-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2021; 11(3): 90-98

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20211103.02

Received: Sep. 29, 2021; Accepted: Oct. 18, 2021; Published: Oct. 30, 2021

Prevalence of Blood Donors and Significant Factors Affecting Blood Donation within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal During the Pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 Period

John Raphael M. Basilio, Arriane Jzayne S. Awatin, Krishia Anne C. Bagsit, Florydayne M. Capio, Fe Frances A. Fajardo, Erika Marie A. Gamutan, Karl Daniel E. Ronquillo, Ma. Gina M. Sadang, Julius Eleazar D. C. Jose, Roberto M. Manaois

Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Correspondence to: John Raphael M. Basilio, Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Maintaining a safe and reliable blood reserve plays an indispensable role in patient care. Primarily acquired through voluntary blood donations, blood products are used for treatment of various medical conditions and in critical circumstances. Even in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for donated blood is perennial. On this account, this study sought to compare and determine any changes in the number of blood donors in all blood centers in the National Capital Region (NCR), Bulacan, and East Rizal before and during the persisting pandemic, and to determine the extent at which the factors significantly affect the donors’ intention to donate blood. Statistical data was obtained from the Philippine Red Cross (PRC) to determine the number of blood donors recorded in 2019 and 2020. Supplementarily, using the snowball sampling method, the researchers disseminated an online survey via Google Forms consisting of multiple choice and 4-point Likert scale questions. The 141 valid responses obtained were then analyzed through descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation, and 2-tailed T-test with the aid of IBM SPSS Statistics. Results showed a 59.5% drop in the total number of blood donors from 2019 to 2020 and 48.9% decline among the study participants. Based on the responses, particular motivational beliefs are shown to influence the participants’ intention to donate blood. In this time of crisis, managing the blood supply can be achieved by understanding the effects of the pandemic to the blood donors themselves along with their underlying factors. Actions fitting to address these factors must therefore be considered.

Keywords: Blood donation, Blood donors, COVID-19, Factors

Cite this paper: John Raphael M. Basilio, Arriane Jzayne S. Awatin, Krishia Anne C. Bagsit, Florydayne M. Capio, Fe Frances A. Fajardo, Erika Marie A. Gamutan, Karl Daniel E. Ronquillo, Ma. Gina M. Sadang, Julius Eleazar D. C. Jose, Roberto M. Manaois, Prevalence of Blood Donors and Significant Factors Affecting Blood Donation within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal During the Pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 Period, Public Health Research, Vol. 11 No. 3, 2021, pp. 90-98. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20211103.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Blood donation is a medical intervention where a donor transfuses blood to a recipient. It is commonly done by inserting a needle (usually 16 or 18G bore) in a vein within the antecubital fossa, although other more prominent veins are also used. It is an essential life-saving procedure which helps treat patients who are in need of blood products, indicated for purposes of transfusion due to anemia, acute blood loss, hereditary hemochromatosis, myeloproliferative disorders such as polycythemia and porphyria, and in preparation for surgical procedures [1]. Indubitably, blood donation plays a vital role in healthcare provision worldwide. Beyond the multitude of clinical significance of blood donation to its recipients, the procedure also turns to the donor’s advantage in several aspects. It helps the donor by revealing potential health problems and by reducing harmful iron stores which contribute to diseases such as heart attacks, strokes, and cancer [2]. More so, regular blood donors may have less risk for cardiovascular disease due to having lower mean total cholesterol [3]. However, while donating blood has been shown to have a myriad of benefits, not all people are as eager to donate blood as some see this action as being impersonal compared to other voluntary activities. There is also a chance of deferral even if the donor wants to donate due to an existing medical condition, which may compromise the donor and recipient [4]. Other factors include fear (fear of needles, contracting HIV, or finding out that they had an infection), inconvenience, and lack of awareness [5]. Complications such as pain, discomfort, allergy, hematoma, vasovagal reaction, and arm-related injuries subsequent to blood donation can also put blood donors in an unfavorable position [6].In the Philippine context, the Committee on National Blood Service Program–composed of the Department of Health (DOH), the Philippine Red Cross (PRC), and the Philippine Blood Coordinating Council (PBCC)–work hand in hand to provide an adequate supply of safe blood for transfusion to serve the major blood demands of the country [7]. Since the creation of the National Voluntary Blood Services Program, the government health sector has made efforts to promote voluntary blood donation. Unfortunately, with the current Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the country faces a presumed hurdle with its goal of sustaining the number of blood donors and donations. With blood supply having a vital role in healthcare provision, any changes in the number of blood donors may bring adverse consequences to the delivery of healthcare service. For this reason, this study intends to compare the number of blood donors within the areas of National Capital Region (NCR), Bulacan, and East Rizal before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and determine the factors that affect the intention of blood donors to donate, i.e.: the motivational and inhibitory behavioral, normative, and control beliefs.

1.1. Objectives of the Study

1.1.1. General Objective

- The study aims to compare and determine any changes in the number of blood donors in all blood centers within the National Capital Region (NCR), Bulacan, and East Rizal before and during the persisting pandemic, and to determine the extent at which the factors significantly affect the donors’ intention to donate blood.

1.1.2. Specific Objectives

- This research specifically pursues to:1. Determine the number of blood donors in all blood centers within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal before and during the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2019 to December 2020;2. Determine if the factors in the behavioral beliefs affect the donors’ intention to donate blood; 3. Determine if the factors in the normative beliefs affect the donors’ intention to donate blood; and4. Determine if the factors in the control beliefs affect the donors’ intention to donate blood.

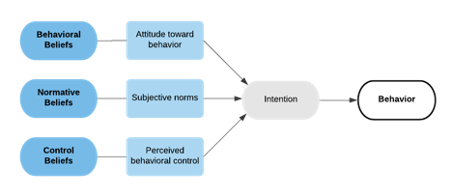

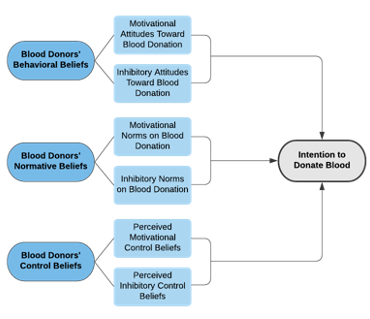

1.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

- The theory of planned behavior (TPB) assesses an individual’s attitude or eagerness to do a specific behavior. Developed by Icek Ajzen [8], TPB explains the relationship between intentions and actions - examining how behavior is guided by one’s objectives and plans, and discerning factors which may have inhibited an individual from executing the said action. This theory consists of three considerations, namely: behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs.Behavioral beliefs refer to beliefs about the consequences of a certain behavior. This yields to either a favorable or unfavorable attitude towards the behavior, wherein an individual assesses the outcome based on his personal beliefs prior to its actual execution. Normative beliefs, on the other hand, are based upon one’s perceived expectations of authority figures/groups. Substantially, this implies that an individual’s motivation is influenced by the behaviors displayed by the society, implicating that he is more likely to perform a behavior he perceives to be appropriate based on what is common in the group [9]. Normative beliefs, therefore, result in social pressure on whether to perform a behavior or not. Meanwhile, control beliefs are drawn from the existence of factors which may influence the ease or difficulty of performing a certain behavior. These beliefs are based on an individual’s perception of the extent of control he has over his own behavior. As a rule, if the individual deems the behavior’s outcome to be favorable, there exists a social pressure to perform the behavior, and the action appears to be within his control, the stronger the individual's intention becomes–ultimately leading to his involvement in the said behavior.

| Figure 1. Theory of Planned Behavior [8] |

| Figure 2. Operational Framework Adopted from the Theory of Planned Behavior [8] |

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

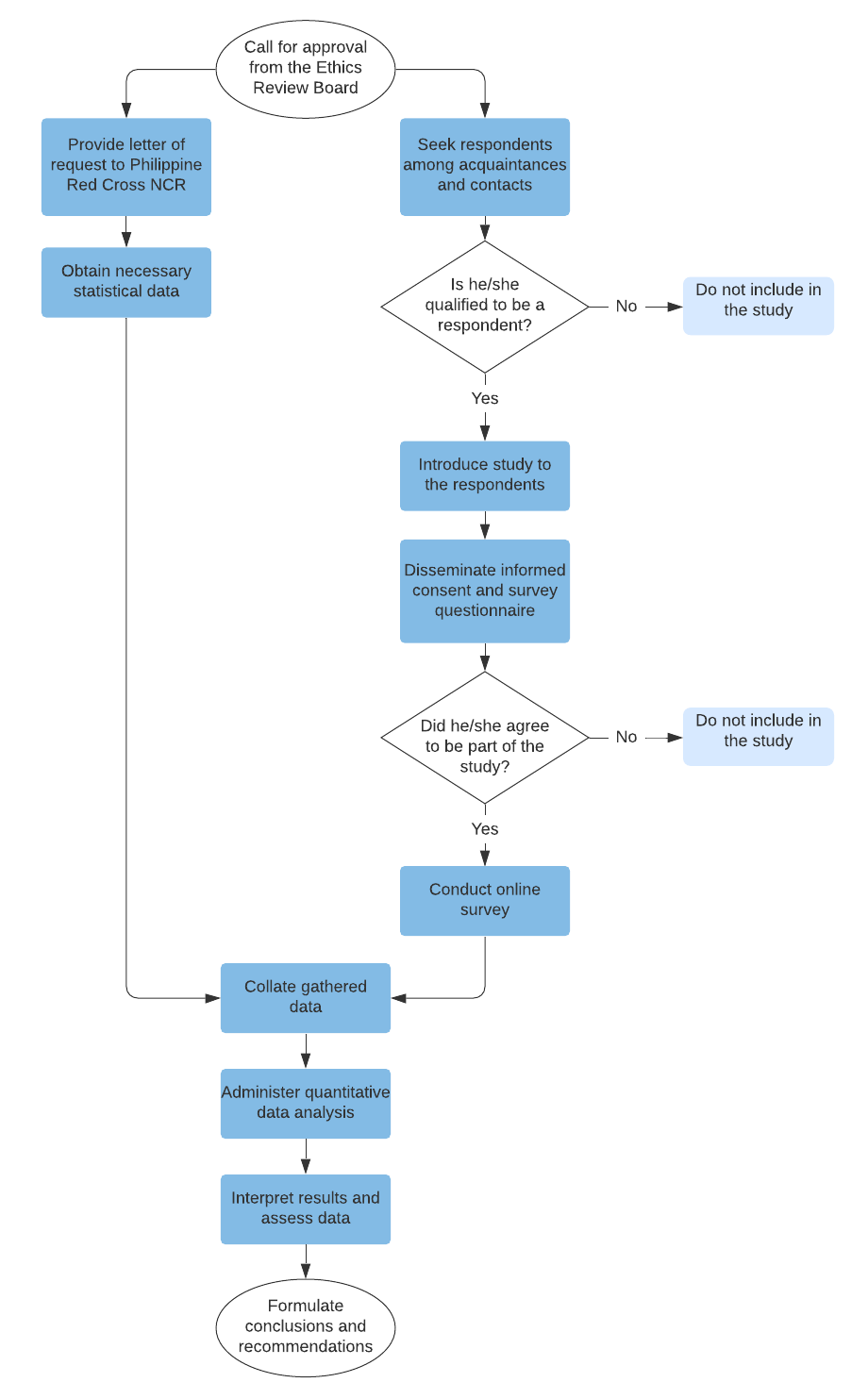

- The study is a descriptive correlation study. To determine any changes in the number of blood donors in any blood centers within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, necessary statistical data were obtained from the Philippine Red Cross (PRC) NCR. Subsequently, a survey questionnaire was distributed via Facebook, Messenger, and email among potential respondents. The said respondents must be blood donors who are at least 18 years old and have successfully donated blood in any blood centers within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal between 2019 and 2020. Based on the data provided by the PRC, the study has targeted approximately 130 respondents, representative of a population size of 5670 blood donors. This sample size falls under a confidence interval of 95% with 8.5% margin of error, calculated from a 2-year population of 136,090 blood donors in 2019 and 2020.

2.2. Instrumentation

- The study utilized a survey questionnaire curated to evaluate the number of blood donors before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and the significant factors behind the donors’ willingness and reluctance to donate, in order to supplement the statistical data gathered. This instrument utilized the Likert scale with the following factors towards one’s decision to donate blood incorporated in the questions: behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs and control beliefs. The questions used in this study were modified from Schnaubelt [10] in accordance with the COVID-19 pandemic. Through snowball sampling, the instrument was disseminated to the respondents via Google Forms.

2.3. Diagrammatic Workflow

2.4. Ethical Considerations

- Prior to conducting the study, the researchers have sought approval from the University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Pharmacy Research Ethics Committee. The respondents have the autonomy to participate in the study through the provision of an informed consent prior to answering the survey, explaining the benefits, objectives, and limitations of the study. The researchers also declared a statement of confidentiality in the said consent, ensuring the respondents that the information gathered shall solely be used for research purposes, with their identities kept confidential and anonymous. No monetary compensations/reimbursements/ entitlements were given to the respondents. Furthermore, the respondents were allowed to withdraw anytime from the study without any prejudice.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics was used for this study, particularly in summarizing the participants’ demographic profile and interpreting the results of the survey tool via weighted mean. This study also utilized Pearson correlation and 2-tailed T-test to determine the relationship and degree of correlation, respectively, between the different variables such as the factors that inhibit one from donating blood before and during the pandemic, and the factors which may motivate one from donating blood before and amid the pandemic. Results were analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics, wherein p-values <0.05 were considered significant while p-values <0.001 were considered highly significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile of Participants in the Study

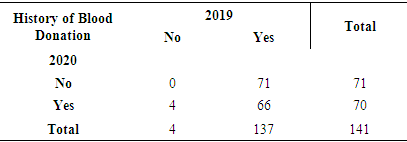

- At the end of the data collection period, a total of 243 participants agreed to answer the online survey. Out of the total, only 141 (58.0%) were found to have donated blood between 2019 and 2020 in NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal. This is 8.5% greater than the calculated sample size of 130 at 95% confidence interval with 8.5% margin of error.The average age of the participants in the study was 24.3(± 6.6) years. In terms of biological sex, there were more females (56.0%) than males (44.0%). In terms of history of blood donation, there were more participants who donated blood in 2019 (97.2%) than in 2020, with 66 (46.8%) of the participants who have donated in both years while 4 (2.8%) donated in 2020.

3.2. Decline in the Number of Blood Donors

- Among the 141 respondents, 137 (97.2%) have successfully donated blood in 2019 while only 70 (49.6%) were able to donate blood in 2020 as seen in Table 1. This demonstrates a decline in the number of blood donors by 48.9%. Moreover, data from the Philippine Red Cross reveals a 59.5% drop from a total of 96,894 individuals who have donated blood in all blood centers within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal in 2019 to a total of 39,196 blood donors in the same area in 2020.

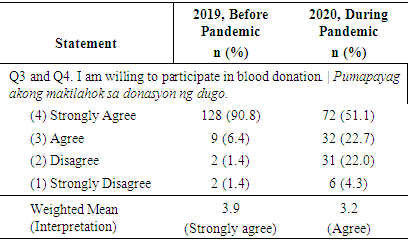

3.3. Intention to Donate Blood Among the Participants of the Study

- In Table 2, the weighted mean in 2019 reveals that the participants have strongly agreed to participate in donating blood. Evidently, the number of participants with strong agreement declined from 3.9 in 2019 to agree in 2020. However, despite this 18% drop from 2019 to 2020, the participants generally showed willingness or intent to donate blood before and during the pandemic.

|

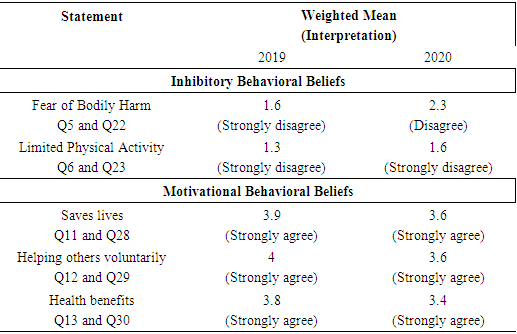

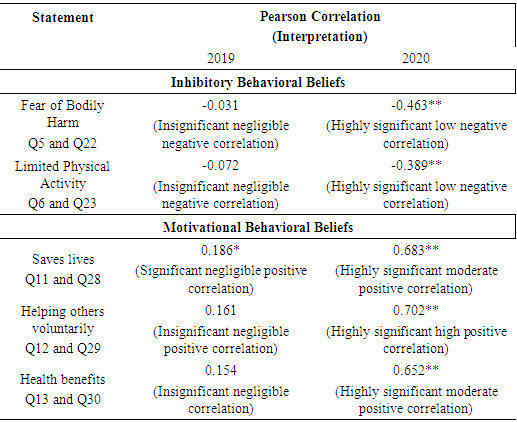

3.4. Behavioral Beliefs and Their Effects on the Willingness of Blood Donors

- As seen in Table 3, there are two inhibitory behavioral beliefs; namely the fear or bodily harm during blood donation (Q5 and Q22) and the belief of limited physical activity after blood donation (Q6 and Q23). The majority of the participants strongly disagreed with both inhibitory beliefs in both years with the exception of the fear of bodily harm in 2020 wherein participants disagreed. Next, most participants strongly agreed in all of the motivational behavioral beliefs which are the belief that blood donation saves lives (Q11 and Q28), the belief that donating blood means helping others voluntarily (Q12 and Q29), and the belief that blood donation has health benefits (Q13 and Q30).

|

|

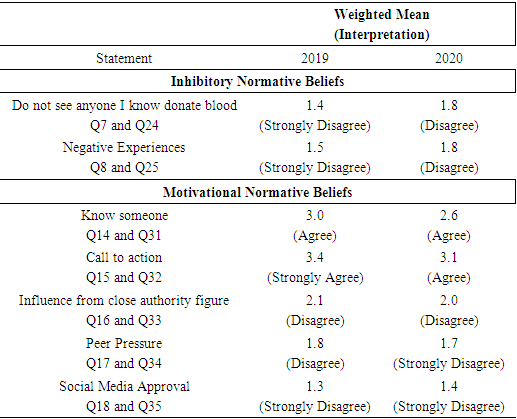

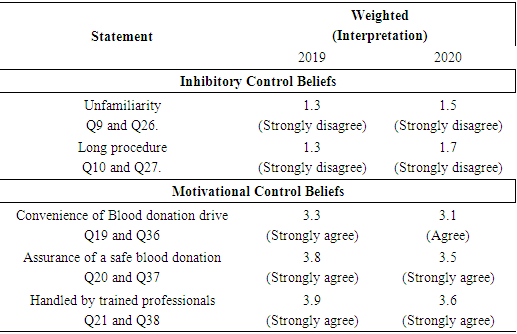

3.5. Normative Beliefs and Their Effects on the Willingness of Blood donors

- In Table 5 under the inhibitory normative beliefs, the majority of participants strongly disagreed in 2019 and disagreed in 2020 that they are not inclined to donate blood if they do not see anyone they know donate blood. (Q7 and Q24). Next, most participants strongly disagreed in 2019 and disagreed in 2020 on being hesitant to donate blood if they hear negative experiences from other people regarding blood donation (Q8 and Q25). In terms of motivational normative beliefs, most participants agreed both in 2019 and 2020 on the belief that they are willing to donate blood because they know someone who has donated blood (Q14 and Q31). On the other hand, most participants strongly agreed in 2019 and agreed in 2020 that they are willing to donate blood out of the call to action from health organizations (Q15 and Q32). Next, most participants disagreed both in 2019 and in 2020 that they are willing to donate blood because of the influence from a close authority figure (Q16 and Q33). Subsequently, most participants disagreed in 2019 and strongly disagreed in 2020 that they are willing to donate blood due to peer pressure (Q17 and Q34). Lastly, most participants strongly disagreed both in 2019 and 2020 that they are willing to donate blood for social media approval (Q18 and Q35).

|

|

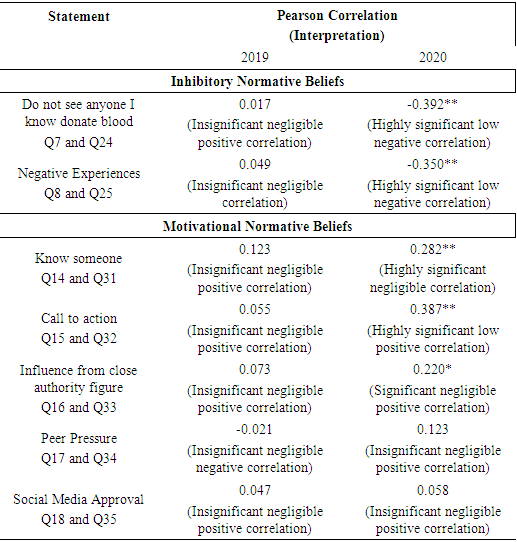

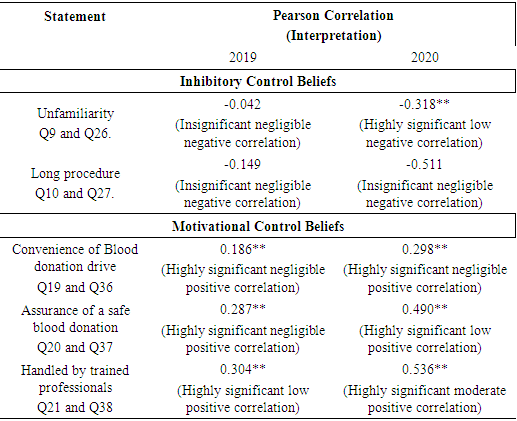

3.6. Control Beliefs and Their Effects on the Willingness of Blood donors

- As seen in Table 7, there are two inhibitory control beliefs; namely the unfamiliarity with the blood donation process (Q9 and Q26) and the belief that blood donation is a long procedure (Q10 and Q27). The majority of the participants strongly disagreed with both inhibitory beliefs in both 2019 and 2020. On the other hand, for the motivational control beliefs, most participants strongly agreed in 2019 and agreed in 2020 on the question regarding their willingness to donate blood due to convenience of a blood donation drive (Q19 and Q36). Lastly, most participants strongly agreed in both 2019 and 2020 that the assurance of a safe blood donation process will motivate them to donate blood (Q20 and Q37) and that they would be more willing to donate blood if it were to be handled by trained professionals (Q31 and Q38).

|

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Decline in the Number of Blood Donors

- Among the 141 respondents and data from the Philippine Red Cross, there was a decline in the number of blood donors by 48.9% and 59.5%, respectively. This significant drop in the number of blood donors coincides with several studies. Blood donations recorded by the DOH National Voluntary Blood Services Program, dropped from 1.38 million units donated in 2019 to 1.04 million units in 2020 [11]. There was a significant 64% drop of whole blood collections from October 2019 to March 2020 in India [12]. On the other hand, blood donation reduction rates varied from 0.07% to 44.2% between 2019 and 2020 in Africa [13]. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) had estimated a 20% to 30% blood supply reduction in all of its regions, noting a 10 to 30% drop in the donor attendance rate in Washington, USA [14,15].

4.2. Intention to Donate Blood Among the Participants of the Study

- The participants generally showed willingness or intent to donate blood before and during the pandemic. The findings of this study agree to a study by Pule et al. [16] recorded that 70.1% of the participants were willing to donate before the pandemic, while Kassie et al. [17] contradicts these findings, which may be due to their participants not being classified and their Likert scale having a “neutral” option. On the other hand, other studies by [18,19] show that certain factors may result in a decrease in the willingness to donate blood supporting the researchers’ findings. The difference in results may be due to their participants not solely being blood donors. However, the participants in this study still agreed or were willing to donate blood during the pandemic.

4.3. Behavioral Beliefs and Their Effects on the Willingness of Blood Donors

- Statements under inhibitory beliefs obtained strong disagreement except for the fear of bodily harm in 2020, while those of motivational beliefs obtained strong agreement in both years. In Pearson Correlation under inhibitory behavioral beliefs, the blood donors are more willing to donate since they do not associate blood donation with any form of bodily harm (Q22) and their physical activities (Q23) will not be limited by donating blood. Moreover, the factors stated are supported by other studies [18,19] where factors which can threaten the safety of the donor such as bodily harm and limitation of physical activities may result in the decline in the donors’ willingness to donate blood. This is in line with the results which show that there is a highly significant negative correlation between the factors in the questions and the donors’ intentions. Under motivational behavioral beliefs, blood donors are more willing to donate blood because they know that blood donation saves lives in 2020 (Q28) and because they know that donating blood helps others in 2020 (Q29). These findings are corroborated with the study which suggested that psychological factors such as altruism and empathy have a significantly positive impact on donors’ behavior [21].Moreover, there is a significant positive correlation between donors who believe that donating blood is a healthy habit to those who donate blood. It supports a study that there is a significant positive correlation between donors who believed that donating blood is a healthy habit to those who donate blood [22].

4.4. Normative Beliefs and Their Effects on the Willingness of Blood donors

- Participants strongly disagreed when asked if they are inhibited from donating blood if they don’t see anyone they know donated blood and because of negative experiences in 2019 which toned down to disagree in 2020. Under motivational beliefs, knowing someone donated blood obtained agreement in both years. Call to action from organizations obtained strong agreement in 2019. Participants disagreed if they were influenced by close authority figures in both years. Lastly, peer pressure attained strong disagreement in 2020 same with social media approval in both years. In Pearson Correlation under normative beliefs, highly significant correlations were found between the beliefs and the donors’ intention to donate blood for questions inquiring if they are willing to donate blood when they don’t see anyone they know donated blood (Q24), negative experiences (Q25) and call to action from organizations (Q32). In Q24, blood donors may be willing to donate blood even if they don’t see anyone they know donate blood in 2020. In Q25, blood donors do not feel hesitant to donate blood if they hear negative experiences from other people regarding blood donation in 2020. Meanwhile, in Q32, blood donors may be willing to donate blood out of the call to action from health organizations in 2020. The findings of the study is in line with the study of Raghuwanshi et al. wherein the majority of the respondents, mostly students, said they would donate blood if there is a call to action from hospitals or blood banks [23].

4.5. Control Beliefs and Their Effects on the Willingness of Blood donor

- Unfamiliarity and the long procedure of the blood donation process obtained strong disagreement in both years. Statements under motivational beliefs attained strong agreement except for convenience of blood donation in 2020. In Pearson Correlation under inhibitory control beliefs, the statement inquiring about the unfamiliarity of blood donation (Q26) states that blood donors are more willing to donate since they do not feel uncomfortable donating blood due to lack of familiarity with the blood donation process in 2020. Under motivational control beliefs, assurance of a safe blood donation (Q37) states that blood donors are more willing to donate because of the assurance of a safe blood donation in 2020. Lastly, blood donation handled by trained professionals (Q38) means that blood donors are more willing to donate blood because the procedure is handled by trained professionals in 2020.However, Q9 and Q26; Q10 and Q27; and Q19 and Q36 have contradicting results with other studies [24], [4], [21] respectively. This may indicate lack of proper promotion of the blood donation process in the country, hence, the blood donors were unable to respond accordingly to the following questions.Consequently, Q20 and Q37 as well as Q21 and Q38 are corroborated by the studies of Nwogoh et al. [26] and Gilaninia et al. [26], respectively.

5. Conclusions

- A remarkable decline in the number of blood donors during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) as compared to before the pandemic (2019) was revealed in all blood centers within NCR, Bulacan, and East Rizal. These blood donors’ intention to donate blood has been influenced by certain factors in the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. In general, blood donors do not agree with the inhibitory beliefs of all three behavioral, normative, and control factors on blood donation, and thus, inhibitory beliefs do not hinder their willingness to donate blood even during the pandemic. Motivational behavioral beliefs such as blood donation being able to save lives, help others voluntarily, and provide health benefits have highly significant moderate to high influence on the donors’ intention to donate blood during the pandemic, whereas the motivational normative belief on the call to action from health organizations has a highly significant low influence on their intention to donate blood during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the motivational control belief of assurance of a safe blood donation has a low influence on their intention to donate blood during the pandemic. Additionally, the motivational control belief of knowing that the blood donation procedure is handled by trained professionals has low and moderate influence on their intention to donate blood before and during the pandemic, respectively.In the face of the pandemic, it is imperative that health institutions understand the hazard of blood shortage for better management of safe and adequate blood supply. Appropriate measures, improved strategies, and adept communication are all necessary to continue motivating voluntary blood donors, bringing into consideration the underlying factors that influence their intention to donate. More so, beyond the problem of declining blood donors, it is important to ponder that failure to respond to inevitable consequences brought upon by the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to even graver impacts in healthcare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to give their warmest gratitude to the following persons, groups and organization: To their thesis guides, Asst. Prof. Ma. Gina M. Sadang, RMT, MSMT, their thesis adviser; Asst. Prof. Julius Eleazar D.C. Jose, RMT, MAEd, MSMT, PhD, their biostatistician; and Asst. Prof. Roberto M. Manaois, RMT, DBA, for their support, consideration, and motivation, for sharing their insights and knowledge, and for patiently reading and checking this paper. To the respondents, this study would not have been possible without their participation and honest answers. To the Philippine Red Cross, who provided them with the statistical information needed to complete this study.To the Lord who gives us strength and for bringing us together in spirit.And finally, to the persons who mean the world to the authors, their families. For their support, guidance and love.

References

| [1] | D. J. Myers and R. A. Collins. (2020, July 31). “Blood Donation”. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525967/. |

| [2] | A. Colley. (2017, January 16). “Health benefits of donating blood” [Online]. St. Mary's Medical Center. Available: https://www.stmaryskc.com/News/2017/January/Health-benefits-of- donating-blood.aspx. |

| [3] | A. Akinbami, E. Uche, A. Adediran, O. Damulak, T. Adeyemo, A. Akanmu, “Lipid profile of regular blood donors”, Journal of Blood Medicine, vol. 4, pp. 39-42, 2013. doi:10.2147/jbm.s42211. |

| [4] | D.M. Valerian, W.I. Mauka, D.C. Kajeguka, M. Mgabo, A. Juma, L. Baliyima, G.N. Sigalla, “Prevalence and causes of blood donor deferrals among clients presenting for blood donation in northern Tanzania”, Plos One, vol. 13, 2018. |

| [5] | S. M. Mathew, M. R. King, S. A. Glynn, S. K. Dietz, S. L. Caswell, G. B. Schreiber, “Opinions about donating blood among those who never gave and those who stopped: A focus group assessment”, Transfusion, vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 729-735, 2017. |

| [6] | R. Agarwal, S. Periyayan, R. Dhanya, L. Parmar, A. Sedai, K. Ankita, A. Vaish, R. Sharma, P. Gowda, “Complications related to blood donation: A multicenter study of the prevalence and influencing factors in voluntary blood donation camps in Karnataka, India”, Asian J Transfus Sci, vol. 10, issue 1, pp. 53-58. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.165840. |

| [7] | C. M. M. Nalupta, “Developing blood services in the Philippines”, ISBT Science Series, vol. 6, pp. 441-445, 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2824.2011.01530.x. |

| [8] | I. Ajzen, “From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior” in Action Control, J. Kuhl, et al., Eds. SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1985, pp. 11-39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2. |

| [9] | N. Hamid, R. Basiruddin, N. Hassan, “Factors influencing the intention to donate blood: The application of the theory of planned behavior”, International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, vol. 3, issue 4, July 2013. doi: 10.7763/IJSSH.2013.V3.259. |

| [10] | A. Schnaubelt, “Factors Influencing a Military Blood Donor’s Intention to Donate: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior,” Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, 2010. |

| [11] | C. Gonzales, “Blood supply nearing critical level amid pandemic – DOH”. INQUIRER.net. Available: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1304163/blood-supply-nearing-. |

| [12] | M. Raturi, and A. Kusum, “The blood supply management amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Transfusion clinique et biologique : journal de la Societe francaise de transfusion sanguine, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 147–151, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2020.04.002. |

| [13] | A. Loua, O. M. J. Kasilo, J. B. Nikiema, A. S. Sougou, S. Kniazkov, and E. A. Annan, “Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on blood supply and demand in the WHO African Region,” Vox Sanguinis, no. vox.13071, 2021. |

| [14] | “Covid-19 Effect, WHO: Blood Supply is Reduced up to 30 Percent,” Nusadaily. com. [Online]. Available: https://nusadaily.com/en/news/covid-19-effect-who-blood-supply-is-reduced-up-to-30-percent.html. [Accessed: 24-Oct-2020]. |

| [15] | S. J. Stanworth et al., “Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on supply and use of blood for transfusion,” The Lancet Haematology, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. e756–e764, 2020. |

| [16] | P. I. Pule, B. Rachaba, M. G. M. D. Magafu, and D. Habte, “Factors associated with intention to donate blood: sociodemographic and past experience variables,” Journal of Blood Transfusion, vol. 2014, p. 571678, 2014. |

| [17] | A. Kassie, T. Azale, and A. Nigusie, “Intention to donate blood and its predictors among adults of Gondar city: Using theory of planned behavior,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 3, p. e0228929, 2020. |

| [18] | K. K. Sahu, M. Raturi, A. D. Siddiqui, and J. Cerny, “‘Because Every Drop Counts’: Blood donation during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Transfusion Clinique et Biologique, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 105–108, 2020. |

| [19] | A. M. S. Sayedahmed, K. A. M. Ali, S. B. S. Ali, H. S. M. Ahmed, F. S. M. Shrif, and N. A. A. Ali, “Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and decrease in blood donation: A cross-sectional study from Sudan,” ISBT Science Series, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 381–385, 2020. |

| [20] | The Investopedia Team, “Statistical Significance,” Investopedia.com, 25-Nov-2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/statistical-significance.asp. [Accessed: 24-Apr-2021]. |

| [21] | F. H. Zubairi and D. A. Siddiqui, “Factors influencing donation behavior: The role of seasonal effects,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2019. |

| [22] | N. Alfouzan, “Knowledge, attitudes, and motivations towards blood donation among King Abdulaziz Medical City population,” International Journal of Family Medicine, vol. 2014, p. 539670, 2014. |

| [23] | B. Raghuwanshi, N. K. Pehlajani, and M. K. Sinha, “Voluntary blood donation among students - A cross-sectional study on knowledge and practice vs. Attitude,” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, vol. 10, no. 10, pp. EC18–EC22, 2016. |

| [24] | Y. A. Jemberu, A. Esmael, and K. Y. Ahmed, “Knowledge, attitude and practice towards blood donation and associated factors among adults in Debre Markos town, Northwest Ethiopia,” BMC Hematology, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 23, 2016. |

| [25] | B. Nwogoh, U. Aigberadion, and A. I. Nwannadi, “Knowledge, attitude, and practice of voluntary blood donation among healthcare workers at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria,” Journal of Blood Transfusion, vol. 2013, p. 797830, 2013. |

| [26] | S. Gilaninia, M. Taleghani, and M. Amenien, “Effective factors on willingness of blood donors to donate blood again in Rasht city: With an emphasis on social marketing approach,” Singaporean Journal of Business Economics and Management Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 42–50, 2013. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML