| [1] | Williams OS, Hamid RA, Misnai MS. Accident Causal Factors on the Building Construction Sites: a review. IJBES 2018; 5(1): 78-92. |

| [2] | Lingard H. Occupational health and safety in the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics 2013; 31 (6): 505-514. |

| [3] | Van Heerden JHF, Musonda I, Okoro C. Health and Safety Implementation Motivators in the South African Construction Industry. Cogent Engineering March 2018; 5: 1446253. |

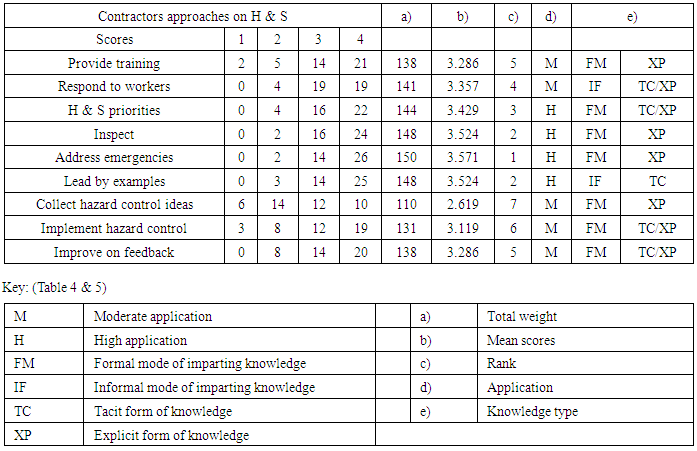

| [4] | Phoya S, Eliufoo H. Perception and Uses of Stakeholders’ Power on Health and Safety Risk Management in Construction Projects in Tanzania. JCEA 2016; 10:955-963. |

| [5] | Okori CS, Musonda I, Agumba JN. A factorial analysis of safety performance measures: a study among construction workers in Gauteng, South Africa. “Emerging trends in construction organisational practices and project management knowledge area”. 9th CIDB Postgraduate Conference February 2-4, 2016, Cape Town, South Africa. |

| [6] | Pandit B, Albert A, Patil Y, Al-Bayati AJ. Fostering Safety Communication among Construction workers: Role of Safety Climate and Crew- level Cohesion. Int.J.Environ.Res.Public Health 2019; 16(1): 71. |

| [7] | Alomari, K, Gambatese, J, Anderson J. Opportunities for Using Building Information Modeling to Improve Worker Safety Performance. Safety 2017; 3(1); 7. |

| [8] | Vitharana VHP, De Silva GHMJS, De Silva S. Health hazards risk and safety practices in construction sites – A review study. The Institution of Engineers Sri Lanka 2015; xviii (03):35-44. |

| [9] | Kines P, Andersen LPS, Spangenberg S, Mikkelsen, KL, Dyreborg J, Zohar D. Improving construction site safety through leader-based verbal safety communication. J Safety Res. 2010; 41(5):399-406. |

| [10] | Musonda, I, Pretorius JHC. Effectiveness of economic incentives on clients’ participation in health and safety programs. Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering June 2015; 2(57):2–7. |

| [11] | Cecchini M, Bedini R, Mosetti D, Marino S, Stasi S. Safety Knowledge and Changing Behavior in Agriculture Workers: an Assessment Model Applied in Central Italy, SH@W 2018; 9: 164-171. |

| [12] | Okoye PU, Ezeokonkwo JU, Ezeokoli FO. Building Construction Workers’ Health and Safety Knowledge and Compliance on Site. Journal of Safety Engineering 2016; 5 ;( 1):17-26. |

| [13] | Mrema EJ, Ngowi AV, Mamuya SHD. Status of Occupational Health and Safety and Related Challenges in Expanding Economy of Tanzania. Analysis of Global Health 2015; 81(4); 538-547. |

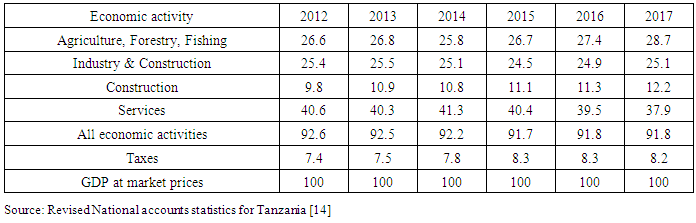

| [14] | National Accounts of Tanzania mainland (2015), Dar es Salaam; Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics 2019 [cited 18th February 2019]; available from: https://www.nbs.go.tz/. |

| [15] | Wells J. Informality in the construction sector in developing countries. Construction Management & Economics 2007; 25: 87-93. |

| [16] | Ofori G. Construction in Developing Countries, Construction Management and Economics, 2007; 25(1):1-6. |

| [17] | Ofori G. Challenges facing construction industries in southern Africa. The Construction Business Journal 2001; 4; 6: 24-27. |

| [18] | Liyanage C, Ballal T, Elhag T. Assessing the process of Knowledge Transfer-An empirical study. Information and Knowledge Management 2009; 8(3): 251-265. |

| [19] | Nonaka I, Takeuchi H. The knowledge creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York; Oxford University Press 1995. |

| [20] | Eliufoo HK. Knowledge creation and transfer in construction organisations in Tanzania. Doctoral thesis in Building and Real Estate Economics, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH). Stockholm Sweden 2005. |

| [21] | Davenport TH, Prusak L. Working knowledge: How organisations manage what they know; Boston, Massachusetts; Harvard Business School Press; 1998. |

| [22] | Bhatt GD. Knowledge management in organizations: examining the interaction between technologies, techniques and people. Journal of Knowledge Management 2001; 5(1): 68-75. |

| [23] | Niss C. Knowledge brokering across the boundaries of organisations: an interactionist interpretation of a temporary “mirror-organisation”. A licentiate thesis, Department of Industrial Economics and Management 2002; Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. |

| [24] | Sverlinger PO. Managing knowledge in professional service organisations. A doctorate thesis, Department of Service Management 2000; Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden. |

| [25] | Roberts J. “From know-how to show-how? Questioning the role of information and communication technologies in knowledge transfer,” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 2000; 12(4):429-443. |

| [26] | Phoya S. Health and Safety Risk Management in Building Construction Sites in Tanzania: The Practice of Risk Assessment, Communication and Control. Department of Architecture Chalmers University of Technology; 2012; Thesis for the Degree of Licentiate of Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden. |

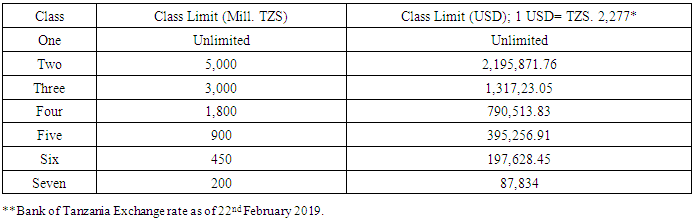

| [27] | Tanzania Contractors Registration Board (TCRB) publication; Classification of contractors [cited 25th February 2019] available at: http://www.crb.go.tz. |

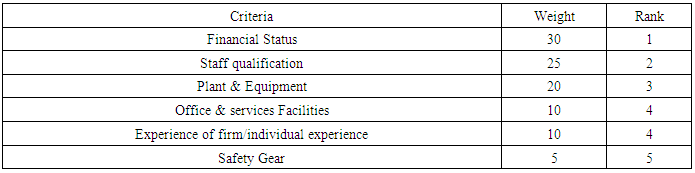

| [28] | Tanzania Contractors Registration Board (TCRB) publication. Registration criteria booklet; [cited 25th February 2019] available at: http://www.crb.go.tz. |

| [29] | Mugenda OM, Mugenda, AG. Research methods: Quantitative and qualitative Approaches. (2003). Nairobi: African Centre for Technology Studies. |

| [30] | Suri H. Purposeful Sampling in Qualitative Research Synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal 2011; 11(2):63-75. |

| [31] | Patton MQ. How to use qualitative methods in evaluation. California: SAGE Publications; 1987. |

| [32] | Zin SM, Ismail F. Employers’ Behavioural Safety Compliance Factors toward Occupational, Safety and Health Improvement in the Construction Industry; Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences Elsevier 2012; 36:742 – 751. |

| [33] | Opeyemi SM, Hamid RA, Misnan MS. Accident causal factors on the Building Construction Sites: a Review 2018; IJBES 5(1):78-92. |

| [34] | Agumba J, Pretorius HM, Haupt T. Health and safety management practices in small and medium enterprises in the South African construction industry. Acta Structilia 2013; 20. |

| [35] | McGeorge D, Palmer A. Construction Management: New Directions. 2nd Revised edition. Blackwell Publishers; 2002. |

| [36] | Burgess TF Modelling quality- cost dynamics. IJQRM 1996; 13(3): 8-26. |

| [37] | Kim Y, Park J, Park M. Creating a culture of prevention in occupational safety and Health practice, SH@W 2016; 7: 89-96. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML