-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2021; 11(2): 33-43

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20211102.01

Received: Apr. 16, 2021; Accepted: May 24, 2021; Published: Jun. 26, 2021

Assessing the Quality, Use and Determinant of Family Planning Services: The Case of Panjgur District, Balochistan

Farzana Hameed1, Sanaullah Panezai1, Shahab E. Saqib2, Kaneez Fatima3

1Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan

2Department of Commerce Education & Management Sciences, Higher Education Department, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

3Institute of Management Sciences, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan

Correspondence to: Sanaullah Panezai, Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Pakistan’s population is growing at an alarmingly high rate which poses a demand for access to family planning (FP) services. As of 2017, the country had a 208 million population and an annual growth rate of 2.1%. In the context of Balochistan province, limited is known about the quality and use of family planning services. This study aims to assess the quality and use of family planning services and associated factors in the Panjgur district of Balochistan province. For this case study, the data were collected from 400 randomly selected respondents through a field survey during October to December 2018 with the help of field assistants. The data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics. The findings show almost two-third had no to little knowledge about the importance of FP. However, 72.50% were using the PF services, mostly by the 35–44year age group. One-fourth were dissatisfied with the availability of female doctors at public health care facilities. Almost two-thirds (64%) received contraceptives through lady health visitors. One-fourth had back pain. The results of regression analysis revealed that in predisposing factors, age, family size, women’s education, and husband’s education and occupation were associated with the use of FP services. Similarly, in enabling factors, monthly income, availability of a female doctor and lady health visitor’s knowledge about FP, ease in access to contraceptives, and quality of FP services were found significant. In the case of need factors, type of illness and health status were associated with the use of FP services. The findings of this study suggest that strengthening of out-reach services of lady health visitors, availability of female doctors at primary health care facilities, awareness about the importance of birth-spacing, and increasing free provision of contraceptives to the married couple can enhance the quality and use of FP services.

Keywords: Family planning services, Use of family planning services, Contraceptives, Basic health units, PPHI, BHU, Birth space, Panjgur, Balochistan, Pakistan

Cite this paper: Farzana Hameed, Sanaullah Panezai, Shahab E. Saqib, Kaneez Fatima, Assessing the Quality, Use and Determinant of Family Planning Services: The Case of Panjgur District, Balochistan, Public Health Research, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 33-43. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20211102.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Family planning (FP) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as, “the ability of individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. It is achieved through the use of contraceptive methods and the treatment of involuntary infertility” (Institute of Medicine Committee 2009). The services of family planning include the provision of contraception (to plan birth spacing, to avoid unintentional pregnancies, and decrease the number of abortions), proposing counseling for pregnant women, help those who wish to perceive, offering infertility treatments and preconception health facilities to improve the health of mothers and infants, as well as provide screening and treatment services for sexually transferred disease (STD). FP services improve women, men, and infants’ health (Gavin et al., 2014). Globally, as of 2019, around 1.1 billion women need family planning services while 842 million use contraceptive methods and 270 million have an unmet need for contraception among the 1.9 billion women of reproductive age group (15-49 years) (World Health Organization, 2020). In developing countries, the use of FP services is low and is generally limited to prevent accidental pregnancies, maternal and infant mortality rates (Apanga & Adam, 2015). Pakistan's population is growing at an alarming rate (Hassan, 2020; Kanwal Ali, 2020) and it has the highest population growth rate in South Asia as per the 2017 census (Qureshi, 2019). To control the huge outbreak of population and infant and mother’s high mortality rates, access to FP services is mandatory. In Pakistan, FP services are provided through the broad network of Basic Health Units (BHUs) (Panezai et al., 2017). The Government of Pakistan has been trying to control the high population growth through the provision of family planning services (Asif & Pervaiz, 2019). Studies have reported underutilization of primary health care services (PHC) services at BHUs (Panezai et al., 2020a; Panezai et al., 2020b; Panezai et al., 2019; Sultana & Shaikh, 2015). The country has made progress in increasing the prevalence of contraceptives over the last three decades. Nevertheless, it is still away from the target (i.e., 50%) set by FP 2020 (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2020). For instance, during 1990-91, the prevalence of any method was only 9% which has now been increased to 25% in 2017-18. Similarly, the use of any traditional method has been increased from 3% in 1990-91 to 9% in 2017-18. Pakistan has committed to increasing the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) among married women by up to 50% by 2020. For achieving this milestone, the government has to make 4.2 million additional women users of family planning services. (National Institute of Population Studies, 2017). Several studies have been conducted to assess the use of FP services. The high growth rate of population in Pakistan is due to the desire for more kids, misconceptions about the usefulness of FP, no access to contraceptive services, or fear of side effects of contraception (Mustafa et al., 2015; National Institute of Population Studies, 2019), and an unmet need for contraception at 31% (Sagheer et al., 2018; Sathar et al., 2015). Lack of awareness on the importance of birth spacing and the unmet need for contraception are the main reasons for population growth (Azmat, 2011). The prevalence of unmet need for FP services in Pakistan is highest among the developed and developing countries (Neelam Punjani, 2018). In addition to this, the socio-economic gap (Aslam et al., 2016), knowledge / practice gap (Haider et al., 2009), persist in the use of family planning methods. Research also reports that fear of side effects for using contraceptives has been identified as the major cause of the unmet need for family planning services in Pakistan (Asif & Pervaiz, 2019; National Institute of Population Studies, 2019). Moreover, socio-economic characteristics such as level of education, husband's education, number of living children, work status, wealth quintile are the other reasons for differences in the current use of contraceptive methods (Iqbal Ahmad and Mumtaz Eskar, 2008). The dilemma with Pakistani rural women is that despite the wish to give gaps in childbirth, they do not use contraceptives. Studies have reported underutilization of primary health care services (PHC) services at BHUs (Panezai et al., 2020a; Panezai et al., 2020b; Panezai et al., 2019; Sultana & Shaikh, 2015). Comparatively, women from the urban areas are much more active in adopting FP services (Sultana & Qazilbash, 2004) where insufficient supplies make the usage of contraceptives limited. A larger share of Pakistani women continues to have an unmet need for FP services (Hardee & Leahy, 2008). According to Shaikh (2010), there is a high unmet need for contraceptives in Pakistan, thus contraceptive prevalence rate continued to be unaffected since 1950s. According to (Khan et al., 2013), despite sufficient time and funding invested to promote the FP services, the contraceptive prevalence rate remains low in Pakistan. In the context of Balochistan province, limited studies have explored access to FP services, particularly in rural areas. According to Waqas et al. (2011), the unmet need was found significantly higher in Balochistan and Sindh provinces compare to Punjab. Another study by Naseem et al. (2020) have identified major bottlenecks in access to Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health (MNCH) services in the Panjgur District of Balochistan, however that study did not cover the family planning services. Research studies have also reported the low use of FP services (Asif & Pervaiz, 2019; UNFPA, 2019). Sagheer et al. (2018) have reported that in Quetta 76% of the married females were willing to adopt the FP methods but only 33.8% had access to it. There is a shortage of literature that has assessed the use of FP in rural Balochistan. Balochistan consists of 34 districts with a population mainly residing in rural areas of the province. This study addresses the question, whether the rural population has access to FP services in Balochistan. Therefore, Panjgur district, being a rural district, with a 74.6% rural population (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2017), was selected purposively because no study was found that has assessed the use of FP services in this rural district before. This study aims to assess the quality and use of family planning services and associated factors in the Panjgur district of Balochistan province.

2. Material and Methods

- This study used a case study research design for the collection of data. The data were collected through a field survey in Panjgur District of Balochistan province, Pakistan during October to December 2018 with the help of field assistants in the study area. Setting Panjgur is the district of the Makran Division in Balochistan province. According to Population Census 2017, the current population of Panjgur District is 316,385 persons and the total area is 16,891 square kilometers. It is located at 63°04'50"-65°20'11". East longitudes and 26°08'54"-27°17'55" North latitude (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2017). The district has 3 tehsils and 16 union councils. The climate of the district is extremely hot in summer and heat strokes beginning in a large number but the winter is severely cold and northern winds blow in January and February 2018 to make the weather unbearably cold (Sarfraz, 1997). Research studies have reported the lowest (29%) use of contraceptives in Balochistan (Asif & Pervaiz, 2019). However, there is limited literature that has assessed FP services at the district level. Therefore, the Panjgur district was selected purposively because no study was found that has assessed the use of FP services in the district before. Participants and Sample Design The participants for this study were married women of reproductive age i.e., 15 to 49 years. Simple random sampling was selected for choosing the participants. The reason for opting for simple random sampling was to ensure randomness and representativeness of the sample. According to the Census conducted in 2017, the total population of Panjgur District is 316, 385. There are 42628 households in Panjgur District. Out of the total population, the male population is 166731, whereas the female population is 149654. (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2017). As the current study is aimed at exploring the women’s use of FP services, thus, the female respondents were surveyed at their households. We selected a household as a unit of analysis for this study. Following the formula of Yamane (1967), a sample of 399 was drawn.

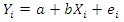

| (1) |

2.1. Data Analysis Methods

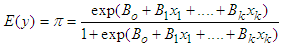

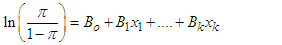

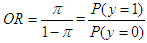

- For analysis, both descriptive and inferential statistics were applied. We used a t-test and chi-square test for comparison of mean values of the selected study variables. Moreover, the binary logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between the dependent variable, i.e., use of FP services (yes=1, 0=otherwise), and the predisposing, enabling, and need factors. The generalized logistic regression can be expressed through the following formula.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

3. Results

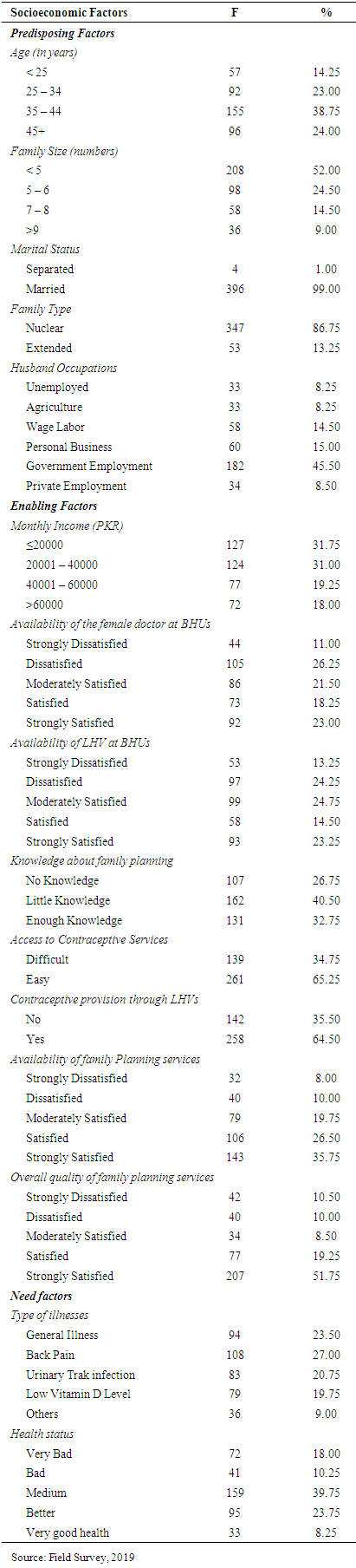

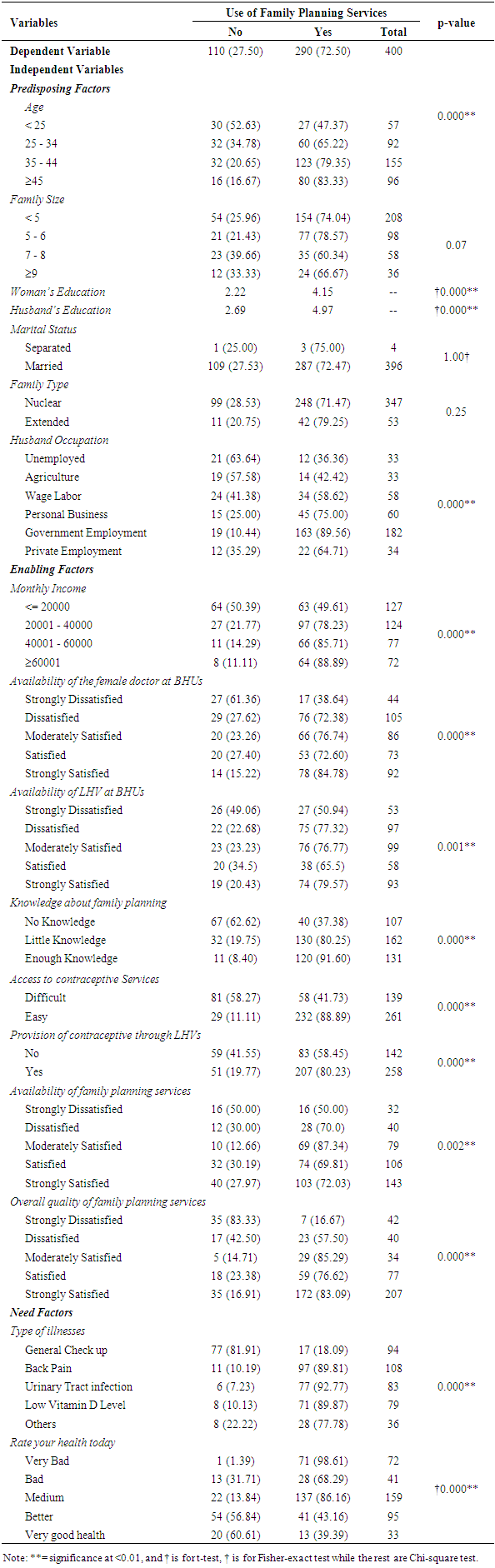

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Socioeconomic Factors of the Respondents

- Results in Table 1 show that the two-fourth (38.75%) of the women were from the age group of 35 to 44 years, from families < 5 members and 99% belonged to the married group. These women were living in nuclear families. Most of the women’s husbands had formal job (i.e., government employees). The majority of participants belonged to the lower-income group, having <20000 PKR per month. Among these participants, little more than one-fourth (26.25%) were dissatisfied with the availability of female doctors at the BHUs. Similarly, 24.25% were dissatisfied with the availability of LHVs, whereas 40.50% were having little knowledge about the FP. However, 65.25% reported that they have easy access to contraceptives. Of the total, 35.75% and 51.75% of the women were strongly satisfied with the availability of FP services and with the overall quality of FP services, respectively. In need factors, 27% of them, had back pain. Out of total women, 39.75% were having fair health where only 8.25% are very healthy.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

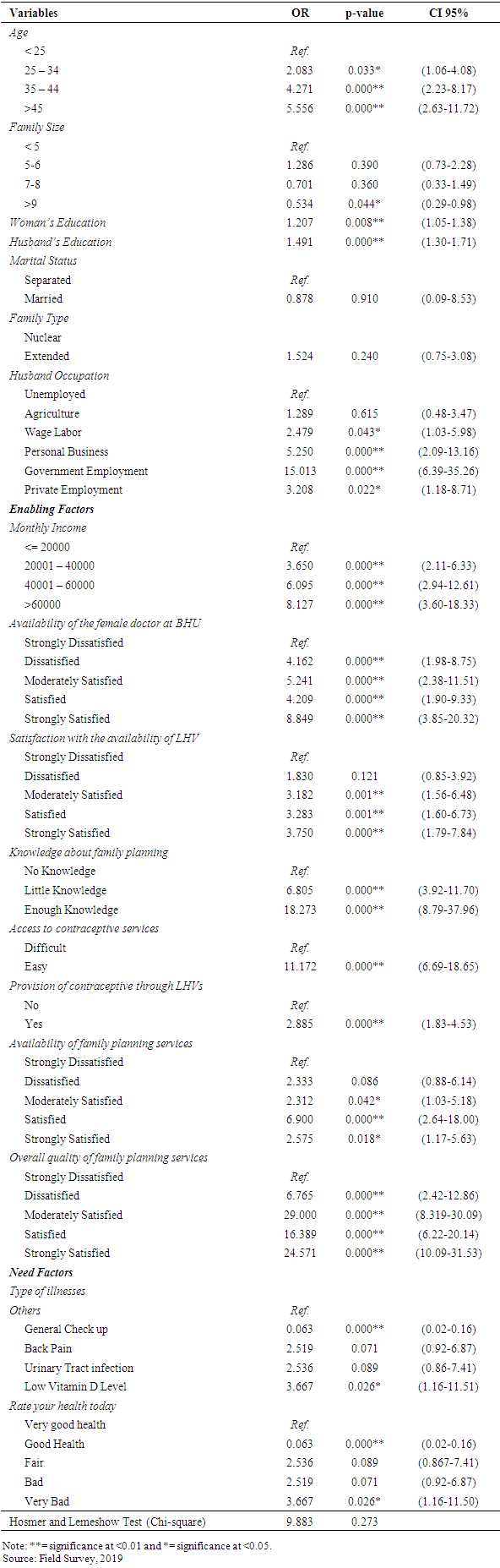

- The use of family planning services is determined by predisposing, enabling, and need factors (Andersen, 1995). The findings of this study showed that almost three-fourth (72.5%) of the total respondents were using family planning (FP) services. Almost similar findings i.e., the use of FP services at 71.5% have been reported by Haider et al. (2009). The national contraceptive prevalence of Pakistan has been as low as 34% (National Institute of Population Studies, 2017). The findings of the current study showed that the use of FP services in the study area is high compared to the national rate. In the predisposing determinants, age, family size, and husband’s education have been identified as important determinants of the use of FP services. The interesting point to note is that age was positively associated with the use of FP services. The use of FP services increased with an increase in age among married women. The reason for this increase is obvious as the young married couples want to have kids in their early stage of marriage. The findings of this study are consistent with those of (National Institute of Population Studies, 2017). The current study findings also revealed that the women with large family sizes were using fewer family planning services. This shows their desire for having large families, that is the reason they used FP services less. These findings are consistent with those of Mustafa et al. (2015) who reported that in Pakistan the married couples in all provinces were not exercising family planning methods mainly due to their desire for more kids. Our findings also revealed that an increase in the level of education of the respondents and their husbands increases the use of family planning services. The current findings support those of Asif and Pervaiz (2019). This shows that educated women with educated husbands tend to use more FP services compared to less or uneducated women. These findings reveal the importance of knowledge about the benefits of FP for the lives of mothers and children. Compared to the women with unemployed husbands, those with employed husbands used more family planning services. This implies that working-class husbands have more knowledge about the importance of FP services and they had more desire for birth spacing. In the case of enabling factors, the average monthly income, satisfaction with the availability of female doctors and LHVs, knowledge about the FP services, level of difficulty in access to contraceptives, availability of family planning services, and perception about the overall quality of family planning services were the significant determinants of the use of FP services in the study area. In the case of income, similar findings to the current study are reported by National Institute of Population Studies (2017) that revealed that the use of FP services increases with an increase in wealth of the households. Moreover, our findings are also consistent with Iqbal Ahmad and Mumtaz Eskar (2008) who reported a significant increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate from 16% in presently married females within the lowest quintile to 43% of these in the highest quintile. The findings suggest that the married couples from poor economic backgrounds should be targeted for using the FP services through enhancing access to free contraceptives. Moreover, our findings also showed that women with more knowledge about the importance of FP services tend to use more FP services that are consistent with findings reported by National Institute of Population Studies (2017). These findings suggest that effective media campaigns should be launched to increase the level of awareness among married couples. The findings of our study also revealed that almost two-thirds (64.5%) of the women reported provision of contraceptives through the lady health visitors (LHVs). This shows a better picture of the outreach services provided by the Family Planning program through LHVs. The percentage of provision of contraceptives in our study is better than those reported by National Institute of Population Studies (2017) i.e., 56.8%. These findings imply that if the Family Planning Program with the support of the People Primary Health Care Initiative (PPHI) invests more in strengthening the outreach services by LHVs, then the use of family planning services can be increased. We also endorse the findings of Neelam Punjani (2018) who suggest the integration of family planning facilities in all first-level health care services to decrease the unmet need of FP services. Among the need-based factors, the results showed that poor health is positively associated with the use of family planning services. Research has established the health benefit of spacing pregnancies and delaying birth and FP services (Kavanaugh & Anderson, 2013). The findings of our study showed that women health deteriorated with no use of FP services. These show that health can be maintained with spacing births and using FP services.

5. Conclusions

- It is challenging to provide family planning (FP) services in Pakistan. Women are constrained by cultural limitations that make access to FP services difficult. The results of this study have shown that use of FP services among women is largely associated with the predisposing, enabling and need factors. Pakistan as a signatory to the FP 2020, a global initiative for improving FP services to women, has committed to improving the FP services in the country by increasing the contraceptive prevalence rate to 50% by 2020. However, Pakistan had been unable to achieve the set target by 2020. Enhancing the use of FP services in rural areas is challenging. Due to the cultural limitations, in the study area provision of FP services through the Lady Health Visitors (LHVs) Program is of high importance. The network of LHVs should be used properly in reaching the rural poor. The findings of the current study suggest that the robust coordination of the Family Planning Program with the People Primary Health Care Initiative (PPHI) can surely improve the quality of FP services in the study area. As committed in FP 2020, funding should be enhanced to FP program for the reduction in unmet needs of FP among the rural population. Moreover, strengthening of the outreach FP services by lady health visitors is direly needed to reach the less educated and poor women because free of charge provision of FP services, particularly the contraceptives can convince rural women for birth spacing and reduction of unmet needs for contraception. Moreover, the “Hub and Spoke Model” of Mother and Child Health (MCH) Services, an initiative of the PPHI for providing the integrated MCH services at the basic health units (BHUs) level should be replicated and expanded throughout the province to provide the family planning services to the rural poor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are grateful to the staff of primary health care (PHC) facilities Panjgur District who helped in data collection.

Funding

- This research study received no funding.

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML