-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2020; 10(4): 123-132

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20201004.03

Received: Aug. 5, 2020; Accepted: Aug. 25, 2020; Published: Sep. 15, 2020

Effects of Health Insurance Schemes on Utilization of Healthcare Services and Financial Risk Protection: A Systematic Review

Njuguna K. David1, 2, Wanja Mwaura-Tenambergen2, Job Mapesa3

1Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

2Department of Health Systems Management, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kenya Methodist University, Nairobi, Kenya

3Department of Public Health Human Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kenya Methodist University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Njuguna K. David, Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Universal health coverage (UHC) assures healthcare utilization and financial risk protection. Health insurance schemes are highly variable in the scope of the benefits package, the magnitude of premiums, deductibles, copayments, and the range of providers and health facilities participating in the networks. The variability has different effects utilization and financial risk protection. This systematic review explores the effect of various models of health insurance on utilization of healthcare services, and financial risk protection. We included 22 studies conducted in 17 countries that implement different health insurance schemes. Overall, evidence on the impact of health insurance on financial protection varied across studies reviewed. Seven studies reported a reduction in out-of-pocket expenditure, two studies had no statistically significant effect; and one study reported an increase in out-of-pocket expenditure. While 14 studies found a positive effect on healthcare utilization, six studies had no statistically significant impact on utilization of healthcare. The findings of this review show that enrollment in various insurance schemes can protect households and individuals from catastrophic out-of-pocket spending and increase healthcare utilization. The consistent evidence of the positive effects of health insurance highlights the need to explore creative and responsive insurance schemes contextualized to meet the needs of different groups and achieve UHC.

Keywords: Health insurance, Health financing, Universal Health Coverage, Access, Financial risk protection

Cite this paper: Njuguna K. David, Wanja Mwaura-Tenambergen, Job Mapesa, Effects of Health Insurance Schemes on Utilization of Healthcare Services and Financial Risk Protection: A Systematic Review, Public Health Research, Vol. 10 No. 4, 2020, pp. 123-132. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20201004.03.

1. Introduction

- Universal health coverage (UHC) is driving the global health agenda [1]. It is anchored in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, target 3.8 that aims at providing access to key promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative health interventions for all at an affordable cost [2]. The World Health Report of 2010 is exclusively devoted to universal health coverage and provides recommendations for changing health financing systems to achieve UHC [3]. A suitable health financing mechanism enables the health sector to achieve its goal of ensuring access to quality and affordable health care for all while guaranteeing financial risk protection.Health financing remains one of the key issues in both developed and developing countries. The Abuja declaration recommends governments to allocate 15% of the total national expenditure budget to health [4]. However, the level of spending on health for many developing countries remains below the Abuja Declaration threshold [5-8]. While many countries would like to have universal health coverage for their citizens, economic downturns experienced in the recent past, and the continued rise in healthcare costs have not provided an opportunity to do so. Therefore, many countries cannot provide quality health services to their citizens without enduring financial hardship, which is against the World Health Assembly resolution 58.33 (2005) on “Sustainable health financing, universal coverage, and social health insurance” [9].Health financing systems include revenue collection, pooling, and purchasing functions, which are central to achieving universal coverage [10]. Health insurance is based on the principle of pooling of funds and entrusting the management of such funds to a third party that pays for healthcare costs of members who contribute to the pool. It secures financial access to health care for individuals and protects against potentially devastating economic shocks incurred while seeking health care. In addition to serving the typical functions of risk insurance, health insurance has developed as a mechanism for financing or pre-paying a variety of health care benefits, including routine preventive services, whose use is neither rare nor unexpected [11]. There are four main modalities of health insurance: (1) private health insurance, (2) national health insurance, (3) social health insurance, and (4) community health insurance. Private health insurance could be a mandatory or voluntary insurance system where the revenue is created by the premium paid by the insured whereas national health insurance covers the health care costs of all the citizens where the financing source is the national or state government [12]. The revenue for health insurance is usually funded by tax or fixed budget allocation [13]. The social health insurance scheme is a mandatory insurance plan where the financing source is the employer or employee from salary or wage [14]. Community-based health insurance is voluntary health insurance where the premium is paid out of pocket by the insured members and this the pool is generated within a defined community [15]. A mandatory health insurance scheme is one in which there is a legal requirement for certain groups or entire population to become members. The insured with the help of their employers can pay the whole cost of the services they use, not just a small part of the cost which in practice is all that user charges can collect. The Contributions are community rated, i.e. based on the average expected cost of health service for the entire insured group instead of individuals or groups risk of illness [16]. Examples include the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) in Kenya and Tanzania, and the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Ghana.Social health insurance (SHI) is another organizational mechanism for raising and pooling funds to finance health services, along with tax-financing, private health insurance, community insurance, and others [17]. Tax-funded systems use general revenue taxation to pay for the bulk of all healthcare services. While these services are delivered predominantly through a public sector delivery system, some private providers collect their fees from the government and private hospitals and clinics. This system is being implemented in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and New Zealand [18].For voluntary health insurance schemes, the decision to join and/or pay for premiums is voluntary [19]. For instance, Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI) is a form of micro health insurance which is mainly used in rural areas in developing countries [20]. It helps low-income households manage risks and reduce their vulnerability in the face of financial shocks. It is anchored on voluntary membership, non-profit objective, linked to a health care provider (often a hospital in the area), risk pooling and relies on an ethic of mutual aid/solidarity [21]. A low-income household is one whose income is low, relative to other households of the same size. A household is commonly classified as low-income, and can be eligible for certain types of government assistance, if its income is less than twice the poverty threshold. In 2012, a family of four would be considered low income if their taxable income was below $45,000 [22].There is a growing need to take stock of the effects of different health insurance schemes on utilization of healthcare services and financial risk protection. This systematic review provides a more in-depth look at the effect of the different models of health insurance schemes on utilization of healthcare services, and financial risk protection. The results are essential for policymakers in their formulation of interventions to achieve UHC.

2. Methods

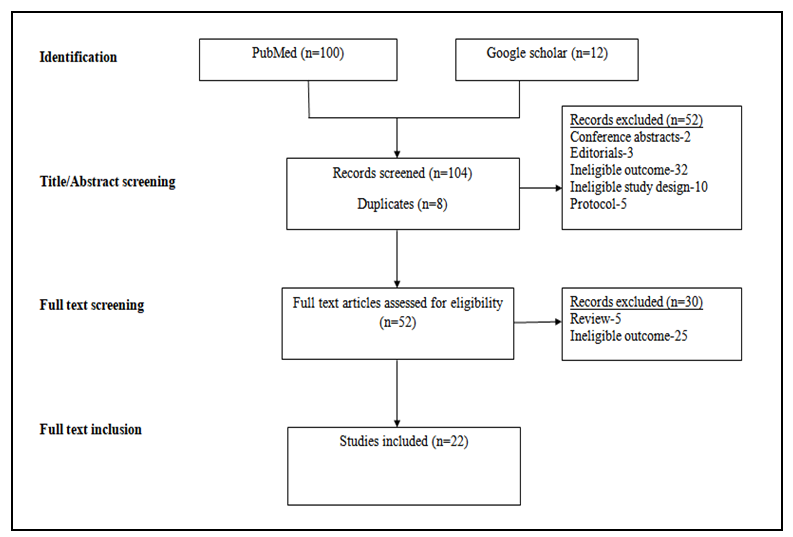

- This review adopted the PRISMA guideline for systematic reviews to design the search for research articles in English. This systematic review was not registered with PROSPERO. See figure 1 below

| Figure 1. Literature screening process |

3. Findings

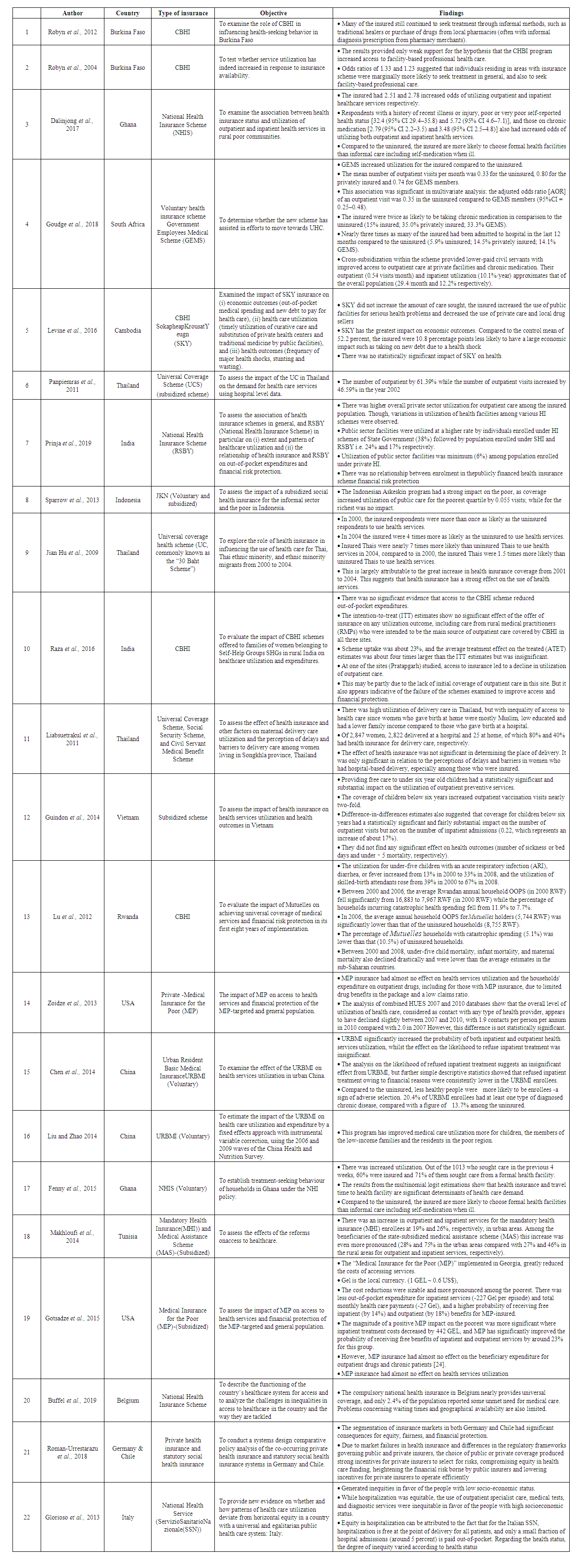

- The studies included were published between 2004 and 2019. The 22 studies were conducted in 17 countries globally - seven from Africa, ten from Asia, three from Europe and two from America. These countries were selected to exhibit a range of income levels, UHC-related progress, and different health insurance schemes. The types of insurance schemes varied from CBHIs, National Health Insurance Schemes, voluntary, and subsidized schemes. Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics and the findings.

| Table 1. Summary of Findings |

4. Discussion

- The findings of this review show that enrollment in various insurance schemes can protect households and individuals from catastrophic out-of-pocket spending [25-29] [24] [30]. Policy makers and program implementers however need to take caution of the risk of moral hazard among the insured individuals [31]. It is also evident that utilization responds to price. The perceived cost saving to the insured households increases demand which constraints the health system. Reduced out of pocket expenditures leads to a sharp increase in the demand for health care resulting in resource and funding constraints [26). Consequently, this affects the quality of services provided by the hospitals including long queue times, inadequate consulting time provided by doctors, poor quality services. These findings are supported by that of Timothy Besley who reported that receiving health insurance alone is not enough to ensure equal access to healthcare and the barriers to admission to healthcare services go beyond simple conceptions of monetary affordability. Indirect economic healthcare costs, such as long waiting times, loss of earnings when seeking care or travel costs, can reduce the usage of healthcare even when it is free of charge [32]. The increased healthcare utilization defined in this context as access to healthcare, have financial repercussions for sustainability, especially for National insurance schemes. Those more likely to need care are registered and subsequently utilize health services. The URBMI scheme faced a conflict between the modest financing level and the increased healthcare demand it has created [33]. Program implementers need to consider trades-offs and strike a balance between the demand and supply sides before implementing any insurance scheme. Erlyana and others recommended interventions to reduce travel distance especially in areas with underdeveloped transportation infrastructure and less availability of public transportation in addition to expanding health insurance [34]. Moreover, governments need to strengthen the supply of health services can also increase to meet this demand. This can be achieved through provision of good quality, and effective health care.However, some of the schemes implemented do not offer financial risk protection. The Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) report of 2019 revealed that the share of out-of-pocket payments account for 57.6% of expenditure on dental care, 29.8% on pharmaceutical, 13.1% on inpatient care, 7.5% on ancillary services and 5.6% on long-term care. The share of out-of-pocket payments on dental care expenditure was high but similar to the European average (57.6% in 2016, compared to a European average of 59.2% based on 10 countries). This share increased from 50% to 58% in the 2004-2016 period in Belgium [35]. Moreover, the strong impact of the Askeskin scheme for the poor lead to a slight increase in out-of-pocket health payments in urban areas. This is most likely due to an increase of relatively more expensive hospital care for which the cost has not been fully covered by the Askeskin insurance [36]. There is also no evidence that the Health Care Funds for the Poor (HCFP) insurance in Vietnam provided financial protection thus the anticipated out-of-pocket payments may deter even those with health insurance to seek health care. For the schemes studied in India, there was no relationship between enrolment in a publicly financed health insurance scheme and utilization of care or financial risk protection. The MIP insurance had almost no effect on health services utilization and the households' expenditure on outpatient drugs, including for those with MIP insurance, due to limited drug benefits in the package and a low claims ratio [24]. To ensure financial risk protection, policy makers should re-consider the design of the insurance benefit packages. Majority of the out-of-pocket expenditures is on account of outpatient consultation. However, the same is not covered under current publicly financed schemes. Policies should be realigned to ensuring financial risk protection and on strengthening provision of primary care. Besides, policy makers need to design health insurance schemes, which take into account the current socio-economic, socio-demographic and epidemiological profile of the population while reinforcing the financial and supply capacity of the health insurance system. Lu et al also reported that Mutuelles enrollees from the poorest quintile in Rwanda still had significantly lower rates of utilization and higher rates of experiencing catastrophic health spending than Mutuelles enrollees in higher quintiles. The Mutuelles copayments may have prevented indigent enrollees, who live under the extreme poverty line of $0.32 per day, from seeking needed care, or placed a heavy economic burden on them when care was sought [29]. SSN in Italy has a universal and egalitarian public health care system but exhibits a significant degree of socioeconomic status related horizontal inequity in health services utilization [37]. Raising scheme uptake and reducing differentials between benefit packages for voluntary schemes can ameliorate inequities locally. Increasing the breadth, or the proportion of the population covered, would ensure more of the population benefit from any rise in the depth and scope of services available.Some of the schemes implemented created new incentives for adverse selection. Open enrolment in Germany increased access in private health insurance but created new incentives for adverse selection when favorable risk users initially sought very low coverage and then changed to more comprehensive coverage when they developed unfavorable risk factors [38]. Moreover, adverse selection limited SKY's ability to grow [25]. Scaling up social health insurance needs to take into account possible behavioral response by providers, and consider adequate provider payment systems so as to avoid a backlash in the provision of public health care. Careful policy design and regulation including abolishing choice and making social health insurance compulsory for the whole population, or introducing more incremental measures to tackle risk selection and increasing access to coverage should be put in place. Integration of current fragmented pooling funds would also improve the anti-risk capability of insurance schemes.While insurance should increase utilization, poor utilization was also observed. The effect of Assurance Maladie à Base Communautaire (AMBC), on controlling self-treatment in this study was limited. Both the insured and uninsured populations maintained self-treatment rates of over 55% [39]. Policy makers should explore strategies to improve the quality of diagnosis, prescription and treatment within households and throughout the informal sector. There is need target and exempt a range of health services such as dental care, pharmaceutical goods, inpatient care, ancillary services and long-term care from official payments and deliver them free of charge. The low uptake of voluntary health insurance emphasizes the importance of other programs to increase access to health care for the rural poor.

5. Study Limitations

- An important limitation of this review is that it combines studies from 17 countries, which are culturally and economically diverse. The studies also differ in their objective. However, combining studies from various countries with heterogeneous objectives is not unusual for reviews on Health insurance coverage in SSA.

6. Conclusions

- The findings of this review show that enrollment in various insurance schemes can protect households and individuals from catastrophic out-of-pocket spending. This body of research yields consistent and significant findings of the relationship between health insurance and, healthcare utilization and financial risk protection. Health insurance facilitates ongoing care with regular health care providers and reduces financial barriers to obtaining those services that constitute or contribute to appropriate care. Different settings may benefit from the different insurance schemes contextualized to meet the needs of their populations. This should give program planners more confidence to explore creative, responsive insurance schemes to best meet the needs of their populations and achieve UHC.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML