-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2021; 11(5): 133-140

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20211105.01

Received: Nov. 9, 2021; Accepted: Nov. 24, 2021; Published: Dec. 15, 2021

Impact of COVID-19 on the Utilization of Respiratory and Mental Health Services in Kenya

Njuguna K. David1, Stephen Macharia2, Pepela Wanjala3, Elvis Kirui4, Easter Olwanda5

1Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

2Director (Policy and Planning), Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

3Deputy Director (Health Information), Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

4Medical Statistician, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

5Assistant Coordinator (Costing), Centre for Microbiology Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Njuguna K. David, Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

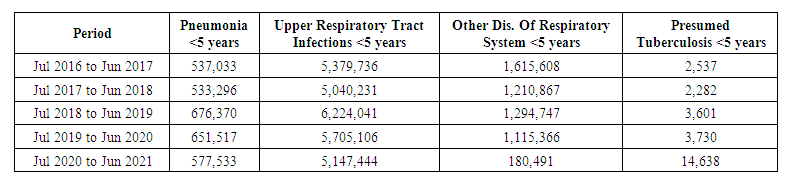

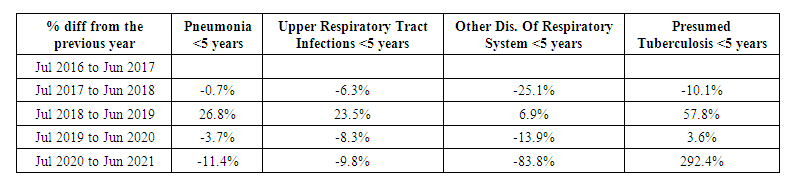

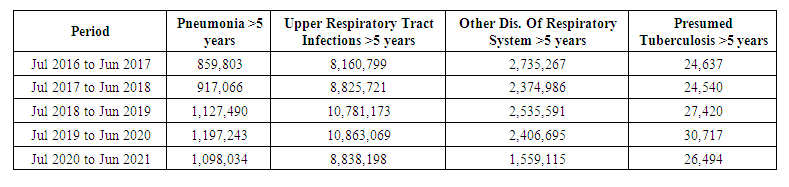

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic may influence the utilization of healthcare services. This study aimed to assess the changes in the utilization of respiratory and mental health services following the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: This was a time series analysis of all COVID patients in Kenya and, patients with respiratory and mental illnesses. We extracted MOH data from health facilities on COVID-19 infections, and outpatient visits for both respiratory and mental health services. Descriptive statistics was used to analyse the utilization trends on Stata version 12. Results: There was reduced utilization of respiratory health services and increased utilization mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the under-fives, there was an 11.36%, 9.77% and 83.82% decrease in the utilization of services for pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections and other diseases of the respiratory system respectively. In contrast, there was a 2-fold increase in the utilization of tuberculosis services. A similar trend was observed in the over-fives with 8.29%, 18.64%, 35.22% and 13.75% decrease in the utilization of pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections, other diseases of the respiratory system and tuberculosis respectively. The majority of the counties in Kenya (38) reported increased utilization of mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Conclusion: The substantial decrease in the utilization of respiratory and mental health services can be attributed to the adaptive measures adopted to deliver health services during the COVID-19 pandemic and the pandemic’s disruption to systems for health and to the health services they sustain.

Keywords: COVID-19, Respiratory illnesses, Mental illnesses, Utilization, Health facility visits and Health system

Cite this paper: Njuguna K. David, Stephen Macharia, Pepela Wanjala, Elvis Kirui, Easter Olwanda, Impact of COVID-19 on the Utilization of Respiratory and Mental Health Services in Kenya, Public Health Research, Vol. 11 No. 5, 2021, pp. 133-140. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20211105.01.

1. Background

- The Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) rapidly spread and affected many countries across the world. The WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) that spread to every corner of the world [1]. The effects of the pandemic included disruptions of social, economic, and political establishments in the World such as government services, global transport, financial and critical health services. It disrupted virtually every aspect of individual, corporate, communal, and global organizations' livelihood [2]. It is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [3], and is characterized by shortness of breath, fever, and pneumonia, which can be fatal in vulnerable individuals. It is transmitted through the inhalation of droplets and interaction with contaminated surfaces. The incubation period of the virus can be up to two weeks with a median of five days during which the virus can be transmitted to others [4]. COVID-19 complications are caused by cytokine release syndrome in which an infection triggers the immune system to flood the bloodstream with inflammatory proteins called cytokines.There is concern that an overlap between the COVID-19 disease and respiratory tract infections could have disastrous consequences. Governments have consistently warned people with respiratory infections that they are at higher risk of severe disease [5]. Upper respiratory tract infections present with self-limiting irritation and swelling of the upper airways with an associated cough. They affect the nose, sinuses, pharynx, larynx, and large airways [6]. Globally, the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections was 17·2 billion in 2019, accounting for 42·82% cases from all the diseases and injuries in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study [7]. Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) occur below the larynx and include pneumonia, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis. Viral lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs), particularly bronchiolitis and pneumonia due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza, are a frequent cause of hospitalisation, morbidity and mortality in children under 5 years of age [8]. In 2016, lower respiratory infections caused 652,572 deaths in under-five children, 1,080,958 deaths in adults above 70 years, and 2,377,697 deaths in people of all ages, globally. Streptococcus pneumoniae was the leading cause of lower respiratory infection morbidity and mortality globally, contributing to more deaths than all other aetiologies combined in 2016 [9]. A recent study focusing on bacterial and viral co-infections in patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to a French ICU reported that 28% of the patients had a respiratory bacterial co-infection upon ICU admission. Most of these co-infections were attributed to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Enterobacteriaceae [10]. Another study reported a 41% rate of co-infection among 17 patients admitted to a North American ICU (11). A rapid review of 9 studies also reported 8% bacterial–fungal co-infection rate in patients with COVID-19 [12]. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic recession have also negatively affected many people’s mental health and created new barriers for those already suffering from mental illnesses and substance use disorders [13,14]. Evidence from a recently developed emotional epidemic curve suggests that without adequate mitigation measures, countries will experience two peaks of negative mental health consequences. The first peak is due to anxiety and corresponds to the peak in COVID-19 cases, while the second peak is due to the negative mental health outcomes such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, suicide, complicated grief bereavement, and relapse of those with existing disorders which corresponds to the post-pandemic period [15]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported the prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. The prevalence of stress in 5 studies with a total sample size of 9074 was 29.6%, the prevalence of anxiety in 17 studies with a sample size of 63,439 was 31.9% while that of depression in 14 studies with a sample size of 44,531 people was 33.7% [16]. Failure to access urgent life-saving treatments for people at risk of respiratory infections and mental illnesses can lead to additional disability and deaths. Moreover, the burden associated with decreases in healthcare utilization may reduce the overall efficacy of a healthcare system. The COVID-19 pandemic has created extensive changes to healthcare systems globally, including large reductions in services, particularly in places hit hard by the pandemic [17]. Being a new disease for which there are still many unknowns, it has also provoked the reluctance to screen and access treatment [18]. It is plausible that lock-downs, quarantine, reorganization of hospital operations, rationing of the medical workforce, and the reluctance of people to seek hospital care led to the decreased healthcare utilization. Reduced or delayed healthcare utilization during the pandemic can have detrimental health consequences that will likely create new challenges for individuals and the healthcare system. There is evidence from other countries that there were variations in healthcare utilization patterns due to COVID-19. In England, there has been a substantial reduction in the weekly admission rates for the acute coronary syndrome [19]. Likewise, Spain and Italy have shown a reduction in admissions and procedures related to myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome [20]. Similarly, another study from Melbourne, Australia reported a significant reduction in emergency department visits when they observed COVID-19 restrictions, including the lockdown. In Croatia, there was a 21% decrease in the total number of admissions across the hospital network during the pandemic in 2020, with the greatest drop occurring in April, when admissions plunged by 51% [21]. The USA reported a 32% decrease in admissions during weeks 11 to 36 in 2020, with significant decreases in admissions for chronic respiratory conditions and non-orthopaedic needs. Moreover, the national lockdown in Thailand was associated with a significant reduction in average daily emergency department visits across traumatic and non-traumatic patients. The average number of daily emergency department visits decreased significantly from 89.1 to 57.0 [22].The emerging threat posed by the Novel Corona virus (2019) pandemic has so far caused devastating social-economic effects both globally and locally and has slowed down all the strategies and plans for the Health sector. The pandemic has exposed the country’s health system weaknesses that needs to be addressed to realize the aspiration of the Constitution and UHC agenda. The first case of COVID-19 in Kenya was announced on 13th March 2020. Response efforts were coordinated through a whole government and multi-agency approach. The National Emergency Response Committee that was constituted provided policy directions on response efforts towards COVID-19 outbreak. The Public Health Emergency Operations Centre was fully activated and continues to coordinate response measures as well as provide daily situation reports to inform planning. Teams of rapid responders and contact tracers were on standby to investigate any alert and follow up on contacts of confirmed cases [23].The government of Kenya also adopted several strategies to respond to the pandemic including, closure of borders, ban on international travel except for cargo, closure of learning institutions, ban on social gatherings, dawn to dusk curfew, closure of religious places, bars and restaurants, and observance of physical distancing. While these interventions yielded positive effects such as slowing down transmission, they also resulted in unintended and undesired health outcomes [24]. Whereas, the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya has been characterized by a high proportion of asymptomatic cases and a lower incidence of severe disease, the changes in healthcare utilization due to COVID-19 in have still not been broadly explored [25]. The potentially severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on utilization of respiratory and mental health services is a critical area of study. Knowledge about utilization disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic is limited, and there remains great interest in understanding utilization disparities for respiratory and mental health illnesses. As such, the objective of this study was to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare utilization for respiratory and mental illnesses and provide insight on the extent to which people are continuing to delay or forgo care nearly one year into the pandemic.

2. Methods

- Study designThis was a time series analysis of all COVID patients in Kenya and patients with respiratory and mental illnesses. The primary indicator was the total number of health facility visits.Data collectionTo evaluate the changes in utilization of both respiratory and mental health services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, we extracted MOH data from health facilities on COVID-19 infections between March 2020 and July 2021. We also extracted health services utilization data for respiratory illnesses between July 2016 and July 2020. In addition, we assessed the changes in the utilization of mental health services between June 2020 and June 2021 as compared to the same period in the preceding year.Data analysisDemographic and clinical characteristics were summarized for the overall population. Descriptive statistics was employed using frequencies, percentages, and diagrams. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Stata version 12 was used to perform the data analysis.

3. Results

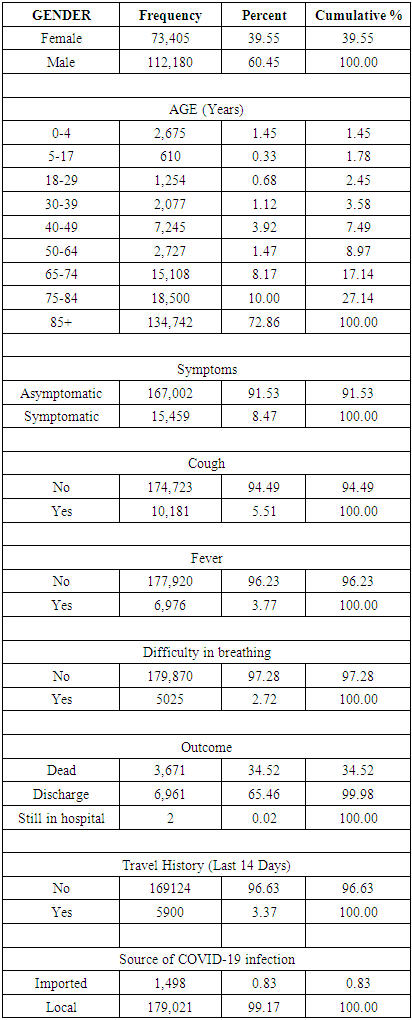

- A total of 185,147 COVID-19 patients were included in this study of which 60.45% were male and 39.55% were female. The mortality rate associated with COVID-19 was 34.52%. Majority of the study participants (91.53%) were asymptomatic. Among the symptomatic, cough (5.51%) was the most common symptom followed by fever (3.77%) and difficulty in breathing (2.72%). Majority (72.86%) of those infected were 85 years old and above. Moreover, 99.17% of the infections were local. Those who had travelled in the past 14 days prior to the infection were 96.63%. See Table 1 below.

|

| Table 2. Trends in utilization of services for respiratory infections in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among under-fives |

| Table 3. Percent difference in utilization of services for respiratory infections in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among under-fives |

| Table 4. Trends in utilization of services for respiratory infections in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among over-fives |

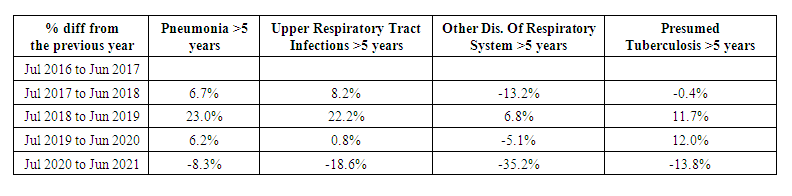

| Table 5. Percent difference utilization of services for respiratory infections in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among over-fives |

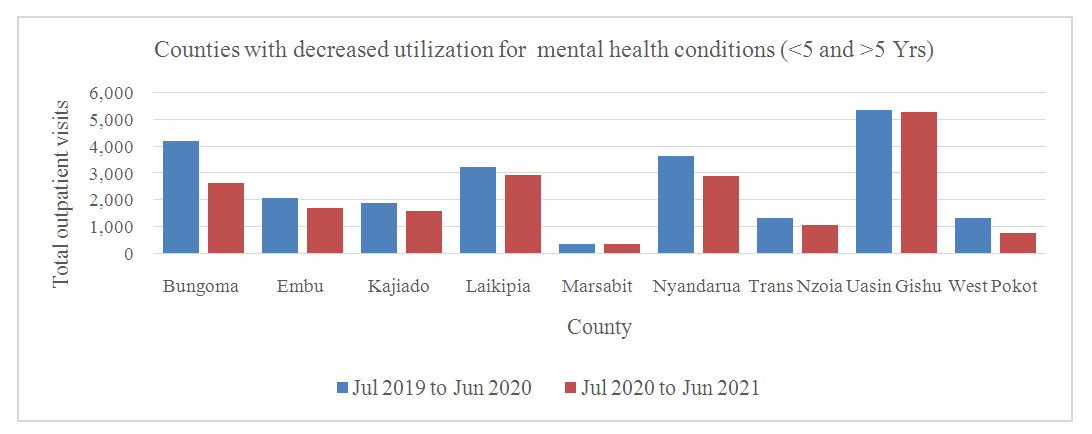

| Figure 1. Decreased utilization in mental health services in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic |

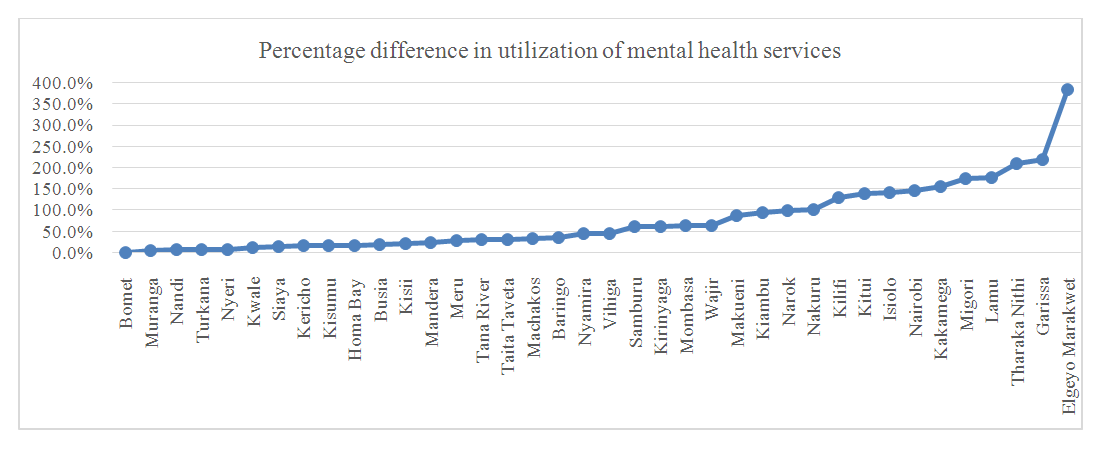

| Figure 2. Percent difference utilization of mental health services in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic |

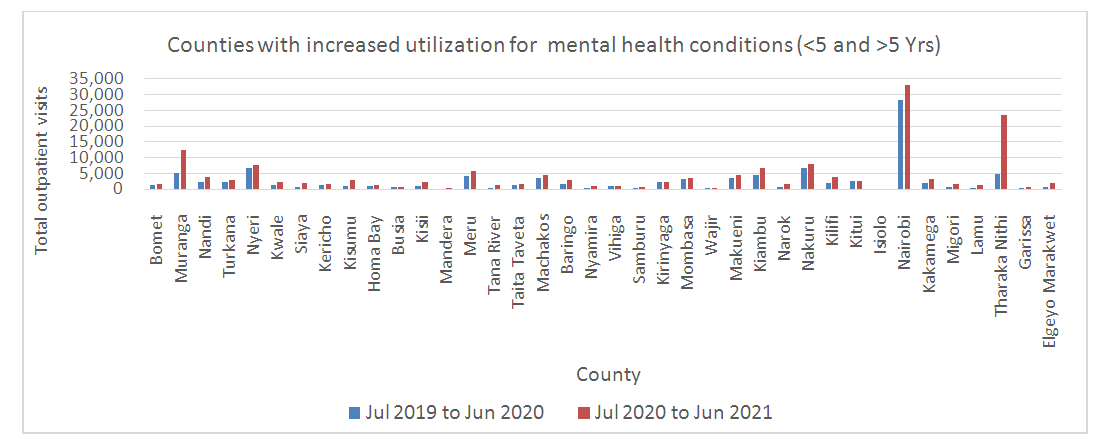

| Figure 3. Increased utilization in mental health services in Kenya before and during the COVID-19 pandemic |

4. Discussion

- The findings of this study support the hypothesis that the COVID-19 pandemic affected utilization of health services in Kenya. Low utilization of healthcare services for respiratory illnesses can be attributed to a number of factors. First, 91.52% of the COVID-19 patients were asymptomatic. The rise in the number of asymptomatic COVID-19 patients in Kenya led to the implementation of a home-based care model to cushion its health system from being overrun by the disease. The Ministry of Health launched the home-based isolation and care guidelines for patients with COVID-19. The guidelines define eligibility, care procedures, medical monitoring, referral system to health facilities, criteria for determining recovery, community participation among others [26]. Second, isolation, social distancing and wearing masks in public areas reduced the incidence and prevalence of respiratory tract infections. These measures can greatly block the transmission routes of respiratory tract virus infections. Two studies attributed the significant decrease in the number of Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic in South America to the prevention and control of the epidemic [27,28]. Likewise, a study in South Korea reported lower positivity rates of the acute respiratory infections caused by seasonal viruses [29]. These findings support the recommendation that personal protective measures such as the use of face masks in community settings in a pandemic era may confer a significant degree of protection.Third, Kenyans shunned hospitals due to fears of contracting the virus from the said institutions. In a bid to ensure patients received quality care amidst the prevailing circumstances, the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council (KMPDC) commenced the issuance of provisional approvals for various registered and licensed health institutions to offer virtual medical services. So far, about 20 health facilities have been approved by KMPDC to provide telemedicine services in the country. Besides, to promote Universal Health Coverage, the KMPDC is now issuing annual licenses to health facilities to offer virtual consultation health services [30]. A similar trend was observed in Yemen where the fear of COVID-19 and fear of being stigmatised are resulted in people in Yemen seeking medical care only when in critical condition. Misinformation and rumours kept people away from hospitals when they were ill [31].Conversely, increased utilization of tuberculosis services for under-fives can be attributed to the adherence to the interim guidance on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tuberculosis is a top ten cause of under-five mortalities and, nearly all these deaths occur in children who are not on tuberculosis treatment [32]. These guidelines directed facilities to give priority to the consultations of high-risk patients including children and people presenting with respiratory illnesses such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [33]. Since COVID-19 and TB have much in common, advances made for COVID-19 can also benefit TB programs.While, majority of the counties in Kenya reported increased utilization of mental health services, the low utilization of mental health services at health facilities can be attributed to the various factors including, the adoption of telemedicine in the delivery of mental health care for persons in isolation and quarantine. Similarly, a rapid review that looked at the utility of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that telemedicine enabled the training of mental health practitioners and allowed them the flexibility to consult patients in distant places without leaving their jobs [34,35]. Likewise, in China, online mental health surveys with communication programs, such as Weibo, WeChat and TikTok allowed mental health professionals and health authorities to provide mental health services online during the COVID-19 pandemic [36]. A study in Australia examined trends in the uptake of telehealth items for mental health during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic and reported that during the peak of the pandemic, there was a 50% reduction in the in-person consultations for mental health and a substantial increase in uptake largely of the telehealth services.Moreover, the low utilization of mental health services in part, can be attributed to the disruption of mental health service provision due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A WHO survey of 130 countries between June and 2020 reported widespread disruption of critical mental health services due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the countries surveyed, 67% experienced disruptions to counselling and psychotherapy services, 65% to critical harm reduction services and 45% to opioid agonist maintenance. More than 35% reported disruptions to emergency interventions for people experiencing prolonged seizures, severe substance use withdrawal syndromes and delirium. Moreover, 30% reported disruptions to access for medications for mental, neurological and substance use disorders [37]. Our findings underscore the need for raising and sustaining awareness regarding the threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic for mental health for all populations [38].In conclusion, there was decreased utilization in respiratory and mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic, partly due to the adaptive measures adopted to deliver health services. On the other hand, it highlights how COVID-19 has been a catalyst for positive change by accelerating new approaches and innovations to improve service delivery and providing an opportunity for synergies in delivering health services. Our study findings also highlight the need for various stakeholders in the health sector to act urgently to mitigate the pandemic’s disruption to systems for health and to the health services they sustain. Moreover, there is a need to increase the preparedness of the health sector to prevent and respond to any potentially infectious diseases’ crisis.The main strength of our study is its originality. To our knowledge, this study was the first to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the utilization of respiratory and mental health services in Kenya. Moreover, we extracted data from all health facilities in Kenya, rendering the results more reflective of the county's status of the utilization of respiratory and mental health services at the facility level.Conversely, there were limitations detected in this study. First, we assessed utilization based on the number of out-patient visits which is a proxy indicator of utilization. Second, while the health service utilization is driven by both demand and supply-side factors, this study only assessed utilization on the supply side. It does not explore the demand-side factors such as existence of demand generation activities and COVID-19 anticipated and enacted stigma from the individual and society.

Conflict of Interest

- The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML