non-probability sampling procedure. The convenience sampling technique was used to select the local government area for the study. These regions have different health centers situated in them; the researcher also used the purposive sampling technique in selecting people who possess the same characteristics needed for the study four health centres were drawn for the study. The researcher further used to quota sampling technique to draw 10 pregnant women from each health centre for the study. A quota was established of 70% women in their third trimester and 30% women in their second trimester.

2.3. Data Analysis

- Data was collected through a self-structured questionnaire of two sections with 14 items tagged Effects of Health Education on Attitude towards Cervical Cancer Screening Questionnaire (EHEATCCSQ). Section A focused on demographic data while section B focused on the variables under study of Strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Disagree (D), Strongly Disagree (SD) for attitude. The instrument was validated by subjecting it to scrutiny of three (3) experts from the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt for face and content validity. Reliability of the instrument was 0.80 using Cronbach Alpha. Data were analyzed using mean, standard deviation for research questions and chi-square, paired t-tests and ANCOVA were used to test the null hypotheses of 0.05 level of significance.

2.4. Ethical Approval for the Study

- The Ethical approval for this study was duly obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee before the commencement of the study.

3. Results

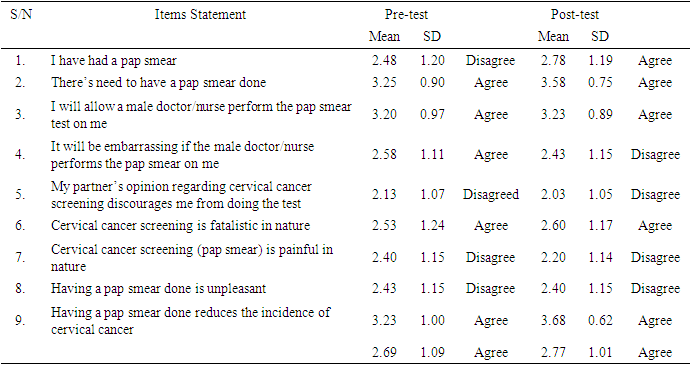

- Table 1 revealed that there was increase in the mean score of the post test for some of the items. The pregnant women agreed that there’s need to have a pap smear done, they will allow a male doctor/nurse perform the pap smear test on me, cervical cancer screening is fatalistic in nature and having a pap smear done reduces the incidence of cervical cancer with posttest mean score of 3.58, 3.23, 2.60 and 3.68. The grand mean of 2.69 and 2.77 for pretest and posttest shows a positive effect of health education on the attitude of pregnant women towards cervical cancer screening in Obio/Akpor Local Government Area.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Bar chart on the attitude of pregnant women towards cervical cancer screening based on age |

| Figure 2. Bar chart on the attitude of pregnant women towards cervical cancer screening based on level of education |

4. Discussion

- In a related study by Weng et al [11], it was reported that only 15 (18.7%) of the participants had had cervical cancer screening before with the reasons for doing so as to know their health status, due to abnormal discharge or as a result of bleeding. In the same study [11] eleven (13.7%) of them believed that screening was not helpful with reasons being that the procedure is uncomfortable, painful, it leads to a low self-esteem, fear of wrong results and the diagnosis of cancer. Barriers citied to cervical cancer screening were; inadequate knowledge, negative attitude towards screening, lack of the screening services and cost of services. Meanwhile, (86.3%, n = 69) in that study [11] believed that screening was helpful with reasons being; for early detection of the disease, to know the health status, to prevent infertility and death. The authors [11] concluded that more education on cervical cancer screening was needed to reduce the misconceptions involved while provision of free services and more participation in education and sensitization from the healthcare providers should be encouraged. The obvious similarity between the Tanzanian study and the present Nigerian study is the need for more health education of the target population. A related study fron Ghana [12] reported statistically significant differences in the pre-post-test scores in the perceived seriousness (t = 3.36, df = 780, p = 0.001) and perceived benefits (t = 9.19, df = 780, p = 0.001) for cervical cancer screening. The study concluded that health education interventions are critical in improving not only knowledge but perceptions, and Increasing self-efficacy of women about cervical cancer and screening.Another related study from Bangladesh [13] reported that, among other factors, access to educational resources affected their increasing awareness of the problem of cervical cancer and eventually their attitude to cervical cancer screening. Their data analysis revealed that women, who are obese, exposed to genital infections and use oral contraceptive drug are at risk for cervical cancer and the risk increases due to their lack of commitment toward screening test. Another related study from Zambia [14] concluded that despite women having adequate knowledge, positive attitudes and perceptions, the number of women who had been screened was still low. However, middle aged and older women, and positive attitudes were found to independently influence women to go for cervical cancer screening. Therefore, attempts should be made to reach women who rarely visit health care services, for example, through increasing health campaigns in partnership with other organizations in the area. In Japanese study, results were based on the Japanese version of the Health Belief Model Scale for Cervical Cancer and the Pap Smear Test (HBMSCCPST), knowledge scores in the categories of Healthy Lifestyles, Cervical Cancer, Cervical Cancer Screening, and screening behavior. Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in cervical cancer screening rates (p = 0.26) between the two groups. However, a small-degree effect size was observed for benefits, seriousness, and susceptibility subscales in both examinees and non-examinees. Although the educational program of this study was effective in improving the knowledge of women in their twenties, there was little improvement in HBMSCCPST and it did not lead to the promotion of cervical cancer screening.Magdalena et al [16] stressed the importance of health education in increasing knowledge which in turn would improve attitude of women towards cervical screening. The study [16] revealed that in as much as the screening was done for the women, they did not want to go ahead to have the test done because of phobia. The few of them who had limited knowledge were encouraged to become health educators so as to help in increasing awareness and improving the attitude of their peers. This could be compared with our present Nigerian study because despite the health education given to the participants, their positive change in attitude towards cervical cancer screening was not a significant one.

5. Conclusions

- 1. Although health education had positive effect on the attitude towards cervical cancer screening among pregnant women in Obio/Akpor Local Government Area of Rivers State, it was not significant. 2. Health education had no significant effect on the attitude of these pregnant women based on their age, as well as with respect to their level of education. However, the women with College/University education had better positive gain in attitude following the health education.

6. Recommendations

- 1. More health education programmes should be employed to positively influence the attitude of women towards cervical cancer screening. 2. Cervical cancer screening should be made available, accessible, and affordable for every woman within the childbearing age. 3. A replication of this study should be carried out in other Local Government Areas of Rivers State and Nigeria as a whole. 4. The workplaces should be targeted for health education to reach women of childbearing age.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML