-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2019; 9(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20190901.01

Male Involvement in Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness: Perspectives from Rural and Urban Postpartum Women of Navrongo

Titi Addebah Gregory1, Kuganab Lem Robert2

1Community Health, School of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University for Development studies, Tamale, Ghana

2Public Health, SAHS/UDS School of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana

Correspondence to: Titi Addebah Gregory, Community Health, School of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University for Development studies, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) is a key strategy in safe motherhood programmes that aim at reducing delays in reaching professional care and improving the use and effectiveness of key maternal and newborn health services. The aim of the study was to determine the degree to which male counterparts got involved in birth preparedness and complication readiness among postpartum women in rural and urban communities of the Kassena-Nankana municipality of Ghana. A cross-sectional descriptive study employing questionnaires and focus group discussions was used for the data collection and Stata 14 used for the analysis. Of the three hundred and eighty-eight (388) pregnant women interviewed, there was ANC coverage of 99%. A composite index with ten indicators yielded 72% and 56% averages for urban and rural male partner involvement in BPCR practice ranging from low involvement in decision making to high involvement in supporting ANC, skilled birth and PNC related utilization. About 97% urban and 85% rural women gave birth with skilled attendance. Also, educational level, place of residence, an experience of stillbirth/miscarriage and socio-economic status of respondents were significantly associated with the use of skilled delivery services. Many men in urban than rural communities were involved in BPCR utilization. Conscious efforts should be made by the health ministry for the education of male partners on the need to be involved in BPCR uptake across the municipality.

Keywords: Birth preparedness, Male involvement, Rural and urban

Cite this paper: Titi Addebah Gregory, Kuganab Lem Robert, Male Involvement in Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness: Perspectives from Rural and Urban Postpartum Women of Navrongo, Public Health Research, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20190901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Male partner/husband involvement is crucial for the existence, maintenance and care of pregnancy, and the newborn at large. Male involvement in pregnancy and childbirth reduces negative maternal health behaviours, risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and infant mortality as well. It also reduces maternal stress (emotional, logistical and financial support), increases uptake of prenatal care, leads to cessation of risk behaviours (such as smoking) and ensures men’s involvement in their future parental roles from an early stage [1]. The practice of BPCR could be affected by male partner participation because husbands are considered the most influential decision-makers and as the key members of the family [5]. They decide the timing and conditions of sexual relations, family size, and whether their spouse will utilize available health care services [6]. This was clear in Ethiopia, where studies showed that one of the factors of affecting antenatal care attendance was 15.5% husband’s disapproval for it and just 21% of the pregnant mother were accompanied by their husbands to the antenatal clinic. In Western Kenya, about 45% of husbands considered child-birth as a women’s affair without husbands’ participation. Studies in Nigeria reveal as much as 97.4% males/husbands were encouraging their wives to attend antenatal clinic, 96.5% paying antenatal service bills, and 94.6% paying for transport to the clinic, 72.5% accompanying their wives to the hospital for their last delivery and 63.9% being present during the delivery itself. Another study in Northern Nigeria also revealed that 32.1% of men accompanied their spouses for maternity care, 77.1% provided money for transport and medication and 13.0% accompanied their spouses to the hospital for ANC. During the delivery 71.4% provided money for transport/drugs, 18.7% personally accompanied their spouses to the hospital and 3.7% donated blood. During postnatal care, 80.4% of husbands gave money for transport/drugs with only12.0% accompanying their spouses and 1.3% donating blood somewhat maintaining the trend after delivery [5]. In Ghana, however, there is limited research on male involvement during pregnancy through to childbirth amidst the various safe motherhood interventions put in place by the government despite the much-dominated influence men have in childbearing issues in particular. This paper documents the male counterpart’s influence and contribution to the uptake and utilization of BPCR practices on the part of their women in rural and urban settings of northern Ghana.

2. Methodology

- The study area was the Kassena-Nankana Municipality in the Upper East Region of Ghana. The municipality has a population estimated to be 113,950 with a population density of 92 persons per square kilometre. Population of WIFA is 26,550 (23% of total population) while that of children 0-59 months are 51,164 representing 45% of the total population. Also, children from 0-23 months, form 15% (7675) of the under-five age. The population is dispersed in ninety-nine (99) communities of which majority are rural and only 13% of the population lives in town. Only Navrongo (the capital) can be classified as an urban settlement with a population of twenty thousand (20,000) inhabitants. The major occupation is agriculture, employing about 68.7 per cent of the total labour force; production/transport operators and labourers constitute 10:4 per cent, Sales workers (9.2%), service workers (5.6%), Administration / Managerial workers (0.1%), professional technical workers (3.5%) and others (1.0%) [3]. The municipality is made up of seven sub-municipalities with twenty-four health facilities. This is made up of one municipal hospital, two health centres, two private clinics, one CHAG facility and eighteen functioning CHPS zones [3].

2.1. Study Population

- The main target population was women who have recently given birth. They were the direct beneficiaries of the support from men and users of BPCR services and could better assess the level of their male counterpart’s involvement in BPCR uptake and practices. Women whose biological children were less than twenty-four (24) months were considered recently given birth for the purposes of this study. Participants were drawn from the Navrongo Central (urban), Vunania (rural; about 10 km away from the district hospital) and Manyoro (rural; about 25 km away from the district hospital) sub-municipalities. Manyoro in particular has its principal motorable road passing through another district before entering Navrongo town where the municipal hospital is located.

2.2. Study Design

- A cross-sectional study design was employed using both quantitative and qualitative methods to gather the data. The inclusion criterion was post-partum women, resident in the selected communities from conception to delivery of the current child.

2.3. Sample Size

- The sample size was calculated using a formula adopted from the Service availability and readiness assessment (SARA) implementation guide, developed by WHO, [8] for the overall study and segregated to cater for urban and rural communities based on weighting. The sample size was three hundred and eighty-eight (388) drawn from three out of the seven sub-municipalities.Also, six focus groups (FGDs) were conducted; two in each study sub-municipality to get in-depth information on male partner involvement in BPCR practices in particular. Participants in each FGD included elders/chiefs, assembly members, health volunteers, women who were married, single mothers, women who delivered at health facilities, at home and those also had history of miscarriage (s), TBAs and married men.

2.4. Sampling Technique

- Multi-stage sampling technique was used to select the study sample. Two out of the six rural sub-municipalities were randomly selected. The only urban sub-municipality was purposely chosen. Lists provided by the health facilities in the selected areas on post-partum women were used to sample participants on systematic bases. There was local weighting (proportional to size) among the listed communities that visited a particular facility. Only one woman was interviewed per a house. If a selected member is not available / non-compliant, the one next to her in the list was interviewed while not distorting the parental systematic order. On the part of focus group discussants, consultation with the chief, assembly person and the health volunteer was done to arrive at the people that should represent the respective participants; elders/chiefs, assembly members, health volunteers, women who were married, women who were single, and delivered in health facilities, home and those having history of miscarriage (s), TBAs and married men.

2.5. Data Collection Tools

- Semi-structured interview questionnaire adopted from the safe motherhood questionnaire developed by the maternal and neonatal health program of JHPIEGO [7] was used to collect the information from post-partum women. The focused Group Discussion guide was used to solicit for information on community-level engagement on BPCR practices.

2.6. Access and Participant’s Protection

- This research is part of a thesis research work of the first author entitled “Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness: A comparative study among post-partum urban and rural women in the Kassena-Nankana Municipality of Ghana”. Participants were told of the purpose of the study (academic) and their involvement was voluntary. They were assured that the information provided would be kept highly confidential and would be used solely for the purpose for which it was collected.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

- Majority of the women were between the ages of twenty (20) and thirty-four (34) years (80%), 9% constituted women under the age of twenty years and 11% constituted women who were thirty-five (35) years and above. More than as twice women in the urban (9 women) setting gave birth in the rural areas (21 women from rural) for those who were less than twenty years of age. Many more women in the urban area (extra 20 representing 8.75%) than in the rural areas gave birth between age twenty (20) and thirty-four (34) years. Generally, 88.9% of the respondents in the study were married, 8.9% were single, and those who were divorced, separated or widowed had proportions 0.8%, 0.5%, and 0.8% respectively. The proportion of the married respondents was higher in the urban communities (91.2%) than in the rural communities (86.4%). Majority of the respondents were Christians, comprising an overall 82.6% Christian population with about 87% in the urban communities and 78% in the rural communities. Islam was represented 13.2% in the urban communities and about 1.6% in the rural communities and an overall representation of 7.3% in this study. Traditional religion was most prominent in the rural communities with a proportion of 18.9%.

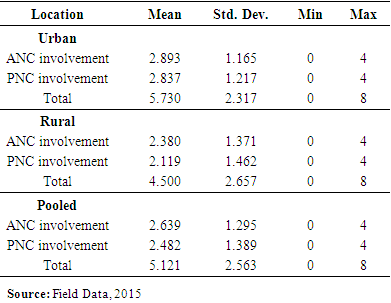

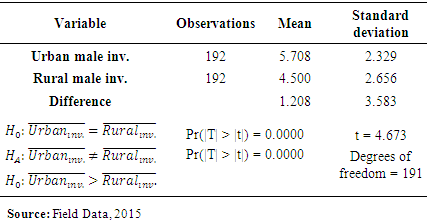

3.2. Male Involvement during Pregnancy, Birth and Post Delivery

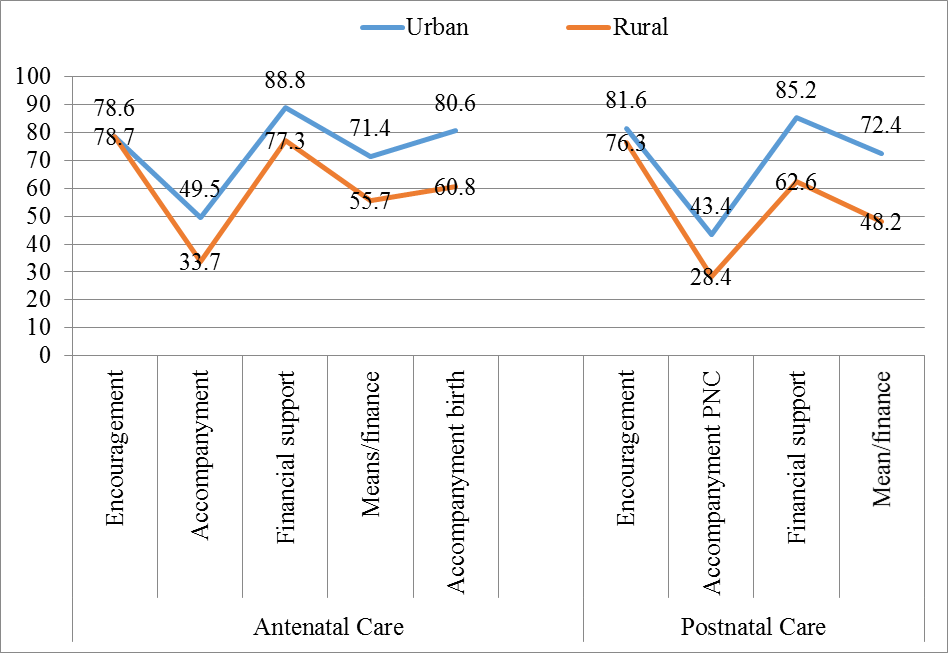

- Of a total of 196 and 192 urban and rural post-partum women respectively, the proportion of women who agreed that husbands/partners should be involved in pregnancy and childbirth issues was high for both urban (92.3%) and rural (97.1%) areas.The following were the other nine areas that males where involved in regarding BPCR; encouraging or reminding the woman to seek ANC, usually accompanying her to ANC service, usually providing her with financial support for ANC, usually providing her with means/financial support for transport to attend ANC, accompanying her to where she gave birth, encourage/reminding her to seek PNC services after delivery, usually accompanying her to attend PNC services, usually providing her with financial support for PNC services and usually providing her with means/financial support for transport to attend PNC services.The proportion of women who had encouragement or reminder to seek ANC services was 78.6% in the urban areas and 78.7% in the rural areas, 49.5% of urban women and 33.7% of rural women said their male partners usually accompany them to seek ANC services. 88.8% of urban women and 77.3% of rural women said their male partners usually provide means of transport and financial support for transport to seek ANC services. With regards to male involvement during birth, 80.6% of urban women said their male partners accompany them to the facility to give birth compared to 60.8% in the rural areas. Though the data showed many urban women (49.5%) than rural (33.7) were accompanied by the male partners, in a focus group discussion at the urban centre, women argued that some of the male partners give “lift” to their women to the health centres and not that they have accompanied the females.

| Figure 1. Level of male involvement during antennal care and postnatal care |

|

|

4. Discussion

- In total, 88.9% of the respondents in the study were married, 8.9% were single, and those who were divorced, separated or widowed had proportions 0.8%, 0.5%, and 0.8% respectively. The high number of married women could be attributed to mothers probably thinking that caring for pregnancy/children required the attention of both parents which marriage could guarantee though childbearing outside marriage is not uncommon in Ghana.

4.1. Determinants of BPCR Practices

- Making a decision to seeking care, where and when or otherwise is very fundamental though it also roots in the severity of the health problem. Also, who the decision maker is should also be considered due to their influence. [5], noted that birth preparedness is employed in implementing safe motherhood programs, it may be affected by males; the most influential decision-makers of the family in most cases. [6]. also outlined males’ role in deciding the timing and conditions of sexual relations, family size, and whether their spouse will utilize available health care services. This was evident in Ethiopia, where one of the factors affecting antenatal care attendance was 15.5% husband’s disapproval for it [6]. Contrary to the above, results of this study showed that women were the majority (37.3%) to make their own final on where they would give birth, followed by health workers (nurses, midwives, and health research workers) with 34.7%. Husbands’ making of decisions was third place with 16.8%. Overall, there was as high as 88.8% set decision making on where to give birth prior to delivery. This outcome is consistent with the findings in Tanzania by Urassa et al., [2] who also had up to 86.2% of their sampled women decisions made on the place of delivery prior to birth. The high percentage of women making decisions on where they would give birth could be attributed to their prior exposure to BPCR services during ANC and past delivery experiences. Also, having many women stating of health workers as those who decided where pregnant women should give birth could also be attributed to the advice usually given to pregnant women during ANC and much particular of those women who reported ill health to the health workers. Overall, this has contributed to 96.9% and 85.3% urban and rural women respectively giving birth with skilled professional/attendant at a health facility far exceeding the 57% national health facilities based deliveries in 2008 [4].

4.2. Male Involvement

- Birth preparedness is a relatively common strategy employed in implementing safe motherhood programs which may be affected by male partner participation because husbands are considered the most influential decision-makers and as the key members of the family in some settings. The proportion of women who agreed that husbands or male partners should be involved in pregnancy and childbirth issues was high for both urban (92.3%) and rural (97.1%) areas. This in part, according to [6] male partners or husbands decide the timing and conditions of sexual relations, family size, and whether their spouses will utilize available health care services. Aside decision making, husbands or male partners could involve in dissipation of resources to enable women to seek for care etc. According to Kaye [1], the involvement of a male partner/husband is crucial for the existence, maintenance and care of pregnancy and the newborn at large. Male involvement in pregnancy and childbirth reduces negative maternal health behaviours, the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and infant mortality as well. It also reduces maternal stress (emotional, logistical and financial support), increases uptake of prenatal care, leads to cessation of risk behaviours (such as smoking) and ensures men’s involvement in their future parental roles from an early stage. This study revealed that 78.6% urban and 78.7% rural women had encouragement or reminders to seek ANC services from their husbands and 49.5% of urban women and 33.7% of rural women had their male partners usually accompanying them to seek ANC services. In the focus group discussions, women argued that some of the male partners merely gave “lift” to their women to the health centres and not that, they have accompanied the females. This means that at least 30% less men accompany their female partners than those who reminded/encouraged their women to seek care out of the 99% of women who utilized ANC services. Overall, not up to half of the male partners accompanied their women for ANC services. However, little over 80% (88.8% of urban and 77.3% of rural) male partners usually provided means of transport or financial support for transportation to their women to seek ANC services. When it came to delivery, many men attached seriousness to it and accompanied the women than it was in the case of ANC attendance. About 80.6% and 60.8% of urban and rural women said their male partners accompanied them to the facility to give birth. Similar studies conducted by [5] somewhere in Nigeria, indicated as much as 97.4% males/husbands encouraged their wives to attend antenatal clinic, 96.5% paying antenatal service bills, and 94.6% paying for transport to the clinic, 72.5% accompanying their wives to the hospital for their last delivery and 63.9% being present during the delivery itself. Though these Nigerian findings on the average are better than was found in this Navrongo study, another study in Northern Nigeria revealed an opposite outcome where only 32.1% of men accompanied their spouses for maternity care, 77.1% provided money for transport and medication and 13.0% accompanied their spouses to the hospital for ANC. During the delivery, 18.7% personally accompanied their spouses to the hospital [5]. These differences could be attributed to the socio-cultural beliefs and how men in each of these areas also fend for the livelihood or survival of their families. However, it is clear from the three studies that, men attached much attention and accompany women during delivery than ANC attendance as depicted by a general increase in trend of the proportion of men accompanying their women for the two maternal care services.For male involvement in PNC services, the proportion of women who had encouragement or reminders to seek PNC services after delivery was 81.6% in the urban areas and 76.3% in the rural areas, 43.4% of urban women and 28.4% of rural women said their male partners usually accompany them to seek PNC services. 85.2% of urban women and 62.6% of rural women said their male partners usually provide means of transport and financial support to seek PNC services. Contrasting the behaviour of men during ANC and PNC, the trend in each parameter is generally similar. However, many men accompany the women during pregnancy for ANC services (49.5% urban and 33.7% rural) than PNC services (43.4% urban and 28.4% rural). Also on men involvement especially in accompanying women for ANC and PNC services, all four focus groups in rural Navrongo mentioned designated places within the communities where pregnant women and post-partum women meet monthly for ANC and child welfare clinics (CWCs)/PNC services usually pre-arranged by health workers and facilitated by volunteers and traditional authorities. By this arrangement, the distance of travel by the women is reduced and the women usually move in groups/pairs. This could limit the involvement of men to follow them to such centres which are at their doorsteps.

5. Conclusions

- Though husband or male partner involvement in BPCR practices was considered to be important, men involvement fluctuated for the various indicators used, from low involvement in decision making to high involvement in supporting ANC, skilled birth and PNC related utilization. The building of health compounds (CHPS) has contributed a lot in the uptake of BPCR practices and the health ministry and other partners should replicate the concept in a faster pace to enhance maternal and child health especially in rural areas.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML