-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2019; 9(2): 30-38

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20190902.02

Prevalence of Hypertension among Adult Residents of Selected Communities in Tano North District in Ahafo Region, Ghana

Kingsley Boakye 1, Comfort Arthur 2, Augustine Amissah 2

1Department of Public Health, Kumasi Metropolitan Health Directorate, Kumasi, Ghana

2Department of Health Promotion, Cape Coast Teaching Hospital, Cape Coast, Ghana

Correspondence to: Kingsley Boakye , Department of Public Health, Kumasi Metropolitan Health Directorate, Kumasi, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Hypertension is one of the major diseases in recent years contributing significantly to the mortality rate in Ahafo Region and Ghana at large. The study was conducted to determine the prevalence rate of Hypertension in the Tano North District of the Ahafo Region in Ghana. A community based cross sectional study was used to collect quantitative data from 242 adult residents of Tano North District. Purposive and simple random sampling techniques were employed. Data was collected through structured questionnaire and a compilation form for the anthropometric measurement. Data was entered using Microsoft Excel version 2016 for validation before imported into STATA software version 14.0 for statistical analysis. Multivariate regression and chi-square analysis were also performed using confidence level of 95% and 5% margin error. Prevalence of hypertension was found to be 90 (37%) respondents. Commonly used oil (palm oil) was found to be significantly associated with hypertension (X2=9.2382, P=0.002). Hypertension was mostly prevalent among the aged (50 years and above). Age was therefore found to have a significant association with hypertension (X2 =12.63, P=0.013). Smoking was associated with hypertension (X2=8.431, P=0.0473). A group of variables like BMI, stress days, fruit days, vegetable days and glucose level of respondents (independent variables) were found to reliably predict hypertension since the overall Prob > F = 0.0151 was smaller than 0.05. The authors recommend to the district health facilities to embark on monthly outreach screening to help determine hypertension among unknown hypertensive residents in Tano North District.

Keywords: Adult Residents, Blood Pressure, Cardiovascular Disease, Hypertension, Prevalence

Cite this paper: Kingsley Boakye , Comfort Arthur , Augustine Amissah , Prevalence of Hypertension among Adult Residents of Selected Communities in Tano North District in Ahafo Region, Ghana, Public Health Research, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 30-38. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20190902.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure more than 140mmHg or equal and with a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mmHg which leads to cardiovascular syndrome emanating from multidimensional factors [1]. Hypertension is constant pumping of blood with excessive force through the blood vessel [2]. Hypertension is classified as primary and secondary with the primary representing 90-95% of the entire cases and is categorized as high blood pressure with no clear cause but with some determinants [3]. Secondary hypertension is caused by identifiable factors including environmental factors, genetic and lifestyle risk determinants [4]. There are other determinants of hypertension including stress, obesity and lifestyle behaviour in urban communities [5]. Hypretension is a disease of public health burden around the globe due to problems that are associated with the management and control of blood pressure and the low awareness level and treatment of hypertension [6]. The disease is mostly found in adults especially the aged population and is noted as the major predictor of cardiovascular diseases [7]. The problem is that hypertension kills people slowly because it is often not accompanied with warning signs and due to that many people do not realize they have the disease [2]. Hypertension can cause serious damage to health of people by reducing the inflow of blood and oxygen to the heart due to hardening arteries. This in-turn causes heart attack, heart failure, stroke and chest pain. The symptoms of hypertension emanate from damages of end-organ and presentation depending on organs that are affected [8].Hypertension continues to be a disease burden to Public Health around the globe. The year 2000 saw more than 1/4th of the adult population in the world as hypertensive patients. It is also predicted 1.5 billion cases in 2025 [9]. Notwithstanding that, the global prevalence of blood pressure among adults in 2014 was 22%, with a national prevalence of 20% among Indian adults [10]. Hypertension according to WHO accounted for 7.5 million deaths with reported cases of 57 million DALYs globally. It is noted to be a predictor of cardiovascular mortality and accounts for 20-50% of all mortalities [11].Hypertension is found to be increasing rapidly in Sub-Saharan Africa due to increasing age with a continuous effect of determinants of hypertension including unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and obesity [12]. It is also estimated that cardiovascular diseases associated deaths will be up to 23 million with 85% of the deaths occurring in middle - income countries by 2030 [13]. The situation is worst in Ghana as adult hypertension is found to be high in rural and urban communities with a percentage ranging from 19% to 48% [14]. New cases of hypertension in public health facilities in Ghana saw an increase from forty-nine thousand and eighty-seven (49,087) cases reported in 1988 to five hundred and five thousand, one hundred eighty (505,180) in 2007 [15]. The early detection, treatment and control of hypertension are generally low in Ghana [5]. The low detection rate of hypertension is very dangerous which indicates that many people are harbouring the disease without being aware of their status and is associated with sudden death. Most patients have hypertension without knowledge and due to that, they do not report to the hospital for early diagnosis and even if they are diagnosed, they do not take adequate treatment to control their high blood pressure [5]. This is because most of the patients do not experience the symptoms. However, early detection could help the management and prevention of hypertension. Tano North District in recent years reported high incidence of hypertension among adults. Thus hypertension in Tano North District accounted for 1.3% (451) of the total hypertension reported by Ahafo Regional Health Directorate (34,708).This finding suggests a higher prevalence rate of hypertension in Tano North District in the Ahafo Region and factors accounting to the high hypertension rate includes smoking, drinking of alcohol, stress, poor dietary practice, other lifestyle and environmental factors. Interventions implemented to ensure optimum health with regard to hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases in the district have been in total fiasco. Mortalities associated with coronary heart diseases and stroke doubles for every 20mmHg rise in systolic blood pressure with an increase in diastolic blood pressure by 10 mmHg [16]. Considering the mortalities associated with hypertension it is therefore necessary to ascertain the hypertension situation in the District. Therefore, this research will help provide relevant data on the prevalence rate of hypertension, set the pace for strengthening health education in the Tano North District as well as devise appropriate and feasible strategies or intervention to combat hypertension in the district.

2. Materials and Methods

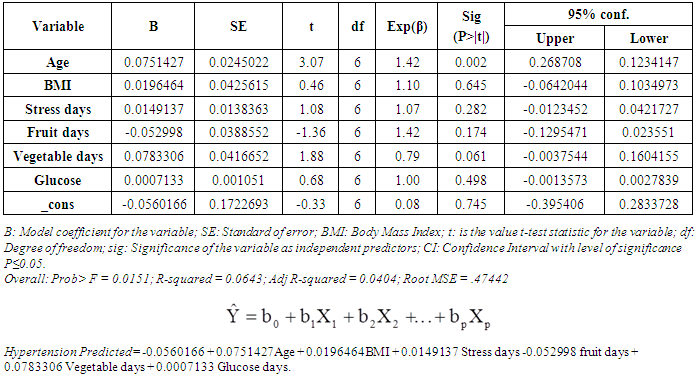

2.1. Study Area

| Figure 1. Map showing Tano North District |

2.2. Study Design

- A community based analytical cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the prevalence of hypertension among adult residents of Tano North District.Source PopulationAll adult residents of Tano North District were the source population. The study focused on adults from 18 years and above.Study PopulationAll adult residents from 18 years and above who were randomly selected were chosen as the study population.Inclusion CriteriaThe study only included adult residents from 18 years and above in the four selected communities in Tano North District (Campso, Koforidua, Susuanho and Duayaw Nkwanta) who were willing and ready to participate.Exclusion CriteriaAdult residents who were mentally unsound, deaf, mute, blind and could not read and comprehend the written and oral instructions in the questionnaire and answer them accordingly were excluded. Adult residents who decline to answer the questions were also excluded from the study.Sample Size DeterminationThe calculation for the sample size was based on the formula put forward by Cochran and Biswas (2013). The assumed hypertensive patients were 19%, confidence interval of 95%, margin error of 5% and additional 2% was added to cater for attrition and non-response. A sample size of 242 was thus derived which the researchers used as the sample size for the study.Sampling TechniquesA community durbar was organised for all the 4 communities (Duayaw Nkwanta, Koforidua, Susuanho and Campso) with about 430 participants. Adults that were present at the durbar grounds were selected using simple random sampling. ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ were written on pieces of papers and respondents were asked to pick from a container. Respondents that chose Yes were included in the study.Purposive sampling technique was used for the selection of the communities that were screened. They were purposively selected due to incidence of hypertension that was reported by the referral hospital of the district. Thus, majority of hypertension incidence reported by the district hospital were traced to these communities.Data Collection Procedure and AnalysisThe data collection tools used in collecting the research data were structured questionnaires and compilation forms.Questionnaires were administered to respondents for collection of relevant information for the study. The compilation form was used by data collectors to record anthropometric information such as weight, height, BMI, glucose level etc from the respondents. The quantitative data were coded and entered using Microsoft Excel 2016 version and then imported to STATA software version 14.0 for statistical analysis. Percentages in tables were computed for variables. Chi-square test, multiple regression and odd ratio analysis were computed as well.Data Quality ControlThree data collectors who were final year students in B.Sc. Public Health Education, Disease control officer and a nurse from Saint John of God hospital in Duayaw Nkwanta were recruited and trained to collect the data from the four communities. Training was given on how to fill both the questionnaire and the compilation form using observational checklist.Ethical ConsiderationBefore data collection, formal letter was sent to the District Health Directorate and the District Public Health unit to use their district as the case study to investigate into predictors of hypertension among adults in these communities of which permission was granted. At the communities, chiefs, elders and opinion leaders were verbally informed with prove of permission letter obtained from the District Health Directorate. The questionnaire was explained together with it’s risks and benefits to the respondents in the language they comprehend and they were informed that they can decline at any point if they so desire. Informed consent was also sought from respondents of the respective communities and they were assured of strict confidentiality of the information they will provide before data was collected.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

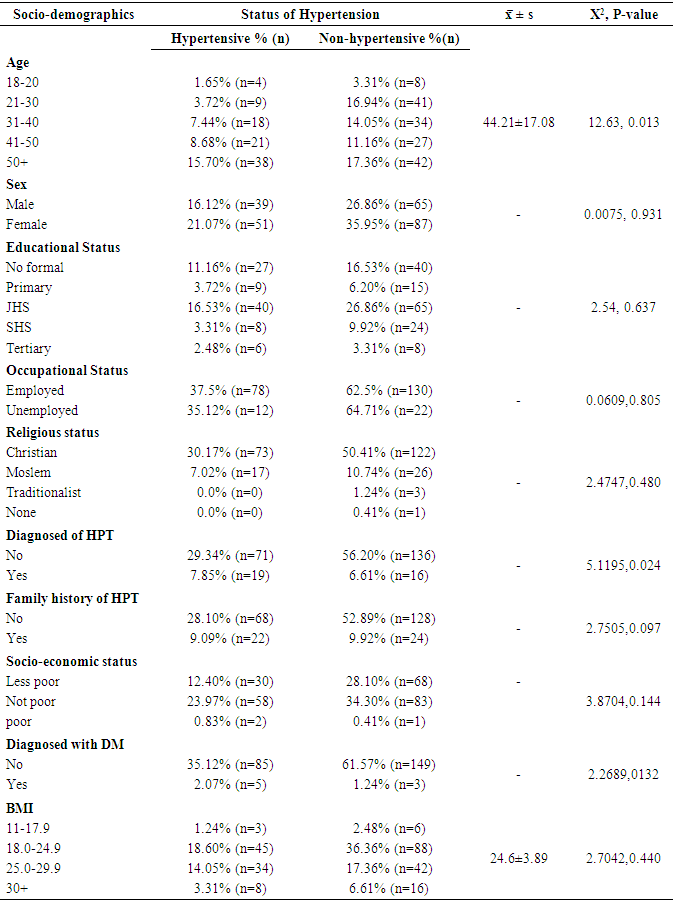

- Table two presents the socio-demographic characteristics of 242 respondents included in the study. Thirty-eight representing (15.71%) respondents aged 50 years above were hypertensive, followed 21 (8.68%) that were also within ages 41-50 respectively. The mean age of the respondents was 44 ± 17.08. Age had a significant association with hypertension (X2 =12.63, P=0.013) but there was no association between sex of respondents and hypertension (X2 = 0.0075, P=0.931). Fifty-one representing (21.07%) respondents with hypertensive status were females whiles their male counterparts scored 39 (16.1%). On education, 67 (27.69%) had no formal education. However, education was not associated with hypertension (X2 =2.54, P=0.637). Employed respondents scored the highest percentage (37.5%) among hypertensive respondents. Occupational status was however not associated with hypertension (X2=0.0609, P=0.805). Again, majority (30.17%) of respondents with hypertensive status were reported to be Christians, followed by Moslem (7.02%) respectively. Religion was however found not to be associated with hypertension (X2=2.4747, P=0.480). Out of the 37% patients that were found hypertensive, 19 (7.85%) respondents were with previous history of hypertension, whiles overwhelming 71 (29.34%) respondents formed new cases of hypertension. Being previously diagnosed of hypertension was highly associated with hypertension (X2=5.1195, P=0.024). Family history of hypertension did not have any significant association with hypertension (X2=2.7505, P=0.097) as overwhelming 28.1% of hypertensive respondents had no family history of hypertension. Out of the 90 respondents with hypertension, 2.07% had old history of Diabetes Mellitus (DM). Eighteen point six (18.60%) of the hypertensive respondents were with BMI ranging from 18-24.9 (normal weight), 14.05% with BMI of 25-29.9 (Overweight) and 3.31% with BMI of 30+ (obesity). Meanwhile, there was no association between BMI and hypertension (X2=2.7042, P=0.440).

|

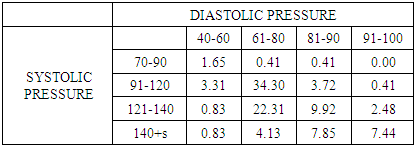

3.2. Prevalence of Hypertension based on Systolic and Diastolic Pressure

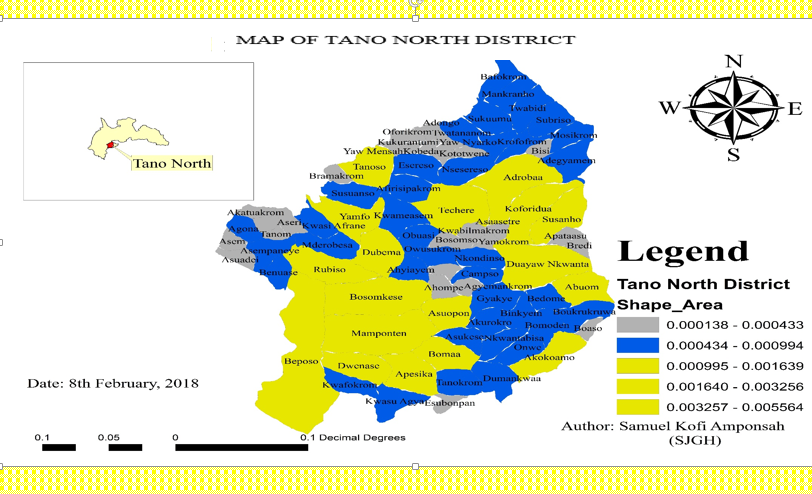

- 1.65% of the respondents were with low blood pressure, 61.61% were with ideal pressure, 29.34% were pre-high blood pressure and the remaining 7.4% were with high blood pressure. Figure 2 illustrates that 63% (n=152) of the respondents were non-hypertensive whiles 37% (n=90) were found to be hypertensive.

|

| Figure 2. Prevalence of Hypertension |

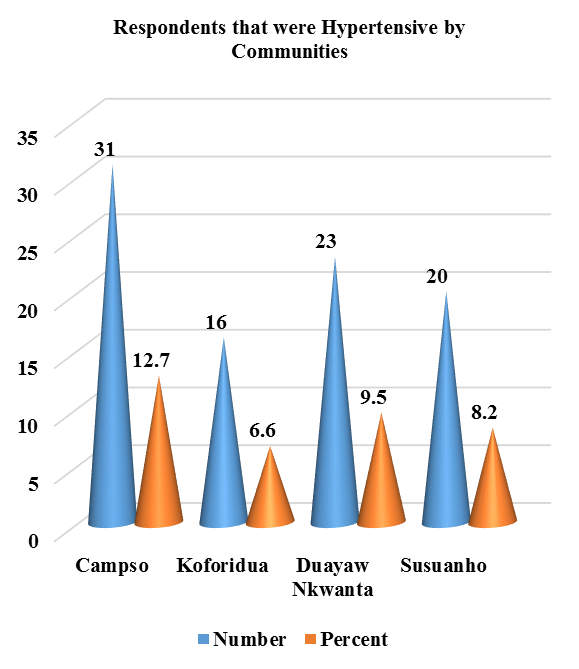

| Figure 3. Prevalence of Hypertension by Communities |

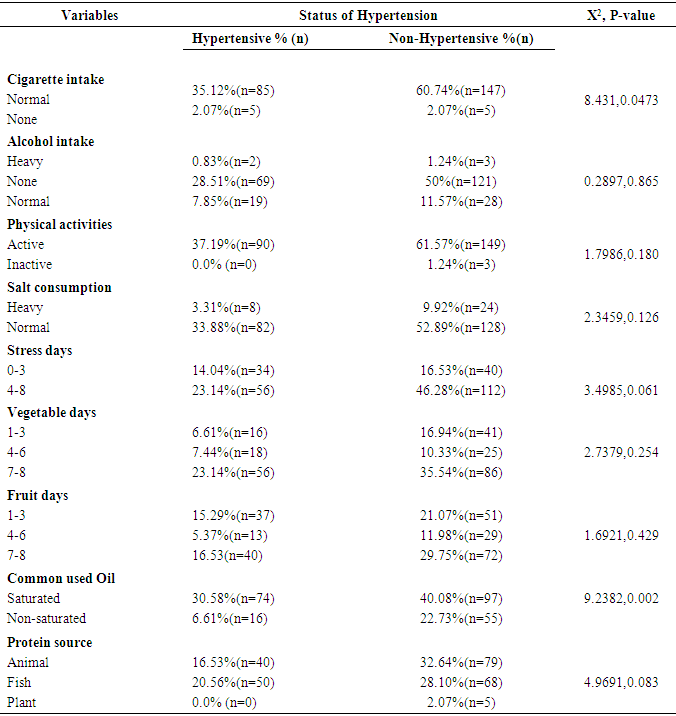

3.3. Relationship between Lifestyle and Hypertension

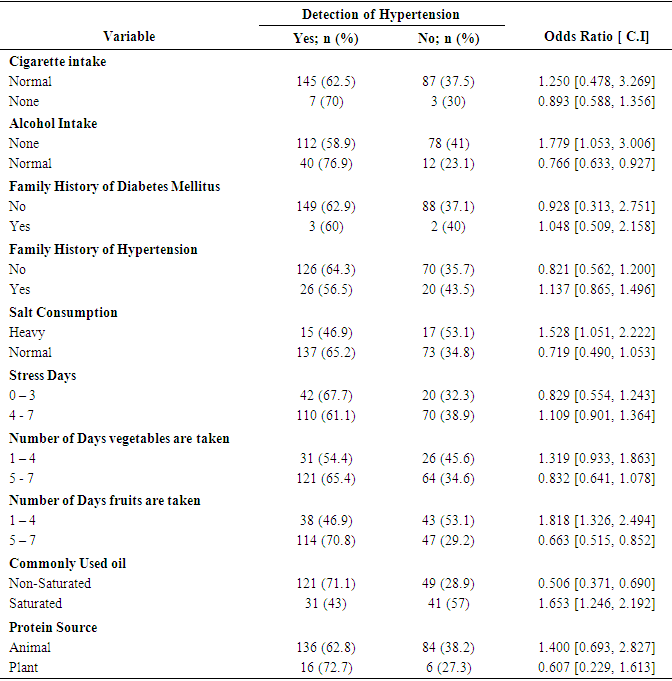

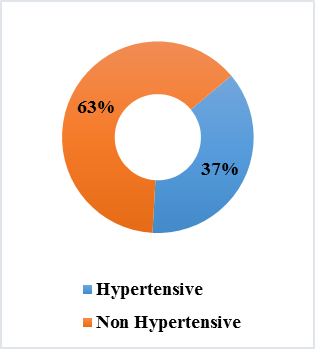

- Cigarette smoking showed significant association with hypertension (X2=8.431, P=0.0473). 35.12% of the respondents with hypertension were reported as smokers whiles 2.07% were found as non-smokers. Non-alcoholic intake respondents formed majority (28.51% and 50%) of both hypertensive and non-hypertensive respondents. Alcoholic intake therefore revealed no association with hypertension (X2=0.2897, P=0.865). Physical activities of respondents therefore had no association with hypertension (X2=1.7986, P=0.180). Salt consumption also had no significant association with hypertension (X2=2.3459, P=0.126). Meanwhile, salt consumption was heavy among 3.3% of respondents screened positive to hypertension. Stress days showed no association with hypertension (X2=3.4985, P=0.061). Stress days of 4-8 days formed majority of respondents among those screened positive to hypertension. There was no statistical association between vegetable intake days and hypertension (X2=2.7379, P=0.254). Fruit intake however showed no significant association with hypertension (X2=1.6921, P=0.429). Commonly used oil was reported significantly associated with hypertension (X2=9.2382, P=0.002), as 30.58% and 40.08% respondents with hypertension and without hypertension were commonly using saturated oil. Furthermore, there was no association between source of protein and hypertension (X2=4.9691, P=0.083).In order to control for confounding factors and determine the lifestyle practices that predispose one to the diagnosis of hypertension, odds ratio analysis was conducted.The results indicated that respondents who smoke Cigarrete and tobacco products were more likely to be diagnosed of hypertension (OR=1.250, CI:0.478 -3.269) than respondents who do not smoke (OR=0.893, CI:0.588 - 1.356). Respondents with family history of Diabetes were more likely to be diagnosed of the hypertension condition (OR=1.048, CI:0.509 - 2.158) as well as respondents with family history of hypertension (OR=1.137, CI:0.865 - 1.496). The result also revealed that respondents who consumed heavy or high quantity of salt were more likely to be diagnosed of hypertension (OR=1.528, CI:1.051 - 2.222). Respondents who were stressed out for more than four (4) days in a week were more likely to be diagnosed of hypertension, whiles those who eat vegetables between 1 – 4 days in a week were more likely to be diagnosed of hypertension (OR=1.319, CI:0.933 - 1.863). Respondents who take fruit between 1 – 4 days in a week were more likely to be diagnosed of hypertension (OR=1.818, CI:1.326, 2.494). The study also found out that respondents who commonly use saturated oil were more likely to be diagnosed of hypertension (OR=1.653, CI:1.246, 2.192) as well as respondents whose source of protein were from animals (OR=1.400, CI:0.693, 2.827).A group of variables Age, BMI, stress days, fruit days, vegetable days and glucose level of respondents (independent variables) can be used to reliably predict hypertension (dependent variables since the overall Prob> F = 0.0151 is smaller than 0.05. From the table, age can be said to have an association with hypertension and therefore can be used to predict hypertension when adjusted for glucose level (P=0.002).

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Addo, Smeeth & Leon [17] found 15.8% hypertension rate in Ghana but this study found 37% of the respondents to be hypertensive. One point sixty-five percent (1.65%) of the respondents were with low blood pressure, 61.61% were with ideal pressure, 29.34% were pre-high blood pressure and the remaining 7.4% were with high blood pressure. Out of the 37% patients that were found hypertensive, 7.85% (n=19) of the respondents were with previous history of hypertension, whiles overwhelming 29.34% (n=71) of the respondents formed new cases of hypertension. Finding is consistent with [17] but differ in terms of prevalence rate. Finding suggests a high prevalence of hypertension in the district. This also indicates that majority of the residents have hypertension without knowing their status.Hypertension was mostly prevalent among the aged (50 years and above) representing 15.7% of among respondent’s screened positive to hypertension. The mean age of the respondents was 44 ± 17.08. Age was therefore found to have a significant association with hypertension (X2 =12.63, P=0.013). This finding corresponds with finding by Yang et al. [18] which revealed age 25 years and above to be 2.5 times greater risk for hypertension. This suggests that age is a risk factor to hypertension and controlling age can help reduce hypertension. Old age is associated with hypertension because of accumulated fats and lack of exercise among this age category. Gender was also found to be associated with hypertension (X2 = 0.0075, P=0.931). However, majority (21.07%) of respondents with hypertensive status were females whiles their male counterparts scored 16.1%. Finding is inconsistent with the finding revealed by Yang et al. [18] which revealed men to be 2.5 times greater risk for hypertension. Females are emotional as compared to males and they also rely more on sweets and fatty food as compared to male. Sedentary lifestyle is mostly predominant among females as compared to their male counterparts. Respondents with JHS level of education formed majority both among hypertensive and non-hypertensive patients (16.53%) and 26.86% respectively. Education was however not associated with hypertension (X2 =2.54, P=0.637) and this contradicts the finding by Darling [19] which revealed education as a risk factor to hypertension. This finding suggests that respondents are more informed about hypertension. Occupational status was however not associated with hypertension (X2=0.0609, P=0.805) and inconsistent to finding by Darling [19] which found occupation as a risk factor of hypertension. This finding suggests that most of the respondents were active in their day to day activities especially as majority of the respondents were farmers. Family history of hypertension did not have any significant association with hypertension (X2=2.7505, P=0.097). Finding is different from what is reported by Hennekens [20] that family history is associated with hypertension. This finding means that most of the respondents had no family history of hypertension. From the study, 18.60% of the hypertensive respondents were with BMI ranging from 18-24.9 (normal weight), 14.05% with BMI of 25-29.9 (Overweight) and 3.31% with BMI of 30+ (obesity). Meanwhile, there was no association between BMI and hypertension (X2=2.7042, P=0.440) and is inconsistent with results from Turrell et al. [21] which revealed BMI as having association with hypertension. Obesity is a major factor to hypertension as the fats stores is linked to blockages of the arteries and veins. Even though several studies have established a significant relationship between BMI and hypertension which the authors strongly agree. However, the variance between BMI and hypertension in this study was due to the study population and the small sample size.Evidence supports the conclusion that cigarette smoking causes various adverse cardiovascular events and acts synergistically with hypertension and dyslipidaemia to increase the risk of coronary heart disease [20]. Cigarette smoking in this study showed significant association with hypertension (X2=8.431, P=0.0473) as revealed in the study and is in consonance with finding by Hennekens [20] which revealed association between smoking and hypertension. Non-alcoholic intake respondents formed majority (28.51% and 50%) of both hypertensive and non-hypertensive respondents. Alcoholic intake therefore revealed no association with hypertension (X2=0.2897, P=0.865) and contradicts finding that high consumption of alcohol is associated with and a predictive of hypertension [22]. Alcohol is a major cause of hypertension due to its characteristics as energy dense. However, the number of non-alcoholic respondents among respondents screened positive to hypertension formed majority. Stress days showed no association with hypertension (X2=3.4985, P=0.061). Meanwhile, the mean stress was revealed as 4.85±2.24. This finding suggests that stress is not a risk factor considering this study. On physical activities, finding revealed that all 37.19% respondents positive to hypertension were active. Physical activities of respondents therefore had no association with hypertension (X2=1.7986, P=0.180) and this is due to the fact that majority of them were farmers and differs from finding by Rahl [23] which indicated lack of physical activities as a major predictor of hypertension. Salt consumption also had no significant association with hypertension (X2=2.3459, P=0.126) and is inconsistent with finding by Khaw & Barrett-Connor [24] which revealed heavy intake of salt as predictor of hypertension. Salt intake is revealed by previous scholars as risk factor to hypertension, though there was no association between salt intake and hypertension, but 3.3% of those that were positive to hypertension were found consuming higher amount of salt indicating a relationship between salt intake and hypertension. On average respondents were found taken vegetables within 5.49±1.91, meanwhile, finding indicated no association between vegetable intake days and hypertension (X2=2.7379, P=0.254). The mean days of respondents intake of fruit was 4.78±2.24 as overwhelming 16.53% and 29.75% respondents screened with hypertension and without hypertension were taken fruit within 7-8 days. Fruit intake however showed no significant association with hypertension (X2=1.6921, P=0.429). Vegetables and fruits are said to prevent and further reduce hypertension and it is therefore not surprising that the finding is indifferent from what was reported by Drewnowski [25] that vegetables and fruits prevents hypertension and further reduces the systolic and diastolic pressure. Hypertension was found not associated with vegetables and fruits because vegetables and fruits aid the prevention of hypertension. Moreover, vegetables and fruits have no cholesterol content to block the veins and arteries which is associated to hypertension. Commonly used oil was reported significantly associated with hypertension (X2=9.2382, P=0.002), as 30.58% and 40.08% respondents with hypertension and without hypertension and confirms finding by Drewnowski [25] which revealed association between saturated fats and hypertension. Saturated fats solidify at room temperature which means that the probability of causing hypertension is high and therefore confirms its association with hypertension. Furthermore, the study found no association between source of protein and hypertension (X2=4.9691, P=0.083). Meanwhile 16.53% of respondents screened positive to hypertension were using animal as source of protein and contradict the finding by Darling [19] which revealed animal source as a risk factor of hypertension. Majority relying on animal source as protein and been hypertensive means that animal source of protein is a risk factor of hypertension and therefore have to rely more on plant source than the animal source of protein.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study therefore concluded that hypertension is prevalent in Tano North District in the Ahafo Region, Ghana as 37% of respondents were found to be hypertensive. Commonly used oil is associated with hypertension (X2=9.2382, P=0.002), as 30.58% and 40.08% respondents with hypertension and without hypertension were using saturated oil. Hypertension was mostly prevalent among the aged (50 years and above) representing 15.7% of among respondent’s screened positive to hypertension. Cigarette smoking showed significant association with hypertension (X2=8.431, P=0.0473) as well as age has a significant association with hypertension (X2 =12.63, P=0.013).The District Health Directorate and health professional should and Non-Governmental Organizations should embark on monthly outreach screening in aid of determining hypertension among unknown hypertensive residence in Tano North District especially Campso community that was most prevalent and also strengthening health education towards hypertension. Residence should be educated on relationship between saturated oil intake and hypertension in order to reduce hypertension occurrence in the district.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are most grateful to the cooperative respondents that took part in the study, Tano North District Health Directorate for permission and staff of the Public Health Department of Saint John of God Hospital at Duayaw Nkwanta and finally, to Mr Luke Ojo and Dr Emmanuel Adu for their guidance, critique and suggestions made to this article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML