-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2019; 9(1): 7-12

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20190901.02

Willingness and Ability to Pay for Sanitation in Busia

Josphat Martin Muchangi 1, George Kimathi 1, Sarah Karanja 2, Maarten Kuijpers 3, Marjolein Ooijevaar 3

1Amref Health Africa, Nairobi, Kenya (Amref Health Africa Headquarters)

2Amref Health Africa, Nairobi, Kenya (Amref Health Africa Kenya Country office)

3Amref Health Africa, Leiden, Netherlands (Amref Flying Doctors Netherlands)

Correspondence to: Josphat Martin Muchangi , Amref Health Africa, Nairobi, Kenya (Amref Health Africa Headquarters).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

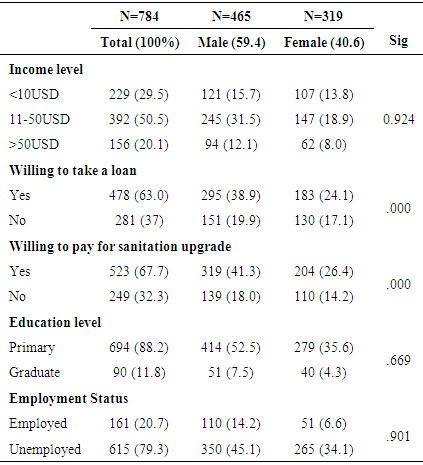

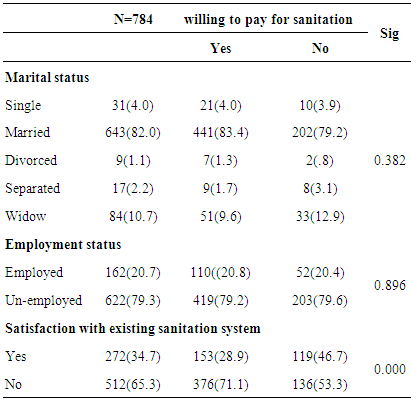

Globally, access to improved sanitation remains a major challenge where about 2.4 billion people still lack toilets. Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are the worst affected where about 800 million people still practice open defecation with remarkable negative health and economic effects. Diarrhoea due to poor sanitation kills more children than HIV and measles together. This study was designed to determine the willingness and ability to pay for safe sanitation by households in Busia County. A cross sectional survey was conducted on 784 households using contingent valuation method. Data was collected using structured questionnaires and both descriptive and inferential statistics were deduced. A model fit and economic modelling was performed to determine willingness and ability to pay. A total of 465(59.4%) male and 319(40.6%) were female heads were interviewed. Slightly more than a half of the respondents earned between 10-50 dollars in a month with no significant difference between male and female (P=0.924). About 487 (63%) were willing to take a sanitation loan and about 67.7% of the respondents were willing to upgrade their sanitation system. The willingness to take a loan and upgrade the existing sanitation differed significantly between male and female respondents (P=0.000). The study finds that dissatisfaction with the existing sanitation significantly affected the willingness to pay (P=0.000). The willingness to pay was high with about 68% of the population expressing interest to take a loan for sanitation. However, only about 10.1% of the population were able to pay for sanitation at the cut off price of 415 dollars. The study concludes that the market potential for sanitation is huge. We further recognize the role of various sanitation financing instruments including loans as the sustainable means of promoting access to improved sanitation.

Keywords: Sanitation, Willingness to pay, Ability to pay

Cite this paper: Josphat Martin Muchangi , George Kimathi , Sarah Karanja , Maarten Kuijpers , Marjolein Ooijevaar , Willingness and Ability to Pay for Sanitation in Busia, Public Health Research, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 7-12. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20190901.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The UNICEF/WHO Joint Monitoring Programme for water supply and sanitation (JMP) estimates that 2.4 billion people globally lacked improved sanitation facilities sources in 2015 [1]. This is not completely different for Kenya with only 30% of the population accessing improved sanitation. Poor sanitation is associated with among others diarrhoea diseases, the transmission of helminths and in the end affects the nutrition status of children. It is estimated that diarrhoea kills children three times more than HIV, TB and Malaria [2, 3]. Further, inadequate sanitation is associated with loss of time spent out of productive labour or seeking a place to defecate leading to overall decreased economic productivity resulting. It is further estimated that Kenya loses of an estimated twenty seven (27) billion shillings annually due to poor sanitation [4]. Community led total sanitation methodology (CLTS), a non-subsidy based approach, was developed to empower communities to quit open defecation practices [5]. This method has since demonstrated undisputed effectiveness in improving sanitation access and transforming communities hygiene behaviours [6-8]. Inspired by the efficacy of promoting sanitation through community led total sanitation methodology, the Ministry of Health adopted CLTS as the mainstay strategy for scaling up sanitation in Kenya [9, 10]. This was part of the government strategy to ensure accelerated access to basic sanitation and was a radical departure from the traditional subsidy based programs.While CLTS promotes access to basic sanitation, latrines built through this process are basic and do not meet the criteria of improved sanitation. It is assumed that an open defecation free (ODF) community will further rise up the sanitation ladder towards safely managed sanitation with sanitation marketing as an important driver. Sanitation marketing envisages that households and communities will mobilize financial contribution for improvement of sanitation facilities and this is influenced by the willingness and ability to pay for sanitation systems of choice. In this context, this study was conducted to estimate the market opportunities for newly developed sanitation systems among rural populations of Busia. As this was the first county in Kenya to be declared ODF in 2015 from which point sanitation marketing is introduced to further increase the service levels in the country.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

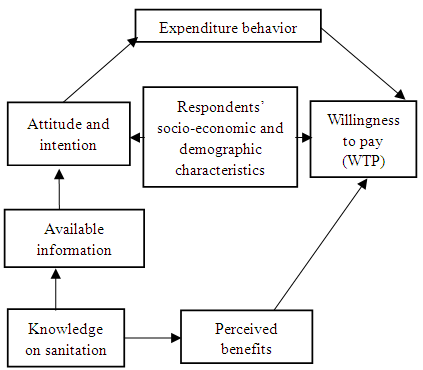

- When introducing a new service it is not so much a problem to assess the costs. Much more complicated is understanding the willingness to pay (WTP) for these new goods or services. The WTP evolves out of the assumption that consumers make rational decisions on their expenditures while being faced with budget restriction. In return for these expenditures a collection of goods and services (consumption bundle) is purchased that serve a certain use in the eyes of the consumer (utility). When a new good or service is introduced, the successfulness depends on the increase in utility it represents in comparison with the current bundle while taking into account the change in expenditures. The WTP is exactly this room in expenditures set against the improvement of utility. The main assumption in willingness to pay studies is that individuals willing to pay, somehow, have the ability to pay [11].As the figure below shows, the WTP is largely dependent on the perception by consumers on the price and the unique value effect to improved sanitation, household expenditure and the social demographic characteristics.

| Figure 1. Theoretical framework for willingness and ability to pay for improved sanitation |

2.2. Study Area

- The study was conducted in Busia County located in Western most part of Kenya. It lies between latitude 0° and 0° 45 north and longitude 34° 25 east and covers an area of 1694.5 km2 and has seven sub-counties namely: Busia, Nambale, Butula, Bunyala, Samia, Teso North and Teso South [13]. The county is a beneficiary of the Royal Dutch Government funding whose goal is to sustainably expand access to improved sanitation through financial inclusion instruments.

2.3. Study Population

- The study population was composed of adult male and female household heads of families. Household headship is historically associated with economic provision for families a position mainly occupied by men. As the household providers, they are equally responsible for taking decisions on how to spend the household income.

2.4. Study Design

- The study design was a cross sectional study and targeted the household heads or decision makers in the households.As derived from the theoretical framework, the study employed contingent valuation method (CVM) an economic survey technique used to elicit people’s preferences when market for a good or service is absent, imperfect or incomplete [14-16]. CVM has been used by environmental economists for estimation of benefits related to quality and quantity improvement of public goods [17]. The data collected was to estimate the demand for improved sanitation systems known as the ventilated improved double pit latrine (VIDP) [18]. The study questionnaire was designed to collect data which would allow estimation of payoff rates for sanitation loans based on declared household’s income and expenditures. Close ended questions were preferred since they minimize the varied and unspecified answers and minimize difficulties in answering as supported by other literature [19]. The survey adopted a hybrid of dichotomous and closed ended questions to increase the reliability of the answers while keeping the respondents focused on the question. From the field trials, the cost of a VIDP was estimated at USD 415 but in the bidding, the highest price was set at USD 519 which was 0.25 times higher than the actual to factor in price variations due to spread geographical complexities.

2.5. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

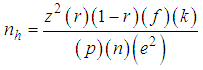

- A sample size of 784 was calculated based on formula [20].

Where:nh: is the parameter to be calculated and is the sample size in terms of number of households to be selected:z: is the statistic that defines the level of confidence desired;r: is an estimate of a key indicator to be measured by the survey;f: is the sample design effect, deff, assumed to be 2.0 (default value);k: is a multiplier to account for the anticipated rate of non-response;p: is the proportion of the total population accounted for by the target population and upon which the parameter, r, is based; n: is the average household size (number of persons per household); e: is the margin of error to be attained.The values for some of the parameters were as follows:The z-statistic used is 1.96 for the 95-percent level of confidence. The default value of f, the sample design effect, was set at 2.0. The non-response multiplier, k, of 10% which is applicable in developing countries was applied; a value of 1.1 for k, therefore, was chosen.Combinations of multi-stage cluster, systematic and simple random sampling techniques were employed to identify the respondents (probability sampling techniques at every stage) [21]. In the first stage, sub-locations were chosen from all the sub-counties as the primary sampling unit (PSU) using proportion to size method. Target sub-locations were chosen using simple random methods. The selection of specific villages (as the secondary sampling unit) from the selected sub-locations was done using simple random sampling. The last stage of sampling involved the application of systematic sampling method with the interval kth being determined by dividing the number of households in that village by ten. The starting direction was determined randomly by toasting a pen and the direction in which it pointed was followed. The right hand side house in the direction which the enumerator was facing became the first household to be interviewed. This process was followed for all other subsequent houses.

Where:nh: is the parameter to be calculated and is the sample size in terms of number of households to be selected:z: is the statistic that defines the level of confidence desired;r: is an estimate of a key indicator to be measured by the survey;f: is the sample design effect, deff, assumed to be 2.0 (default value);k: is a multiplier to account for the anticipated rate of non-response;p: is the proportion of the total population accounted for by the target population and upon which the parameter, r, is based; n: is the average household size (number of persons per household); e: is the margin of error to be attained.The values for some of the parameters were as follows:The z-statistic used is 1.96 for the 95-percent level of confidence. The default value of f, the sample design effect, was set at 2.0. The non-response multiplier, k, of 10% which is applicable in developing countries was applied; a value of 1.1 for k, therefore, was chosen.Combinations of multi-stage cluster, systematic and simple random sampling techniques were employed to identify the respondents (probability sampling techniques at every stage) [21]. In the first stage, sub-locations were chosen from all the sub-counties as the primary sampling unit (PSU) using proportion to size method. Target sub-locations were chosen using simple random methods. The selection of specific villages (as the secondary sampling unit) from the selected sub-locations was done using simple random sampling. The last stage of sampling involved the application of systematic sampling method with the interval kth being determined by dividing the number of households in that village by ten. The starting direction was determined randomly by toasting a pen and the direction in which it pointed was followed. The right hand side house in the direction which the enumerator was facing became the first household to be interviewed. This process was followed for all other subsequent houses. 2.6. Statistical Analysis

- Data was analysed using SPSS version 19 with significance set at 0.05. Descriptive statistics were run to determine frequencies and percentages for different variables. For inferential statistics, association for all categorical variables was determined by Chi square test and binary logistics regression. By use of economic modelling, the willingness and ability to pay was deduced.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

- Ethical and Scientific approvals for this study were sought and provided by Ethics and scientific Review Committee (ESRC) of Amref Health Africa. Administrative consent was sought from Government officials in Busia. During the study, participants were informed about the objectives of the study and informed verbal consent to participate was sought based on their free will to do so. Confidentiality was assured and right to withdraw at any point of the study was explained.

3. Results

3.1. Determinants of Willingness to Pay for Sanitation

- A total of 784 households participated in this study of which 465(59.4%) were male and 319(40.6%) were female. Slightly more than a half of the respondents earned between 10-50 dollars in a month with no significant difference between male and female (P=0.924). About 487 (63%) were willing to take a sanitation loan and about 67.7% of the respondents were willing to upgrade their sanitation system. The willingness to take a loan and upgrade the existing sanitation systems differed significantly between male and female respondents (P=0.000). Majority 694 (88.2%) had attained primary but only 161 (20.7%) had formal employment. There was however no significant difference in education and employment status between men and women with P values of 0.699 and 0.901 respectively.

|

|

3.2. The Willingness and Ability to Pay for Sanitation

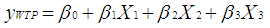

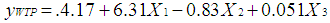

- The willingness and ability to pay was determined by empirical regression equation:

Where,

Where,  Is the ability to pay is

Is the ability to pay is  Is willingness to take a loan

Is willingness to take a loan  Is the option of preference

Is the option of preference  and

and  are parameter estimators

are parameter estimators  Equation 1) above explain that if all factors are held constant, 63.1% of the variance in the willingness to pay is directly explained by the willingness to take a loan. About (8.3%) of the willingness to pay is indirectly explained by the proportion of the income to be spent on the sanitation based on expenditure cut off. We also note that 5.1% of the variance explained in the willing to pay was affected by the preferential option of the payable amount per month. The demand function was further developed from the relationship between willingness to pay and the amount people can pay per month. The demand function was developed from the equation below:

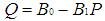

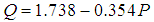

Equation 1) above explain that if all factors are held constant, 63.1% of the variance in the willingness to pay is directly explained by the willingness to take a loan. About (8.3%) of the willingness to pay is indirectly explained by the proportion of the income to be spent on the sanitation based on expenditure cut off. We also note that 5.1% of the variance explained in the willing to pay was affected by the preferential option of the payable amount per month. The demand function was further developed from the relationship between willingness to pay and the amount people can pay per month. The demand function was developed from the equation below: Where

Where  is the constant and

is the constant and  is the estimator for P which is the amount people can pay per month. We found that

is the estimator for P which is the amount people can pay per month. We found that  This meant that if you raise the price of the toilet by 1% the willingness to pay would drop by 35.4%. We found that

This meant that if you raise the price of the toilet by 1% the willingness to pay would drop by 35.4%. We found that  was 0.101, which means based on cutoff amount a person is expected to pay per month to complete the whole amount of the sanitation (latrines), only 10.1% of the whole population is willing and able to pay.

was 0.101, which means based on cutoff amount a person is expected to pay per month to complete the whole amount of the sanitation (latrines), only 10.1% of the whole population is willing and able to pay. 4. Discussions

- Since the year 2000, the proportion of people around the world using improved sanitation facility increased from 59 to 68%; a slow rate given the ambitions of the sustainable development goal 6 by the year 2030 [22]. Demand creation and behaviour change approaches have increasingly taken centre stage in sanitation promotion effectively diminishing the traditional focus of merely constructing toilets. Evidence shows that effectiveness of demand creation coupled with behaviour change alone as a means of scaling up sanitation to the poor is doubtable [23]. One of the principal constraint to sanitation improvements is inadequate capital to construct toilets by households. Arguably, financial inclusion through credit is one of the innovative financing that would complement the demand creation efforts by improving households’ liquidity to purchase the toilet [24]. The willingness and ability to pay for sanitation by households remains un-clear to the promoters of financial inclusion. Without knowledge on the willingness and ability to pay, demand creation targeting may become complex leading to wastage in unfocussed and expansive campaigns.This is one of the few willingness and ability to pay for sanitation studies that have been conducted countrywide in similar context. These findings suggest that rural households were willing to pay for sanitation improvement with appropriate financial inclusion models such as loaning. This perhaps may provide insights into construction of sanitation promotion model that may break the barriers to accelerated access to improved sanitation is attainable. This study shows high self-reported willingness to pay for upgrading sanitation of up to 63% of the target population for a latrine costing 420 dollars. This corroborates findings of nearly similar study conducted in Uganda [25]. Notably, the overwhelming self-reported willingness to pay for sanitation should be considered based on hypothetical scenario for value elicitation on condition that households would be required to pay monthly instalments instead of lump sum amounts. The other aspect that might have led to this very high positive response on the willingness to pay was the mass transactional demand creation activities through community led total sanitation that had been carried out in the entire county. Community led total sanitation has generally been shown to increase demand for sanitation [26]. The significant difference between male and female in willingness to take a loan may explain the gender power variance predominant within the community [27]. This also explain the most appropriate customer to target with sanitation promotional and sales messages.The study strived to demonstrate that willingness to pay is determined by select socio-demographic variables (independent) such as marital status, employment status education level of the household head, satisfaction with the current latrine and sex of the household head. Household expenditure on sanitation was the only significant determinant of willingness to pay while other factors were relatively insignificant. We find that willingness to pay is in no way affected by marital status or employment status of the household. Chi square tests were run to determine the statistical significance. This corresponds to a study conducted in Vietnam within the same context [28]. In the past, loaning through micro-financing to otherwise financially excluded households is largely associated with income generating activities. There is gradual departure from the classical approach of focusing on income generation to social protection or lending to enhance access to social goods and services. The value proposition in this case is that access to improved sanitation generates direct health benefits minimizing household expenditure on treatment of the associated illness. Due to massive promotion of sanitation loans by financial institutions, communities in Busia are likely to report high demand for sanitation loans. This study finds that willingness to pay is largely driven by availability of a loan with about 63% of the respondents reporting that they would gladly opt for a sanitation loan. In Busia loans for sanitation present new ideas and dynamics for sanitation financing that could accelerate access to sanitation as alluded by other studies [29]. The study takes note of the sensitivity of the sanitation market to price variation. We note that an increase of 1% in pricing would lead to a market loss of about 35%. We assume that willingness to uptake sanitation is not only sensitive to pricing alone but to other factors such as perceived norms, participatory persuasion, and positive and negative reinforcements that may accompany promotion of the toilet. Based on the cut off, we find that essentially only about 10% of the total population in Busia would effectively afford to pay for a sanitation system that costs $420. The cost of building sanitation has been in cases found to be prohibitive [30]. To attain the ambition of the sustainable development goals calls for concerted effort to make the markets work for the poor by lowering the cost of sanitation. Firstly, efforts to develop the supply side in sanitation should be increased. Modularization has been known to reduce complexity of designs and increase efficacy which should be the programming aim [31]. Additionally, setting up of mass production centres of different sanitation parts overs leverage on economies of scale and has direct potential in lower cost of production [32]. This presumably will reduce the overall cost of sanitation and in turn increase the willingness and affordability of sanitation contributing to attainment of desired inclusive scale.

5. Conclusions

- This study concludes that the potential for sanitation market is huge. If properly harnessed and manipulated, commercial orientation of sanitation market may contribute to attainment of the ambitions of SDG for sanitation. However, development of these markets need to involve multiple players supporting each other with the aim of markets work for the poor. Since availability of loans are key determinant of willingness to pay, direct involvement of financial institutions in the design and marketing of sanitation product will be a key consideration. Since this research finds that ability to pay for sanitation is highly price sensitive, sanitation entrepreneurs and promoters need to continually work towards reducing the cost of sanitation products.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This work was made possible through the financial support of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through Netherlands business Agency (R.V.O). We are in a special way indebted to Mr. Ambrose Fwamba, who by all means ensured smooth flow of data collection processes; reaching every sampled household in the rural Busia. Lastly we acknowledge the efforts of every data collector for diligently engaging the interviewees in providing accurate information for the study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML