-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2020; 10(5): 143-157

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20201005.02

Received: Dec. 7, 2020; Accepted: Dec. 21, 2020; Published: Dec. 26, 2020

Household Dynamics in the Financing of Health Care and Its Implication on Universal Health Coverage: A Systematic Review

Njuguna K. David1, Wanja Mwaura-Tenambergen2, Job Mapesa3

1Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

2Department of Health Systems Management, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kenya Methodist University, Nairobi, Kenya

3Department of Public Health Human Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kenya Methodist University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Njuguna K. David, Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

There is strong evidence that out-of-pocket expenditure, negatively affects healthcare utilization, leading to adverse health consequences. This systematic review explores the financial burden of treatment and medication for households, and the extent to which this burden caused them to forgo or discontinue treatment. We included 20 studies conducted in America, Africa, Asia and the Pacific. All relevant studies reviewed conclude that out of pocket expenditure decreases the utilization of healthcare services because they make them more costly. The reviewed studies rely on both existing data and primary data collected through surveys. Thirteen studies reported a cost-related reduction in medication adherence and loss to follow up. Four studies reported a cost-related reduction in healthcare services demand while two studies reported the impact of out-of-pocket payments on the choice of healthcare provider. One study reported on the impact of out-of-pocket payments on the choice of healthcare services. Financing strategies should be put in place to further reduce household out-of-pocket costs, reduce or subsidize time and transportation costs for households seeking public and private care; and increase transparency of costs and quality to improve household decisions. Drug plan managers should also consider the effects that medication cost-sharing levels may have on health outcomes in children with asthma, particularly with regard to the use of controller medications.

Keywords: Out-of-pocket, Health insurance, Healthcare utilization, Households, Financial risk Protection

Cite this paper: Njuguna K. David, Wanja Mwaura-Tenambergen, Job Mapesa, Household Dynamics in the Financing of Health Care and Its Implication on Universal Health Coverage: A Systematic Review, Public Health Research, Vol. 10 No. 5, 2020, pp. 143-157. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20201005.02.

1. Introduction

- Universal health coverage (UHC) is a global health priority anchored in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, target 3.8. It ensures financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all [1]. Health financing is critical for achieving universal health coverage by raising adequate funds for health in ways that ensure people can use needed services and they are protected from financial risk [2]. The Kenya National Health Account shows that the health sector is financed by three major sources including, the government, households (out of pocket expenditure), and donors. During the fiscal year 2015/16, the Kenyan government was the major financier of health, contributing 33% of current health expenditure, up from 31% in fiscal year 2012/13. The household contribution to current health expenditure was 32.8% in fiscal year 2015/16. There was an increase over the fiscal year 2012/13 estimate of 32%. However, the donor contribution reduced to 22% of current health expenditure in fiscal year 2015/16, down from 25.5% in fiscal year 2012/13 [3]. The huge proportion of household contribution to current health expenditure is worrying and continues to be a problem despite the abolition of user fees at public health centers and dispensaries. This can be attributed to the cost-sharing policy in public hospitals [4], low health insurance coverage in Kenya [5], and low expenditure on health by the government [6]. When healthcare systems don't protect care seekers financially, entire households can be pushed or trapped into poverty or experience catastrophic expenditure due to payments required to receive needed health services. While this is a fundamental requirement of UHC, guaranteeing financial protection has proven to be a daunting challenge across most countries but especially so in resource-constrained settings where prepayment mechanism are not well developed. [7]. The cost of health care will include both direct and indirect expenses, such as out-of-pocket (OOP) for health care. Some households will not earn income because they will not be able to work. Also, the households incur transport cost while seeking healthcare. The direct and indirect health expenditure normally constitutes a large proportion of a household’s total expenditure and may push many into poverty [8]. The level of financial protection from out-of-pocket (OOP) health payments is estimated through two statistical parameters: (i) the proportion of a country’s population that has a high share of OOP spending for healthcare, which is considered a substantial financial burden on household budgets and is defined as catastrophic expenditures; and (ii) the proportion of the population that falls below the poverty line due to OOP health spending, which is defined as impoverishment. Governments, the World Bank (WB), the World Health Organization (WHO) and civil society organizations have recognized that ensuring access to health services for everyone without causing financial hardship is crucial to sustainable economic growth and development. Therefore, closely monitoring the progress toward these goals can support evidence-based policy decisions and enrich the global knowledge regarding the approaches to achieving UHC despite severely limited resources [9].A “financial catastrophe” for a household is experienced when the out-of-pocket expenditure health expenditure is greater than or equal to 40% of its non-subsistence income [10]. Consequently, households have to cut down on basic necessities such as education, food, and clothing [11,12] In 2010 it was estimated that about 150 million people globally experienced catastrophic health care expenditure annually [13]. In Low-and Middle Income Countries (LMIC) catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditure for health pushes around 100 million people into poverty annually. Studies have shown that household characteristics, such as incidence of hospitalization, household size, head of household’s educational level, and the presence in the household of elderly or disabled persons, also affect the possibility of incurring in catastrophic health spending [14]. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment is indicative of a lack of financial protection for households, which is the key goal of universal health coverage [15].A recent analysis of catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in Kenya established that 12% of households that sought health care experienced catastrophic health expenditures while another 4% were impoverished. Further, the incidence of catastrophic expenditures was highest in the lowest quintile [16]. To meet the costs of illness, households adopt coping strategies that are potentially ‘risky’ for their future economic welfare, such as selling critical assets and sinking into inescapable debt [17–19]. Furthermore, pro-poor policies within the public sector, for example exemptions and waivers, have been found to be relatively ineffective in protecting the poor [20–22]. Household interactions with health services, and the costs people incur due to illness, are central to the performance of health care interventions, particularly their coverage and equity implications. Existing cost barriers and quality weaknesses deter use of health services, particularly by the poor, so services are often ineffective in reaching the poor and generate less benefit for the poor than the rich [23–25]. Very little work has been done to understand the impact of catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditure on access to healthcare and healthcare utilization. This review aims to examine the impact of household out-of-pocket health expenditure globally over time and its impact on healthcare utilization and implication on Universal Health Coverage.

2. Methods

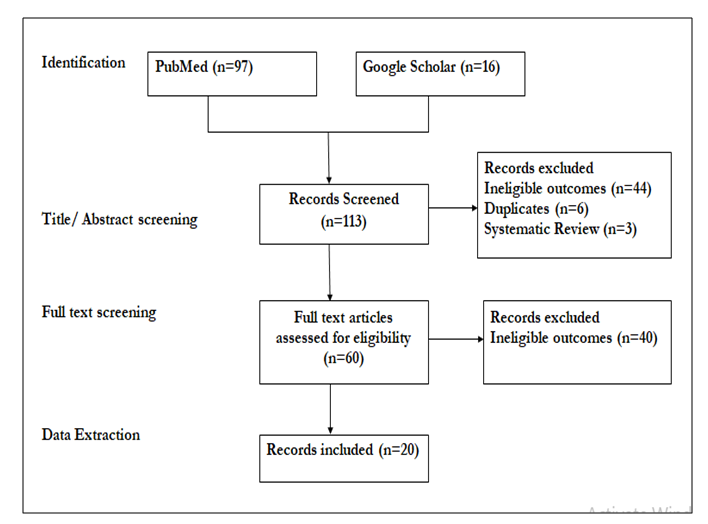

- The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in conducting this systematic review. This systematic review was not registered in PROSPERO.Search strategy.A systematic search for published literature in English was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar. References of retrieved articles and reports were screened to identify additional published studies. The key words used in the search were catastrophic health expenditure, out of pocket payment, impoverishment, household, impact, and their synonyms. The following search strategy was used ((((((Out of pocket) OR (Household spending)) AND (healthcare demand)) OR (healthcare access)) OR (healthcare utilization)) AND (catastrophic health spending)) OR (impoverishment).This review aimed to identify all relevant published studies which considered the financial burden of treatment and medication for households, and the extent to which this burden caused them to forgo or discontinue treatment. Specifically, we were looking for studies that described household that decide to forgo, postpone or abandon their treatment; or undertake less treatment or medication than advised and the role of out-of-pockets costs in this decision. See figure 1 below.

| Figure 1. Literature screening process |

3. Results

- Overall characteristics of publicationsMost studies, 12 out of 20 publications, originated from the America, 6 originated from Africa while two studies originated from Asia and the pacific. Majority (19) were published in peer-reviewed journals though a summary technical report was also included. The included publications were published between 2002 and 2019. The external validity of these studies is clear due to the fact that the most of studies discuss the generalizability of their results. The impact of out-of-pocket payment on adherence and loss to follow upThere is also strong evidence that out-of-pocket expenditure, negatively affects medication adherence, leading to adverse health consequences. In particular, one study [27] reported that drop-out from care was mainly due to poverty in people with severe mental disorder. Depression and higher disability increased the risk of interrupting medical visits. This could result in non-adherence to prescribed medications and loss to follow-up which is common in the treatment of depression. Bello et al highlighted the challenges of providing maintenance hemodialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in Nigeria in 2013. Since the patients have to pay out-of-pocket for dialysis, coupled with the fact that the cost of a single session of dialysis exceeds the national minimum wage in Nigeria, only 3.3% of the patients had thrice weekly dialysis, 21.7% dialyzed twice weekly, 23.3% once weekly, 16.7% once in two weeks, 2.5% once in three weeks and 11.7% once monthly. At the time of review, 8.3% of the patients had died while 38.3% were lost to follow-up [28].In 2004, Piette et al. sought information about the cost-related underuse of medications in the United States. They found out that 18% of respondents cut back on medication use owing to cost in the previous year, and 14% used less medication at least monthly. Although rates of underuse varied substantially across treatments, prescription coverage and out-of-pocket costs were determinants of underuse across medication types [29]. These findings are consistent with that of Kennedy et al who estimate the national prevalence rates of medication noncompliance due to cost and resulting health problems among adults with disabilities in the United States in 2002. About 1.3 million adults with disabilities did not take their medications as prescribed because of cost, and more than half reported health problems as a result. Severe disability, poor health, low income, lack of insurance, and a high number of prescriptions increased the odds of being noncompliant as a result of cost [30]. Hennessy et al showed that spending at least 5% of household income on drugs and pharmaceutical products was significantly associated with cost-related prescription non-adherence in Canada [31].Després et al compared adherence to prescribed medications in privately insured patients from Quebec, Canada, with different patient reimbursement timing and levels of patient out-of-pocket expenses. They found out that there was no difference in medication adherence between the immediate (n = 1,345) and deferred patient reimbursement (n = 437; difference, 0.0%; 95% CI, -3.0 to 3.0). Patients with the highest patient out-of-pocket expenses were less adherent than those with the lowest patient out-of-pocket expenses (difference, -19.0%; 95% CI, -24.0 to -13.0); however, patients with no patient out-of-pocket expenses were less adherent than those with low patient out-of-pocket expenses (difference, -9.0%; 95% CI, -15.0 to -2.0) [32]. Law et al in 2012, determined the prevalence of cost-related non-adherence and investigated its associated characteristics, including whether a person has drug insurance in Canada. Cost-related non-adherence was reported by 9.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 8.5%–10.6%) of Canadians who had received a prescription in the past year. In the adjusted model, that people in poor health (odds ratio [OR] 2.64, 95% CI 1.77–3.94), those with lower income (OR 3.29, 95% CI 2.03–5.33), those without drug insurance (OR 4.52, 95% CI 3.29–6.20) and those who live in British Columbia (OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.49–4.42) were more likely to report cost-related non-adherence. Predicted rates of cost-related non-adherence ranged from 3.6% (95% CI 2.4–4.5) among people with insurance and high household incomes to 35.6% (95% CI 26.1%–44.9%) among people with no insurance and low household incomes [33].Wagner et al examined the relationship between co-payment amounts and four types of cost-related underuse in the United States in 2008. They showed that patients who reported paying higher co-payments were substantially more likely to report cost-related medication underuse. People with co-payments of $30 or more had 4.5 higher odds of under using medication due to cost in the last year than people whose co-payment was less than $5. Besides, there was a strong positive association between co-payments and cost-related medication underuse [34]. In 2004 Piette et al examined health insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of care in the United States. Fewer Veterans Health Administration (VA) patients reported cost-related medication underuse (9%) than patients with private insurance (18%), Medicare (25%), Medicaid (31%), or no health insurance (40%; P <0.0001). Underuse was substantially more common among patients with multiple co-morbid chronic illnesses, except those who used VA care. The risk of cost-related underuse for patients with 3+ co-morbidities was 2.8 times as high among privately insured patients as VA patients (95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.5), and 4.3 to 8.3 times as high among patients with Medicare, Medicaid, or no insurance. Moreover, individuals reporting cost-related medication underuse had glycosylated hemoglobin levels (A1C) levels that were substantially higher than other patients (P <0.0001), more symptoms, and poorer physical and mental functioning (all P <0.05) [35].In 2017, the estimated prevalence of cost-related non-adherence in 2014 among Canadians aged 55 years and older was 8.3%. The prevalence was significantly higher among Canadians who were younger, in worse health, poorer or without private health insurance. In 2014, the regional prevalence of cost-related non-adherence among older adults ranged from 5.7% in Alberta to 9.5% in Saskatchewan in the Atlantic Provinces. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in the regional population prevalence rates. With adjustments for all potential predictors of cost-related non-adherence, Canadians aged 55-64 years were more than 3 times as likely to report cost-related non-adherence than those aged 65 years and older (adjusted OR 3.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.27-5.40); Canadians who reported having fair or poor health were 75% more likely to report cost-related non-adherence than someone of very good or excellent health (adjusted OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.12-2.38); Canadians with lower incomes were more than 3 times as likely to report cost-related non-adherence than those with above average income (adjusted OR 3.59, 95% CI 2.32-5.55); and Canadians who did not have private health insurance were more than twice as likely to report cost-related non-adherence than those with private insurance (adjusted OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.56-3.10) [36].Medeiros et al assessed the impact of the rapidly rising costs of health care on the health-seeking behavior of Latino registered voters, and the impact of high medical costs on their economic status in the United States in 2012. They found that a third of Latinos used up all or most of their savings while a quarter of Latinos skipped a recommended test or treatment due to high medical costs, rates that are particularly high given that our sample is of Latino registered voters. Furthermore having health insurance was not statistically related to preventing economic hardship due to medical costs for Latinos [37].Ungar et al examined the effect of cost-sharing on the use of asthma medications in asthmatic children from Canada in 2008. The annual number of asthma medication claims per child was significantly lower in the high cost-sharing group (6.6) compared with the zero (7.0) and low (7.2) cost-sharing groups (P <.001). Children in the high cost-sharing group were less likely to purchase bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, and leukotriene receptor antagonists compared with the low cost-sharing group (odds ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.67–0.86) and were less likely to purchase dual agents compared with the low cost-sharing group (odds ratio, 0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.66–0.75) [38]. This finding is consistent with that of Karaca-mandic et al who also analyzed the association of medication cost-sharing with medication utilization and use of hospital services among children with asthma in the United States in 2012. Greater cost-sharing for asthma medications was associated with a slight reduction in medication utilization and higher rates of asthma hospitalization among children 5 years and above. An increase in OOP medication costs from the 25th to the 75th percentile was associated with a reduction in adjusted medication utilization among children ages 5 to 18 (41.7% of days versus 40. 3%, p = 0.02), but no change among younger children [39]. The impact of out-of-pocket payments on healthcare services demandOut of pocket payments had a negative impact on the demand for healthcare services among households. When patients were required to pay for healthcare services, the demand among poor and rural households declined. One study [40] that estimated the Fairness in Financial Contribution (FFC) index and evaluated the prevalence of catastrophic health expenditure concluded that richer households were more likely to consult a health care provider when they were sick compared to the poor. In addition, around 40% of the population, when sick with chronic or acute conditions, did not seek care from a medical provider. Another study, [41], that assessed how responsive the Democratic Republic of Congo health system was in providing financial risk protection showed that over 17% of individuals living in sample households who reported an illness or injury in four-week period prior to the survey did not seek out health care services. For those who needed primary care and did not use it, money was reported to be the primary reason for not seeking care. A third study [42] conducted in Liberia showed that households forgoing healthcare (HFH) incidence was over 5 times the incidence of impoverishing expenditure and 3 times the incidence of CHE (at the higher threshold). Given the high rates of poverty in Liberia, the implication is that these households could not afford or access the healthcare services that they need. It is important to remember that those households that forgo healthcare may not spend money on healthcare but the impact of untreated illness may then lead to impoverishment in other ways such as reduction in productivity and/or income. In addition there were lower OOP health expenditures and healthcare utilization rates in rural areas. This suggests that healthcare services in rural areas are inaccessible due to either supply issues (i.e., there are few or no healthcare providers) and/or demand issues (i.e., rural households are poorer and cannot afford to buy healthcare). The fourth study [43], which assessed Impact of Out-of-Pocket Expenditures on Families and Barriers to Use of Maternal and Child Health Services in Asia showed that among those who reported illness, the poor were consistently less likely to obtain care for their sick children and overall. Rural households were also less likely to make use of healthcare than urban households. The impact of out-of-pocket payments on the choice of healthcare providerOne of the publications [44] that examined whether and under what conditions out-of-pocket, transportation, and time costs influenced Kenyan households' choice of medical provider for childhood diarrheal illnesses showed that many households utilized informal care. The informal care, relative to formal care, cost the same but was of worse quality suggesting that such households were making poor medical decisions for their children. Another study [45] that sought to understand the broader determinants of health seeking behavior showed that most study participants preferred to consult a private healthcare provider. Due to the fact that private medical care is relatively expensive, the participants believed that they could get quality care from private healthcare providers and thereby save some money for such catastrophic expenditures related to episodes of illness.The impact of out-of-pocket payments on the choice of healthcare servicesOne study [46] that investigated the utilization of both inpatient and outpatient services, estimated the incidence of catastrophic health spending, and the impoverishing impact of OOP health spending showed that there were substantial inequalities in utilization of inpatient care. Those in the poorest quintile sought more outpatient care than those in the richest quintile. The poorest quintile, on average, had 0.021 admissions per person per year compared to 0.036 (71.4% higher) for the richest. By contrast, the richest quintile had 71.4% more inpatient admissions than the poorest. In total, OOP spending was estimated at 25 USD per person per year, and OOP health spending results in an additional 1.29% of households falling into poverty. These inequalities compromise the patient management and quality of care there by resulting in poor health outcomes among household members. See the table 1 below.

| Table 1. Table of evidence |

4. Discussion

- The study provides empirical evidence that out of pocket expenditure decreases the utilization of healthcare services because they make them more costly. Besides, our results strongly support the concept that out of pocket expenditure has adverse impacts on health outcomes [47–50]. These results also reinforce the fact that out of pocket expenditure causes a financial barrier that decreases both medication adherence and influences household’s decision with regards to choice of providers and services sought, which negatively affects health outcomes. There is need to reduce the prevalence of catastrophic health expenditure by focusing on increased financial protection to poor and expanding government financed benefits by including and expanding inpatient coverage and adding drug benefits [40]. Moreover, financing strategies should be put in place to further reduce household out-of-pocket costs, reduce or subsidize time and transportation costs for households seeking public and private care; and increase transparency of costs and quality to improve household decisions [44]. Cost-related medication adherence problems could have serious health consequences that should be taken into account when employers, government agencies, and private health insurers define the limits of drug coverage for chronically ill patients. In the absence of comprehensive drug benefits, physicians should become active partners in patients’ decisions regarding foregoing essential medications [35]. Increasing prescription drug coverage through insurance may significantly improve medication adherence and health outcomes for large numbers of chronically ill adult [29]. A multi-sectoral approach is needed to address the provision of basic amenities, the availability of safety nets to pay for health care is crucial to avoid catastrophic expenditure and the provision of community-based health promotion programs are essential to improve health seeking behaviors whilst simultaneously promoting and protecting health [45].This review also points out the need for coverage for special conditions like diabetes and asthma which are chronic and life threatening. Prohibitive costs are a major barrier to utilization thus financial protection interventions, including prepayment schemes, exemptions and fee waiver strategies, need to target households of persons conditions like depression [27] and asthma [28,38]. Governments of sub-Saharan African countries need to subsidize the cost of renal replacement therapy in order to improve access to maintenance dialysis and renal care and thereby, improving outcomes in patients with ESRD [28]. Drug plan managers should also consider the effects that medication cost-sharing levels may have on health outcomes in children with asthma, particularly with regard to the use of controller medications [38].Our findings show that the impacts of out of pocket expenditure on healthcare utilization vary across studies. The great diversity outlined above makes it difficult to ascertain causal relationships between these variables. Also, most studies reviewed use a revealed preference method that could potentially be influenced by other factors, such as provider characteristics [51]. To circumvent this problem; future research could employ a blend of revealed and stated preference methods. Our review includes two important caveats. Even with the numerous several studies that focus on estimating catastrophic health expenditure and its determinants [14,52–55] the data used are not always collected with the primary objective to test the relationship between impacts of out of pocket expenditure and healthcare utilization. Furthermore, there exist a lack of experimental studies, notably because real experiments on this topic are not always possible for ethical reasons [51].

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, our findings support calls to reconsider how healthcare services should be financed and guarantee financial protection for households. Decision-makers should incorporate financial protection interventions, including prepayment schemes, exemptions and fee waiver strategies that target households. Also, policymakers could focus on reducing time and transportation costs for households seeking public and private care; and increase the transparency of costs and quality of care to improve household decisions There is an urgent need to investigate adequate levels of cost-sharing for a country or an insurance scheme. Besides, more research on households forgoing healthcare should be included in standard financial risk protection measurements to capture the potential gains from universal healthcare coverage. Finally, health financing reform agendas must incorporate a strategy for getting data used in the design of financial risk protection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML