-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2021; 11(4): 111-122

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20211104.01

Received: Sep. 25, 2021; Accepted: Oct. 23, 2021; Published: Oct. 30, 2021

Assessing the Quality of Primary Health Care Services at Basic Health Units in Quetta City, Balochistan, Pakistan

Asif Ali , Sanaullah Panezai

Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan

Correspondence to: Sanaullah Panezai , Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Primary Health Care (PHC) Services are the first level care that are provided to the entire population across the country. Assessing quality of PHC services is important for measuring its impacts on health outcomes of the people, particularly in the capital of Balochistan province where limited is known about the quality of PHC services at Basic Health Units (BHUs) level. Objectives: This study aimed to assess the quality care of PHC services at BHUs level in Quetta city, Balochistan, Pakistan. Methods: The cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study was conducted in February 2019. Out of total 39 BHUs in Quetta, we selected 10 through simple random sampling method. A sample of 400 respondents was selected for the questionnaire survey in the selected BHUs. The Donabedian Conceptual Framework, having three components: structure, process and outcome, was used for assessing the quality of care. Descriptive statistics was used for analysis of data. Moreover, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 23 was used for data analysis and ArcMap was used for making the map of study area. Results: The findings revealed that out of the total respondents, four-fifth (78%) were female users of PHC Services whereas the remaining 22% were males. All (100%) respondents usually visited to BHUs in the case of illnesses. Majority (97.5%) respondents visited BHUs as compare to other health facilities. For structure variables, 50% respondents were strongly agreed about the availability of all equipments, two-fifth (40%) with provision of complete medicines, 64% agreed about the availability of BHU staff. However, 38% were strongly disagreed about availability of dental surgeon. About process variables, 74.5% reported BHU as Usual Source of Care, 58% were strongly disagreed about the availability of obstetric care at BHUs. In the case of outcome variables, around 94.0% were satisfied to strongly stratified with the management of PHC, around three-fourth (77.3%) were strongly agreed about recovery after seeking care at BHUs. Conclusions: This study suggest that policymakers and PHC implementation agencies need to establish strong coordination and put integrated efforts to ensuring the maternal and obstetric care at the BHUs level in Quetta city. Moreover, People’s Primary Health Care Initiative (PPHI) Balochistan needs to ensure the availability of required equipment and human resource as well as basic emergency obstetric care (EmOC) obstetric care at BHUs. Further, the advanced services such as telemedicine, dental services, X-rays, advanced diagnostic laboratories, sufficient stock of medical supplies need to be provided at BHUs in the provincial capital.

Keywords: Primary Health Care, PHC, Basic Health Units, BHUs, Donabedian model, Quality of Care, Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan

Cite this paper: Asif Ali , Sanaullah Panezai , Assessing the Quality of Primary Health Care Services at Basic Health Units in Quetta City, Balochistan, Pakistan, Public Health Research, Vol. 11 No. 4, 2021, pp. 111-122. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20211104.01.

Article Outline

1. Background

- According to declaration of Alma-Ata, Primary Health Care (PHC) means provision of comprehensive, universal, equitable and affordable healthcare services for all countries (Hall & Taylor, 2003). The Alma Ata Declaration was based on recognition that PHC services should be universally accessible including “preventive, curative and rehabilitative” services (Baum, 2007). It has PHC service providers such as vaccinators, lady medical officers (LMOs), male medical officers (MMOs), dispensers, medical technician (MT) etc. (Rasool, 2019). For promotion of PHC services districts have to submit valid information for health policy makers (Zari, 2018). Further, PHC network decreases the rush of people in tertiary care hospitals and can manage the health issues of the people with good health care system at the basic level for the entire population (Agarwal et al., 2017). These services are provided by PHC professionals. (Hastings & Browne, 1978). Moreover, PHC is considered the first stage towards national standard health provision system (Ahamed et al., 2004). PHC services are not sufficient in the world as well as the utilization which is also poor in many states of the world (Almalki et al., 2011). In addition, PHC services consists of primary health assessment, disease prevention, diagnostic needs, and rehabilitative (White, 1994).Institute of medicine defines quality of care as “the degree to which health services for populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001). Quality means degree of performance to improve health within available resources (Khamis & Njau, 2014). The concept of the quality given by health workers is the perfection or expertise in technical field or excellences in health care (Murugan, 2020).In Pakistan, Basic Health Units (BHUs) are the only source for the provision of Primary Health Care (PHC) services. Hence, it is important to know about BHUs, whether these are properly supporting masses for the promotion of their health (Aziz & Hanif, 2016). World Health Organization (WHO) recommends to allocate 6% of the GDP for health sector but Pakistan spends about 2.4% of GDP (World Health Organisation, 2009). Further, Public health expenditure was 0.9% of GDP of Pakistan in 2014-15, which is the lowest in South Asia (Aziz & Hanif, 2016). In past health budget was only 0.23% of (GDP). For sustainable development, there should be a well-organized health system (Aziz & Hanif, 2016). PHC is given by BHUs, Rural Health Centers (RHCs), Maternal and Child Health Centers (MCHCs), TB centers and dispensaries. The number of MCHCs, BHUs and RHCs in Pakistan are 1084, 5798 and 581 respectively (Bashir, 2020). Different studies have used various models for quality assessment in Primary Health Care (PHC) services. Tanahashi Model used by Nambiar et al. (2020) and Naseem et al. (2020). Further, Anderson model used by Natera et al. (2020). Besides that, the Donabedian model is better for quality assessment of PHC services. Structure includes Care providers, qualification of medical staff and infrastructure. Process further includes technical arrangements for treatments and quality of medicines. Outcome refers the recoveries from health facilities (Larson & Muller, 2002). In past, quality improvement was dealing as a way to improve the effectiveness of PHC systems especially in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) (Rezapour et al., 2019). There is contrast in the utilization of the essential services between cities and villages such a study had been conducted in the area of the province Riyadh. There are many evidences about comparing among access and utilization of PHC Services between urban and rural populations of the world. For understanding the barrier and enablers about assessment of PHC services in rural and urban areas of the Riyadh province, KSA (Alfaqeeh et al., 2017). A previous study on availability of PHC services from Peshawar Pakistan has reported that family planning (FP) services were available at PHC centers such as BHUs, however, their availability was just 27% in the sampled three villages. Similarly, only 26% of people had access to medicines in the selected three villages (Mujib-ur-Rehman et al., 2007). In another study from Pakistan, Majrooh et al. (2015) have reported that availability and functionality of the instruments was less at 18% of BHUs. 53% of BHUs had facilities of Antenatal Care services and about 15% BHUs had related medicines available. The availability of medicines was limited in 17% of BHUs (Majrooh et al., 2015). Thus, research studies report that availability of PHC services are insufficient in Pakistan. In the context of Pakistan, studies have reported low quality of PHC services (Hameed et al.; Naseem et al., 2020; Panezai et al., 2020a; Panezai et al., 2020b; Panezai et al., 2017; Panezai et al., 2019). Pakistan has not been able to improve its PHC services to the international level. Presently, there is lack of good quality services in PHC centers at BHUs in Pakistan. Further, there is shortage of quality medicines in BHUs as well in Pakistan (Siddiq et al., 2016). Pakistan’s government is trying to fulfil the moto of the health for all. In addition, the organization such as WHO, UNICEF and World Bank help Pakistan by providing rehabilitative, curative as well as preventive care. In Pakistan, there is the high ratio of the death rates related to communicable diseases such Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) diseases etc. Pakistan is trying to control such diseases by immunization. Mostly, poor and illiterate people visit BHUs in Pakistan while females visit to BHUs are frequent. Thus, the utilization of PHC services at BHUs is much low in Pakistan (Aziz & Hanif, 2016; Hameed et al.; Naseem et al., 2020; Panezai et al., 2020a; Panezai et al., 2020b; Panezai et al., 2017; Panezai et al., 2019).Research studies from Balochistan have showed the low quality of PHC services. In a previous study from Pishin district, Panezai et al. (2017) have reported gender differences in the non-utilization of PHC Services, in which 43.1% women and 51.2% men had not approached Basic Health Units (BHUs) for seeking primary health care. A very important point to be noted the non-utilization of PHC services at BHUs which represented the low quality of PHC services (Panezai et al., 2017). Therefore, there is need to focus on the quality of PHC services in other parts of Balochistan as well. Further, most of the studies on health care reported that improving PHC services are important to improve social well-being. Previous studies have reported low utilization of PHC services in rural areas due to the gaps in the implementation of PHC policies in the province (Panezai et al., 2020b). In the context of Balochistan, majority of previous research studies have focused assessing PHC services in rural areas (Hameed et al.; Naseem et al., 2020; Panezai et al., 2020a; Panezai et al., 2020b; Panezai et al., 2017; Panezai et al., 2019). There is shortage of research that has focused PHC services in urban areas in Balochistan, Pakistan. This rural focus has undermined the comparison of PHC services at BHUs between rural and urban areas. Therefore, to fill the gap in literature, this study aims to assess the quality of PHC services in Quetta city, the provincial capital of Balochistan.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- This is a cross-sectional study. Thus, it has followed a cross-sectional study design for assessing the quality of PHC services at BHUs in Quetta city, Balochistan.

2.2. Setting

- Quetta is the only major city, 10th largest city of Pakistan as well as the capital of the Balochistan province (Bazai & Panezai, 2020). The city in north is bounded by Pishin district, in the south by Masting district, in the east by Harnai and in the west by the neighbouring country Afghanistan (Khan et al., 2020). According to the 2017 Census, the population of Quetta city is about 1,001,205 (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2017). Moreover, the geographical location of Quetta is 30° 11′ N and 67° 00′ E. It has semi -arid climate characterized by low annual rainfall, mostly in western Balochistan. Average temperature of the Quetta district is between 23 to 25 degree centigrade in summer season while in winter season, it is about 4 to 5 degree centigrade (Ahmad et al., 2020). Quetta is divided into two tahsils and one sub -tehsil which are further divided into many wards. Tehsils are Quetta city and Sadar while Punjpai is a sub-tehsil. Most importantly, PHC facilities in Quetta include; rural health centers (RHC), basic health units (BHUs), Civil Dispensaries, Maternal and Child Health (MCH) centers, TB Centers etc.

2.3. Participants

- In the current study, the participants included a sample of 400 women and men who visited the BHUs for seeking PHC services during the survey.

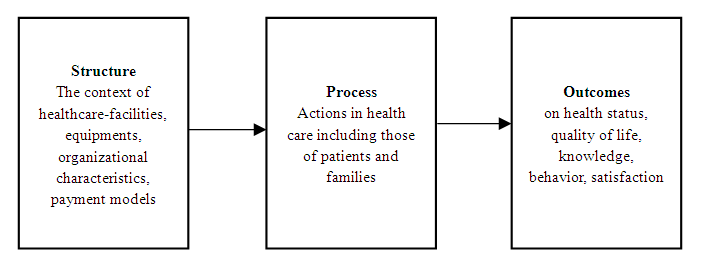

2.4. The Donabedian Model of Quality of Care

- This study used The Donabedian model which is a conceptual model that provides a framework for examining health services and evaluating quality of health care” (McDonald et al., 2011). In this conceptual model care quality is measured by Structure, Process and Outcomes (Donabedian, 1988). The perspective through which care is provided is explained by the Structure in which instruments, staff and physical structure of the hospital are included. The dealings are presented by the Process while the special effects of health care on health status of respondents and population are expressed by the help of the Outcomes (Donabedian, 1988).

| Figure 1. Donabedian Model of Health Care (Donabedian et al., 1982) |

2.5. Variables

- This study has used 5 sets of variables.

2.5.1. Socio-Demographic Variables

- The following socio-demographic variables such as gender, age, language, BHUs, education level, marital status, family type, occupation and economic status were used in current study.

2.5.2. Variables for Utilization

- The variables for utilization included visits to BHU in many health cases such as illness, chronic diseases, Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI), child illness and immunization antenatal and postnatal care, laboratory test, delivery and family planning.

2.5.3. Variables for Structure

- The variables for structure included sanitary condition, seating arrangement, drinking water, availability of all equipment, skilful doctors, compete medicine, medicine for common illness, medicines for Chronic diseases, availability of ambulance, facility for testing Widal etc. Facility for small surgery, medical staff, bathroom, availability of family planning services, availability of labor room, anaemia treatment and were used.

2.5.4. Variables for Process

- The variables for process included well-managed service, visits for USOC, deliveries at BHU, doctors’ behavior, children enrolment, staff is cooperative, ambulance for emergency, waiting time for doctor, confidence PHC services at BHUs, waiting time for lab examination and patients pay for services were used.

2.5.5. Variables for Outcome

- The variables for outcome included family member recovered after BHUs’ treatment, recommending this BHU to others, satisfied about treatment, accuracy of laboratory tests, accurate diagnose, re-visit in case of recovery, doctors’ attention, satisfaction level from BHU staff, satisfaction level from BHU services, provision of quality medicine and overall satisfaction were used.

2.6. Data Sources

- The primary data was collected at each BHU from the women and men respondents. The structured questionnaire was used as a tool for the collection of primary data in the study area. The questionnaire was pre-tested and also modified according to ground realities. The data were collected from respondents in the catchment areas of ten selected BHUs in the month of February 2019.

2.7. Sample Design

- This study intended to assess the PHC Services at the BHUs in Quetta district, Balochistan. A total of 39 BHUs are located in Quetta district for the provision of PHC services. This study selected 10 BHUs by random sampling method through lucky draw method. Later, a sample of 400 respondents was selected for the survey at the selected BHUs. For data collection, each BHU was visited for two days during February to June 2019. The sample of the respondent was selected through the Yamane formula 1967.

| (1) |

2.8. Data Analysis Methods

- Descriptive statistics were used to assess the quality of PHC services at the selected BHUs. Further, ArcGIS 10.2.2 was also used for map generation of Quetta district, Balochistan.

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics of the Participants

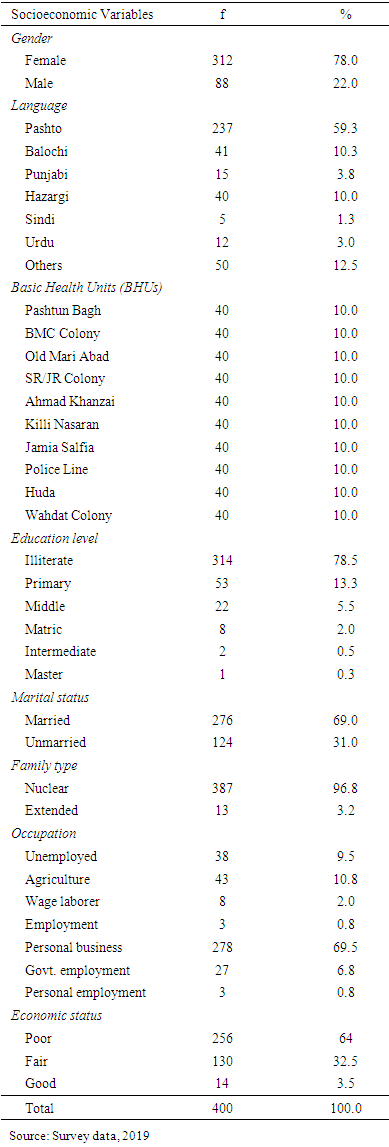

- The results in Table 1 demonstrates socioeconomic characteristics of the participants. The results of the gender group indicates that total respondents were 400, in which almost four-fifth (78%) respondents were female while, one-fifth (22% were males. Female responds were 312 as compare to 88 males. Further in language distribution, Pashto language respondents were three-fifth (59.3%). Other larger languages included Balochi 10.3%, Hazargi 10% and others languages like Brahvi, Persian, Siraki collectively were 12.5%. Other languages included Punjabi, Urdu and Sindhi respondents were in least proportions. As far as education level is concerned, most of the respondents (78.5%) were illiterate. Further, respondents with primary, middle and matriculation level education were 13.3%, 5.5% and 2% respectively. While, intermediate and master level respondents were only 0.5% and 0.3% respectively.

|

3.2. Utilization of the Basic Health Units (BHUs) Services by the Respondents

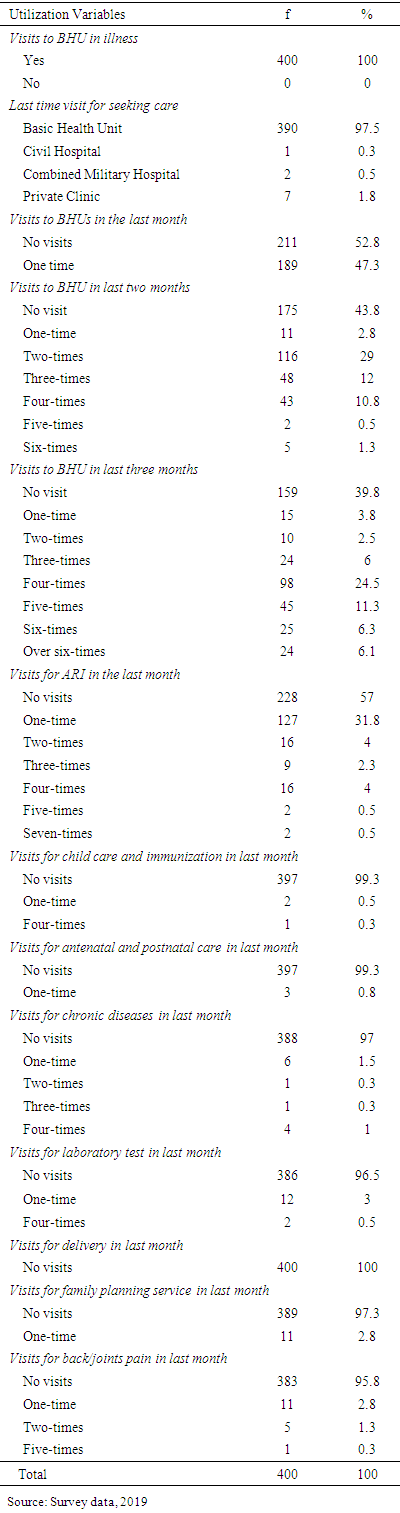

- The results in Table 2 demonstrates the utilization of the PHC services at Basic Health Units (BHUs) by the respondents. All the respondents reported to visit to BHUs in case of illness. Further, almost all the respondents (97.5%) visited BHUs as compared to other health care centers such as private clinics (1.8%), Combined Military Hospital (CMH) (0.5%), Civil Hospital Quetta (0.3%) respectively. Moreover, almost half (52.8%) respondents did not visit any BHU while 47.3% respondents visited BHUs for seeking health care in the last month. Besides that, as far as visits to BHUs in last two months is concerned, 43.8% had not visited at all, 29% visited two times, 12% visited three times and 10.8% visited four times. One-time, six-times and five-times visits were 2.8%, 1.3% and 0.5% respectively.

|

3.3. Structure of the PHC Services

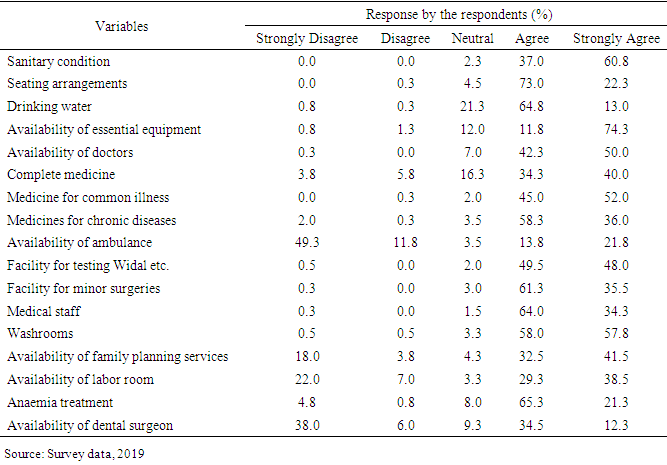

- The results in Table 3 describes the satisfaction of respondents about the structure of the BHUs. The respondents gave different ideas about the cleanness of the BHUs in the study area as most of them (strongly agree: 60.8% and agree: 37%) were satisfied about sanitary conditions. Respondents’ satisfaction with seating arrangement at BHU was also satisfactory with the response rate of agree (64.8%) and strongly agree (13%) while 21% respondents reported to be neutral and only 0.8% reported to be strongly disagreed. Further, respondent’s satisfaction for availability of all equipments in BHU showed that most of the respondents were satisfied with response rate of 74.3% and 11.8% for strongly agree and agree while 12% were neutral in this regard.

|

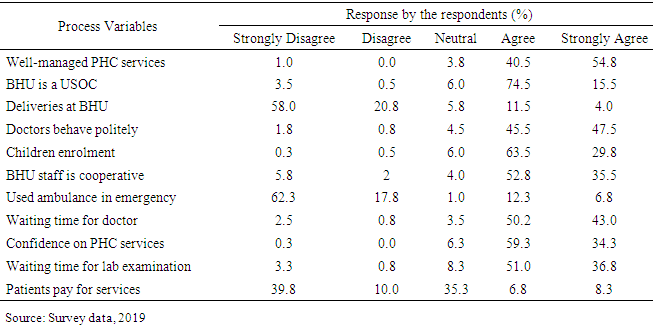

3.4. Process of PHC Services

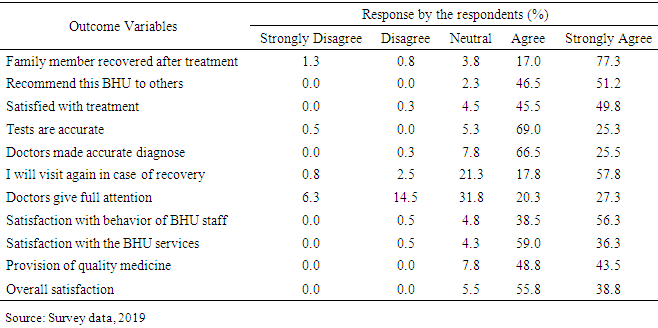

3.5. Outcomes of PHC Services

- The results in Table 5 demonstrates about the response of the respondents about outcome of the PHC services at the BHUs in the study area. As far as satisfaction level for the recovery from BHUs are concerned, respondents were quite satisfied about with the response rate of 77.3% for strongly agree and 17% for agree while 3.8% remained neutral in this regard. Moreover, they also had high rate of response to recommend these BHUs as 51.2% were strongly agree while 46.5% were agree in this regard. Similarly, the respondents were quite well satisfied about treatment at BHU as 49.8% were strongly agree and 45.5% were agree while remaining respondents were neutral in this regard.

|

4. Discussion

- This research was carried out to assess the quality of Primary Health Care (PHC) services at ten selected Basic Health Units (BHUs) in Quetta city, Balochistan, Pakistan. Further, this study used Donabedian model for assessing the utilization, structure (instruments, staff and physical structure of the health facilities), process (delivery of PHC services) and outcome (the effects of health care on health status of respondents) of the Primary Health Care (Donabedian, 1988; Donabedian, 2005). The Donabedian model is a conceptual model that provides a framework for examining health services and evaluating quality of health care and is widely used overall the world” (McDonald et al., 2011). The findings revealed that generally the respondents satisfied with the PHC services at the selected 10 BHUs namely; Pashtun Bagh, BMC Colony, Old Mari Abad, SR/JR Colony, Ahmad Khanzai, Killi Nasaran, Jamia Salfia, Police Line, Huda and Wahdat Colony in Quetta city. Among selected BHUs, the largest one was that located in Wadat Colony and had the most advance facilities including telemedicine services. Similarly, Police Line and Wadat Colony BHUs are the only ones in Quetta that had the facility of X-ray machines. Contrary to these, BHU Jamia Salfia was only the BHU that had poor PHC services having limited physical infrastructure.The findings show all the respondents visited the BHUs for attainment of PHC services which was quite clear from the data that even 97% of them had visited the BHUs in last month. Moreover, quite interestingly, most of the respondents preferred BHUs rather than other sources for health care facilities because the BHUs are very accessible to everyone Out of the total respondents, around four-fifth (78%) were females who visited BHUs for seeking PHC services. The high utilization of PHC services by females is due to the fact that the burden of seeking basic health care for the households, mostly of children is the responsibility of females at households because males mostly go for earning livelihood and work outside of the cities and sometimes even the country. Moreover, female face more health issues compared to men. Hence, rush of the females was the one of the findings of this study, which is a hypothesis of the current study. These findings were quite similar to the findings of Aziz and Hanif (2016) who previously reported that 75.7% of the users of PHC services at BHUs in Pakistan are females. Similarly, a previous study from Pishin District, Balochistan, Pakistan also reported the high utilization of PHC services at BHUs was by females Panezai et al. (2017). Another issue was also reported that peoples from other BHUs catchment areas also created pressure in the some of the BHUs. This problem can be solved by the proper registration mechanism to ensure that public get PHC service in the BHUs where they have been registered. Further, the respondents rarely visited BHUs even for common diseases of Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI), antenatal and postnatal care, chronic diseases and back/joints pain. Further, most of the respondents reported to have attained any Family Planning services as well delivery services from BHUs as well. Moreover, visits for the child vaccination and for medical tests were also too low. These finding were quite similar to the findings of the Panezai et al. (2020b) who also reported non utilization of the PHC services in BHUs even though the study was conducted in the rural areas. Moreover, most of the respondents were illiterate as well as married. Further, the ratio of the young married women was high in selected BHUs thus results mostly were related to the married females. Further, it was also reported that females with poor status had more tendency towards utilization of the PHC services due to their higher health care needs. The current findings are similar with those of Panezai et al. (2020b) who reported that most of users of the PHC services at BHUs level belonged to poor income households. According to Donabedian (1988), structure is a very important indicator in assessment of Primary Health Care (PHC) services at PHC facilities. Similarly, this study had used the structure indicators including PHC services, laboratory and tests, equipment, BHUs staff, availability of medicines, ambulance, professional skills as well as physical infrastructure to assess the PHC services in selected BHUs. These structure indicators are also used by various published studies (Fenny et al., 2014; Getachew et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2018). Similar to the findings of the Majrooh et al., (2015a & b), the respondents were satisfied with the overall sanitary conditions, availability of drinking water as well as seating arrangements in Out-Patient Departments (OPDs). In contrast to the findings of the Majrooh et al. (2015a), 86% people were satisfied about the availability of equipments in BHUs which was quite evident as height and haemoglobin meter were available in the most of BHUs. Moreover, the medicines for common illness were mostly available along with the medical test availability for blood, urine, Malarial Parasite (MP), Widal, pregnancy and diabetes in BHUs. Besides that, the respondents were satisfied with the competence of the doctors along with the availability of the small surgery services in BHUs. In contrast to that, ambulance unavailability was the common issue reported again and again by the respondents as it was a huge concern which made them avoid the BHUs in case of medical emergencies. Moreover, keeping in view the importance of the family planning services, 18% of the respondents were very dissatisfied about the availability of the family planning services which shows the negligence of the competent authorities even in BHUs of urban. Further, unavailability of the dental surgeons was also frequently reported in the BHUs. Overall, the process related variables are based on Donabedian framework for quality health care, which were used in this current study for assessing the quality care was satisfied on the basis of the respondent’s point of view. General speaking, similar to the findings of Fenny et al. (2014) and Ameh et al., (2017) the respondents were quite satisfied with the management, behavior of the doctors and cooperation from staff in BHUs which showed their professional commitment. Further, the respondents also were satisfied about the waiting time for checkup as well as for results after the medical tests which shows that they are being facilitated by the staff. Besides that, having BHU as a Usual Source of Care (USOC) and children enrolment for vaccination was also reported frequently in BHUs. As far as their confidence at BHUs are concerned, they were highly confident at overall services of BHUs. In contrast to overall high satisfaction of the respondents, the rate of having deliveries at BHUs was very low which was quite similar to the study of Panezai et al. (2020a). Further, the use of ambulance in emergency was very low mostly due to the unavailability of ambulance service in most of the BHUs. As far as paying faculty for medicines are concerned, respondents remained indecisive as 39.8% strongly disagreed to pay anything while 35% remained neutral which shows that they might have been paying in some cases.The outcome related variables based on Donabedian framework for assessing the quality health care were measured on satisfaction level of the respondents in this study. Generally, respondents were much satisfied about the outcomes of PHC services at BHUs. Similar to the findings of Aziz and Hanif (2016) respondents were satisfied from the treatment services and the response staff at the BHUs. Moreover, the respondents were also satisfied with the quality of tests, accurate diagnosis, quality medicine availability and reported to have high rate of recovery from BHUs.it as explained earlier, mostly poor visited BHUs, thus they continue visiting until they got fully recovered. Further, in case of recovery, they were also quite satisfied and reported willingness to revisit as well as strongly recommending the BHUs to other for medical facilities which were similar to the findings of the Gangai (2015). Apart from overall high level of satisfaction, the respondents in some cases, however, were not quite decisive about the level of attention given by the doctors where half the respondents were either neutral or dissatisfied. It is the common problem in the study area where patients always lament about the rude behavior and less attention to the patients.

5. Conclusions

- The findings of this study showed that quality Primary Health Care (PHC) services are available at Basic Health Units (BHUs) in Quetta district, the provincial capital of Balochistan province, Pakistan. The findings imply that the BHUs in urban Balochistan are better-managed to provide comparatively better-quality PHC services to its catchment population. As Quetta is most urbanized region of the province, the overall conditions of the BHUs services are better compared to rural areas of the region. Each BHU had high level of satisfaction on the basis of the components of Donabedian Quality of Care Framework: structure, process and outcome, except a few indicators. The structure variables which were almost satisfied on the response of the respondents included availability of all equipments, medicines availability, different minor medical tests facilities, accurate diagnosis and treatment, cooperative and polite behavior, availability of medical officers, female medical technicians (FMTs), lady health visitors (LHVs), while the variable of availability of family planning services and labor room reported bit of dissatisfaction as well. On the other hand, few indicators were not satisfied such as conducting child deliveries, availability of ambulance in case of medical emergencies and dental surgeon is BHUs. Moreover, respondents also reported the doctors’ behavior not giving proper attention in some BHUs. Even though findings show overall high level of satisfaction with PHC Services, the dissatisfied indicators can’t be neglected as low rates of child deliveries and unavailability of ambulance in case of the emergencies at the BHUs can cause much of trouble for the patients visiting BHUs for seeking emergency care. Therefore, it is suggested to policymakers and the competent authorities such as People’s Primary Health Care Initiative (PPHI) Balochistan, the Provincial Health Department and District Health Officer (DHO) Quetta to establish strong coordination and put integrated efforts to ensuring the maternal and obstetric care at the BHUs level in Quetta city. It is direly needed to ensure the availability of basic equipment, sufficient medicine and the availability of lady doctors at the BHUs to insure the child deliveries in each BHUs. Moreover, the BHUs should be provided the stand by ambulance services at the BHUs so that medical emergencies including basic emergency obstetric care (EmOC) services are provided to save lives in case of emergencies. Further, the advanced services such as telemedicine, dental services, X-rays, advanced diagnostic laboratories, sufficient stock of medical supplies need to be provided in the remaining BHUs of the provincial capital in order to reduce the pressure of patients on tertiary care hospitals in the city.

Limitations

- The current study has been conducted in the urban area, the Quetta city of Balochistan province. Therefore, its findings may not represent the poor performing BHUs in rural areas. Moreover, the conclusions cannot be generalized to the PHC services at rural areas, as urban areas may have a better degree of satisfaction in contrast to rural areas which have lowest degree of satisfaction as far as PHC services are concerned.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML