-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2020; 10(2): 58-63

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20201002.03

Budgeting at the County Level in Kenya: What has Worked, Challenges and Recommendations

Njuguna K. David1, Elizabeth Wangia2, Stephen Wainaina3, Theresa Watwii Ndavi4

1Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

2Monitoring & Evaluation Specialist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

3Independent Consultant, Nairobi, Kenya

4Economist/Independent Researcher, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Njuguna K. David, Health Economist, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The objective of this paper is to assess policy implementation from the perspective of budget allocations and actual expenditures in the context of the health care sector in a poor country. The study is limited to the case of the health care system of Kenya, more specifically whether there was a change in the Kenyan government’s allocation and spending of health care resources in relation to their set priorities in distribution of funds.

Keywords: Budgeting, County, National, Health, Expenditure, Challenges and Policy

Cite this paper: Njuguna K. David, Elizabeth Wangia, Stephen Wainaina, Theresa Watwii Ndavi, Budgeting at the County Level in Kenya: What has Worked, Challenges and Recommendations, Public Health Research, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 58-63. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20201002.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

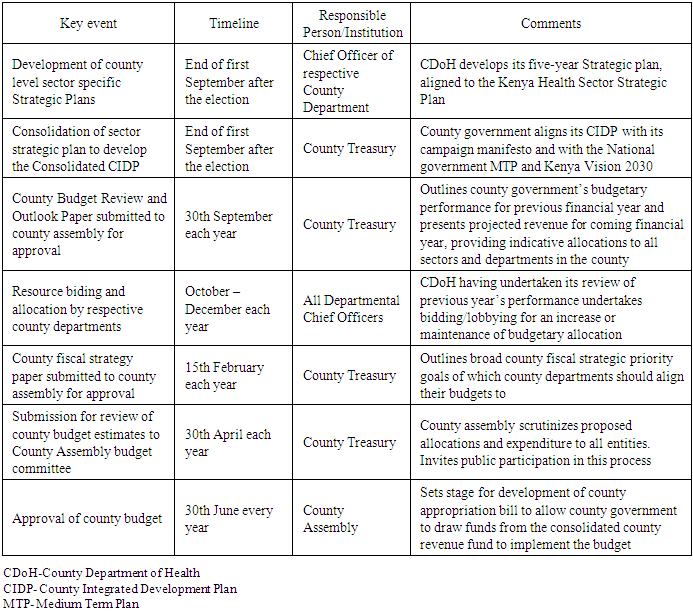

- A government budget is a financial plan that outlines the expected government revenue and the estimated government expenditure over time, usually one year. It outlines government policies, strategies and fiscal implications of public programs over the financial year while identifying essential resources for program implementation [1]. It can be forward-looking (planning) or backward-looking, thus it can either forecast on future activities or analyze past events such as performance evaluation [2]. In Kenya, each county is required by the county government act to develop a plan to facilitate development, which forms the basis for all budgeting and spending [3]. The county national treasuries communicate the indicative budget ceilings to the various sectors through the approved County Budget Review and Outlook Paper which gives an indication of how much the health sector will receive. Advocacy for more health funding should, therefore, be done before its release. Sector working groups guide their respective ministries or departments in preparing three-year rolling budget allocations to proposed programs and activities and produce reports which inform the County Executive Committee in refining the sector ceilings [4].At the county level, budgeting begins with the integrated development planning process which involves planning and establishment of financial and economic priorities for the county over the medium term. All stakeholders involved in budget preparation issue guidelines then make estimates of the county government’s revenues and expenditures. The County Fiscal Strategy Paper is adopted and submitted to the County Assembly to scrutinize the votes in the estimates before approval by the County Executive Committee for Finance. It includes the budget estimates and the appropriations bill. Once approved, the county assembly enacts an appropriation law and other laws required for budget implementation after which implementation begins [5]. The Governor assents to the Appropriation Bill then it is published in a gazette. The Governor then signs the general warrant, a legal authority to the Executive Committee Member for Finance, County Treasury to authorize expenditure based on approved estimates. The county executive committee member for finance issues departmental warrants to authorize budget entities to spend their budgets as provided for in the appropriation law. The county treasury must maintain a file of all the asserted and published appropriation laws alongside the approved estimates.The Health sector Annual Operational Plans (AOPs) process and budgeting process is similar and begins at the AOP review summit where the sector identifies the priorities for the coming year. This summit normally coincides with the treasury releasing the Budget Outlook Paper that elaborates the respective sector budgetary ceilings. The priorities identified from the AOP review summit are used to bid for resources at the hearings in the Sector Working Group. The AOP planning tools, guidelines and resource envelopes for planning units are then prepared based on the indicative government resources allocated from the Sector Working Group hearings and declared resources from donor partners. The MoH then submits the consolidated ministry AOP through the Sector Working Group for funding consideration by Treasury. Treasury finalizes the national and county budget process and communicates back to ministries the resources they have been allocated. The MoH then revises its AOP based on resources confirmed by Treasury [6].The county health sector budgeting provides a framework for the county governments to effectively and efficiently deliver on its health service delivery mandates. It also translates the medium-term County health sector objectives into annual actionable plans in a logical and sequential manner. Through a rational review of the County annual achievements, clear priorities are set for the County to focus on in the coming financial year operations, guided by its provided resource envelope, and the recommendations from the previous year. County health budgets also provide guidance to the County on key health sector priorities to focus on in the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) discussions for the next financial year for inclusion in the County Fiscal Strategy Paper that outlines Overall County’s priorities and financial allocations.County health sector budgets are crucial for achieving fiscal discipline, allocative efficiency, technical efficiency, and stabilization of the economy. Fiscal discipline is achieved by keeping budgetary expenditure consistent with medium term priorities, maintaining a strong fiscal revenue and supporting revenue generation within the context of sustainable public finances. The budget provides a precise reflection of the county’s expenditure priorities and enables citizens to challenge it based on the stated policies and public pronouncements. Allocative efficiency is the capacity of the county to distribute resources based on the effectiveness of public programs in meeting its strategic objectives. The budget shifts resources from less productive to more productive areas in correspondence to the county’s objectives. It requires proper arrangements within line ministries for sector policy formulation and sufficient technical capacity within spending agencies to select the most cost-effective programs, projects, and activities.Technical efficiency refers to the ratio of resources consumed by the county’s agencies to the output produced or purchased. It is achieved when maximum outcomes are achieved for a given level of inputs and no other combination of inputs can achieve a higher outcome. It is dependent on arrangements to implement programs within spending units based on efficient and effective management systems. The stabilization function of the budget helps the county to achieve and maintain the desired level of performance of the economy. It is done by ensuring both taxes and expenditures are sustainable in the long run [7]. Historically, line-item budgets were the predominant method of presenting government budgets. Line-item budgeting was criticized for holding public agencies accountable for only what was spent and not what had been achieved from the expenditure [8]. Besides, the Ministry of Planning and National Development had a weak link to the Ministry of Finance and used circulars to guide the government planning processes. This created a mismatch between planning and budgeting cycles. In 2012, the Government of Kenya enacted the Public Finance Management Act (PFM Act) 2012 which entrenched the use of Program Based Budgeting as the main tool for government sector planning and budgeting, thus harmonizing the two activities. Program-Based Budgets are organized around programs and sub-programs with funds allocation linked to technical priorities and outcomes. It can link sector level technical priorities with budgeting; and enhance transparency, openness, and efficient use of public resources through public participation [9].Several laws regulate county planning and budgeting in Kenya. First, Chapter 11 of the Constitution of Kenya 2010, requires county governments budgets to have estimates of revenue and expenditure, differentiate between recurrent and development expenditure, give proposals for financing any anticipated deficit for the period to which they apply, give proposals regarding borrowing and other forms of public liability that will increase public debt during the following year [10].Second, the County Government Act, 2012 requires county governments to develop plans including: Five year County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP), ten year programme based county sectoral plan as parts of the CIDP, county spatial plans and cities and urban areas plans. The county planning facilitates the development of a well-balanced system of settlements and ensure productive use of resources (Section 103 (b)). It also ensures meaningful engagement of citizens in the planning process (Section 105 (d)) and mandatory public participation in the county planning process (Section 115) [3].Third, the Public Finance Management Act, 2012 calls for an integrated development planning for long-term and medium-term planning as well as financial and economic priorities for the county over the medium-term. It also requires the integrated development plan to include strategic priorities for the medium-term that reflect the county government’s priorities and plans, a description of how the county government is responding to changes in the financial and economic environment; and programs to be delivered (section 126) [11]. Fourth, the Urban Areas and Cities Act, 2012 emphasizes the need for five year integrated development planning by county governments and the need to align county annual budgeting to the plan. An integrated urban or city development plan shall bind, guide, and inform all planning for development and decision-making and ensure comprehensive inclusion of functions (Section 36 (2)) [12].Fifth, Intergovernmental Relations Act 2012 grants for the establishment of a framework for consultation and cooperation between national and county governments, and among county governments. It establishes the National and County Government Coordinating Summit which is the apex body for intergovernmental relations [13].County expenditure should not exceed the county government's total revenue and at least thirty percent of a county budget should go towards development expenditure over mid-term. Borrowings should only be used to finance development expenditure and maintained at a sustainable level approved by the county assembly. The county treasury should ensure that fiscal risks are managed prudently and the expenditure on wages and benefits to public officers does not exceed a percentage of the total county revenue as set by the CEC [5]. The county health budgeting process should happen before or within the dates indicated in Table 1.

|

2. Methods

- This study was conducted in 2019. We adopted a mixed methods approach for this study. The quantitative component of the analysis was based on data drawn from Government of Kenya budget documents, the Integrated Financial Management Information System. We also implemented semi-structured interviews with 15 counties in the health sector. Vihiga, Busia, Trans-Nzoia, Migori, Kisii, Nandi, Kakamega, Bomet, Kisumu, Nakuru, Turkana, Homabay, Baringo, Nyamira and Siaya Counties.

3. Results

- Overall the budgeting process as prescribed in the PFMA (2012) is adhered to by both the national and county governments. The process commences on August 31st of each year where a budget circular is released by the National Treasury and provides clear guidelines on how to develop the budget for the upcoming MTEF cycle/budget. It has been noted that the CDoH have officers who are capacitated on preparing a budget in accordance with the PFMA (2012). Stakeholders from both within and without the sector and are involved in the budgeting process as their inputs are pertinent. There is the provision for changes to be made to the budget through the supplementary budget, so counties are able to reprioritize in line with funding realities. Throughout the process there are budget oversight agencies including the internal and external auditor, controller of budget as well as the County Assembly that are tasked with overseeing how the allocated funds are spent within the sector. A standardized budget tool developed by the Ministry of Health (MoH) has made it easier and more efficient to prepare the budget. With the positive strides made in advancing technology, procurement, monitoring and evaluation are digitized making transparency and accountability easier. The budgeting process is a timely process that follows the financial calendar of July-June each year. Each department is allowed ample time to develop their budget as per the budgeting cycle. It has been noted that the CDoH within the counties actively take part in the budget-making process. Every county uploads their budgets on the county website in a timely manner for both transparency and accountability.

4. Challenges

- There are however some challenges experienced at the county level that hamper the budgeting process from progressing efficiently. PBB is not linked to the IFMIS system and with line budgets typically uploaded into IFMIS, this makes it difficult to track activities within the PBB. Service delivery within health is provided by the public sector, private sector and development partners. With all these stakeholders at the provider level, the sector is not able to determine the full resource envelope for health as partners tend to not disclose their contributions to the resource envelope. There is also political interference on already agreed on budgets leading which sometimes leads to poor execution of budgets resulting in incomplete projects and accumulation of pending bills. Poor monitoring and evaluation of projects may also lead to not only incomplete projects but also poor workmanship on said projects. There are also misplaced priorities which results in no value for money.Health provision relies on the proper coordination between national and county governments however it has been noted that there is poor coordination between the two on projects such as CDF and county health facilities. It has also been observed that there is poor inter-sectoral coordination among key departments including BQs that are generalized rather than itemized. Fiscal indiscipline is experienced within the health sector as there is spending for items that were not included in the budget.Furthermore the lack of stakeholder involvement during instances such as determining departmental ceilings and supplementary budget making is hindrance in proper budgeting within the health department. The lack of stakeholder involvement is sometimes accompanied by unstructured or even lack of public participation during the budgeting making which is an opposite step. The non-involvement is sometimes due to inadequate sensitization and information sharing of the budgeting cycle to the stakeholders. Within the department there are officers who are not aware of the intricacies of the budgeting cycle and are thus unaware of their needed involvement. Departments also face inadequate dissemination of all the pertinent budget making documents such as the guidelines, manuals and legal framework.During implementation, departments experience late disbursement of equitable share funds from the exchequer and convoluted procurement processes, leading to poor executing of budgets. The country treasury on some occasions authorize un-prioritized payment within IFMIS. Additionally, departments are faced with pending claims not being paid by the 30th June.Health departments usually experience challenges in meeting PFMA (2012) thresholds of 30 percent for development and 35 percent for the wage bill. The departments also face resource envelope constraints including lower collections of local revenue that was targeted and over-ambitious revenue projections. The departments are faced with challenges as figures are balanced by county treasury especially when thresholds have increased. Moreover, there is a disconnect between the PBB and the implementation of the CFSP.CDoHs are faced with inadequate technical capacity in terms of number of staff dedicated for budgeting. Departments do not have an economist or health budget officer who would be tasked with all issues pertaining to funding for health. This is due to poor planning of HRH resulting in over recruitment of certain cadres/positions. During the budgeting process, donor funds including from Danida, World Bank and Linda Mama are included thereby increasing the ceiling, to the detriment of the department. Moreover, some of the donor funds allocated for instance from the World Bank and UNICEF come with conditions that require the public sector to increase their budget for health. There is an inadequacy of legislation and policies to support counties in ring-fencing funding for health for instance a County Facility Improvement Fund (FIF) bill that would allow counties to retain the rrevenues generated by health facilities for use in improving health infrastructure and other essential services towards UHC. Moreover not all revenue streams are captured in the PBB. The counties not only face hostility during revenue collection more so through public apathy but there is intercounty conflict witnessed during revenue collections.

5. Challenges with IFMIS

- The IFMIS system is an automated system that is used for public financial management. It interlinks planning, budgeting, expenditure management and control, accounting, audit and reporting and is designed to improve systems for financial data recording, tracking and information management for improved transparency and accountability.That being said, counties experience various challenges with the system. One challenge is fiscal indiscipline due to expenditure beyond the vote items being paid through a ‘default’ payment system. The closure of the auto-creation module that allows for paying pending bill, is done arbitrarily leading to the accumulation of pending bills. Challenges are also experienced when uploading and/or approving procurement plans. Technological issues including total collapse of the IFMIS system, unpredictable network challenges, frequent software upgrades of the system and uncontrollable server speeds, pose time constraint and access challenges. Moreover the system neither gives alerts nor stops execution of processes when there is an error with entries. Being an open source system, IFMIS is exposed to cyber security crimes. There is also the lack of synchronization and interconnection of IFMIS with iTax portal and internet banking including with CBK respectively. There are challenges experiences when attempting to reset the password. There is not only inadequate technical capacity on IFMIS but also continuous capacity development for IFMIS operators is lacking. There is also lack of sensitization for suppliers on the supplier definition in the IFMIS system.Delays are experienced in the updating of the IFMIS general ledger while some of the IFMIS modules are not fully operationalised for instance bank reconciliation and cash management.

6. Mitigation

- Overall all CDoH must adhere to PFMA 2012 and related regulations. It is recommended that the financial systems be re-engineered to reduce the bureaucratic procedures at both the County and National level. IFMIS system should be reviewed and re-designed so as to enable the capturing of information from PBB. Sensitization of other senior officers on the operations of IFMIS needs to also take place. Counties are also recommended to strengthen their M&E activities and accountability mechanisms for instance by CoB, the County Assembly and CSOs through advocacy. The role of the CoG should be enhanced to support the accountability mechanisms for the counties.All stakeholders should actively participate in the budget making process. To ensure this, advocacy to key stakeholders involved in the budgeting process, both internal and external, on the budget making cycle needs to be strengthened. The County governments should also ensure proper public participation during the budget making process including providing civic education and enforcing public participation regulations and guidelines. Ensure there is planned dissemination and sensitization of the budgetary documents and the legal frameworks. Processes of the supplementary budget making should be customized to ensure all the stakeholders are involved. It is also recommended that departments be made autonomous fiscal entities that would allow them for instance to access funds directly from special purpose accounts. There needs to be ring fencing of payments requisitioned to the national treasury at the point of actual payments. This is need for the procurement processes to be streamlined to reduce unnecessary details and hurdles. Counties need to continue lobbying particularly through the senate, for timely disbursements. The departments should also practice better financial discipline so as to prevent financial recurrent pending bills. This can be done by implementing a debt management policy that includes reviewing sector expenditure reports and submitting them on time to reduce all pending bills and allow for requests to be made and inherently disbursement of funds in good time. They should also implement their targeted advocacy initiatives including towards influential members like the senior leadership. These advocacy initiatives to the political wing aid in maintaining planned priorities. The CDoH should initiate a programme technical review of the budget making process as the process commences each year. Sector working groups should also be operationalized within the CDoH. Moreover interdepartmental consultation needs to be enhanced as initiated by the CDoH. It is also highly recommended that the CDoH have a dedicated budget officer who would be tasked with ensuring all planning and budgeting processes throughout the budget cycle are executed efficiently including initiating pro-active planning for enhancing outputs and reducing inter-departmental conflicts.Counties should seek out innovative ways to expand their revenue base – PPP including mapping all revenue sources, banking in the CRF and strengthen controls including promoting automation. Counties must ensure the there is a partners coordinating framework that provides for full disclosure of the health partners resource envelopes. Moreover, Counties should also sign and enforce MOUs with health partners that obliges them to fully disclose their financial/resource contributions. That being said, when the CDoH reviews its allocation it should omit grants and loans to be able to clearly determine their allocations from the public sector.

7. Conclusions

- Budgeting provides counties with an economic map of their operations. While positive strides have been made in the county health budgeting process, there is need to enhance coordination between national and county health departments, political independence, stakeholder involvement, funding process and spending against limited revenue to best meet the needs of the population. Reviewing and re-designing IFMIS system to capture information from PBB are the essential next steps for improving budgeting at the county level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The We are grateful to the budgeting teams from Vihiga, Busia, Trans-Nzoia, Migori, Kisii, Nandi, Kakamega, Bomet, Kisumu, Nakuru, Turkana, Homabay, Baringo, Nyamira and Siaya Counties.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML