-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2021; 11(3): 75-89

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20211103.01

Received: Sep. 6, 2021; Accepted: Sep. 22, 2021; Published: Sep. 26, 2021

Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking among Teenagers in Southeast Asia: A Systematic Review

Jewel Hannah Angel, Maegan Barraza, Julia Viana Cerezo, Kimberly Chen, Yara Dawud, Patricia Danielle Dayrit, Carla Michel Javier, Ma. Gina Sadang, Julius Jose

Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Correspondence to: Kimberly Chen, Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background of the Study: Cigarette smoking is one of the most preventable causes of morbidity internationally, especially in low-income countries. It is more prevalent among youth as compared to adults, concluding that the age of initiation follows a decreasing shift. Objective of the Study: This study seeks to determine the prevalence and related risk factors of cigarette smoking among teenage individuals in Southeast Asian countries. Materials and Methods: Identification and selection of relevant studies from years 2011-2020 were from PubMed using an established syntax. A total of 849 articles were identified and screened against a predefined inclusion criteria: research article written in English, ISI or Scopus indexed journal published during 2011-2020, accessible full-text article, number of respondents is > 50 aging from 13-19 years old, originated within Southeast Asia, and prevalence of cigarette smoking and related risk factors are reported. After screening and full-text eligibility assessment, 13 studies were included in the review The extracted statistical findings from each study included the prevalence (in percentage) of cigarette smoking and its related risk factors (in odds ratio). Quality assessment was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. Results and Discussion: All 13 studies were considered to be low risk.The included studies presented that Malaysia has the highest prevalence of teenage smoking while Vietnam has the lowest. In line with this, there is a higher prevalence of smoking among males and older age groups. Furthermore, upon comparing the reported risk factors and odds ratio across all the included articles, the risk factors involved in teenage smoking were male sex, parental smoking, secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, drug use, alcohol use, pro-tobacco advertisement exposure, and positive smoking-related beliefs. Alongside these, the protective factors were being exposed to anti-tobacco messages or advertisements, learning and having knowledge about the hazards or dangers of smoking, believing that smoking is harmful, and having a negative attitude toward smoking. Conclusion: In conclusion, teenagers that initiate conventional and electronic cigarette smoking have been increasing. Aside from male sex, where cigarette smoking prevalence was most common, other risk factors include secondhand smoking, parental smoking, concurrent substance abuse, and exposure to smoking ideals from the environment.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, Teenagers, Southeast Asia, Prevalence, Risk factor

Cite this paper: Jewel Hannah Angel, Maegan Barraza, Julia Viana Cerezo, Kimberly Chen, Yara Dawud, Patricia Danielle Dayrit, Carla Michel Javier, Ma. Gina Sadang, Julius Jose, Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking among Teenagers in Southeast Asia: A Systematic Review, Public Health Research, Vol. 11 No. 3, 2021, pp. 75-89. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20211103.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cigarette smoking is defined as the inhalation and exhalation of smoke coming from a cigarette. This cigarette is made from folded tobacco leaves wrapped with thin paper containing about 600 different ingredients. Some of its notable ingredients are naphthalene, acetone, and the most known ingredient, nicotine. Across the globe, there are more than a billion smokers, wherein 80% reside in either low- or middle-income countries [1]. Furthermore, 19% of adults are current smokers in which 33% are men and 6% are women. While as for the youth who are aged 13-15 years old, there are approximately 24 million smokers globally. In both low- and middle-income countries, the rise in the number of cigarette smokers is attributable to population growth and tobacco industry marketing [2]. According to the 2014 ASEAN Tobacco Control Report, 25 percent of the 1.2 billion adult smokers in the world come from the ASEAN population. From the 2013 ASEAN total adult tobacco smoker percentage distribution, with a population of 625,096,300 ASEAN citizens, Indonesia had the highest percentage of adult tobacco smokers (50.68%) taking up more than half of the population while Singapore had the lowest percentage (0.29%). Adults in this data were considered to be aged 15 and above [3]. There are several risk factors that are associated with smoking initiation among teenagers, such as male gender, parental smoking, friends smoking, socioeconomic status, perception of health hazards of smoking, mass media, spending more time away from home and single parents. The most common reported risk factor associated with smokers is having a family member and/or friend who smokes [4]. In addition to this, teenagers were found to have more pro-smoking behaviors when they were exposed to parental, sibling, and peer smoking. Parental smoking was also associated with the perceived safety of casual smoking and the desire to smoke in response to smoking-related cues like seeing someone else smoke [5]. Moreover, friends have a strong influence on each other and can promote experimentation when there is coercive pressure to engage in risky behaviors such as smoking [6]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoking affects almost every organ in the human body. It causes various diseases and premature death to its affected users. Among the various diseases present in those that practice cigarette smoking, it majorly leads to respiratory diseases; specifically lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [7]. One of the evident diseases also associated with cigarette smoking are cardiovascular disease, mainly coronary heart disease [8]. Other health risks due to smoking include infertility for both men and women, pregnancy problems for women, cataract development in the eyes, type II diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer of other organs [9]. People that do not directly smoke cigarettes, also known as passive smokers, are also affected by those that practice first hand smoking. Secondhand smokers (SHS) may develop the same diseases as those of first hand smokers because they indirectly inhale the same smoke inhaled by the latter [10]. These problems are not only the concern of adults, but also includes teenagers and children. The American Lung Association stated that people that smoke at an early age are most likely to develop an addiction to nicotine and pass away prematurely [11].

1.1. Objectives of the Study

1.1.1. General Objective

- The main objective of this study is to determine the prevalence and related risk factors of cigarette smoking among teenage individuals in Southeast Asian countries.

1.1.2. Specific Objectives

- 1. To investigate relative studies on the prevalence and related risk factors of cigarette smoking using a specific inclusion criteria 2. To determine the prevalence of cigarette smoking during teenage years 3. To identify the odds ratios of risk factors and protective factors of cigarette smoking among teenage individuals in Southeast Asian countries4. To combine and compare the differences and similarities in the reported prevalence and risk factors of the selected studies following the systematic review protocol 5. To assess the implications of the reported risk factors and protective factors

1.2. Significance of the Study

- This study aims to determine the prevalence and risk factors related to cigarette smoking among teenage individuals. The results obtained from the study may benefit the following:

1.2.1. To the Department of Health

- This research may be utilized to prompt the introduction of interventions and improve existing programs in the community implemented by the government and other concerned authorities, directed at regulating tobacco use, as well as discouraging individuals, especially teenagers, from smoking.

1.2.2. To the Community

- The results of this study can help parents, in collaboration with school counselors, increase their awareness regarding the risk factors that influence cigarette smoking among teenagers, in order for them to effectively guide the teenagers.

1.2.3. To the Medical Professionals

- The study shall demonstrate the prevalence of teenage smoking and will serve as a means for medical professionals to focus on discussing the harmful effects of smoking and its prevention among groups with a higher prevalence.

1.2.4. To the Future Researchers

- This study seeks to be of aid to future researchers who are inclined to explore more on the topic of cigarette smoking among teenage individuals and its related risk factors.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

- The researchers utilized a systematic review, a method that involves systematic and comprehensive identification and selection of relevant studies against a predefined inclusion criteria, data extraction of necessary information from the included studies, and finally, data analysis in order to arrive at conclusions in relation to the provided formulated research question.

2.2. Search Strategy

- The search strategy was established using the boolean operators “AND” and “OR.” Hence, the search for journal articles about prevalence and risk factors of adolescent cigarette smoking is done in the database PubMed using the statement “Adolescent OR youth OR teenage AND risk factors OR determinants OR associated factors AND initiation OR likelihood AND prevalence OR incidence OR epidemiology AND tobacco smoking OR cigarette smoking OR e-cigarettes OR electronic cigarettes AND Southeast Asia.” Duplicate titles are excluded, then an initial screening through abstract review is done. Lastly, a full-text article assessment for eligibility is done to determine which studies are to be included in the systematic review using a predefined inclusion criteria.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies were included in the systematic review if they were written in the English language and its year of publication is during the years 2011-2020. Moreover, it should be a research article published in an ISI or Scopus indexed journal and its full-text article is available. As for the respondents involved, there must be a minimum of 50 respondents and their age range must strictly be from 13 to 19 years old. The country of origin of the research must be within Southeast Asia. Lastly, statistical findings on prevalence (in percentage) of cigarette smoking and its related risk factors (with odds ratio) are reported. Studies that lack any of the mentioned aspects were excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction

- Data extraction was performed from the identified articles and reached an agreement as to which are to be included in the systematic review, wherein the following data are to be extracted from the screened journal articles and placed systematically in a spreadsheet:• Title • Author/s • Year of publication• Type of study• Duration of the study • Country where the study was conducted• Age range and/or description of respondents• Sample size• Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking (expressed in percentage)• Risk factors to Cigarette Smoking (with odds ratio)

2.5. Quality Assessment

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies was utilized to evaluate the methodological quality of included studies and determine degree to which a study has approached the risk of bias in terms of its design, conduct, and analysis, by employing the following criteria [12]:• Criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined• Study subjects and the setting described in detail• Exposure measured in a valid and reliable way• Objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition• Confounding factors identified• Strategies to deal with confounding factors stated• Outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way• Appropriate statistical analysis usedStudies that have a score of 50% and above were considered low-risk bias, while those studies with a score lower than 50% will be considered high-risk bias.

2.6. Data Synthesis

- In a systematic review, qualitative methods were utilized in order to synthesize research outcomes drawn from the selected studies, in aim of pooling relevant data regarding prevalence rates of current smoking as well as reported risk and protective factors of smoking among the youth. All relevant data was initially tabularized for easier comparison, thereupon containing prevalence rates as well as identified and protective risk factors as established from pooled odds ratios (OR) and adjusted ratio (aOR) of correlates reported in raw data of the respective journals. Thereafter, general evaluation, commonalities and differences were descriptively discussed to further elaborate on the salient points of major outcomes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Literature Search and Selection of Eligible Material

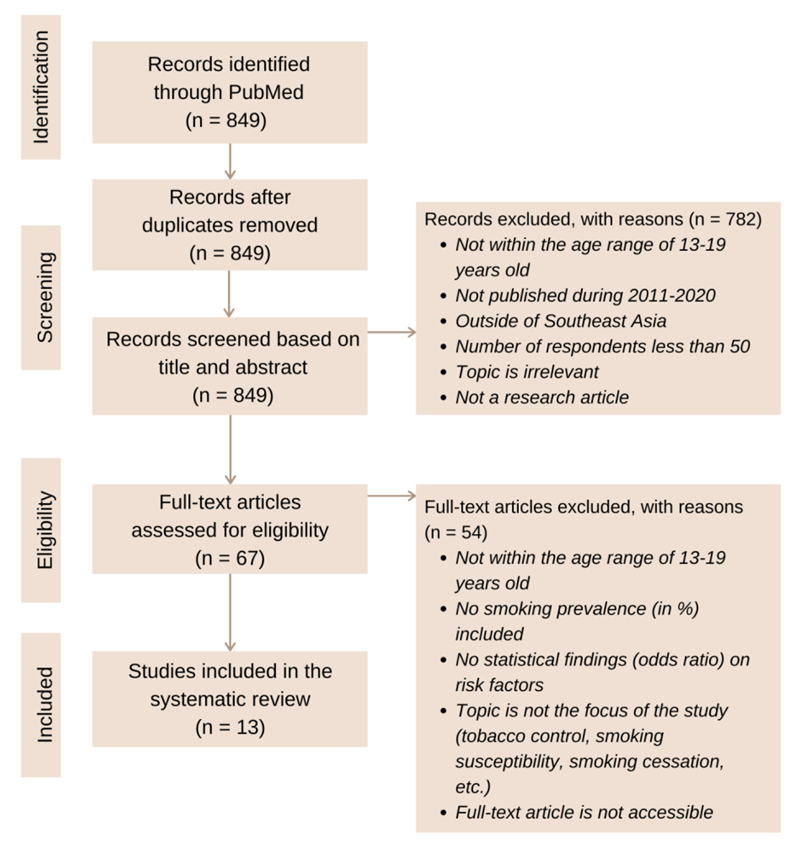

- A total of 849 original articles were identified from the electronic database, PubMed upon input of the search syntax, “Adolescent OR youth OR teenage AND risk factors OR determinants OR associated factors AND initiation OR likelihood AND prevalence OR incidence OR epidemiology AND tobacco smoking OR cigarette smoking OR e-cigarettes OR electronic cigarettes AND Southeast Asia.”, then utilizing search filters by the publication date to be within 2011-2020, and text availability to be free full-text. Out of all identified studies, duplicates were removed using the Remove Duplicates function of Microsoft Excel 2016. There were no duplicates observed. Out of the 849 studies, 782 were excluded as they did not confirm with the inclusion criteria. Out of the 67 studies, 54 were excluded after assessing the eligibility of the full-text article. The reasons for exclusion are the involvement of respondents outside the range of 13-19 years old, the study did not provide smoking prevalence and statistical findings on its risk factors (specifically odds ratio), the topic was irrelevant, and the full-text article was not accessible. Finally, 13 articles were utilized for systematic review. The process for the selection of studies to be included in the research is illustrated in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram of the Study Selection Process for Systematic Review |

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

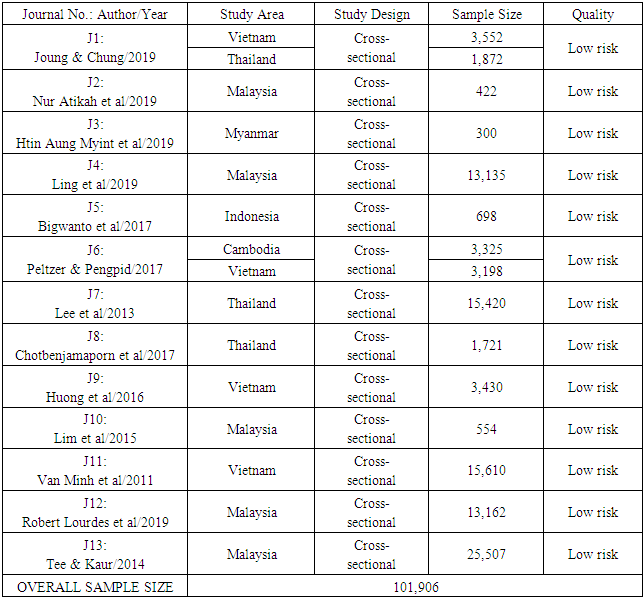

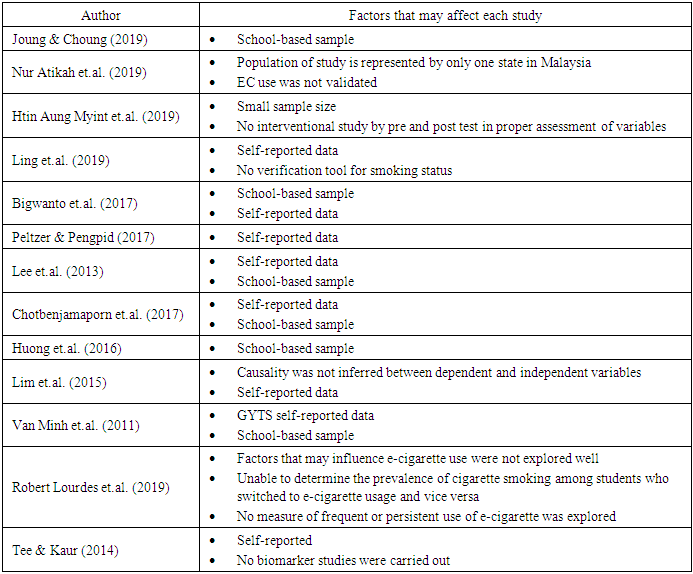

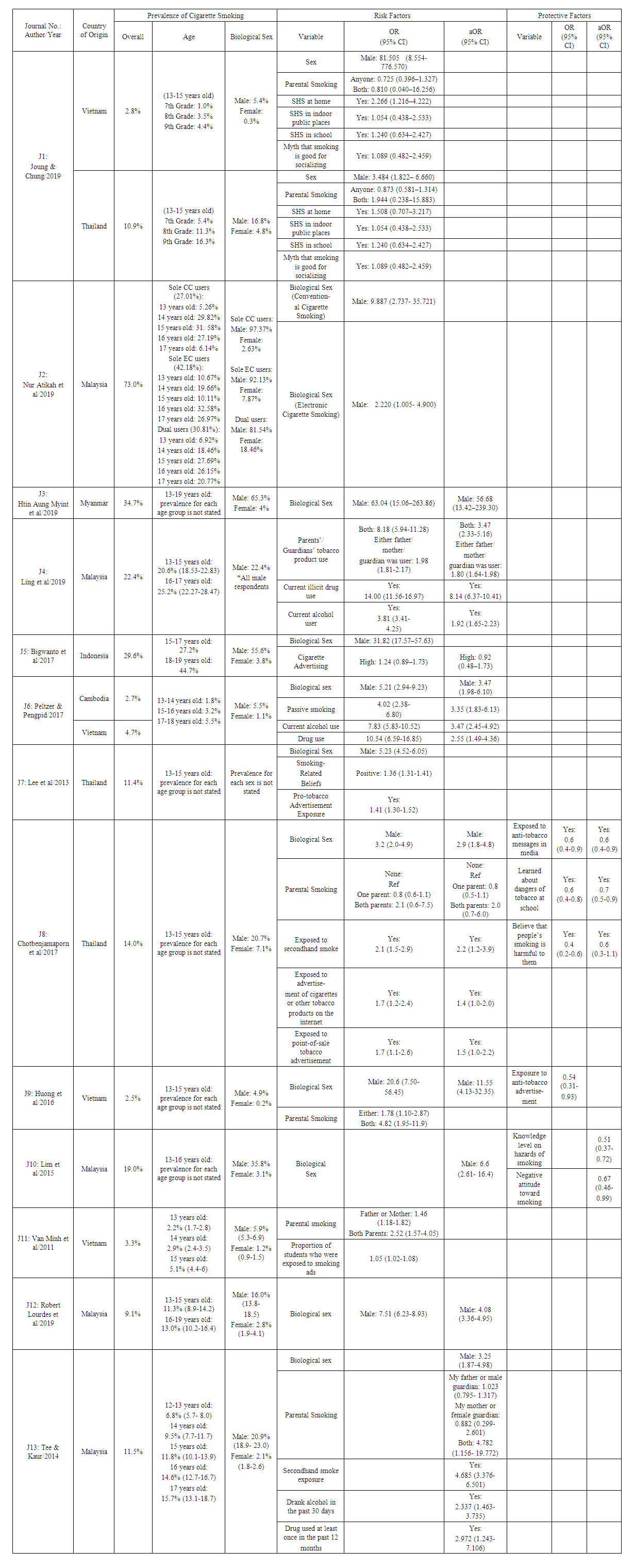

- As shown in Table 1, 13 studies were conducted in Southeast Asian countries between 2011 and 2020. Of these, five were done in Malaysia, two in Vietnam, one in Thailand, one in Indonesia, one in Myanmar, one in Thailand, Vietnam, & South Korea, one in Thailand, Taiwan, & South Korea, and another one was in Cambodia & Vietnam. The data collected in countries that included South Korea and Taiwan were individually stated, hence, all data for South Korea and Taiwan were disregarded. All of the studies accessed through the search were cross-sectional. Sample sizes ranged from 300 to 25,507, wherein the overall sample size amounted to 101,906 respondents. As for the quality assessment, all studies were evaluated to be low-risk bias.

|

3.3. Quality of Included Studies

- In accordance with the JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies, all of the included studies did not indicate any methodological defect as well as significant risk of bias for the reason that the studies scored 50% and above of the quality assessment criteria. Therefore, all 13 articles remain included and considered to be low-risk bias.

3.4. Major Outcomes of Included Studies

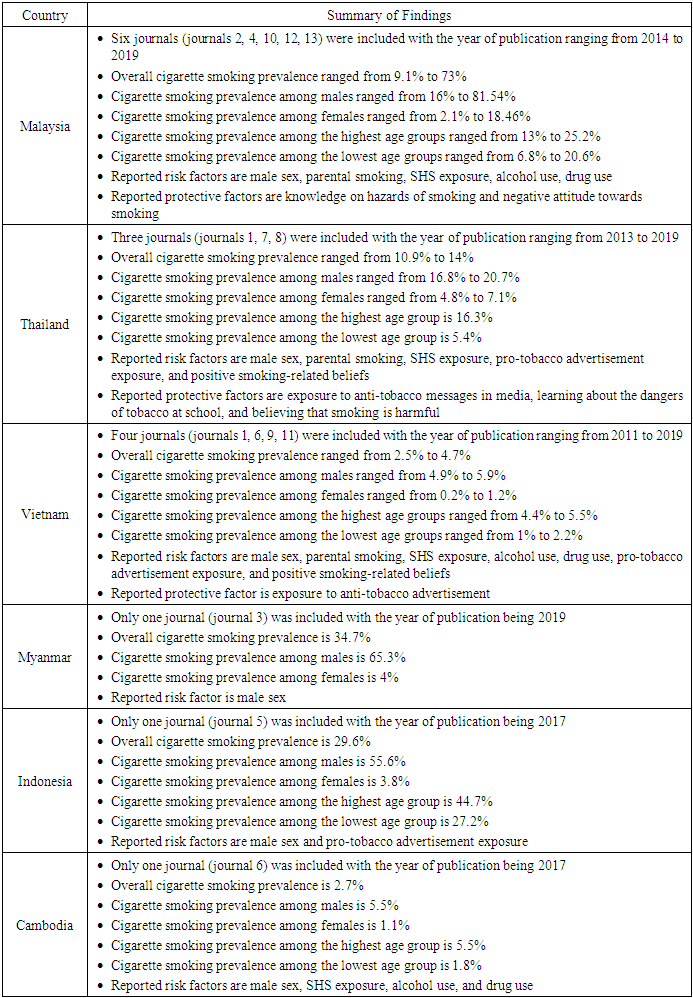

- As shown in Table 2, the researchers have indicated the country of origin, year of publication prevalence of cigarette smoking, of the 13 remaining journals included in the study. The prevalence of cigarrete smoking was divided into three aspects namely: the overall prevalence, prevalence of cigarette smoking in relation to the age, and in relation to the biological sex of the included studies. In addition, the researchers also collated the necessary statistical findings of the related risk and protective factors to cigarette smoking reported per journal article, specifically in odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval.

| Table 2. Major Outcomes on Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Protective Factors of the Included Studies |

3.5. Discussion

- Cigarette smoking is known as one of the highest preventable causes of death globally wherein initiation often begins during one’s youth. According to the WHO, the Southeast Asia Region consists of a third of the world’s youth aged 13-15 years old that use various forms of tobacco. Knowing its danger to those who practice this and to those who are exposed to an environment of smoking, it is important to determine the prevalence and related risk factors of cigarette smoking among teenage individuals in Southeast Asian countries. Therefore, 13 published studies from an online database (PubMed) were reviewed and analyzed in order to differentiate and combine their varying findings. Across the 13 journals, 11 studies (84.62%) were focused on one research locale. Malaysia was the most common research location as it was the country founded in five studies (38.46%), followed by Vietnam (15.38%) and Thailand (15.38%) with two studies respectively, and finally Myanmar (7.69%) and Indonesia (7.69%) with one study each. Aside from this, the remaining two journals by Kyoung H Joung & Sung S Chung (2019), and Peltzer K & Pengpid S (2017), focused on more than one research location (Vietnam and Thailand, and Vietnam and Cambodia respectively). From 2011 and 2013-2016, there was one included journal for each year while in 2017 there were three journals included, and finally five journals were included in the year of 2019. This then gives the study a timeline capable of analyzing the various findings regarding the topic throughout the years. All included studies collated up to 101,906 participants. 11 journals had sample sizes greater than 500 with 25,507 participants as the highest sample size in the study of Guat Tee & Kaur (2014), while two journals had less than 500 participants with 300 participants as the lowest sample size in the study of Htin Aung Myint, et al. (2019) [17,18]. The participants in the included studies were the youth aged 13-19 years old. 38.46% of the studies consisted of 13-15 year olds while the remaining studies consisted of the varying 13-19 year old limitation. 92.31% of the studies included both male and female biological sex labels, but the study of Ling, et al. (2019) only included the male sex [19]. Generally, upon further review of the various data, cigarette smoking in Southeast Asia is more common for the male sex as compared to the female sex.Smoking prevalence was most common in Malaysia, collectively, the prevalence of smokers in Malaysia ranged from 9% to 73%. The most notable data came from the study conducted by Nur Atikah et al. (2019) which stated that 73% of the sample study were electronic cigarette users aged 13-17 years old [13]. Opposing this, Vietnam had the lowest smoking prevalence ranging from 2.5-3.3%, wherein the journal of Huong, et al. (2016) was found to have the least number of smokers [14]. Majority of these smokers come from the male sex ranging from 1.1-97.37%, while the female sex included smokers ranging from 0.2-7.1%. Based on the journal where the highest biological sex percentage was taken from, it was found that Asian males are more likely to smoke compared to females for the reason that it is prevalent in culture where it is more acceptable to be a male smoker compared to female smokers. Similar notions had been observed in a similar study conducted in Tunisia wherein the males had a significantly increased prevalence as compared to females, attributed by normative behavior to that of the male population [20]. As for the cigarette smoking prevalence in the different age groups, there is a direct proportion seen, as the age group increases the cigarette smoking prevalence percentage increases as well. This means that there is a higher risk of smoking in the older adolescents compared to those who were younger. This is specifically seen in the study of Bigwanto et al. (2017) where from the prevalence of 27.2% in the age range 15-17 years old, increased to 44.7% in the 18-19 years old range [21]. This finding was similar to one of the studies in Malaysia by Ling et al. (2019) where their study found that older male adolescents were more likely to be cigarette smokers as peer relationships become more important, hence they are more likely to smoke for social acceptance [19]. Consequently, multiple cross-sectional samples in the US followed a similar pattern, as an observed upward shift toward older age groups was reported, peaking thereafter at 18 years [22]. Smoking includes various risk factors and from the 13 articles that were reviewed, the common risk factors include male sex, parental smoking, SHS exposure, substance use, advertisment exposures, and beliefs. Among these, male sex was reported the most times. Based on the journal where the highest OR was taken from, male smoking is said to be a symbol of masculinity and is considered a social norm while female smoking is not [23]. Furthermore, most youth think that smoking makes boys appear more attractive, successful, and intelligent [24]. This is consistent with a study conducted in Hamadan City, west of Iran, by Barati et al (2015), wherein a typical male smoker was evaluated as less immature, more popular, more attractive, more self-confident, more independent, and less selfish by tobacco smokers [25]. In terms of parental smoking, the ORs of both parents smoking are higher than those of only one parent smoking, which means that the occurrence of smoking is more likely when both parents smoke than when only one parent smokes. According to Ling et al. (2019), teenagers who have parents as smokers have the tendency to imitate their parents’ actions and think that smoking is not harmful. Moreover, the parents’ behavior can be interpreted as an approval for them to start smoking [19]. Furthermore, cigarettes being easily available and accessible in their home can also be a reason [17]. This finding is similar to a study conducted in Boston, Massachusetts, by Mays et al (2014), wherein when parents are current, nicotine-dependent smokers, a longer period of exposure to parental smoking increases the likelihood that their children will follow in their footsteps and become a heavy smoker [26]. Alongside parental smoking, SHS exposure is considered a potent smoking stimulus due to the nicotine inhalation and olfactory stimulation it causes [17]. This finding had also been highlighted in the study conducted in the greater Montreal area, by McGrath et al (2018), in which exposure to airborne nicotine via second hand smoking is a potential risk factor for smoking initiation throughout adolescence. It was also stated that pharmacological exposure to nicotine in the air was linked to smoking expectancies, which are known to trigger smoking initiation [27].As for drug and alcohol use, Tee & Kaur (2014) mentioned that those teenagers that engage in one health-risk behavior are anticipated to take part in more health-risk behaviors [17]. This is further strengthened in a study conducted in four Pacific Islands in Oceania wherein prevalence of smoking is claimed to be concurrent with both alcohol and drug use among the respondents [28]. In relation to pro-tobacco advertising exposure, these advertisements include pro-smoking media campaigns and point of sale display, as well as indirect ones like being offered a free tobacco product by a tobacco company sales representative. Given the consequences of such, one of the provisions of the new Tobacco Product Control Act in Thailand is total ban on advertising [15]. Similar streams of causation was mentioned in a study conducted in the United States, by Agaku & Ayo-Yusuf (2014), wherein adolescents who are exposed to pro-tobacco advertisements are more likely to try new tobacco products [29]. Finally, positive smoking-related beliefs include: people who smoke have more friends, smoking makes people more attractive, and smoking helps people feel comfortable during social events [14]. Anent to this, a study conducted in Madinah City, Al Madinah Region, Saudi Arabia, by Kasim et al (2016), stated that the belief that smokers were more attractive, especially if they were of the opposite sex, as well as the belief that they were more comfortable in social gatherings, increased the probability of adolescents becoming smokers [30].Alongside the risk factors are the protective factors, and the significant ones that were reported are: being exposed to anti-tobacco messages or advertisements, learning and having knowledge about the hazards or dangers of smoking, believing that smoking is harmful, and having a negative attitude toward smoking. As mentioned by Strecher and Rosenstock’s Health Belief Model which was cited by Lim et al. (2015), changes in behaviors happen whenever the perceived threats of a certain behavior outweigh its perceived benefits. In this case, the likelihood of developing cancer prevents the individual from engaging in a health-risk behavior like smoking [16]. In line with this, a study conducted in California, United States of America, by Leas et al (2015), stated that anti-tobacco advertisements with visceral and personal messages may be recalled by a higher percentage of smokers and have a stronger impact on smoking cessation [31]. The summary of generalized qualitative findings from the included articles according to country can be seen in Table 3 below.

|

|

4. Conclusions

- Based on the collated and analyzed data from the 13 journals used in the systematic review, the following statements have been concluded: The prevalence of smokers was found to be more common in the male sex compared to the female sex. The youth that has been practicing electronic and conventional cigarette smoking has been increasing. The common risk factors include the male sex, secondhand smoking, parental smoking, concurrent substance abuse, and exposure to smoking ideals from the environment. In order to mitigate the mentioned risk factors, protective factors were also stated in order to solve the long growing problem of cigarette smoking. Research gaps were also present in the study due to inaccessibility of studies online, comprehension of different languages, type of participants in the study, and incomplete representation of all Southeast Asian countries.The researchers recommend that more studies must be published regarding this topic as all countries in Southeast Asia are not well represented. Although some countries may use this study as a comparison towards their own protocols regarding smoking. It is also recommended that other online electronic platforms are used to have a broader spectrum of included studies. Lastly, performing a meta-analysis on this study should be taken into consideration for more specific findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- First and foremost, the authors would like to express their gratitude to their thesis adviser and appointed mentor, Ma. Gina M. Sadang, RMT, MSMT and Julius Eleazar D.C. Jose, MSMT, MA of the Faculty of Pharmacy at the University of Santo Tomas, for their assistance and encouragement when creating this thesis. They were accommodating whenever there were concerns, considerate when appeals were raised, and willingly helped the authors in parts they were not familiar with. The authors would also like to extend their appreciation to the University of Santo Tomas, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Medical Technology, for giving them the opportunity to contribute to society by writing this thesis. The authors would like to thank the authors of the articles that were used in the systematic review, for without them, no substantial data can be gathered and analyzed.The authors would also like to show their appreciation to their family and friends, for their emotional support whenever problems were encountered. Last but not the least, the authors would like to express their gratitude to the God Almighty, for giving them strength and enlightening their minds when writing this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML