Njuguna K. David1, Elizabeth Wangia2, Stephen Wainaina3, Theresa Watwii Ndavi4

1Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

2Monitoring & Evaluation Specialist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

3Independent Consultant, Nairobi, Kenya

4Economist/Independent Researcher, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Njuguna K. David, Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Since the establishment of County Governments in 2012, County health departments have led in priority setting, Planning and Resource Allocation (PSRA) in line with the functions prescribed under the fourth schedule of the constitution. While devolution has expanded decision spaces concerning PSRA, it has introduced new sets of actors including the county assembly and the county executive. It has also introduced new requirements such as preparation of the County Integrated Development Plans, program-based budgets, and sector working group reports among others. This new environment complicates the PSRA process whose ultimate goal is to contribute towards a more efficient, responsive and accountable health department. The PSRA processes are anchored in the The Public Finance Management Act, 2012 (PFM Act 2012) which prescribes a continuum of critical activities and requirements to facilitate priority setting, resource allocation, budget alignment with existing resource envelops, legislation and budget execution. Health remains the most devolved of all social sectors thus its success speaks to the success of devolution.

Keywords:

County, Health, Planning

Cite this paper: Njuguna K. David, Elizabeth Wangia, Stephen Wainaina, Theresa Watwii Ndavi, Health Sector Planning at the County Level in Kenya: What has Worked, Challenges and Recommendations, Public Health Research, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 87-93. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20201003.01.

1. Introduction

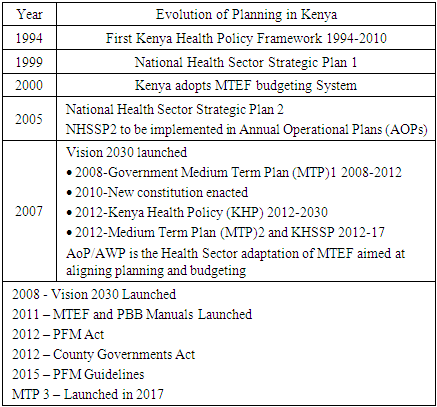

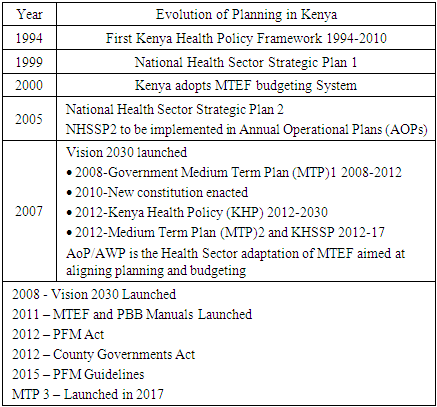

The Government of Kenya is deeply committed to the improvement of the health of its population [1-3]. Health care is one of the government’s social responsibilities and forms the foundation for accelerated overall national development. Efforts to integrate a vision for improved health into the national development agenda dates to independence [4] and through Vision 2030, and other sector-specific policies and strategies. It is envisaged that Kenya will become a globally competitive middle-income country by 2030 [1]. To realize this dream, the health sector must contribute by ensuring it has a healthy population to drive development. In the presence of a finite amount of resources, and competing country priorities, planning for high impact, evidence-based interventions are paramount [5,6]. Adherence to the budgeting cycle is crucial to ensuring that health sector priorities are captured at the right time, for financing [7].Before the Constitution of Kenya was promulgated in 2010, planning and implementation of development programs were the responsibility of the central government. Sector-specific planning processes were previously guided by the Ministry of Planning and National Development, while the Ministry of Finance guided the budgeting process. These two processes had a weak linkage, resulting in a mismatch between the planning and budgeting cycles. The Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) was introduced in the early 2000s, to address this misalignment. The various sectors would identify priorities and bid for resources at the hearings in the Sector Working Group, prepare AOP planning tools, guidelines, and resource envelopes for planning units, based on the indicative government resources allocated from the Sector Working Group hearings [8].Before 1994, the health sector had no sector-specific policy and strategic plan. Health sector investments were guided by the Session Paper [9] that identified disease, poverty, and ignorance as priorities that government investments were to be directed at. From 1994-2010, a policy framework was developed that had an overall goal of making health services more effective, accessible, and affordable to all Kenyans, implemented through 5-year medium-term plans (National Health Sector Strategic Plans (NHSSPs)). Table 1 illustrates the evolution of planning in Kenya [10].Table 1. Evolution of planning in Kenya

|

| |

|

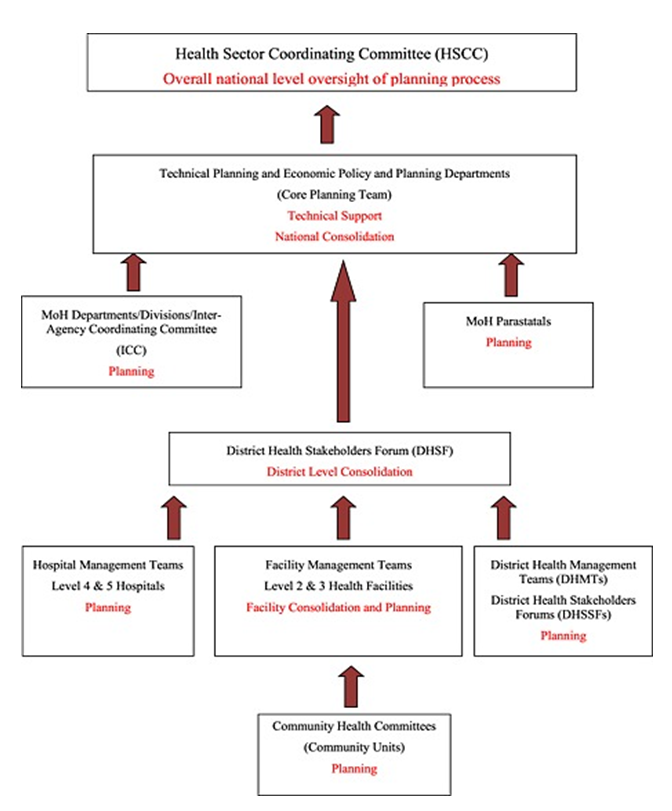

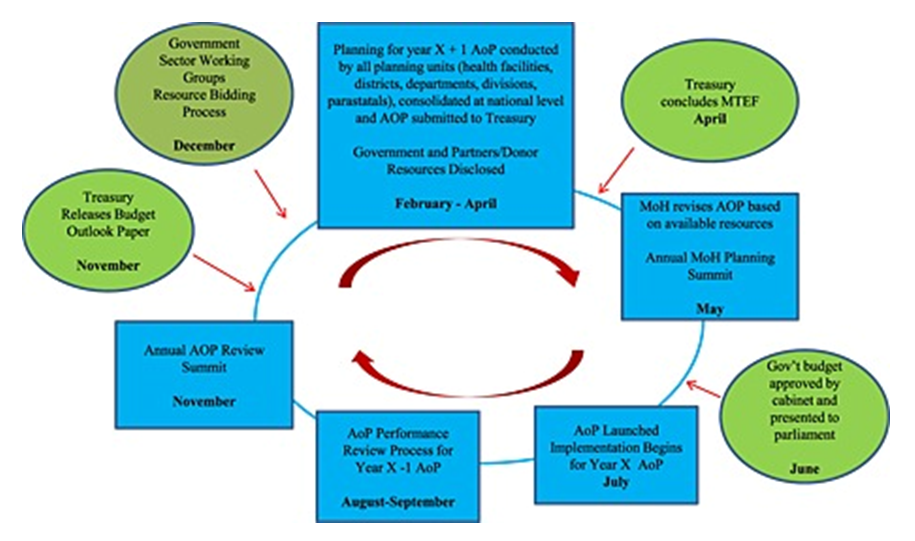

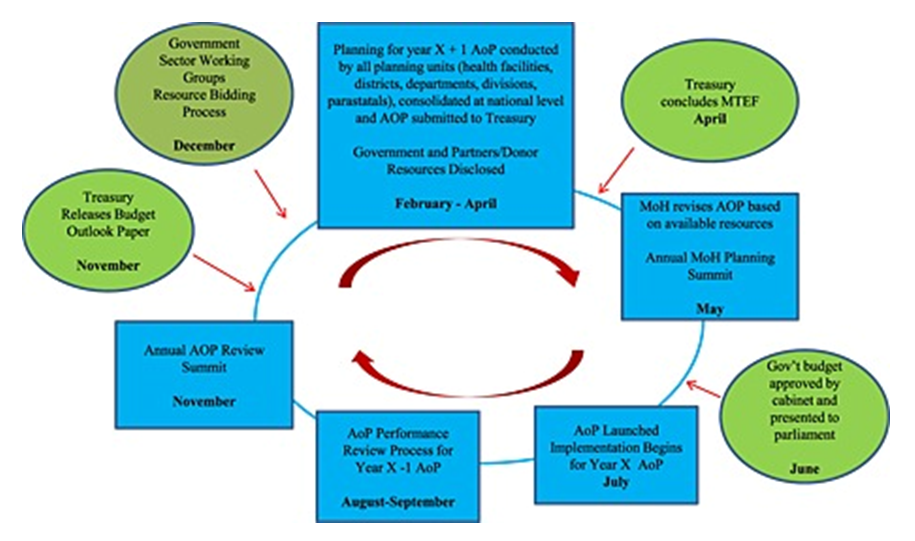

The development and implementation of Annual Operational Plans was initiated with the implementation of the NHSSP II in 2005. The Ministry of Health adopted the Annual Operational Plan (AOP) process in alignment with the MTEF, where year‐by-year AOP priority targets were set guided by the sector strategic objectives, the preceding year's sector performance, and available resources for the specific year. In the first year, a top-down approach was used as a way of setting up systems and frameworks for implementation of the NHSSP II objectives. There was limited input from technical service areas and other stakeholders of the sector. Tools and frameworks to initiate the bottom-up planning process were also developed and applied [11].The AOP 2 was developed, based on collation of information from different areas and stakeholders of the sector, with districts trained on the formulation of comprehensive plans, which were collated, and formed the basis for the service delivery targets. Despite these approaches, several challenges were met in planning at the sub-national level:• Not all health facilities participated in the process of planning, despite the efforts made to have a bottom-up planning approach starting with rural health facilities. The rural health facilities did not develop their plans and as such had no input into the district plans [12,13]. • Level 4-6 health facilities failed to plan due to the unsuitability of the planning formats for hospital planning [13]. • Inadequate training on planning as only two people from each district were trained for only a day [13]. • Late release of resource envelops to the planning units, thus misalignment of AOP with the budget and MTEF processes and structures, thus a huge gap between resources available and the AOP budget [13,14]. • Lack of mainstreaming of gender and human rights into the district health plans [13,15].Based on these lessons, the following principles drove subsequent planning processes [13]:• Planning formats were made available for community health services (level 1); rural health services (level 2-3); hospital services (L4-6); and for management support from the district, provincial, division, department, and parastatals with a format designed for each to increase focus on plans for each planning unit.• The bottom-up planning process was adopted, with interventions from each level informing priorities for the level above. A consolidation format and process were included in the planning format for each level of care above the community. • Further efforts were made to define the sector resource envelope before the commencement of the planning process. This process did not only capture Government and on budget resources, as defined in the MTEF, but also the off-budget resources available for delivery of the sector priorities.• Introduction of a cascading training pattern, where the national level trained the provinces, who trained their districts and who in turn trained their facilities. A standard planning guide, planning formats, and a facilitation manual were used, to ensure harmony. To improve ownership of the process, each level used resources they had available, as opposed to waiting for resources from the national level.• Formats and tools were provided to national-level programs that highlighted key service standards to guide planning for activities, targets, and priorities with funds that they needed a respective planning unit to consider.Figure 1 illustrates how the planning cycle was before devolution. The process started by reviewing the previous year's (x-1) AOP in August, where planning units prepared a short annual performance report. These reports were consolidated in a bottom‐up manner, into a national AOP performance report, that was presented to partners and stakeholders by September. This report formed the agenda for stakeholders' discussions at the November AOP review summit, where the sector identified the priorities for the coming year. This summit was planned to coincide with the treasury releasing the Budget Outlook Paper that elaborated on the respective sector budgetary ceilings.  | Figure 1. Planning Cycle Prior to Devolution |

Planning units began developing the AOP’s for the following year (x+1), in February, using a bottom-up approach, as illustrated in Figure 2. The MoH then submitted the consolidated ministry AOP through the Sector Working Group in April for funding consideration by the National Treasury. Upon finalization of the national budget process, the treasury communicated back to MoH, on the resources allocated. The MoH then revised its AOP based on resources confirmed by Treasury. In May, the MoH organized the annual planning summit where stakeholders met to discuss the work plan, which was launched in June to begin implementation in July, once Treasury presented the national budget to parliament [5]. | Figure 2. Planning Process prior to devolution (Source: Health sector operational planning and budgeting processes in Kenya— “never the twain shall meet”; The International Journal of Health Planning and Management) |

This process and cycle failed to meet the real needs of the populations since the cycle was not adhered to on most occasions leading to missed priorities. Common examples are the imbalance of resources between preventive care and curative care, between different social groups, between different regions or geographical areas, between staff salaries and medical supplies, or between different types of staff such as generalists and specialists.Since the establishment of County Governments in 2012, county health departments have taken lead in priority setting, planning and resource allocation (PSRA) in line with the functions prescribed under the fourth schedule of the constitution. Devolution has expanded decision making spaces concerning PSRA, with a new set of actors, for example, the county assembly, county executive; and new requirements that include preparation of the County Integrated Development Plans, program-based budgets, and sector working group reports. Planning and budgeting are now entrenched through several legal frameworks [16] [10] [17] that ensure synchrony between the two processes. The outcome of planning is conditioned by the behavior of individuals and groups at all levels in the process. This paper examines the health sector planning and budgeting processes at the county level, what has worked, challenges, and recommendations. These findings are relevant to health systems strengthening efforts within the health sector.

2. Methods

This was a qualitative study with data collected in 2019, primarily through participant observation, document review, and formal in‐depth interviews. Participant observation is a qualitative research method in which the researcher not only observes the research participants but also actively engages in the activities of the research participant. The researcher integrates into the participants' environment while also taking objective notes about what is going on [18]. Document review is a way of collecting data by reviewing existing documents including reports, program logs, performance ratings, funding proposals, meeting minutes, newsletters, and marketing materials [19]. Semi‐structured interviews employ a blend of closed- and open-ended questions, often characterized by follow-up why or how questions. It can meander around the topics on the agenda or delve into totally unforeseen issues [20].This study adopted a mixed-methods approach. The quantitative component of the analysis was based on data drawn from the Government of Kenya budget documents and the Integrated Financial Management Information System. We also implemented semi-structured interviews with 15 counties in the health sector. (Vihiga, Busia, Trans-Nzoia, Migori, Kisii, Nandi, Kakamega, Bomet, Kisumu, Nakuru, Turkana, Homabay, Baringo, Nyamira and Siaya Counties).

3. Results

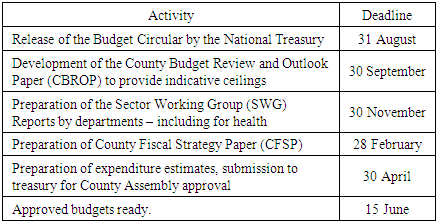

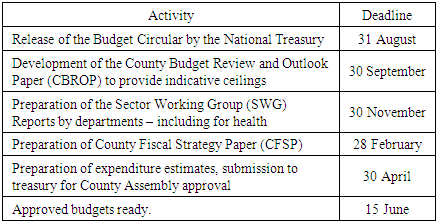

Planning at the county level is integrated with efforts of national and devolved government, and other relevant stakeholders coordinated at the local level. The planning framework integrates economic, social, environmental, legal, and spatial aspects of development to produce a plan that meets the needs and sets the targets for the benefit of local communities. The plans are aligned to national plans such as the Kenya Vision 2030, its Medium-Term Plans, and the National Spatial Plan as well as to international commitments such as the Sustainable Development Goals. The planning cycle post-devolution is as illustrated in Table 2 below:Table 2. Planning and Budgeting Cycle post Devolution

|

| |

|

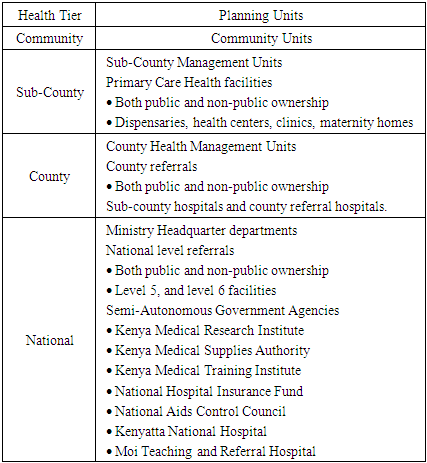

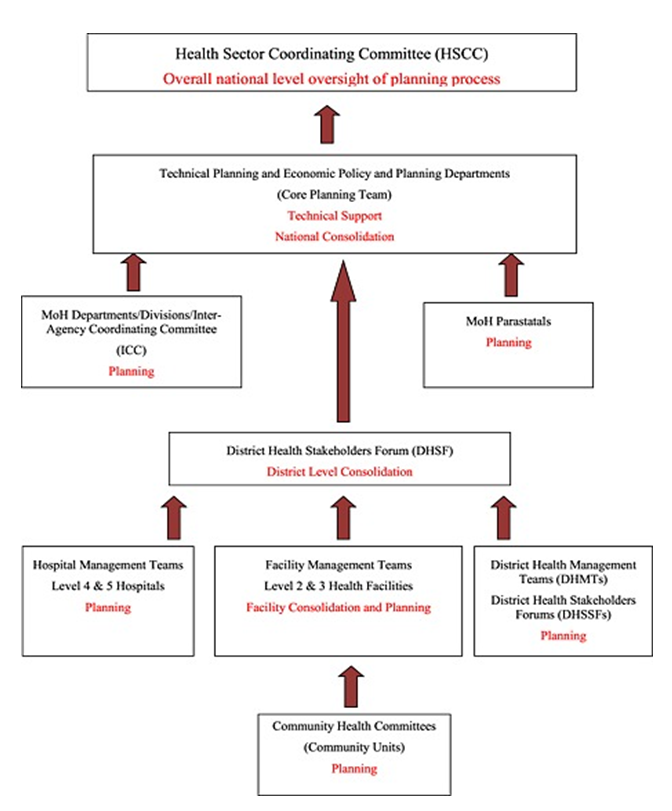

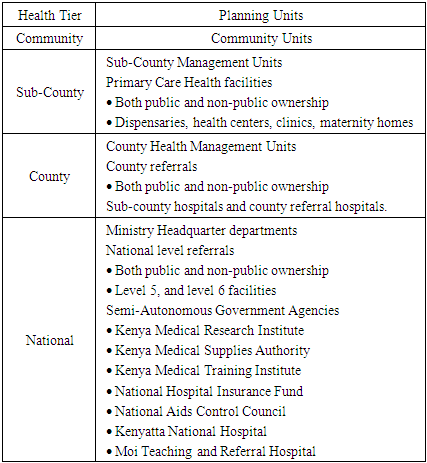

Table 3 describes the planning units at each level. It defines their targets to support a fully functional health system, prioritize the required investments across the seven health system building blocks and mobilize the resources required to meet its targets. Table 3. Health sector tiers and planning units

|

| |

|

Section 102(h) of the County Governments Act, 2012, mandates the county governments to provide a platform for unifying planning, budgeting, financing programs, implementation, and performance review. Section 108 requires county governments to prepare 5-year County Integrated Development Plans (CIDPs) and the annual county budgets to implement them. There is evidence of preparation of CIDPs as all of the 15 CIDPs (2018 – 2022) for the respective study sites are available at the Council of Governor's official website [21]. Planning and budgeting activities at the county level are guided by the CIDPs. They are effective documents as seen in the detailed review of the implementation of the 2013-2017 CIDPs provided in the 2018-2022 CIDPs. Moreover, 2018-2022 CIDPs are built on the successes of the first CIDPs (2013-2017) [22-35].In addition to CIDPs, the counties should to have the following: County Sectoral Plan (10 years); County Spatial Plan (10 years); and Cities and Urban Areas Plan (5 years) among other plans. While all the counties have County Sectoral plans in place, a review of the implementation of the 2013-2017 CIDPs shows that none of the counties had GIS-based County Spatial Plans within the period under review. Fortunately, the 2018-2022 CIDPs have included the development of spatial plans in their plans and budgets. There is also no evidence on the availability of the Cities and Urban Areas Plan in the CIDPs. Integrated Urban Development Plans (IUDP) are ideal tools for guiding strategic urban investments at the county level. Migori, Kisumu, Transnzoia (Kitale), Kakamega, Bomet (ongoing development), Nakuru (draft), Turkana (Lodwar), Homabay (municipality), Baringo (Kabarnet), Siaya (draft), Vihiga, and Busia counties have the Integrated Urban Development Plans available online. Among the 15 counties, only Vihiga, Busia, Trans-Nzoia, Nandi, Kakamega, Baringo, and Nyamira counties have published Annual Development Plans for 2019/20 online [36]. In all the counties, members of CDoH and stakeholders prepare the budget following the PFMA (2012) [37]. While section 104 (1) of the County Governments Act states that the county governments shall plan for the county and no public funds shall be appropriated without a planning framework [17], there is a provision for changes to be made to the budget through the supplementary budget. Counties can re-prioritize in line with funding realities. For example, among the 15 counties, Siaya County had projects implemented outside the 2013-17 CIDP due to the continuing and pressing needs of the public [35]. All the counties have a budget line for planning in the health department.Regarding partner supports for health sector supervision and auditing, all counties have guidelines and tools for supervision. Among the 15 counties, Transnzoia, Migori, Kisii, Kakamega, Nakuru, Homabay, Baringo, and Siaya counties had approved guidelines and tools for support supervision. The rest have drafts that are yet to be approved. The supportive guidelines should have a planning tool, a supervision checklist, a scoring mechanism, a structured report, and a feedback and action plan. Among the 15 counties, Vihiga, Trans-nzoia, Kisii, Bomet, Nakuru, Homabay, and Baringo counties' support supervision guidelines meet most of these criteria. Besides, during the last support supervision, Trans-nzoia, Kisii, Bomet, Nakuru, Homabay, Baringo, and Nyamira counties' complied with most of these guidelines compared to the rest that complied partly. Vihiga County did not comply at all. Among the 15 counties, only Turkana and Homabay counties did not receive external technical support towards the development of these guidelines. While Homabay and Migori counties developed these guidelines with the greatest financial support from the government, Turkana and Kakamega counties did not receive any financial report. The rest of the counties received partial financial support from the government of Kenya.A review of the implementation of the previous CIDPs shows improvement from the baselines indicators in all counties. The health sector promoted IT innovation in various facilities by installing IT software (Electronic Medical Records for HIV/AIDS). County health infrastructure also received facelifts within the period under review. There is also evidence of staff training, performance contracting, annual planning, and performance review undertaken within these counties. The baselines are used in developing planning documents including CIDPs and health sector strategic plans [22-35].The plans are bottom-up, from the health facilities upwards, and the process is consultative in all counties. The county government leadership, development and implementing partners, and other stakeholders participate in the development of the health sector strategic and investment plans. Members of staff from the department of economic planning also participate in planning. Some are domiciled within the department where they are involved in fiscal and macro-fiscal policy management, preparation of the CIDPs, management of financial resources, management of the county tax policy, and ensure effective use of government revenue. They coordinate the public and private sector activities and facilitate the private sector for economic development. They also coordinate with international agencies and mobilize resources ensuring effective use, management, accounting, and monitor functions of the county development priorities. Unfortunately, there is no standard definition and measure as to what comprises effective participation. High attendance rates may not necessarily be representative in terms of area distribution and demography (age, gender, special interest groups) resulting in poor ownership of the projects. Performance contracting has been cascaded from the CECM to the lower level officer. The county CIDPS have a monitoring and evaluation framework that provides for quarterly and annual reports to assess the progress made in implementing the CIDPs, and providing necessary information and feedback. At all levels, performance review reports should be produced outlining the performance against the outlined strategic objectives. The annual performance reviews of the AWPs and end-term review of the County Strategic and Investment Plans are used to input into the next plans [22-35].Regarding coordination with the planning and legal unit, the Kenyan legislative framework establishes various bodies to coordinate and supports the CIDP implementation processes. Key among them is the County Economic and Budget Forum (CBEF) that brings together the County Executive Committee; community representatives from women, youth, and persons living with disabilities, civil society, elderly persons, the private sector, and professional associations. During the implementation period, CBEF provides advice on development priorities in budgets, prepare budget statements, advise the executive on strategic investments, and represent the community aspirations.

4. Discussion

The finding of this study captures the progress made in county planning for the counties under review. There is evidence of the development and implementation of CIDPs and other county development plans against a backdrop of challenges. The main challenges experienced are summarized below.

5. Challenges

Several challenges are faced at the county level that hampers smooth planning. There is a lack of adoption and adaptation of national-level legal instruments and policies. This is caused by failure to factor legislation costs when developing or domesticating some policies. Inadequate resources to undertake the planning due to either erratic funding for planning or an overreliance on health partners to fund planning activities also hampers planning. Political interference by the legislative assembly on priority setting and failure to embrace the relevance of health planning the executive and political wing are also obstacles to planning.There is sometimes a lack of political goodwill as engaging with MCAs has also been cited as a problem when it comes to planning for health. There is a lack of an interface between the standard AWP template and the facility template which causes information provided by the facility not to be in line with the AWP. Due to a lack of transparency at the leadership level, officers at the county level are forced to plan without complete information from seniors.Technocrats get discouraged by the lack of outcomes from planning. Public participation is a requirement in the planning process, but many counties have weak structures that lock out beneficiaries that would otherwise contribute to the process. Moreover, those who are required to mobilize the community do not do so.There is poor implementation of the plans by the counties mainly due to poor disbursements of funds to facilitate both the planning process and the implementation of the planned activities. Missing information regarding partner resource envelopes denies counties the chance to plan fully with all funding sources. Moreover, some health partners disclose their resource envelope too late to be included in the AWP. Eventually, there is a disconnect between health partner support with the budget and planning office. This all stems from the fact that many counties neither have a partner coordination framework nor signed an MOU which would require the health partners to disclose their resource envelopes. There is also no meaningful involvement of stakeholders as their presence is mainly to comply with the law but there is a lack of policy and guidelines on how to actively involve all stakeholders during the planning process. This results in poor coordination, weak communication channels, weak inter-sectoral collaboration, lack of regular TWG engagements and this is if the TWG exists, lack of regular interactive forums, weak participation in the budget by the planning office as well a lack of transparency in county planning information data. A lack of an advocacy, communication and mobilization strategy for the planning process adds to this challenge.Most health sector working groups within the counties do not exist and if they do, are not fully operational. These groups are an integral part within the planning process and if they are lacking, the effects are felt due to poor planning. There is non-adherence to the planning cycle as counties commence the planning process erroneously with determining the budget estimates, a stage that should follow after completing the development of the CIDP, ADP and AWP. Once plans have been prepared the counties are also faced with poor dissemination of final plans. Most often, the plans are often developed late. This results in there being a short time frame in properly developing all relevant documents. Counties have weak M & E structures and frameworks that would allow them to assess their planning processes including financial appraisals of plans. This is due to the fact that many CDoH do not have an M & E unit within. There is not only inadequate HRH for planning in the health sector with limited technical skills, but also high staff turn-over of the few officers within planning units. There is a weak linkage between the planning and budgeting process of the health sector.

6. Recommendations

The planning process in the CDoH should involve a sufficient number of staff members/officers. Moreover, there should be regular capacity building initiatives for the officers on planning tools. These will promote skills accumulation, transparency in the process and eventual fiscal disciple during implementation. For efficiency purposes, certain planning documents should be merged for instance the CIDP and the ADP or the MTEF and the AWP. There should also be timely communication on planning processes to all involved. Resource mobilization efforts for the planning process should be conducted beforehand to ensure sufficient funds are available. Moreover, the information should be available to enable the process to proceed smoothly. This could be supported through data mining, analysis, and presentation of the information needed.Efforts in targeted advocacy towards influential people who can influence for instance chairpersons of committees of county assemblies should be increased. Moreover, awareness among the public should be increased and this can be achieved through actively engaging the civil societies. Moreover enforcing or domesticating a public participation policy would greatly support. Proper sensitization of stakeholders on the planning process and the associated timelines should be implemented. Structured public participation engagements should be implemented by the CDoH to enable the inclusion of the beneficiaries’ voices. County administration structures should be cascaded to ward and village levels to enable participation at all levels. Moreover, all administration practices should be enforced to ensure adherence during the planning process of the department.Inter-sectoral linkages should be strengthened by deploying an economist to work across all three sectors and the private sector. All activities related to the Health Sector Working Group should be budgeted for so that they get well funded to achieve their objectives. This extends to the whole planning process as a sufficient budgetary allocation reduces reliance on partners. Functional TWGs should also be constituted and meet regularly. County and National calendars should be harmonized for seamless planning and implementation across the whole health sector. A partner coordinating framework should be developed and implemented. All health partners working in the county should disclose their resource envelope promptly to enable its inclusion in the AWP. Moreover, the health partners' planning process should be integrated with the department’s planning cycle to promote synergies. Finally, the CDoH should establish and operationalize functional M&E units whose functions contribute towards planning. Each program officer should be trained on the core M&E components including DHIS2. There is a need to undertake regular and comprehensive support supervision and mentorship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the budgeting teams from Vihiga, Busia, Trans-Nzoia, Migori, Kisii, Nandi, Kakamega, Bomet, Kisumu, Nakuru, Turkana, Homabay, Baringo, Nyamira and Siaya Counties.

References

| [1] | Kenya Vision 2030 | Kenya Vision 2030 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://vision2030.go.ke/. |

| [2] | Kenya Law: The Constitution of Kenya [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 22]. Available from: http://kenyalaw.org/kl/index.php?id=398. |

| [3] | Universal Health Coverage | The Presidency [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 4]. Available from: https://www.president.go.ke/universal-health-coverage/. |

| [4] | 10 of 1965 on African socialism and its application to planning in Kenya The | Course Hero [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: http://suo.im/6gyOVN. |

| [5] | Tsofa B, Molyneux S, Goodman C. Health sector operational planning and budgeting processes in Kenya-"never the twain shall meet". Int J Health Plann Manage [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Mar 12]; 31(3): 260–76. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/hpm.2286. |

| [6] | Health sector planning and budgeting in Kenya: recommendations to improve alignment | RESYST [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: http://suo.im/62cMnn. |

| [7] | Budgeting at the County Level in Kenya: What has Worked, Challenges and Recommendations [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: http://article.sapub.org/10.5923.j.phr.20201002.03.html. |

| [8] | Ochanda P. The Impact of Medium Term Expenditure Framework on Operational Efficiency of Government Ministries in Kenya. 6225. |

| [9] | GoK. (1965). Sessional Paper No. 10 on African Socialism and Its Application to Planning in Kenya. Government Printer. Nairobi. [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: http://www.sciepub.com/reference/249938. |

| [10] | Ministry of Health. Kenya Health Policy Framework (KHPF). 1994-2010. 1994. |

| [11] | The Second National Health Sector Strategic Plan of Kenya - Health Publications [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: http://publications.universalhealth2030.org/ref/6cbfa6baf218b1e7ee9d3302fc5359ff. |

| [12] | Nzuki H, Ombuki C, Arasa R. Challenges Affecting Implementation of Strategic Plan in Kenya Health Sector; A Case of Public Hospitals in Machakaos County. Noble Int J Soc Sci Res. 2017; 2(10): 95–107. |

| [13] | Health Rights Today [2] Edition 10. |

| [14] | Challenges of the Devolved Health Sector in Kenya: Teething Problems or Systemic Contradictions? | Africa Development [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ad/article/view/163620. |

| [15] | Newman C. Time to address gender discrimination and inequality in the health workforce [Internet]. Vol. 12, Human Resources for Health. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2014 [cited 2020 May 28]. p. 25. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4491-12-25. |

| [16] | Kenya Law: The Constitution of Kenya [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 25]. Available from: http://kenyalaw.org/kl/index.php?id=398. |

| [17] | The County Governments Act, 2012 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from: moz-extension://0410c391-9c72-49e8-b3de-8b7abd2b83e2/enhanced-reader.html? openApp&pdf=http%3A%2F%2Fkenyachamber.co.ke%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads %2F2017%2F02%2FThe-County-Government-Act-2012.pdf. |

| [18] | Kothari CR. Research methodology: methods and techniques (New Age International). 2004. |

| [19] | Rohwer A, Schoonees A, Young T. Methods used and lessons learnt in conducting document reviews of medical and allied health curricula - a key step in curriculum evaluation. Vol. 14, BMC Medical Education. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2014. |

| [20] | Adams WC. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In: Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation: Fourth Edition. Wiley Blackwell; 2015. p. 492–505. |

| [21] | CoG Reports [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: http://cog.go.ke/cog-reports/category/106-county-integrated-development-plans-2018-2022. |

| [22] | Vihiga County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP). |

| [23] | Busia County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP). |

| [24] | Transnzoia County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP). |

| [25] | County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP) 2018-2022 – County Government of Kakamega [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: https://kakamega.go.ke/public-participation-county-development-plans/. |

| [26] | County Government of Bomet County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022. 2018. |

| [27] | Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP) 2018-2022. 2018. |

| [28] | Republic of Kenya Homabaycounty Government Second County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022 (Draft). |

| [29] | Republic of Kenya Baringo County Government County Integrated Development Plan. 2018. |

| [30] | Nakuru County Integrated Development Plan (2018-2022). |

| [31] | County Government of Nyamira County Integrated Development Plan (2018-2023). |

| [32] | County Government of Nandi County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2023. |

| [33] | County Government of Migori County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022. |

| [34] | Kisii County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP). |

| [35] | Siaya County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP). |

| [36] | Kenya County Budget Transparency | IBP Kenya [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: http://suo.im/5NamPf. |

| [37] | The Public Finance Management Act, 2012 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 12]. Available from: http://crecokenya.org/new/index.php/resource-center/bills/177-the-public-finance-management-act-2012. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML