-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2018; 8(5): 106-114

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20180805.02

Women’s Empowerment and Associated Factors on Contraceptive use in Sheka and Bench Maji Zone, South West Ethiopia

Tesfaledet Tsegay

Msc in Biostatistics, Department of Statistics, Mizan Tepi University, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Tesfaledet Tsegay, Msc in Biostatistics, Department of Statistics, Mizan Tepi University, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study seeks to examine the associations between women’s empowerment and associated factors on contraceptive use in Sheka and Bench Maji zone. A community based cross-sectional study design was conducted from August 10-20, 2016 and the source populations were all married women or who are living with a partner. Nine hundred ninety four women were selected using single population proportion technique. The outcome of interest in this analysis was use of any contraceptive method. Factor analysis was employed to determine theoretically meaningful dimensions of empowerment from seventeen components. The corresponding empowerment factor scores, socio-demographic characteristics, and gender related variables were used as independent variables for further analysis in a Binary logistic regression analysis. In this study 393(39.5 %) women reported to be use of any contraceptive method at the time of interview. In the final Binary logistic regression model that included the indicators of women’s empowerment, dimensions representing independent socio - economic decision, attitude towards domestic violence and Attitudes toward refusing sex were positively associated with contraceptive use except women’s attitudes toward refusing sex. Moreover, women discuss about family planning with health profession (OR=3.067, 95% CI: 2.099, 4.481), women attain better education level (OR=1.467, 95% CI: 1.019, 2.138), partner permit family planning (OR=2.870, 95% CI: 1.702, 4.839) and living in urban area were more likely influence on contraceptive use. Finally our result suggest that different targeting strategies to improve women’s use of contraception, as well as men’s awareness and involvement in family planning via women’s empowerment in Sheka, Bench Maji and Keffa zone, South West Ethiopia.

Keywords: Empowerment, Contraceptive use, Women

Cite this paper: Tesfaledet Tsegay, Women’s Empowerment and Associated Factors on Contraceptive use in Sheka and Bench Maji Zone, South West Ethiopia, Public Health Research, Vol. 8 No. 5, 2018, pp. 106-114. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20180805.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Women’s empowerment is defined, “A process by which those who have been denied the ability to make a strategic life choices acquire such ability”. Male participation and acceptance of changed roles are essential for women’s empowerment [1]. Substantial research has examined the relationship between women’s empowerment and their reproductive health. Research generally finds that women’s empowerment is associated with contraceptive use. Some scholars propose that women’s empowerment increase with education and economic status and thereby influences fertility [1, 2]. Family planning also has significant economic benefits for families and for society as a whole (Gribble, 2012). By slowing the growth of a population, women have more earning potential and families are able to devote more resources to each child, resulting in reductions of poverty [3, 4]. Despite the known benefits of family planning, globally more than 120 million women aged 15 to 49 who are married or in a union have an unmet need for family planning [5]. Accordingly, in many developing countries, most of decisions regarding sexual activity, fertility, and contraceptive use are made by men [6].Currently, family planning service is offered as free of charge in both governmental and NGO health facilities in Ethiopia, including hospitals, clinics, health centers and health stations. However, according to the result of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey which is conducted in 2011, Ethiopia is among countries with low contraceptive prevalence rate 29%, 20% and 57% among married women, all women age 15-49 and sexually active unmarried women, respectively, at national level. In addition, according to EDHS result the prevalence rate of use of any contraceptive method varies notably by region, ranging from 63 percent in Addis Ababa to 4 percent in the Somali region, and 25.8 percent in the SNNP region [7].Factors that influence contraceptive use are multifaceted and challenging. Different studies show that socio-demographic, socio-cultural, socio-economic [8] and women’s empowerment [9, 10] factors mostly affected women’s knowledge and use of contraception. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest average fertility rate in the world. In 2009 the total fertility rate (TFR), or the average number of births per woman, was 5.1 more than twice that in South Asia (2.8) or Latin America and the Caribbean (2.2). Similarly he average contraceptive prevalence rate (22%) is less than half that of South Asia (53 percent) and less than a third that of East Asia (77%) [11]. Although many United Nations member countries, particularly those in the developed world, have strong family planning programs, this is not the case in Sub-Saharan Africa countries including Ethiopia, where despite a rise in contraceptive prevalence, many women continue to have unmet need for contraception [5]. The resultant high fertility is associated with high levels of maternal mortality, especially among the poorest communities.In Ethiopia, women’s participation in their own matters and women’s benefit from social, economic and political spheres is low. Traditional, social and economic values constrain the rights of women and their opportunities to direct their own lives or participate in and contribute to community and national development [12].A study conducted by Birhan research and development consultancy in four region of Ethiopia (Amhara, Oromia, SNNPR and Tigray) show that current use of modern contraceptive was a little lower (22% in Tigray, 27% each for Amhara and Oromia, and 18% in SNNPR). These figures are significantly higher if we look at urban areas alone: (50% in Tigray, 44% in Oromia, 38% in Amhara, and 32% in SNNPR) [13]. A woman’s ability to control her fertility and the method of contraception she uses are likely to be affected by her self-image and sense of empowerment. A woman who feels that she is unable to control other aspects of her life may be less likely to feel she can make decisions regarding fertility. She may also feel the need to choose methods that are easier to conceal from her husband or partner.Although much of the literature examined socio-demographic, economic and related factors that affect reproductive health outcomes related to contraceptive use in different areas, there is limited research exploring the effect of women’s empowerment which is multidimensional on the use of contraceptive methods in our country, especially in this specific study area. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to explore the determinants of family planning services focusing on women’s empowerment and other related factors among women in Sheka and Bench Maji Zones, South West Ethiopia.

2. Material and Methods

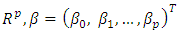

- A community based cross-sectional survey has been be carried out to investigate the effect of women empowerment and other related factors on contraceptive use. The study population consisted of all women age 14 to 49 who were married or living together with a partner and lived in the study area for at least six months earlier to data collection in Sheka and Bench Maji zone at study time.The sample size was calculated using a formula for estimation of a single proportion according to the following assumptions: 28% prevalence of under-five children with acute respiratory infection [14], with 95% confidence interval and 4% marginal of error (d). As a multistage sampling technique was employed to identify study subjects, the default value of deff, the sample design effect, should be set at 2.0 unless there is supporting empirical data from previous or related surveys that suggest a different value [15]. Also 10% was added for non-responses. Thus, the final sample size was 1065.In our study stratification method were applied, urban as stratum one and rural as stratum two. One rule for stratification is that each stratum created should, ideally, be as different as possible. Urban and rural populations are different from each other in many ways (type of employment, source and amount of income, average household size, fertility rates, etc.) while being similar within their respective sub-groups. Therefore, by using simple random sampling method four woredas, Yeki, Sheko, Semen Bench, and Gura Fereda in rural part and two town administrations, Mizan-Aman and She Bench are selected. Even if a proper sampling frame did exist, most of the sample would live in different communities far away from each other, and the time and expense involved in contacting them would be prohibitive. One solution we proposed is to use two-stage sampling as follows:i The population is first divided into clusters (districts), and a list of these first-stage units (or primary sample units) is drawn.ii A random sample of first-stage units (districts) is then selected from this list.iii In each of the selected first-stage units, a sampling frame of the second- stage units (kebeles/ wards) is drawn up, A method of selecting one household to be the starting point and a procedure for selecting succeeding households after that has been applied. One possibility is to choose some central point in a town, such as the market or the central square; choose a random direction from that point count the number of households between the central point and the edge of town in that direction; select one of these houses at random to be the starting point of the survey. The remaining households in the sample should be selected to give a wide-spread coverage of the enumeration area. If the number of women in the selected wards is less than the required sample size, we are shifted to the nearest kebele.Data has been collected using structured questionnaire by administering face to face interviewing of the respondent. In addition to English, the questionnaires was translated into national (Amharic) and local major languages like, Benchigna and Shekigna. Before the start of fieldwork, the questionnaires were pretested in all major local languages to make sure that the questions were clear and could be understood by the respondents. Twenty data collectors are recruited living in the study sub-districts to interview the targeted respondent. They have taken intensive six-days training by the investigators on interviewing techniques, responsibilities, observational, data recording, approaches to communicate with respondents.Independent variablesThe dependent variable contraceptive use was classified into two categories: non-use (coded as 0) and use (users coded as 1) indicating respondents’ use of any method (modern or traditional) of contraception at the time of the survey.Independent variablesIndependent variables included a number of empowerment and gender-related variables. Women’s empowerment was measured on the individual level and along several dimensions as suggested in earlier studies [16].i Economic empowerment: It was assessed using questions related to a woman’s income contribution relative to her husband’s, decisions about how each partner’s income would be used and decisions about major and daily household purchases.ii Socio-cultural empowerment: It could be measured by asking women who decided whether they could visit their family and relatives.iii familial and interpersonal dimensions: who made decisions about health care for the woman, and whether the woman thought she and her partner wanted the same number of childreniv Attitudes about gender roles: attitudes toward wife beating, attitudes toward refusing sex.v Other gender related indicators likely to impact women’s contraceptive was included in the study women’s age at first sex, age at first cohabitation, and ideal number of childrenvi Socio-demographic characteristics which the literature indicates as likely to influence women’s status and their reproductive behavior, including respondent’s age, employment status, level of education, inter spousal education difference and wealth index as controlled variables.Data processing We conduct the analyses in three steps. In the first phase, respondents’ characteristics has been described and the distribution of the dependent and independent variables were explored. Moreover, we can estimate means and prevalence rates of contraception, women‘s empowerment indicators, other gender-related factors, and socio-demographic characteristics.Second, a factor analysis was employed to uncover the underlying structure of the observable data from the survey responses. Since there is no prior theory on the structure of these responses, we assumed that any individual indicator may be associated with any factor. Therefore, the correlation coefficients between the factor and original variable (factor loadings) was used to understand the structure of latent factors in the model. Third, to examine the pathway in our conceptual framework multivariable logistic regression analysis used to examine the determinants of contraceptive use among married women, focusing on the impacts of women’s empowerment. Factor AnalysisThe goal of factor analysis is to reduce “the dimensionality of the original space and to give an interpretation to the new space, spanned by a reduced number of new dimensions which are supposed to underlie the old ones” [17], or to explain the variance in the observed variables in terms of underlying latent factors” [18].The factor analysis model is given by

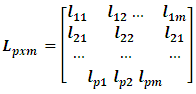

Where Lpxm is a matrix of unknown constants called factor loading

Where Lpxm is a matrix of unknown constants called factor loading

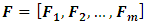

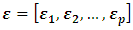

and

and  The coefficient

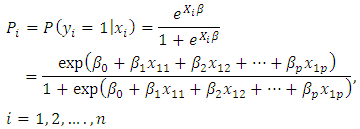

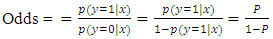

The coefficient  is the loading of the ith variable on the jth factor.Binary Logistic RegressionRegression methods are essential to any data analysis which attempts to describe the relationship between a response variable and any number of predictor variables. Thus logistic regression is used in a wide range of applications leading to binary dependent data analysis [20]. The estimated coefficients tell us the increased or decreased chance of a child having ARI given a set of level of the determinant factors while controlling for the effects of other variables in the model. The likelihood-ratio test was used to check the overall fit of the models and compare both models. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the final model. All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 20.The logistic regression model for explaining data is given by,

is the loading of the ith variable on the jth factor.Binary Logistic RegressionRegression methods are essential to any data analysis which attempts to describe the relationship between a response variable and any number of predictor variables. Thus logistic regression is used in a wide range of applications leading to binary dependent data analysis [20]. The estimated coefficients tell us the increased or decreased chance of a child having ARI given a set of level of the determinant factors while controlling for the effects of other variables in the model. The likelihood-ratio test was used to check the overall fit of the models and compare both models. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the final model. All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 20.The logistic regression model for explaining data is given by, Where,

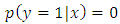

Where,  is the probability of

is the probability of  child having ARIs given child’s characteristics

child having ARIs given child’s characteristics  and

and  is a vector of unknown logistic regression coefficients with dimension of

is a vector of unknown logistic regression coefficients with dimension of  Odds, Log odds and Odds Ratio

Odds, Log odds and Odds Ratio The odds indicates how often something (e.g., y=1) happens relative to how often it does not happen (e.g., y=0), and ranges from 0 when

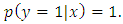

The odds indicates how often something (e.g., y=1) happens relative to how often it does not happen (e.g., y=0), and ranges from 0 when  to

to  when

when  the log of the odds known as the logit ranges from

the log of the odds known as the logit ranges from

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Result of Descriptive Statistics

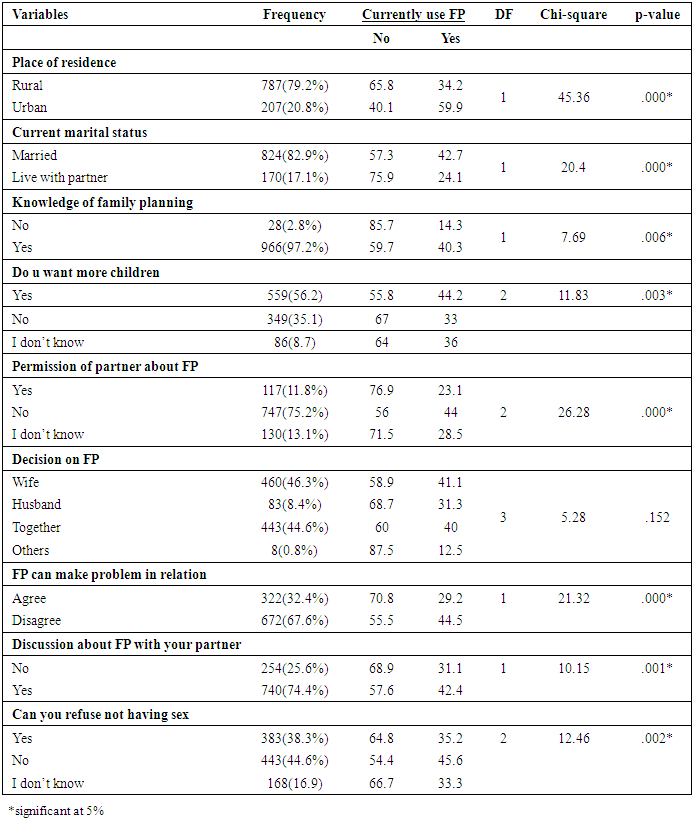

- A total of 994 currently married women or live with partner in reproductive age group were included in the study. The initial population consisted of 1065 women. Out of this 994 (93.3%) currently married women or live with partner in childbearing age group were selected and studied in the analysis and others were excluded due to incompleteness and inconsistency of data on the variables which are considered as important for the analysis.From the sampled women, about 39.5% of the women were using contraceptive with high prevalence among married women (42.7%) and 24.1% couple live with partner in Sheka and Bench Maji Zone, South west Ethiopia. The result of table 1 reveals that 79.2% of women comes from urban rural area with lower prevalence of contraceptive use (34.2%) as compared to women’s comes from rural area with 59.9% of them use contraceptive.

|

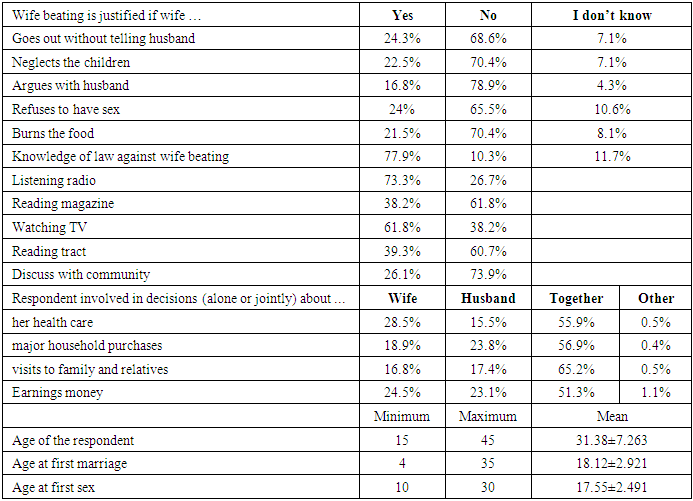

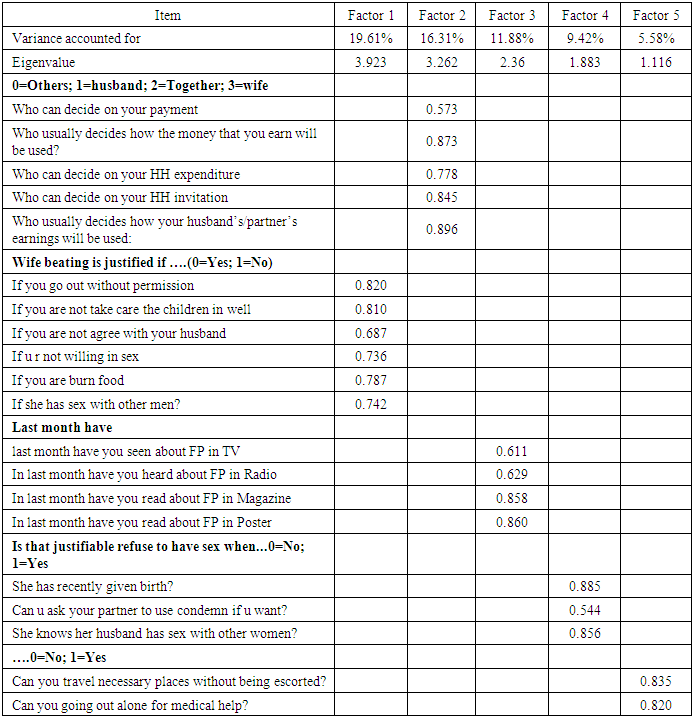

3.2. Result of Factor Analysis

- Five factors measuring women empowerment were extracted using varimax rotation from the twenty variables in the factor analysis and these factors accounted for 62.7% of total variance explained. The majority of the variables used in the factor analysis have high loadings (in most cases greater than 0.7), confirming that the rotated factors reasonably represent the original variables. The component matrix and factor loadings are presented in table 3. We obtained factor scores for each respondent on the four factors extracted from the fifteen variables and these were used as the key independent variables in the final multivariate model. We named the four factors representing women’s empowerment indicators as follows:

|

|

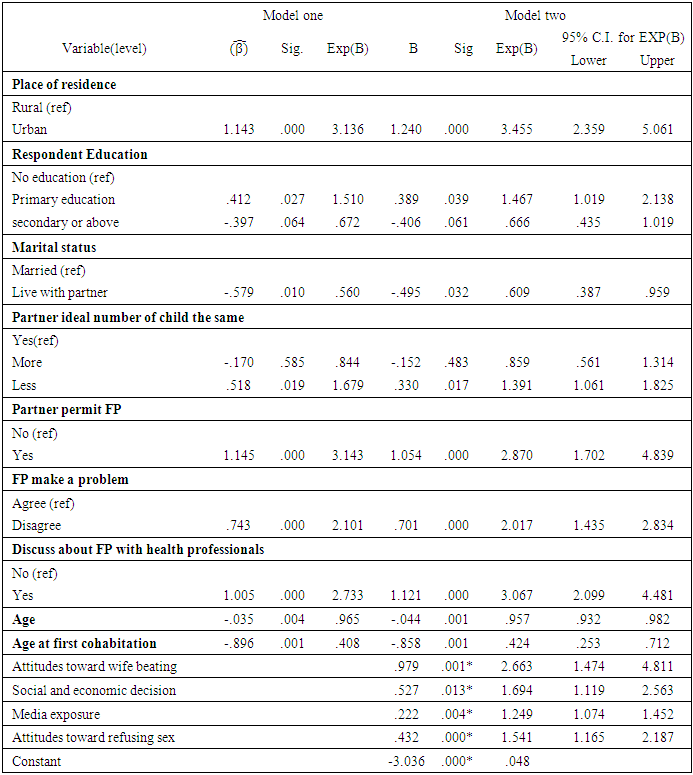

3.3. Results of Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis

- Two models were fitted to examine the effects of women’s empowerment on contraceptive use. Table 4 presents the estimates, adjusted odds ratios, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) of the two models. In the first model, socio-economic and gender-related indicators were entered and in the second model, these control measures were entered with women’s empowerment factor scores to assess their net effect on women’s use of contraception.

|

3.4. Discussions of the Result

- Women’s empowerment is a complex concept that is often difficult to operationalize. Most studies of women’s empowerment and family planning so far have only examined a single or a few aspects of empowerment. The current study measures the multiple dimensions of empowerment and used a factor analysis to outline these dimensions, and explores the associations between different dimensions of women’s empowerment and contraceptive practice based on the data collected from August 10-20, 2016 on Sheka and Bench Maji zone, south west Ethiopia. The result which obtained discussed as follows: The descriptive analysis of the study revealed that 39.5% of the women reported currently used any contraceptive method. Which is higher than the EDHS result for Ethiopia (29%).The results displayed in Table 4 show that the likelihood of using contraceptive was significantly associated with place of residence. Women’s who living in urban were 3.455 times more likely use contraceptive than in rural. This result is in line with study conducted in Ethiopia and Sub-Saharan countries [20, 21].The result of ordinal logistic regression analysis shown in Table 3 describes that mother education level was positively associated with uptake of family planning services for those with a primary-level of education compared to those with no education. This finding is similar to previous reports from experience in developing countries and Results from five Asian countries [22, 23]. This may be More educated women tend to have the knowledge and are motivated to use reproductive health services.Similarly variable representing the difference between a husband/partner‘s ideal number of children and his wife‘s ideal number was significant. When a husband‘s ideal number of children was larger than his wife‘s, she was 44% less likely to use contraceptive than both have equal ideal number of children. This result is similar with study done in Tanzania [24]. This may due to that men who subscribe strongly to such beliefs have increased sexual decision making power and are more likely to be perpetrators of violence.This study also indicated that those women whose husband’s approve using contraceptives were almost three times more likely to use contraceptives. This is in line with the previous studies in Pakistan and Ethiopia [25, 26, 27]. This implies that male involvement has an important role on the use of contraceptives.The study revealed that most dimension of women’s empowerment factors were significantly associated with use of contraceptives. Hence, dimensions of women’s empowerment representing women independent socio-economic decision making, attitudes toward refusing sex, attitude towards domestic violence and women’s media exposure had a positive association with contraceptive use. These findings were consistent with the previous studies conducted in Rural Kenya, Nepal and Eritrea [28, 29, 2]. Table 4 model two, when all dimensions of empowerment were included in the model, the results show that the use of contraception is dependent on the women’s household socio-economic decision, women’s attitude towards domestic violence, media exposure and women’s attitudes toward refusing sex. The higher the score of empowerment in each of these dimension, the higher the likelihood that a woman would report using contraception.From dimensions of empowerment women attitude towards physical mobility was not significantly associated with current contraceptive use of women in this particular study area. In other word, contraceptive use behaviors of women do not depend on whether women can make decisions about visit families and friends [30]. This finding was congruent with a study done in Egypt by [31].

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- In conclusion, this study points out important associations between several dimensions of women’s empowerment and contraceptive use. From multiple logistic regressions living in urban area, being literate, partner/husband approve family planning, discuss with health profession about family planning and disagreement on contraceptive can make problem shows positive effect on current status of women using contraceptive. In contrary women living with partner/ not married, current and age at first cohabitation showed that negative effect on women currently using contraceptive.Finally, the effect of women empowerment extracted from factor analysis; attitudes toward refusing sex, attitudes toward wife beating, and socio- economic decision in household found to be most significant predictors for current status of women using contraceptive. Hence, we conclude that women’s empowerment is an important determinant of contraceptive use in this particular study area. The above findings are expected to update knowledge of reproductive empowerment of women and help policy planners to develop strategic plans. The concerned body should give attention on adoption of family planning services for couples who are living in rural areas of south west Ethiopia. Moreover, encouraging communication between couples and involving men more in family planning are key, while most couples agree on reproductive matters, husbands who oppose contraception or worry about its side effects often prevent their wives from using it.The family planning program should strengthen its efforts to encourage husbands to support women’s economic and social autonomy. Because improving gender equity in the family will help women to be responsible stewards of their family’ resources. Finally the finding implies that women’s empowerment must be integrated into family planning programming in this particular study area. Since as the women empower either in economic or health matter they will better use contraceptive. Further research is needed to identify the extent of male involvement in family planning in this particular study area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to express my special gratitude to all manager of women and children affaires officers of the two zones for their important directions, preparing the available data, encouragement and support from the initial to final level during this study. Moreover my special thanks have goes to Mizan -Tepi University, especially Institute of Research and Community Development Support office for providing me a chance for completing this community based research and financial support. Finally I would like tanks to academic staff members in department of Statistics especially Mrs. Yewulshet M, for helping me in developing the research by giving unreserved comment and suggestion.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML