-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2018; 8(3): 53-59

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20180803.01

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Theoretical Knowledge Retention of Some Nigerian Teachers 15 Months after Initial Training

Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso1, Chukwudi Ochi Onyeaso2

1Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt / University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

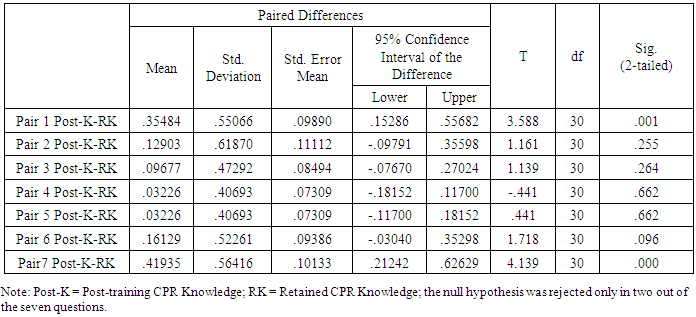

Introduction: For effective bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to be achievable, potential bystander CPR providers must be able to retain sufficient CPR knowledge for a reasonable time frame after training. This study aimed at ascertaining the retained CPR theoretical knowledge of some Nigerian teachers after 15 months of CPR training. Materials and Methods: A quasi-experimental study design was used. From the initial cohort of forty one (41) teachers, thirty one (31) of them participated in the last phase of the study. The same self-administered questionnaire with seven (7) questions on their theoretical CPR knowledge, used initially immediately after their CPR training in 2016 to assess them was used again in December 2017 without further training. The data was analysed using both descriptive and paired samples t-test statistics. Results: Generally, the participants had good retention of the CPR theoretical knowledge that were not statistically significantly different from their post-training knowledge earlier (P > 0.05) except in two questions where the differences (CPR knowledge losses) were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Conclusions/ Recommendations: The Nigerian teachers retained satisfactory CPR theoretical knowledge after 15 months of initial training, which holds promise for their ability to provide bystander CPR for victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCAs) and the training of their students with the possible incorporation of CPR programme into Nigerian schools’ curricula. There is need to repeat the study with larger sample sizes.

Keywords: CPR theoretical knowledge, Retention, Teachers, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Adedamola Olutoyin Onyeaso, Chukwudi Ochi Onyeaso, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Theoretical Knowledge Retention of Some Nigerian Teachers 15 Months after Initial Training, Public Health Research, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2018, pp. 53-59. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20180803.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The important place of teachers in achieving effective bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in different nations of the world has been documented [1-5]. It is not enough to expose potential bystander CPR providers such as teachers to the teaching and training in CPR but their ability to retain such information for some time before they are re-trained is central for any effective bystander CPR provision [6].Even medically trained professionals require re-training for effectiveness. Hammond et al [7] reported that nurses retained virtually equivalent level of theoretical knowledge of CPR 18 months after advanced life support training unlike their skills which dropped markedly. It is known that one of the major hindrances to laypersons performing bystander CPR when needed is lack of confidence often based on poor knowledge of what is expected of them [1, 8-12]. According to Mpotos et al [1], 61% of the teachers interviewed felt incapable and unwilling to teach CPR because of their perceived lack of knowledge to do so despite their previous exposure to CPR teaching while 73% wished they had more training in CPR. In all, only a small proportion of the teachers they assessed felt competent to handle CPR teaching for their students. Unlike other countries, Nigerian Government is yet to make any significant effort toward encouraging bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation for lay persons. Meanwhile, it is known that the public health burden of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is not limited to developed economies of the world but has been reported among the less socio-economically advanced countries [13-20]. To the best of the knowledge of the authors, there is no reported Nigerian study on retention of the theoretical CPR knowledge of teachers after training which is key in their ability to provide bystander CPR for victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCAs). The only related Nigerian study recently published was on the retention of CPR skills among some Nigerian secondary school children that reported significant loss of CPR skills by the participants over a 6-month timeframe [21].In furtherance of our advocacy for the needed attention to bystander CPR in our communities in Nigeria through the involvement of teachers and secondary school students, the present study aimed at assessing the retained CPR knowledge of a group of Nigerian teachers over a 15-month timeframe. It was hypothesized that the retained CPR knowledge of the teachers would not be statistically significantly lower than their post-training CPR knowledge 15 months earlier.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

- This study was carried out using a quasi-experimental cohort design.

2.2. Population of the Study

- As previously reported [22], a cohort of forty one (41) Nigerian teachers who came for their Sandwich Programme in the Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education of the Faculty of Education at the University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria were taught and trained in the conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The participants came from different public and primary and secondary school in Nigeria involving the following three (3) Geo-Political Regions: South-South Region having six states – Edo, Delta, Bayelsa, Rivers, Akwa-Ibom and Cross River; South-East Region with five states – Abia, Enugu, Anambra, Ebonyi and Imo; and North-Central Region with six states plus the Federal Capital Territory (FCT)- Kogi, Benue, Kwara, Niger, Nasarawa and Plateau. The CPR knowledge of the same participants was re-assessed in December, 2017 (15 months after their initial teaching and assessment in September 2016). The original research plan was to re-assess their retention of CPR knowledge a year after the initial training but it was disrupted by a nation-wide industrial action by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) in Nigeria as the participants could not return for their studies as scheduled. However, the participants returned 15 months after the initial assessment and were then re-assessed.At the time of the re-assessment of the CPR knowledge of the cohort, only thirty one (31) of them were present and participated in this phase of the study. No further teaching on cardiopulmonary resuscitation was given to the cohort before the re-assessment. As was done in 2016, the same investigator (Assessor) distributed to the 31 participants the same questionnaire containing the same questions which they answered post-teaching on CPR 15 months earlier (see Appendix).Determination of Poor and Good CPR Skills RetentionFor each of the seven questions on CPR knowledge, retention of at least 50% of the post-training CPR knowledge is considered acceptable and any score less than that is considered as poor CPR knowledge retention.

2.3. Null Hypothesis

- It was hypothesized that the retained CPR knowledge of the teachers would not be statistically significantly lower than their post-training CPR knowledge 15 months earlier.

2.4. Data Analysis

- In addition to descriptive statistics, the data collated immediately after training 15 months ago and the present CPR knowledge of the final cohort were analyzed using the paired samples T-test at P < 0.05 level of significance.

3. Results

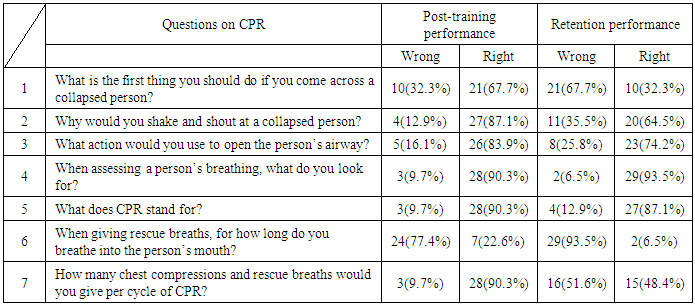

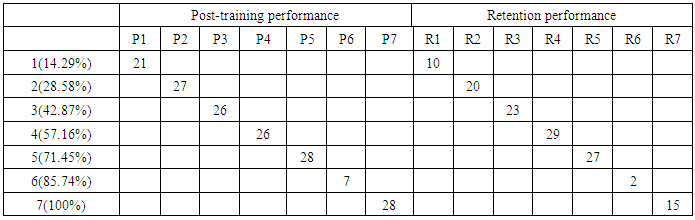

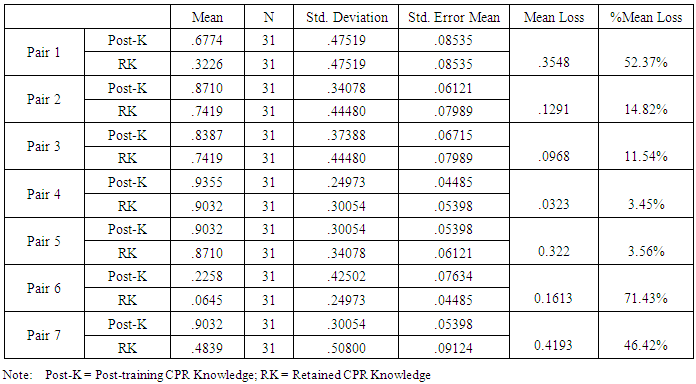

- Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the responses of the participants to the questions on CPR knowledge 15 months earlier after the teaching and their last responses (retained CPR theoretical knowledge) in December 2017. The Table shows that their worst CPR theoretical knowledge was found in 6th question (when giving rescue breaths, for how long do you breath into the person’s mouth?) with only 6.5% correct responses while the best response was on question 4 (when assessing a person’s breathing, what do you look for?) having 93.5%.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- This first Nigerian quasi-experimental cohort study on theoretical knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation has shown generally good retention of the theoretical knowledge of CPR by the Nigerian teachers with statistically significant differences found only in two questions between their earlier post-training knowledge and their retained knowledge after 15 months. This finding is considered encouraging based on the fact that all the participants only had the first opportunity to learn about CPR when they were taught during the initial period of this study in September 2016.Retention of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge and skills have been a challenge which has necessitated the periodic re-training adopted worldwide [6, 7, 23-26]. Mpotos et al [1] reported that despite having about 59% of their respondents with previous CPR training, 61% of the teachers felt incapable and not willing to teach CPR, and mainly because of a perceived lack of knowledge of CPR in 50%. In addition, 69% of the respondents felt incompetent to perform correct cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) while 73% of them desired more training in CPR. According Nishimaya et al [26], in-service and pre-service nursing professionals were assessed immediately after exposing them to paediatric CPR training and 6 weeks later. It was discovered during the reassessment 6 weeks later that though both improved in CPR knowledge and skills, the in-service nurses did retain CPR knowledge better with time than skills. It is known that effective bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation can double or triple the chances of survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) cases [27]. However, this can only be achievable in bystander CPR if the fears of these non-medically qualified bystanders are overcome through proper teaching and training. One of the major fears of potential bystander CPR providers is fear of contacting infections in course of giving rescue breaths to victims of OHCA [27]. In our present Nigerian study, the question on providing mouth-to-mouth breaths to victims had the lowest percentage in terms of the participants remembering it. The same pattern is seen even in their post-training responses 15 months ago. This could be a reflection of the attitude of the participants to this aspect of bystander CPR provision. In fact, two related earlier Nigerian reports indicated the unfavourable attitudes of both secondary students and teachers to mouth-to-mouth respiration [28, 29].These suggest the need to introduce compression-only bystander CPR in further Nigerian research efforts in this direction. According to Nishiyama et al [30], the shortened chest compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation mass training programme appeared to help members of the general public retain cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills better than the conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation training programme.It is important to note that the two questions where there were significant differences between their earlier CPR knowledge and their retained knowledge in our study have to do with: what is the first thing you should do if you come across a collapsed person? and how many chest compressions and rescue breaths would you give per cycle of CPR? These findings would need to be addressed in future CPR trainings in Nigeria because it means that the participants forgot these aspects of the training much faster than the rest. Competency in CPR has been defined as the ability to acquire and retain CPR cognitive knowledge and skills in order to provide CPR in cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) situations [31-33].Strengths and Limitations of this StudyThis study has the strength of having a fairly representative sample as the participants were drawn from different schools from various parts of the country, as well as being the first quasi-experimental study from Nigeria involving teachers who are very important stakeholders in developing bystander CPR programme in schools. However, it has been limited by the relatively small sample size occasioned by natural attrition as ten participants who originally were part of the initial cohort could not come back for the retention phase of the study. Therefore, the general extrapolation of the results of this study should be done with care. This call for more related studies in Nigeria involving bigger sample sizes.

5. Conclusions

- The Nigerian teachers retained satisfactory CPR theoretical knowledge after 15 months of initial training, which holds promise for their ability to provide bystander CPR for victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCAs) and the training of their students with the possible incorporation of CPR programme into Nigerian schools’ curricula.

6. Recommendations

- 1. There is need for more similar studies with larger sample sizes that possibly could involve more teachers from more schools in the North East and North West geo-political regions of Nigeria, although it will have more financial implications.2. There is need to carry out some similar studies in Nigeria using the chest compression-only training so as to compare such with the conventional training results.

Appendix

- QUESTIONNAIRE ON CPRSection A: Personal DataPlease tick as it applies to you.1. Gender: Male:

Female:

Female:  2 Age in Years: ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3. Official status at workplace -------------------------------------------------------------------------4. Name of workplace: --------------------------------------------------------------------------------5. For how long have you been teaching? ------------------------------------------------------------6. In which state is your work place? ----------------------------------------------------------------7. As a sandwich student, please state your Department here in Uniport ------------------------Section BConcerning a collapsed victim, please tick only one option in questions below.5. What is the first thing you should do if you come across a collapsed person?Call an ambulanceTry to get the person to respond to youCheck to see if the person is breathing normally6. Why would you shake and shout at a collapsed person?To open the airwayTo restart the heartTo check for response7. What action would you use to open the person’s airway?Tilt the head back and lift the chinTilt the head and push the chin downTilt the head down and turn the chin to the right8. When assessing a person’s breathing, what do you look for?Chest movementMovement of the eyesMovement of nose9. What does CPR stand for?Call Respond ReactCardiopulmonary ResuscitationCitizen Please Respond10. When giving rescue breaths, for how long do you breathe into the person’s mouth?1 second5 seconds10 seconds11. How many chest compressions and rescue breaths would you give per cycle of CPR?20 presses and one breath30 presses and two breaths30 presses and three breaths

2 Age in Years: ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3. Official status at workplace -------------------------------------------------------------------------4. Name of workplace: --------------------------------------------------------------------------------5. For how long have you been teaching? ------------------------------------------------------------6. In which state is your work place? ----------------------------------------------------------------7. As a sandwich student, please state your Department here in Uniport ------------------------Section BConcerning a collapsed victim, please tick only one option in questions below.5. What is the first thing you should do if you come across a collapsed person?Call an ambulanceTry to get the person to respond to youCheck to see if the person is breathing normally6. Why would you shake and shout at a collapsed person?To open the airwayTo restart the heartTo check for response7. What action would you use to open the person’s airway?Tilt the head back and lift the chinTilt the head and push the chin downTilt the head down and turn the chin to the right8. When assessing a person’s breathing, what do you look for?Chest movementMovement of the eyesMovement of nose9. What does CPR stand for?Call Respond ReactCardiopulmonary ResuscitationCitizen Please Respond10. When giving rescue breaths, for how long do you breathe into the person’s mouth?1 second5 seconds10 seconds11. How many chest compressions and rescue breaths would you give per cycle of CPR?20 presses and one breath30 presses and two breaths30 presses and three breaths Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML