-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2022; 12(1): 14-23

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20221201.03

Received: Feb. 14, 2022; Accepted: Mar. 4, 2022; Published: Mar. 24, 2022

Implementing a Five Year Non-Communicable Disease Strategic Plan in Kenya: Experience and Lessons

Gladwell K. Gathecha 1, Valerian Mwenda 1, Lilian Mbau 2, Oren Ombiro 1, 3, Ann Nasirumbi 1, Zachary Ndegwa 1, Ephantus Maree 1

1Department of Non-Communicable Diseases, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

2Non Communicable Diseases Alliance of Kenya and Kenya Cardiac Society, Nairobi, Kenya

3PATH Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Valerian Mwenda , Department of Non-Communicable Diseases, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

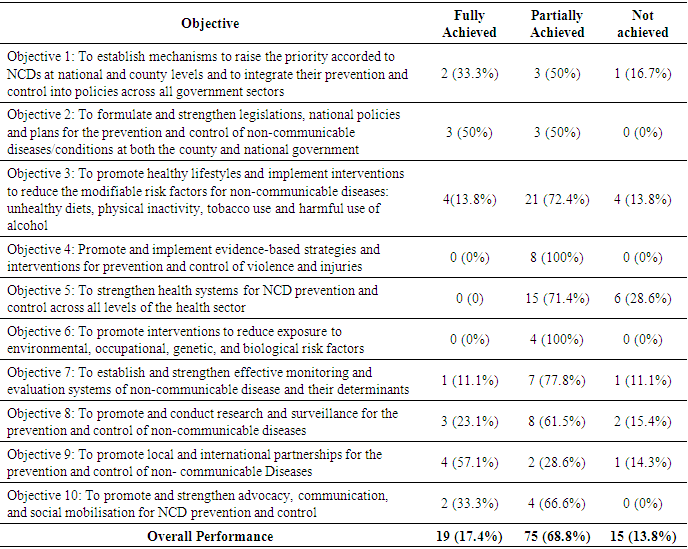

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of deaths globally, with majority of these deaths occurring in low and middle-income countries. Kenya developed its first NCD strategic plan (NSP) in 2015. We present the findings from the final evaluation of the implementation of the NSP. We conducted an outcome evaluation in July-August 2020, using document search and analysis as well as key stakeholder interviews. A thematic review of the documents was done. Implementation of each activity in the NSP was graded into three categories; fully achieved, partially achieved and not achieved. Quantitative frequency analysis was conducted on the proportion of activities falling under each of the three completion status levels. Of the 109 activities in the NSP grouped into 10 objectives, 19 (17.5%) of the activities had been fully achieved, 75 (68.8%) were partially achieved and 15 (13.8%) had not commenced at all. Key achievements include establishment of the NCD intersectoral coordinating committee (NCD-ICC), development of various action plans and clinical guidelines, as well as establishment of NCD surveillance frameworks and development of tools. Major gaps were: insufficient NCD-specific financing both at national and county levels, failure to formulate the identified risk factor mitigation legislations and lack of an effective monitoring and evaluation framework. Health policy formulation and implementation should be linked through an effective implementation framework at the drafting stage. Costing NCD control strategic plans can guide advocacy on adequate financing. Monitoring and evaluation should be prioritized during implementation of NCD strategic plans.

Keywords: Strategic Plan, Non-Communicable Disease, Evaluation, Kenya

Cite this paper: Gladwell K. Gathecha , Valerian Mwenda , Lilian Mbau , Oren Ombiro , Ann Nasirumbi , Zachary Ndegwa , Ephantus Maree , Implementing a Five Year Non-Communicable Disease Strategic Plan in Kenya: Experience and Lessons, Public Health Research, Vol. 12 No. 1, 2022, pp. 14-23. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20221201.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that Non Communicable Diseases (NCDs) kill 41 million people each year representing approximately 71% of all the deaths [1]. Low and middle income countries (LMICs) bear the greatest brunt as 85% of premature deaths from NCDs occur in these regions [1]. The economic burden of NCDs in LMICs is projected to surpass $500 billion per year [2]. In addition, NCDs have a major economic impact on households, due to catastrophic heath expenditure and reduced productivity [3]. In a bid to reduce this rising burden, the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals aimed at reducing by one third premature mortality from NCDs through prevention, screening, treatment and promotion of mental health and well-being [4]. However, studies indicate the majority of the countries especially LMIC will not be able to achieve this target [5]. Investment in NCD control remains low, despite evidence that investment in NCD control can provide a return on investment of $7 for every $1 spent, in terms of increased economic development or reduced health care costs by 2030 [6].NCDs continue to be a growing concern in Kenya responsible for 39% of all the deaths [7]. The risk of premature death due to NCDs in Kenya is estimated at 13% [8]. Cardiovascular (CVD) diseases are the leading cause of death among the NCDs at 46%, Cancer 11%, Diabetes and Chronic respiratory Diseases both at 4% [9]. Beyond the health effects, NCDs also impact the country negatively in the social and economic fronts. It is approximated that 53% of all the Disability adjusted life years (DALYs) occur before the age of 40 years [9]. NCDs have been further demonstrated to result to a 28.6% reduction in household income [9]. During the World Health Assembly in 2013, WHO urged member states to develop National Multisectoral NCD Action Plans by 2015 [10]. Kenya developed its first NCD strategic plan (NSP) in 2015, to cover the period 2015-2020 [11]. The development of the strategic plan was guided by the Non-Communicable Diseases Global action plan (GAP) 2013–2020 [12]. The purpose of the plan was to provide a roadmap towards reducing the preventable mortality and morbidity due to NCDs and improve the quality of lives of Kenyans. The plan envisioned the consolidation of efforts among diverse multi-sector stakeholders to reduce duplication of effort and maximize existing resources. To ensure ownership, the development process was consultative, bringing together various stakeholders including the Ministry of Health, other government agencies, academic and research institutions, the private sector and civil society. The plan had ten strategic objectives which form the basis of the analysis for this paper. While the Kenya NSP was adapted from the GAP, some key differences between the two documents exist. The GAP focused on the four traditional NCDs (cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases) and four traditional risk factors (tobacco use, harmful use of alcohol, physical inactivity and unhealthy diets) while the NSP included other diseases and conditions such as mental health, haemoglobinopathies, injuries and environmental risk factors, in line with the Brazzaville declaration [13]. Monitoring and evaluation is a necessary component of health policy implementation, to measure progress towards attainment of the planned interventions and inform subsequent policy formulation. In order to assess the achievements of the implementation of the NSP, a final evaluation was carried out in 2020; this paper presents the main findings from the evaluation.

2. Methods

2.1. Evaluation Approach

- We conducted an outcome evaluation of the implementation of the NSP. A technical working group (TWG) to conduct the evaluation was formed in July 2020 consisting of officials from the Ministry of Health and Non-Communicable Diseases Alliance of Kenya. A qualitative approach, consisting of document search and stakeholder interviews was used. The TWG formulated the evaluation questions, compiled sources of data and the data collection approaches for the evaluation exercise.

2.2. Data Sources

- The evaluation had three major data sources: a) document search and analysis (policy and clinical guidelines on NCD topics, action plans, disease-specific strategic plans, economic impact evaluations, county integrated development plans, national and county budgets), b) stakeholder interviews (Ministry of Health, County Departments of Health, development partners, and civil society) and c) the NCD navigator platform, a stakeholder mapping tool used to track NCD programs and activities in Kenya. Only documents developed during the life of the NSP (2015-2020) were included. At the national level, personnel in-charge of disease specific and risk factor programs at the Ministry of Health were interviewed, while NCD coordinators at the county provided county-level information. While information on implementing partners was sourced from the NCD navigator platform, telephone interviews were used to supplement available information/seek clarifications where required.

2.3. Data Collection

- An excel-based evaluation tool was developed to collect data on activities that were planned for implementation in the NSP (supplementary files). The evaluation tool had sections for each of the objectives, as well as the activities. For each activity, the activity description, expected output and indicators was pre-populated from the NSP. The respondents were then required to populate the findings and comments sections. The findings were classified into three: those completed as stipulated in the NSP, those partially achieved (implementation on-going at time of evaluation), and those not achieved (implementation not commenced). The comments section captured any explanatory notes on the status of the activity under focus. The data collection took place in two phases, in July and August 2020. The first phase involved conducting a desk document search and review. The County NCD coordinators provided documents required from County governments, such as county specific strategic plans and budgets. The second phase consisted of sending the electronic evaluation tool to national and county officials with instructions on how to populate and submit to the evaluation TWG.

2.4. Data Analysis

- A thematic analysis of the collected documents was conducted, with the objectives of the NSP providing the thematic headings (NCD prioritization, NCD control policies, risk factor control, health systems strengthening, monitoring and evaluation and surveillance and research). Quantitative frequency analysis was conducted on the proportion of activities falling under each of the three completion status levels (Fully achieved, partially achieved and not achieved). The processed data were subjected to technical input from the TWG, focusing on the accuracy and validity of the findings. The findings were then subjected to a wider stakeholder input, as part of the preliminary activities for the drafting of the subsequent NCD strategic plan.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Achievements Towards Objectives

- The NSP had 10 objectives with a total of 109 activities spread across the objectives. At the end of the five years, 19 (17.5%) of the activities had been fully achieved, 75 (68.8%) were partially achieved and 15 (13.8%) had not commenced at all (table 1).

|

3.2. Objective 1

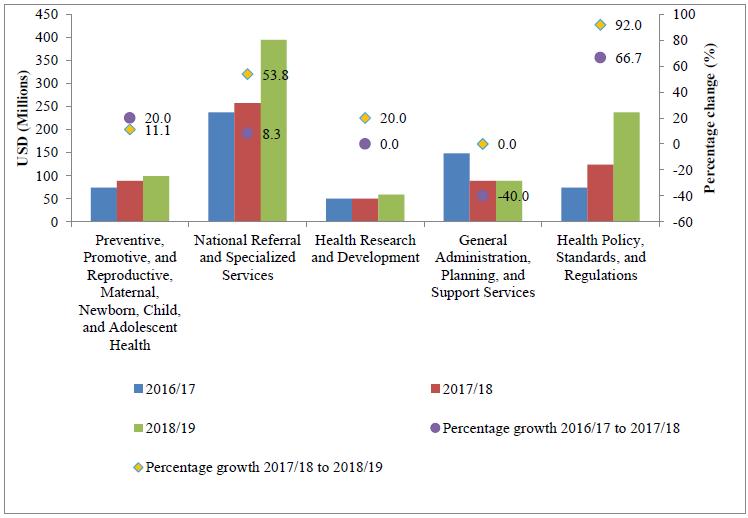

- To establish mechanisms to raise the priority accorded to NCDs at national and county levels and to integrate their prevention and control into policies across all government sectors.Implementation update: This objective aimed at increasing commitment from all players towards prevention and control of NCDs and also strengthening coordination. Under the objective, the country was able to establish an NCD interagency coordinating committee and sensitize all the 47 counties on the NSP. On prioritizing financing for NCD, no gains were realized; in fact, funding for NCD programming decreasing over the period 2015-2020, as assessed by the Ministry of Health annual allocations to the department of NCDs. However, overall increase in financing was noted in general health sectors that play a role in effective NCD control (figure 1). Multisectoral forums were conducted at National level but some sectors such as Agriculture and Interior Coordination have not yet been fully incorporated. In addition, these multisectoral forums have not been established at sub-national (county) level.

| Figure 1. Ministry of Health budget allocation to programmes, FY 2016/2017 to 2018/2019 (source: National and County health budget analysis) [14] |

3.3. Objective 2

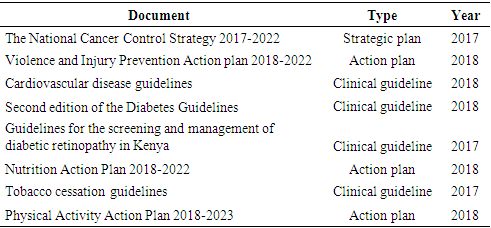

- To formulate and strengthen legislations, national policies and plans for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases/conditions at both the county and national governments.Implementation update: This objective placed the mandate of ensuring appropriate institutional, legal, financial arrangements are put in place by the national and county governments. Strategic plans developed during this period include: the National Cancer Control Strategy, Nutrition Action Plan, Tobacco Control Strategy, Physical Activity Action Plan and Violence and Injury Prevention Action plan (table 2). While no new legislations were developed during the period, the traffic act was amended while amendments to the Cancer Control and Prevention Act 2012 and Mental Health Act are before the legislature. The greatest gap exists in legislations and policies on healthy diet.

|

3.4. Objective 3

- To promote healthy lifestyles and implement interventions to reduce the modifiable risk factors for non-communicable diseases: unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, tobacco use and harmful use of alcohol.Implementation update: Successful initiatives under this objective include incorporation of NCD risk factors in the school curriculum, ratification of the protocol for elimination of illicit tobacco trade as well as conducting mass media campaigns on tobacco control. Public health campaigns were conducted on healthy diets, harmful use of alcohol and physical activity. However, the country was not able to put in place mechanisms for economic incentives to encourage healthy choices for food and beverages, implement community physical activity programs and strengthen the implementation of tobacco product content regulation.

3.5. Objective 4

- To promote and implement evidence-based strategies and interventions for prevention and control of violence and injuries.Implementation update: In line with the Brazzaville declaration of 2011, the strategic plan incorporated reduction of the burden of violence and injuries as one of the objectives. None of the activities under these objectives were fully achieved. Activities that were partially achieved include enhancing public awareness on the risk factors for violence and injuries, strengthening pre-hospital care and improving the organization and planning of trauma care.

3.6. Objective 5

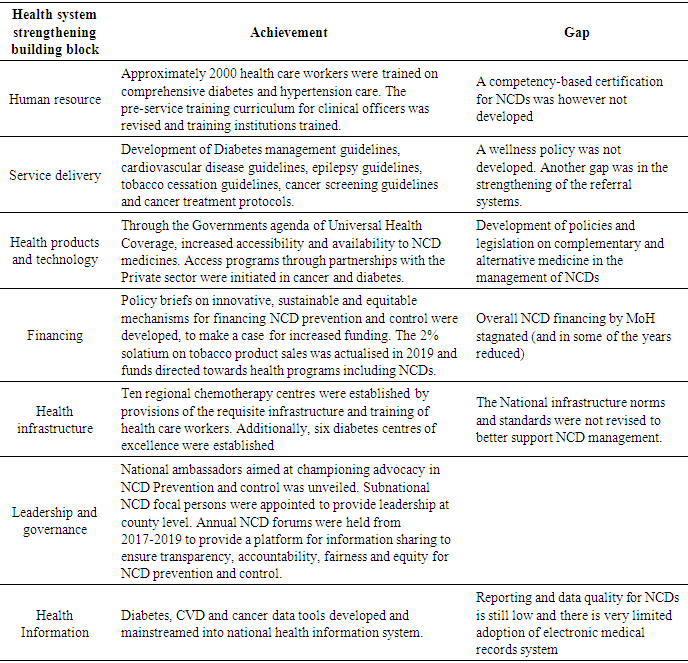

- To strengthen health systems for NCD prevention and control across all levels of the health sector.Implementation update: This objective was intended to ensure strengthening capacity of health systems at primary and secondary levels for screening, early diagnosis and effective management of NCDs. The objective was structured into the health systems building blocks; the achievements per block are shown in table 3.

|

3.7. Objective 6

- To promote interventions to reduce exposure to environmental, occupational, genetic and biological risk factors.Implementation update: The first NCD strategic plan went beyond the four traditional NCD risk factors and incorporated environmental, occupational, genetic and biological risk factors. Implementation of legislations such as the environmental Management and Co-ordination Act, Occupational Safety and Health Act, The Public Health Act, The Health Act was strengthened during this period though it was difficult to measure the extent of enforcement. Human Papilloma Virus vaccination programme was rolled out nationally in 2019.

3.8. Objective 7

- To establish and strengthen effective monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems of non-communicable disease and their determinants.Implementation update: This objective was concerned with establishing effective M&E systems to monitor inputs, processes and outputs; and to evaluate outcomes, trends and impact for NCD programming. The global NCD M&E framework for prevention and control of NCDs was adapted into the Kenya Health Sector Strategic Plan 2018-2023. A cancer registry system was rolled out in ten regions, based at the regional cancer centres. Reporting tools for hypertension, diabetes, cancer screening and treatment were developed and integrated into the national health information system. However, reporting rate remains low, approximately 53%.

3.9. Objective 8

- To promote and conduct research and surveillance for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases.Implementation update: A major milestone achieved under this objective was achieved when the country conducted the first national STEPwise survey for NCD risk factors hence providing the country with key baseline information. A supplement from the survey was published as a special issue in the journal of BMC public health in 2018, with a total of eleven papers. Additionally, NCDs and their risk factors were integrated into existing national household surveys such as TB prevalence survey 2016 and Adolescent health survey 2019. The period also saw various diseases specific studies conducted. Although a national NCD research agenda was not developed, the cancer and cardiovascular control programs developed their respective research agenda.

3.10. Objective 9

- To promote local and international partnerships for the prevention and control of non- communicable diseases.Implementation update: During the period of implementation of the strategic plan, nine technical working groups were established to enhance collaboration with stakeholders; state and non-state, health and non- health. Several programs have incorporated NCD in their health programs, for example TB-Diabetes bi-directional screening, HIV, adolescent and child health. The country also participated in regional and global forums on NCD across the five years. A national NCD steering committee within the Ministry of Health was not established.

3.11. Objective 10

- To promote and strengthen advocacy, communication and social mobilization for NCD prevention and control.Implementation update: This last objective aimed at ensuring efficiency and collaboration in advocacy, communication and social mobilization efforts for NCDs. Health education programs for Persons living with NCDs were successfully implemented through patient support groups. Advocacy forums were held with Counties, the National Health Insurance Fund, Medicines and Supply Agencies and Parliament to strengthen prioritisation of NCDs.

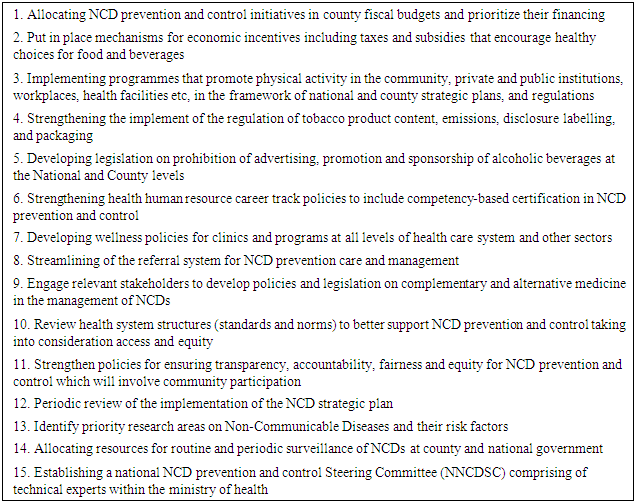

3.12. Activities in the NSP not Implemented at All

- A list of activities whose implementation did not even start is shown in table 4. They range from financing and setting up of various leadership and governance structures to risk factor control strategies. A major gap is lack of periodic review of the implementation of the strategic plan, which offers an opportunity for detecting implementation gaps and executing remedial measures as implementation continues.

|

4. Discussion

- We found that most activities in the NSP were not fully implemented during the period 2015-2020. This is despite Kenya being among the countries recognized to have put in place an operational multisectoral national strategic plan that integrates the major NCDs and their shared risk factors in the WHO Non-communicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2020 [15]. Overall, the country managed to complete one out of every six planned activities; 13.8% of the activities were not done at all. If implemented as planned, strategic plans can enable organizations to achieve their intended goals [16]. The fact that some activities were not implemented shows that certain areas of prevention and control for NCDs remain neglected hence the desired result of reducing the NCD burden could not be fully attained. Efficient implementation of strategic plans has been shown to lead to the reduction of years of life lost (YLL) and years of life lived with disability (YLD) due to NCDs and progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for NCDs [17,18].Low and middle countries such as Kenya are experiencing a double burden of diseases with more emphasis being given to communicable diseases [19]. This was the rationale for the first objective which sought to raise the priority of NCDs at all levels of government. The NCD Intersectoral Coordinating Committee (NCD-ICC), launched in July 2018, brought together technical expertise across all sectors to identify, prioritize and implement cross-cutting interventions in NCD control. This intersectoral body provides a mechanism of drawing in partners outside the health sector. Allocation of funds by national and county levels proved to be a major challenge; in fact, it was noted that allocation to NCD programming by the national government at the national level had been gradually decreasing. There was a 52% decrease in the financial year 2020/21 compared to 2015/16. The decrease could be attributed to the COVID 19 pandemic and the scale up of UHC coverage, which resulted in reallocation of funds. At county level, there was no specific budget item for NCDs hence it was difficult to ascertain how much was allocated to NCDs. Prioritization of NCDs must go hand in hand with increased funding allocation by governments as well as exploration of innovative financing mechanism [20].Although key legislations touching on NCD control were enacted in the years preceding 2015 (the Tobacco Control Act in 2007 and the Cancer Prevention and Control Act in 2012) no new NCD legislation was developed during 2015-2020 [21,22]. The country developed various strategic plans and policies during the period 2015-2020 but the biggest challenge was weak enforcement, monitoring and evaluation. This could be explained by insufficient financial and human resources with the required skills. Lack of resources and data for performing monitoring of policies has hampered the development and implementation of policies in LMICs [23]. Effective enforcement will continue to be elusive in most LMICs due to inadequate capacities for enforcement as well as industry interference [24].The third objective of the NSP sought to domesticate the WHO best buys that aim at reducing modifiable risk factors for NCDs [25]. Close collaboration with the education sector enabled the implementation of the school health policy that saw strengthening of the school curriculum on education on NCD risk factors and also school environment made more responsive towards reducing NCD risk factors [26]. Schools have been identified as important agents of reinforcing positive behaviours at a formative age hence this collaboration should be reinforced [27]. Various community and workplace interventions were also initiated but promotion of physical activity lagged behind. The national physical activity action plan was launched in 2018 but lack of prioritization by stakeholders and inadequate safe spaces may have resulted in lack of progress in implementation. Regarding healthy diets, initiatives undertaken were not scaled-up. Effective partnership with nutrition sector players is responsible for the moderate traction noted in this area. Conversations around mechanisms for economic incentives to encourage healthy food choices commenced in the later phases of the strategy implementation; it is hoped that this will continue in subsequent plans. Kenya has been hailed for its efforts in tobacco control in the region; this is demonstrated by the fact that majority of the tobacco activities in the NSP were accomplished [28,29]. However, lack of adequate capacity and resources hindered the implementation of regulation on tobacco content [30]. This has been compounded further by the entry of new tobacco products such as Lyft into the market [31]. Nevertheless, it has been proposed that efforts should go towards reducing the appeal of all tobacco products rather than ensuring the safety of the contents [32].It was noted that there was no activity fully implementing under the objective aimed at reducing the burden of violence and injuries. The Kenya health policy has placed reducing the burden injuries at the forefront by having this as one of the objectives [33]. Some successes include training on trauma management, research studies on trauma surveillance and care, and developing a violence and injury action plan. Violence and injury programs in many LMICs are not well resourced and lack adequate data. Adequate resourcing of prevention, care and surveillance can reduce the disease burden from violence and injuries [34].Health systems for NCDs have been described as weak and not well documented particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [35]. There was an aspiration to have career track policies to include competency-based certification in NCD prevention and control but this was not achieved. This would have improved human resource for NCDs by ensuring that health care workers have adequate knowledge on NCDs and would be motivated to take up training in NCDs due to expected career opportunities from certification. The country made considerable efforts to develop and implement clinical guidelines which have been found to improve patient outcomes and reduce overall NCD mortality, especially in primary care settings [36]. Under service delivery, streamlining of NCD referral systems remained a challenge albeit having a national referral strategy for all diseases [37]. This may be due to inadequate understanding of the referral structure, lack of awareness on location of referral services and patient factors such as lack of funds and poor health literacy. Weak referral systems for NCDs have been documented elsewhere as major impediment to effective control [38–40].The country’s decision to include risk factors other than the four traditional NCD risk factors was further justified by recent evidence that only 17% of the DALYs from NCDs could be attributed to behavioural and metabolic risk factors [41]. The objective on reducing exposure to environmental, occupational, genetic and biological risk factors required close collaborations with other sectors and effective enforcement of relevant laws. Inter-sectoral collaboration was spearheaded by the NCD ICC. A major milestone achieved in a bid to reduce biological risk factors was the vaccination against HPV, rolled out in October 2019 [42]. However, the uptake of the vaccine has been affected by low levels of knowledge on the vaccines among parents of eligible girls and the disruptions to both the health and education sectors by the COVID-19 Pandemic. The country needs to step up education campaigns to ensure the national targets of HPV vaccination are met.The Country adapted the Global NCD Monitoring and Evaluation framework into the Kenya Health Sector strategic plan 2018-2023 [43]. The main advantage of this alignment was that accountability was now placed at a higher level where the targets were tracked at a Ministerial level rather than at departmental level. A cancer registry system was rolled out in health facilities with cancer chemotherapy centres by provision of requisite infrastructure and training of health care workers and cancer registrars. However, coverage and completeness needs to be improved over time if this registry system is to guide cancer prevention and control in Kenya [44]. The decentralization of cancer services will have the dual advantage of increasing accessibility of cancer services and in making data for decision making more available. A surveillance tool for diabetes and hypertension that was developed will ensure comprehensive data on the two diseases is available (such as number of patients achieving control, complications, medications given and admissions). Health information systems are integral in monitoring a country’s NCD burden and assessing the response to health system interventions [45]. A particular deficiency noted in the NSP was lack of targets in the M/E framework; this made quantitative assessment of achievement of various key result areas difficult. The STEPwise survey conducted in 2015 provided the country with nationally representative data on NCD risk factors [46]. While the county was able to get national data, the survey fell short in providing county/regional level data which is important given that health services in Kenya are decentralised. It is paramount to ensure that the next STEPs survey will provide sub-national estimates. A national NCD research agenda is a useful tool to assist in resource mobilisation and prioritisation of NCD research. By the end of the five-year period, the country had a research agenda for Cancer and CVD only. However, the NCD Research TWG was established in 2020 and was mandated to ensure that a National NCD research agenda is developed.To foster partnership and synergy, nine TWGs were established; Diabetes, CVD, Cancer, Tobacco Control, Violence and Injury prevention, Healthy Ageing, Resource Mobilisation, Research, Monitoring and Evaluation and Supply Chain. However, the efficiency and vibrancy of the TWGs varied with issues such as leadership, partner interest and funding affecting performance. Ineffective partnerships have the overall effect of hampering implementation of NCD plans [47]. In the areas of integration, efforts made include a pilot program for HIV and hypertension integration in Western Kenya and a national program for tuberculosis (TB) and Diabetes bi-directional screening. One of the lessons learnt is that healthcare worker training and follow up and strong monitoring systems are key to successful integration. Within the Ministry of Health there was substantial inclusion of NCDs into other programs activities or policy development. Unfortunately, no formal Ministerial NCD forum was established. Although such a forum would add value to NCD control, capacity creation and interest on NCDs in other disease control programs would provide more public health gains [48].Civil society action was critical during the implementation of the NSP. The NCD Alliance of Kenya (NCDAK) was at the forefront of advocating for strengthening of investment in NCD control [49]. The Alliance was able to bring a united front among persons living with NCDs for the advocacy agenda, hold discussions with parliamentarians and engage in international advocacy meetings. Some of the international advocacy forums resulted in the country benefiting from increased resources in terms of capacity building and financial support for implementation of interventions. During the COVID 19 pandemic, NCDAK was instrumental in agitating for more resources towards NCD care. Having a good working relationship between the government and civil society organisations within the country is beneficial for communication and health promotion [50].

5. Strengths and Limitations

- By documenting the outcome evaluation of the NSP, our work contributes to future NCD policy formulation, both within Kenya and other LMIC. The lessons shared can guide other agencies in evaluating their own implementation journeys. However, this study is subject to some limitations. Reasons for lack of attainment of expected outcomes were not fully exploited. The sub-national picture was obtained from experiences of the County NCD coordinators hence may be less representative. Nevertheless, NCD coordinators are expected to be in touch with the workings of the sub counties and health facilities hence may have the requisite information. The impact indicators could not be evaluated due to lack of data. The country has not able to conduct a second STEPs survey, which would have provided information for comparative assessment of the NSP implementation. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature on lessons learnt in implementing a five-year NCD strategic plan.

6. Conclusions

- The NSP was quite comprehensive but too ambitious given the allocated time and potential sources of funding. It is important for policy makers to realise that there is a close relationship between policy development and implementation; the two should be viewed as an intertwined process. Subsequent strategic plans should have fewer priority areas for the planned cycle, focused and costed interventions, a clear implementation, monitoring and evaluation framework and should strive as much as possible to have political backing from inception.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank all the County Non-Communicable Diseases coordinators and partners who provided information for the evaluation. Additionally, we are grateful to PATH Kenya for providing financial support to conduct the evaluation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML