-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2020; 10(2): 78-86

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20201002.06

Measuring the Extent of Compliance to Standard Operating Procedures for Documentation of Medical Records by Healthcare Workers in Kenya

David F. O. Omoit , George O. Otieno , Kenneth K. Rucha

Department of Health Management and Informatics, School of Public Health and Applied Human Sciences, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: David F. O. Omoit , Department of Health Management and Informatics, School of Public Health and Applied Human Sciences, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

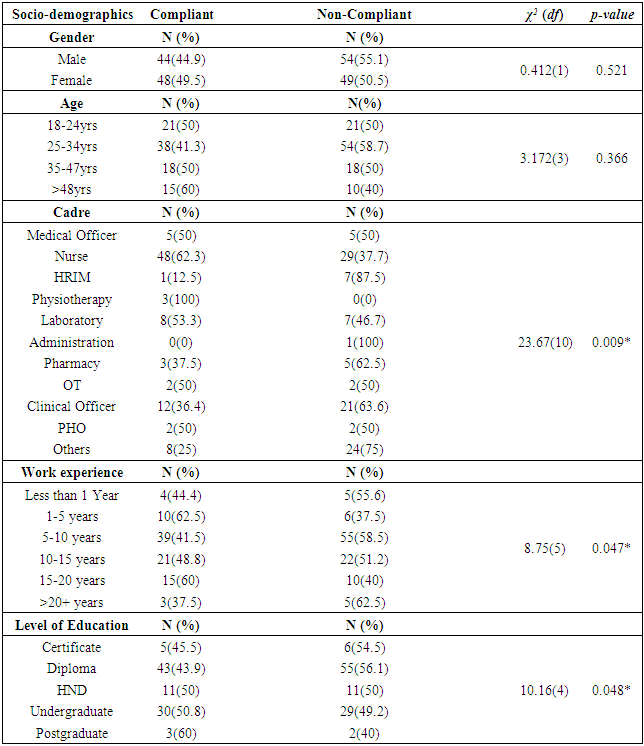

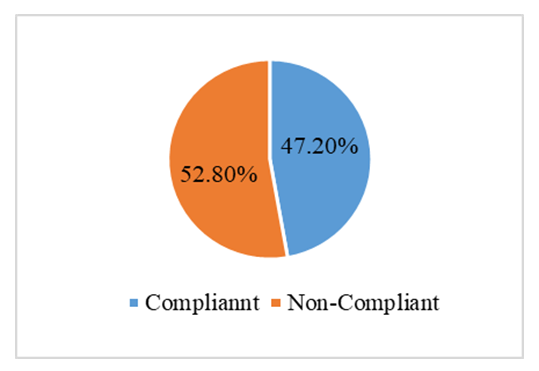

Poor compliance to health systems guidelines and standards are associated with a dismal performance and it contributes greatly, to high number of deaths, injury, medical errors, patients harm and ineffective care. Globally, patient harm is the 14th leading cause of disease burden. The study sought to establish the compliance to standard operating procedure (SOP) for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers, Kenya. In particular, the current study leveraged a descriptive cross-sectional methodology to determine the association between socio-demographic characteristics and compliance to SOP for documentation of medical records among 197 healthcare workers sampled from 400 healthcare workers in Bungoma level 4 hospital. Stratified proportionate and simple random sampling techniques were employed. Quantitative data was collected using self-administered questionnaires. Informed consent was nevertheless obtained from all respondents prior to the study. Moreover, data management was made possible using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. On the other hand, Chi square analysis was used to test the association between dependent and independent variables, albeit at 95% confidence interval (CI). Frequency tables and pie charts were used to present the results. More importantly, the initial Chi square analysis revealed, a strong association between cadre χ2 (23.67, df=10, N=195) p=0.009, work experience χ2 (8.75, df=5, N=195) p=0.047, and level of education χ2 (10.16, df=4, N=195) p=0.048, even though the association between gender (χ2=0.412, df=1, N=195) p=0.521 and age (χ2=3.172, df=3, N=195) p=0.366 were not significant. The current analysis has confirmed the compliance level was very low at 47.2%. The immediate implication is that the county health management team needs to foster continuous in-service training and refresher courses to strengthen healthcare worker’s skills in compliance with the SOP for documentation of medical records. Future research should otherwise consider looking at the influence of institutional characteristics on healthcare worker’s compliance to SOPs for documentation of medical records in Bungoma level 4 hospital and beyond.

Keywords: Compliance, Documentation, Healthcare Workers, Medical Records, Standard Operating Procedure (SOP)

Cite this paper: David F. O. Omoit , George O. Otieno , Kenneth K. Rucha , Measuring the Extent of Compliance to Standard Operating Procedures for Documentation of Medical Records by Healthcare Workers in Kenya, Public Health Research, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 78-86. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20201002.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A standard operating procedure (SOP) is a guideline that documents a routine or repetitive activity followed by an institution. The development and use of standard operating procedures are an intrinsic part of a successful quality system as it provides individuals with the information to perform a job properly, and facilitates consistency in the quality and integrity of a product or end-result (Akyar, 2012).On the other hand, the medical record is a means of communication among the physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals who plan and conduct the care and treatment of the individual patient (Bowman, 2013). Medical records have been defined as the collection of information concerning patient health status that is created around time admitted (Lekha, 2017). The medical record may be paper or electronic or both (hybrid). Creation, content, maintenance, management, processing, and expected quality measures must be standardized, hence compliance to these standards requires concerted efforts from the allied healthcare workers (Abdelhak et al., 2014). The long-term care facility employees who work with electronic health records systems daily were positive about their experiences. In that, they gained much confidence in handling data and giving accurate information. In particular, operational improvements were achieved through increased access to resident information, cost avoidance, increased documentation accuracy, and implementation of evidence-based practices per cadre (Cherry, Ford, & Peterson, 2011).More importantly, health is an essential sector in the economy. The country with weak health systems and guidelines is bound to experience poor productivity. Despite the role played by the health sector, they still experience severe problems in the documentation. Documentation in healthcare records must describe each patient/client's contact with a healthcare worker. The policy requires that a healthcare record is available for every patient/client. It will assist with assessment and treatment, continuity of care, clinical handover, patient safety, and clinical quality, education, research, evaluation, medico-legal, funding, and statutory requirements that require medical records (Chebole, 2015). Illegibility of the medical records needs to be standardized to capture point of view regarding the patient facts even if the patient is in new admission. There is a need to make clear policies to avoid the wrong administration of medication. It can be achieved by conducting regular training of staff on documentations (Walsh & Dougherty, 2012).Education and work experience of health workers, on the other hand, has a substantial association with standard operating procedures in improved service delivery. The results indicated that providing adequate skills across different cadres will improve documentation is an important socio-demographic factor that can affect compliance with the standard operating procedures for documentation of Medical records. This means that equipping staff with relevant skills and knowledge may have a greater role in influencing proper documentation of medical records and data quality (Tims, 2013). Moreover, previous studies have determined that the overall quality of data of electronic medical records doesn’t differ with gender roles assigned (Hamm, Kamin, Chipperfield, Perry, & Lang, 2019). In accumulation, the work of an experienced population in terms of age and gender influenced precise products. As a result, demographic factors such as literacy levels provide clarification on the total population of the healthcare worker in a health facility in those people who are expected to adhere to standard operating procedures for health documentation and those who are not to adhere to the standards. The overall change in the number of Healthcare Worker in the documentation facility influences the compliance to the Standard operating procedures of patient’s medical records. The group of healthcare worker by demographic characteristics had also significant changes in compliance with documentation standards (Ahwidy & Pemberton, 2016).Even though globally, there is still a high use of paper-based systems accounting for 31% of responding countries ranking its deployment level as “very high” (Kolch, 2013). In the health care situation, the main responsibility of the healthcare worker is to comply to standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records. When healthcare workers do not comply to the guidelines, this may reflect a lack of knowledge of guidelines or a lack of compliance regardless of knowledge which eventually leads to deaths, injury, medical errors, patient harm and ineffective care (Das et al., 2012). The effectiveness of care can be assessed using inspection of medical records, patient exit interviews, direct observation of provider-client interactions, standardized patients or clinical vignettes (Das et al., 2012). Patient harm is the 14th leading cause to the global disease burden. The majority of this burden falls on low and middle-income countries (Slawomirski, Auraaen, & Klazinga, 2017). Over 210,000 people in USA die annually due medical errors (James, 2013). Updates on medical record management systems indicate that there is a need to update automated systems to minimize medical errors (James, 2013). According to the Association (2018), Only 5% of responding countries reported using the standard operating procedure for documentation for their data. Yet, there are deficiencies in record-keeping practices such as duplication, incomplete data, and data inaccuracies that have been reported at primary health care level in the public health sector in South Africa. Such deficiencies have the potential to impact patient health outcomes as the break-in information negatively may hinder the continuity of care (Sani, Ibrahim, Ango, Hussaini, & Saleh, 2016; Mahomed, Naidoo, Asmall, & Taylor, 2015).Nevertheless, regarding hospital mortality, there is no reliable data on cause of death in Kenya, with less than 7% health facility reporting (Karuri, Waiganjo, Daniel, & Manya, 2014). The health record management practice is imperative to health service (Chebole, 2015). One of the key challenges in the Kenyan health sector identified in First Medium Term Plan of Vision 2030 document is weak health information systems. Over the years, data discrepancy in Bungoma level 4 hospital has been on the rise due to lack of compliance to the standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records. In particular, Facility based maternal mortality ratio at the Bungoma level 4 hospital in 2017 was 340.1 per 100,000 compared to National 116.2 per 100,000 and infant mortality 244.3/1000 compared to National 92.3/1000 in 2016 (Sukiatun, 2017). More importantly, the hospital was previously fined 2.5 million shillings due to gross medical errors in record keeping, which could have been avoided if the healthcare workers had complied to standard operating procedure (Odallo, Opondo, & Onyango., 2018). Nevertheless, Medical recordkeeping is indeed essential to assuring quality health care, even though, best practices in Medical recordkeeping is often inadequate in resource-limited settings, which threatens the quality of health care (Pirkle, Dumont, & Zunzunegui, 2012). Moreover, the significance of medical records in any given hospital cannot be over-emphasized, since they are the primary tool that can be used to achieve the maximum objectives and they are both valuable to the patients and the medical personnel. Medical records are thus a vital asset in ensuring that hospitals are run effectively and efficiently, as they support clinical decision-making, provide evidence of policies and support the hospitals in cases of litigation. Few studies have been done in Kenya to measure the association between demographic variables to compliance of SOP for documentation of medical records, yet to date, no known studies have been conducted in Bungoma county to measure the level of compliance to standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records.In summary poor documentation and non-compliance to the set guidelines and standards for documentation, has significantly contributed to high mortality, morbidity cases, and the increased average length of stay in the hospitals (Sukiatun, 2017).

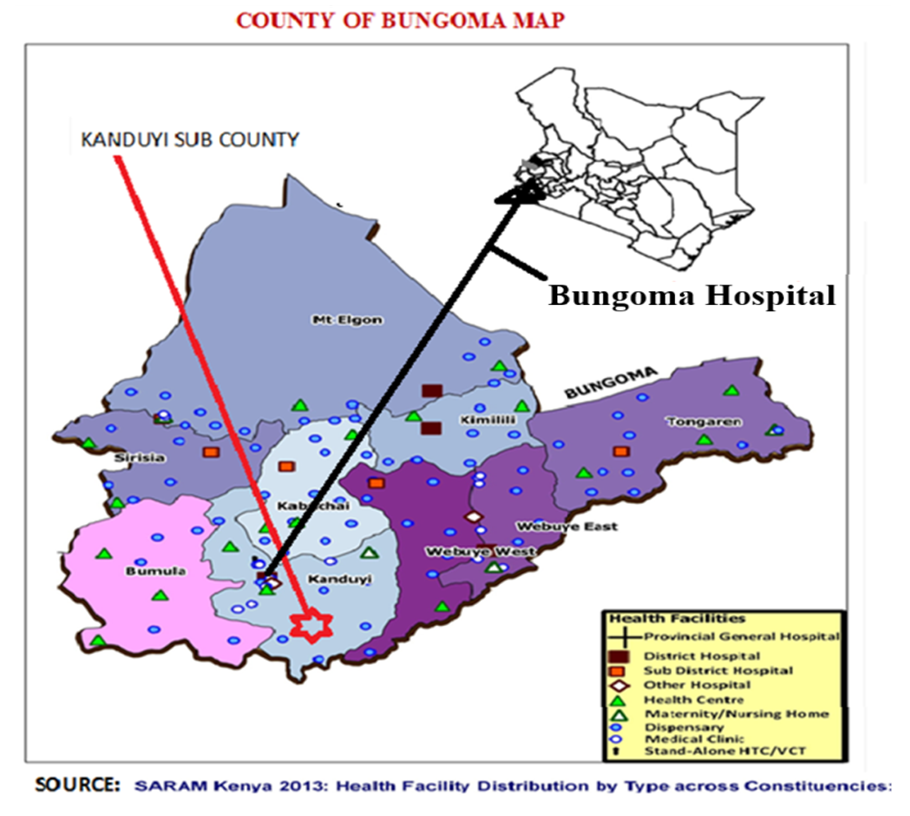

2. Materials, Methods

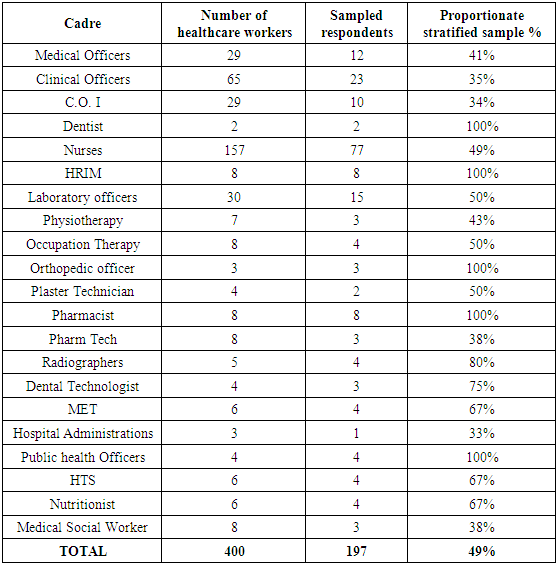

- Study designA cross-sectional descriptive research design was used. The basic idea behind the methodology was to measure the extent of compliance to SOP for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers. The selected variables age, gender, level of education, and work experience were used to get responses by asking respondents questions followed by an examination of variables. Study AreaBungoma is one of the four counties in the western region of Kenya. It has a land surface area of approximately 3,023.9 km2. It approximately lies between latitude 0°33'59.99" N and longitude 34°33'59.99" E. The county consists of nine sub-counties and forty-five wards. Kimilili, Kabuchai, and Webuye west have four wards each; Mt Elgon and Tongareni have six wards each; Sirisia and Webuye east have three wards each; Kanduyi and Bumula have 8 and 7 wards each respectively. It has a population of 1,670,570 of which 812,146 are males 858,389 females as per the 2019 census (KNBS, 2019). The major economic activities are maize farming, sugarcane plantation, tobacco, onions, vegetables, and dairy farming. Moreover, Bungoma county has 245 health facilities with 20 levels 4 hospitals, 131 dispensaries, 27 health centres, and 67 medical clinics as of 2020 (Karuri, et al., 2014). The most prevalent diseases in the county are malaria, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections (URTI), worms, and diarrhea. Bungoma level 4 hospital It’s located in Kanduyi sub-county; it borders Kabuchai to the North, Webuye west to the east, Kakamega north to the southeast, Sirisia to the west and Bumula to the south. It covers an area of 318.5 km2 and its a referral hospital for Bungoma county. The facility's catchment population is 108,261 with 52,073 males and 56,187 females. The doctor population ratio is 0.2 per 10,000 populations, clinical officer ratio is 2.1 per 10,000, and nurse’s ratio 3.2 per 10,000 populations.

| Figure 1. Map of Bungoma county showing the location of Bungoma level 4 hospital |

|

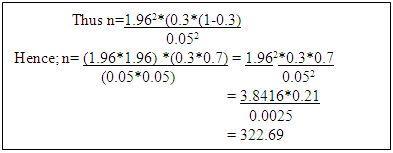

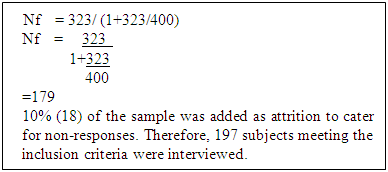

Since the population estimate is less than 10,000 which is 400, Fishers et al second correction formula will be used;nf = n/(1+n/N)where; nf= New sample sizen=desired sample size calculated using the first formulaN=Population estimate

Since the population estimate is less than 10,000 which is 400, Fishers et al second correction formula will be used;nf = n/(1+n/N)where; nf= New sample sizen=desired sample size calculated using the first formulaN=Population estimate VariablesIndependent variables; were the demographic characteristics (age, gender, level of education and work experience).Dependent variables; was the extent of compliance to the standard operating procedures for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers (compliant and non-compliant).Exclusion criteria; the study excluded healthcare workers who were away on leave or any other healthcare worker who was unwilling to participate in the study.Inclusion criteria; the study included all Bungoma level 4 hospital healthcare workers both day and night duties.Construction of research instruments; closed-ended questionnaires were used to collect quantitative data from the respondents. The questionnaires were administered by the researcher and research assistants.Pilot study or pre-testing ValidityA pre-test study was conducted to test the validity of the instruments to be used where 10% of the sampled population was used in the test. After the issue of 10% of the questionnaires for the test, the validity of the instrument is the extent to which it does measure what it is supposed to measure. Validity is the accuracy and meaningfulness of inferences, which were based on the research results. It is the degree to which results obtained from the analysis of the data represent the variables of the study (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). Validity was done by two research assistants who were trained before data collection to ensure they collect the desired data. The researcher accompanied the assistants on different days to ensure accuracy.Few changes were made during pre-testing which included reducing the number and length of the study tools to minimize the time required to complete an interview, besides, to enhance the logical flow of questions and answers and revision of questions that were not clear to the respondents.Reliability.The reliability of an instrument is the degree of consistency with which it measures a variable (Van Teijlingen and Hundley, 2010). The research instrument was pilot tested to check its reliability. Cronbach’s alpha was used where any value of more than 0.5 indicated that the instrument was reliable and gives good internal consistency during the study. The method was ideal for the study because it required a single administration of a test and was the most appropriate type of reliability for measures that contains a range of possible answers for each item of an instrument. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.8, which indicated that the instrument was reliable. Test re-test technique was used to test for reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was used to interview twenty key informants after which the responses were compared and analyzed to check for consistency in responses. The questions were revised to enhance the consistency of responses. A re-test with twenty more respondents yielded consistent results. The revised questionnaire was used to conduct interviews and ensure the reliability of results.Data collection techniquesThe study used a semi-structured questionnaire to collect primary data from the respondents, and all the questionnaires were collected back and sought clarifications in case of any problems. The researcher checked the filled questionnaire for completeness and made a follow up to ensure all questions were appropriately answered. The researcher removed corrupt, incomplete, irrelevant, or inaccurate records from the database by cleaning the data. The researcher discarded any invalid questionnaire. Once questionnaires are completed the data collected was systematically arranged according to the codes of the questions to facilitate analysis. The data was stored on a computer. A password was used to secure the database while the questionnaires were locked in a cabinet at the Health records department office.Data analysis and presentationData were analyzed with the aid of the statistic package for social sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 in conjunction with the computer Microsoft Excel program. Quantitative data, descriptive statistics including frequency tables of gender, age, level of education, cadre, and work experience and the pie chart were used to summarize and describe the study sample and study variables. Chi square analysis was used to test the association between gender, age, level of education, work experience, cadre and compliance to SOP for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers, albeit at 95% confidence interval (CI). Frequency tables and pie chart were used to present the results.Ethical considerationThe study protocol was approved by the Kenyatta University ethical review board in close collaboration with the National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) and the Bungoma County Government, Ministry of Education and Health Department.

VariablesIndependent variables; were the demographic characteristics (age, gender, level of education and work experience).Dependent variables; was the extent of compliance to the standard operating procedures for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers (compliant and non-compliant).Exclusion criteria; the study excluded healthcare workers who were away on leave or any other healthcare worker who was unwilling to participate in the study.Inclusion criteria; the study included all Bungoma level 4 hospital healthcare workers both day and night duties.Construction of research instruments; closed-ended questionnaires were used to collect quantitative data from the respondents. The questionnaires were administered by the researcher and research assistants.Pilot study or pre-testing ValidityA pre-test study was conducted to test the validity of the instruments to be used where 10% of the sampled population was used in the test. After the issue of 10% of the questionnaires for the test, the validity of the instrument is the extent to which it does measure what it is supposed to measure. Validity is the accuracy and meaningfulness of inferences, which were based on the research results. It is the degree to which results obtained from the analysis of the data represent the variables of the study (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). Validity was done by two research assistants who were trained before data collection to ensure they collect the desired data. The researcher accompanied the assistants on different days to ensure accuracy.Few changes were made during pre-testing which included reducing the number and length of the study tools to minimize the time required to complete an interview, besides, to enhance the logical flow of questions and answers and revision of questions that were not clear to the respondents.Reliability.The reliability of an instrument is the degree of consistency with which it measures a variable (Van Teijlingen and Hundley, 2010). The research instrument was pilot tested to check its reliability. Cronbach’s alpha was used where any value of more than 0.5 indicated that the instrument was reliable and gives good internal consistency during the study. The method was ideal for the study because it required a single administration of a test and was the most appropriate type of reliability for measures that contains a range of possible answers for each item of an instrument. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.8, which indicated that the instrument was reliable. Test re-test technique was used to test for reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was used to interview twenty key informants after which the responses were compared and analyzed to check for consistency in responses. The questions were revised to enhance the consistency of responses. A re-test with twenty more respondents yielded consistent results. The revised questionnaire was used to conduct interviews and ensure the reliability of results.Data collection techniquesThe study used a semi-structured questionnaire to collect primary data from the respondents, and all the questionnaires were collected back and sought clarifications in case of any problems. The researcher checked the filled questionnaire for completeness and made a follow up to ensure all questions were appropriately answered. The researcher removed corrupt, incomplete, irrelevant, or inaccurate records from the database by cleaning the data. The researcher discarded any invalid questionnaire. Once questionnaires are completed the data collected was systematically arranged according to the codes of the questions to facilitate analysis. The data was stored on a computer. A password was used to secure the database while the questionnaires were locked in a cabinet at the Health records department office.Data analysis and presentationData were analyzed with the aid of the statistic package for social sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 in conjunction with the computer Microsoft Excel program. Quantitative data, descriptive statistics including frequency tables of gender, age, level of education, cadre, and work experience and the pie chart were used to summarize and describe the study sample and study variables. Chi square analysis was used to test the association between gender, age, level of education, work experience, cadre and compliance to SOP for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers, albeit at 95% confidence interval (CI). Frequency tables and pie chart were used to present the results.Ethical considerationThe study protocol was approved by the Kenyatta University ethical review board in close collaboration with the National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) and the Bungoma County Government, Ministry of Education and Health Department.3. Results

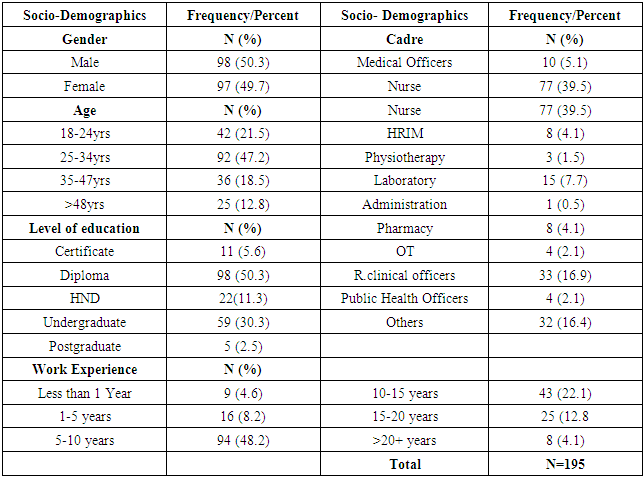

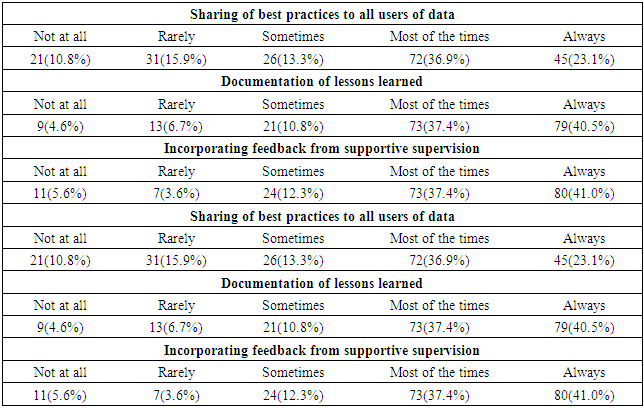

- Table 3.1 illustrates the social demographic characteristics of respondents. There were more males 98(50.3%) than the females’ respondent 97(49.7%). Close to half 92(47.2%) of participants in the survey aged between 25-34 years old. A fifth 42(21.5%) aged 18-24 years old, 36(18.5%) aged between 35-47 years old, while only 25(12.8%) aged above 48 years old. The majority 77(39.5%) of research participants were Nurses, 33(16.9%) were registered, clinical officers. other cadres accounted for 33(16.4%), while less than 1(1%) were in administration. Subsequently, 94(48.2%) of participants had work experience of between five and ten years at the time of data collection. 9(4.6%) of respondents had worked for less than 12 months, while 8(4.1%) had worked for over 20 years. With regard to the level of Education, more than half of the respondents 98(50.3%) in the survey had a diploma level of education. 59(30.3%) had a bachelors’ level of education. Certificate level and post-graduate holders accounted for 11(5.6%) and 5(2.5%) of all participants, respectively.

|

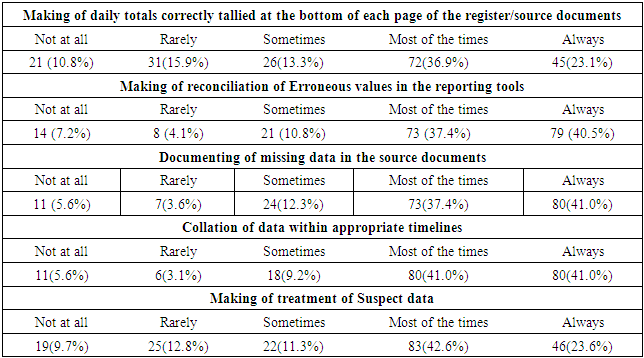

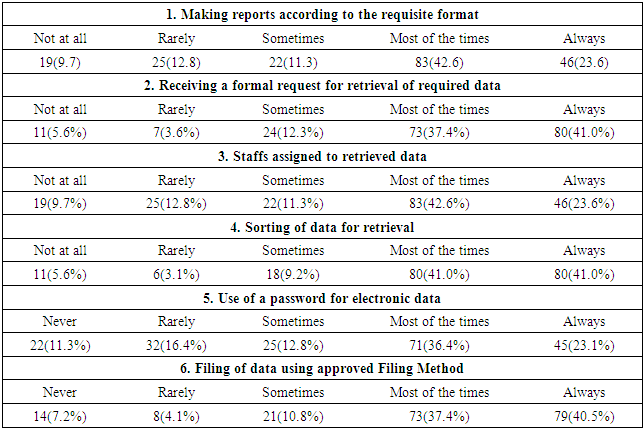

| Figure 3.1. Extent of compliance to S.O.P |

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The study finding indicated that half (50.3%) of respondents were male which implies gender equality of the respondent was considered in the study. Similarly, most of the healthcare workers at Bungoma level 4 hospital were aged between 25-34 years old thereby, indicating that the healthcare workers are young and energetic enough to deal with issues of compliance to standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records. In addition, majority of research respondents were Nurses, and Registered clinical officers. Furthermore, most of the healthcare workers at Bungoma level 4 hospital have worked for between five and ten years in the facility and therefore are well vast with the operations of the facility and the compliance to standard operating procedures for documentation of medical records. This was in agreement with Tims (2013), Education and work experience of healthcare workers has a substantial association to standard operating procedure in improved service delivery. Moreover, most of the healthcare workers have attained a diploma as professional in different cadres. This shows the healthcare workers have the requisite education to comply to the standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records. Compliance to standard operating procedure was found to be associated with level of education. The study affirms the need to strengthen medical records documentation through improved capacity building (skill transfer) of the staff and with strong quality controls (Demirci, Acamur, & Bulut., 2017). Regarding age and gender findings show that they were not significantly associated with the compliance to SOP for documentation by healthcare workers. This implies that age and gender are constant variables that cannot change or manipulate the compliance of documentation of medical records. This was in agreement with the study done by Hamm et al., (2019) that the quality of data does not differ with gender roles assigned. However, Ahwidy & Pemberton, (2016) was in disagreement that in accumulation, the work of an experienced population in terms of age and gender influenced precise products. Subsequently, there was a significant association between cadre, work experience, and the level of education of respondents to the extent of compliance to SOP for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers respectively at Bungoma level 4 hospital. In regards to cadre, this was consistent with the study done by Cherry et al., (2011) that operational improvements were achieved through increased documentation accuracy and implementation of evidence-based practices per cadre. And it was also consistent with the study done by Demirci et al., (2017) revealed that nurses do not record their actions to a great extent and they only record observations, this focused particularly on the nursing cadre attitude on documentation. Although cadre had a stronger association compared to the education and the work experience. Similarly, with work experience and the level of education, this was in tandem with (Tims, 2013) that education and work experience of health workers has a substantial association with the standard operating procedure in improved service delivery. It implies that work experience and level of education influence the compliance to the standard operating procedure in medical records documentation, whereby the inadequate use of information systems by healthcare workers affects their performance on the use of electronic medical records. Besides, it was also in contrast with Maina et al., (2014) which identified completeness, timeliness, accuracy, and reliability of the data to be the main causes of poor data quality in the documentation of medical records. As of education level, Walsh and Dougherty (2012) argued that there is a need to make clear policies to avoid wrong administration of medication. It can be achieved by conducting regular training of staff on documentation.

5. Limitation

- Limitations of the current study pertain to participants' reporting bias, that is, the respondents were reluctant to report on their shortcomings regarding poor documentation and compliance to SOP’s. Their honesty and willingness to share their knowledge for this study. Moreover, the findings of the current study may lack external validity beyond Bungoma level 4 hospital, and thus, cannot be generalized to all level 4 facilities in Kenya.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The current analysis has confirmed the compliance level was very low at 47.2%. Cadres, level of education, and work experience of healthcare workers had a significant influence on the compliance to the standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records by the healthcare workers at least for the case of Bungoma Level 4 hospital. Regarding age and gender, there was no statistical significant association with the compliance to SOP for documentation of medical records by healthcare workers. The immediate implication is that the county health management team needs to foster continuous in-service training and refresher courses to strengthen the healthcare worker’s skills in compliance with the standard operating procedure for documentation of medical records. Future research should otherwise consider looking at the influence of institutional characteristics on healthcare worker’s compliance to standard operating procedures for documentation of medical records in Bungoma level 4 hospital and beyond. Moreover, more randomly selected facilities could also be included in future studies to increase the external validity of the findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to thank the Bungoma Level 4 Hospital Health Management Team and the County Health Management Team for their support, the Kenyatta University, Health Management and Informatics Department.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML