-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2018; 8(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20180801.01

Role of Monetary Incentives on Motivation and Retention of Community Health Workers: An Experience in a Kenyan Community

Mbugua Gathoni Ruth1, Oyore J. P.2, Mwitari James3

1Department of Community Health Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Mount Kenya University, Thika, Kenya

2Department of Community Health, School of Public Health, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

3Department of Research, Ministry of Health, Kenya

Correspondence to: Mbugua Gathoni Ruth, Department of Community Health Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Mount Kenya University, Thika, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Objective: The aim of the study was to assess the role of monetary incentives on motivation and retention of Community Health Workers in Kibwezi Sub-county. Methods: It was a cross-sectional comparative study in which retention of community health workers receiving monetary incentives and those not receiving monetary incentives was compared. Data was collected using a structured questionnaire, key informant interview guide and focus group discussion guide. Relationships between variables were determined using logistics regression Results: Monetary incentives were cited as the main motivator with majority of the CHWs reporting a salary as the factor that would motivate them the most. There was higher attrition rates (13%) among those not receiving any form of monetary incentives compared to those receiving monetary incentives (4%). There was a statistical significant difference in attrition rate between CHW’s receiving monetary incentives and those not receiving monetary incentives. 80% of CHWs not receiving monetary incentives had ever contemplated dropping out of their CHW roles compared to 66% among CHWs receiving monetary incentives. The main reasons cited for attrition of CHWs included financial constraints and inadequate compensation for work done. Conclusion: The study findings show that provision of monetary incentives has an influence on the attrition of CHWs. The attrition rates were higher for CHWs not receiving monetary incentives compared to CHWs receiving monetary incentives. Financial incentives are the most reported incentives to enhance the retention of CHWs. Provision of monetary incentives to CHWs should be explored to enhance their retention.

Keywords: Community Health Worker, Retention, Monetary incentives

Cite this paper: Mbugua Gathoni Ruth, Oyore J. P., Mwitari James, Role of Monetary Incentives on Motivation and Retention of Community Health Workers: An Experience in a Kenyan Community, Public Health Research, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20180801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Globally health workers shortage is an emerging problem especially in developing countries. This is worrisome as the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 3 is dependent on the accessibility of adequate, affordable and quality health services to the communities. In response to the shortage of skilled health care workers, Community Health Workers have been trained across countries to deliver services in underserved communities. CHWs who were trained to provide care in 1980s in line with the Alma Atta Declaration are still providing care in communities they reside in up to date. [1]In Kenya like other countries CHW programmes have been established by the Ministry of Health and Non- Governmental Organizations across the country. The main aim of the community strategy which was outlined in the second National health Sector Strategic Plan was to empower communities to take responsibility of their own health. The Community Owned Resource Persons responsible for this were the CHWs who would be trained to serve their communities. The Kibwezi Rural Health Scheme (KRHS) was established by AMREF in partnership with the Ministry of Health in 1978 as a community project in a geographically underserved population with inadequate health facilities. The main aim of the project was to improve health coverage in the area using cost effective strategies. [2]The definition and remuneration of CHWs varies across countries. In Brazil, CHWs were integrated into the civil service in 1991 and receive a salary and are recognized as professionals since the year 2002. In Malawi CHWs are employees of the Ministry of Health and receive a monthly salary and remuneration like other health care providers. [3] In Ethiopia’s Gumer District, money was contributed by households and used to support CHWs in the form of a stipend. This led to the reduction of the attrition rate from 85% a year to 0%. [4] In Nigeria, Village Health Workers (VHWs) worked on part time and received a stipend ranging from US$13 to $27 a month. Poor pay was often cited as the reason that the VHWs found difficulty in carrying out their work. [5] In Kenya CHWs trained by the Ministry of Health work as part time volunteer workers. However CHWs trained by other partners have been receiving monetary incentives. [6]Community Health Worker programmes have been facing a lot of challenges since their inception. The retention of the trained CHWs has been a major problem in the implementation of the programme across countries. Much has been debated regarding whether CHWs should be paid or volunteers without resolution. Many programmes have recommended volunteers as being ideal but the back drop has been high attrition rates. Generally review of the CHW programmes with volunteers have reported higher rates of attrition. High attrition rates reported across countries vary between 3%- 77%. [7] A review carried out across countries reported 30% and 50% attrition rates in Senegal and Nigeria respectively. [1] CHWs in Solomon Islands attributed their dropping out to poor remuneration and lack of support from their families while others had used the position as stepping stone to becoming a qualified nurse. [8] Similarly CHWs in Bangladesh’s became inactive due to lack of family approval and inadequate remuneration. The loss experienced from the dropping out of a CHW was approximately 24 dollars. [9] High turn-over among CHWs is attributed to a number of factors with the most common being poor remuneration and selection of CHWs. [10]The retention of CHWs ensures that there is continuity of their work in the community and ensures the resources used for training are utilized adequately. The dropping out of CHWs leads to the loss of resources and the experience gained by CHWs and households are left unattended before replacement for the CHWs are done. [7] The retention of CHWs has been neglected despite being a very vital process indicator in the implementation of the programme and many questions remain unanswered as there is paucity of data. This is despite task shifting being a main focus in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. [11] The motivation of CHWs and in turn their retention is very important as motivation and high retention rates impacts on the sustainability and cost effectiveness of the CHW program, and hence the aim of the study was to assess the role of monetary incentives on motivation and retention of CHWs.

2. Materials and Methods

- The study was undertaken in Kibwezi Sub-county, Makueni county, Kenya. Kibwezi subcounty is one of the geographically underserved regions in Kenya. The Community Units receiving monetary incentives included in the study were: Mukaange, Nthongoni, Ngulu and Ivingoni and those from Community Units not receiving incentives were Mtito andei, Athi-kamunyuni, Nzambani and Athikiaoni. The study design was a Cross-Sectional Comparative study which involved the selection of Community Health Workers in Community Units receiving monetary incentives and a comparative group not receiving monetary incentives in Kibwezi Sub-county. Both quantitative data and qualitative data were collected.Multi stage sampling was used to select CUs receiving monetary incentives and those not receiving monetary incentives within Kibwezi sub-county. Purposive sampling was used to select the CUs and CHWs that have been receiving monetary incentives and simple random sampling was used to select CUs and CHWs that are not receiving monetary incentives. 140 CHWs receiving monetary incentives and 142 CHWs not receiving monetary incentives were selected to participate in the study making a total sample size of 282.A Structured questionnaire was designed, piloted and used to collect quantitative data from the CHWs in the selected CUs in Kibwezi, the study area. A total of 282 CHWs from the sample population were interviewed. A total of 15 Key Informant Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured tool for key people involved in the implementation of Community Strategy in Kibwezi Sub-county. These included; DHMT members (District Public Health Officer, District Public Health Nurse), Community Strategy Focal Point Person, Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs). A total of 6 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were held comprising of members of Community Health Committee. Secondary data was collected through the review of health records from the link health facilities of the CUs. The attrition of CHWs in the selected CUs was assessed through the review of the CHEWs registers and Community Health Information System (CHIS) Records. The current active CHWs were assessed on their intention of dropping out of the programme.The Quantitative data was analysed using the Stata Version 11. The association between the variables was analyzed using multiple logistics regression and these regression models were used to predict the adjusted odds ratio (ORs) at 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant in the study. Qualitative data was entered and analyzed based on key themes of the study.Ethical clearance was sought from Kenyatta University and permission to carry out the study was sought from National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI). Participant’s autonomy and privacy was observed during the process of data collection.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics

- There was a significant difference in the gender composition of CHWs receiving monetary incentives and those not receiving monetary incentives. 64.6% of the male CHWs constituted the group receiving monetary incentives compared to 35.4% among the group not receiving monetary incentives. Majority of CHWs from both groups were aged 30-49 Years. There was no significant difference in the age between the two groups. Majority of the CHWs were married for both groups. Majority of CHWs from both groups had attained secondary and primary education with majority for both groups being farmers.

3.2. Role of Monetary Incentives on Motivation and Retention of CHWs

- All CHWs trained by the Government of Kenya through the Ministry of Health were volunteers. All CHWs trained by other training partners which included USAID APHIAII and APHIA Plus were all receiving monetary incentives whereas those trained by AMREF had some CUs receiving monetary incentives whereas others did not. CHWS not receiving monetary incentives were more likely to report an intention of dropping out. [OR =2.469136 P value = 0.008 (CI 95% 1.269603, 4.801998)]. The discrepancies in the payment of CHWs were reported during the Focus Group Discussion. A CHW in a CU not receiving monetary incentives reported;“We always wonder why our colleagues are paid and we are not some even mock us and tell us about the money they receive. I really feel demotivated because I work very hard and I’m treated differently”

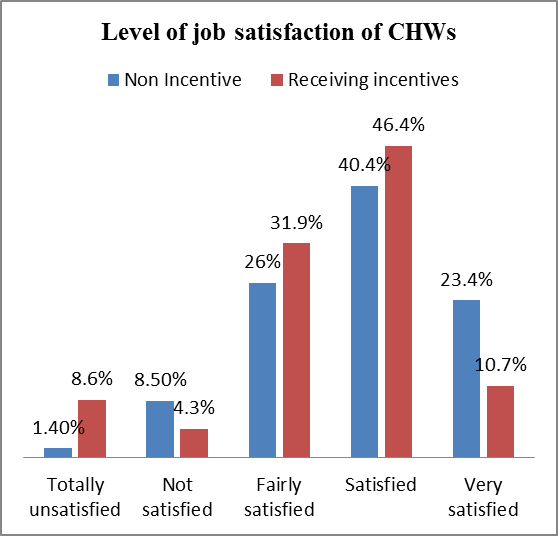

| Figure 1. Level of Job satisfaction by incentive |

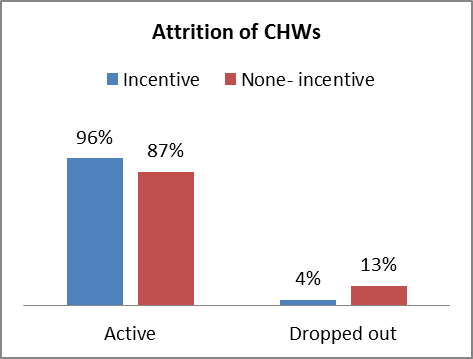

| Figure 2. Attrition of Community Health Workers |

4. Discussion

- It is evident from the study findings that monetary incentives play a key role in the motivation and retention of CHWs. Some CHWs were receiving monetary incentives whereas others were volunteers. This discrepancies in payment can result in demotivation of CHWs who are not paid and may contribute to dropping out. The study findings show that a significant number of the respondents had become CHWs with the hope of getting financial incentives. This would contribute to demotivation of the CHWs if this is not achieved or what is given is not considered adequate. Similar findings 1 were reported in a study done in Busia District, Kenya where 23% of CHWs reported expecting monetary gains during recruitment which led to them dropping out. (12) When asked to rate their job satisfaction as a CHW in relation to their initial expectation, majority reported being satisfied. Monetary incentives were cited as the most motivating factor for CHWs despite them enrolling as volunteers at the beginning and getting satisfaction from serving their communities. This is an indication change in expectations of income as they continue working.The study findings show that CUs not receiving monetary incentives had higher attrition rates of CHWs than CUs receiving monetary incentives. This could be attributed to the CHWs who do not receive monetary incentives having a low morale due to inadequate compensation for the work done which may lead to them dropping out of their CHW roles. This could also be attributed to the CHWs getting demotivated as others are paid whereas they are not paid yet they perform similar roles. This could be also be attributed to CHWs who are receiving monetary incentives feeling that the compensation is an indication of being acknowledged and approved and assists them to earn a living or supplement other income generating activities and hence their retention. Monetary incentives can increase retention because Community Health Workers are poor people trying to support their families. [7] Similar findings were reported in Kenya, where the dropout rate among CHWs after one year was 30% after 3 years amongst volunteer CHWs. [12] Similar findings were reported in Ethiopia Gumer District, where the introduction of a stipend to CHWs reduced the drop-out rate from 85% to 0%. [4]Majority of CHWs had contemplated dropping out of their CHW roles. This is worrisome as it’s an indication of low morale among the CHWs. The main reasons reported in the study by CHWs that would make one to become inactive or drop out amongst CHWs not receiving incentives were; Financial constraints (54.4%) followed by inadequate compensation (29.82%) compared to those who received monetary incentives where majority (47.3%) cited financial constraints followed by inadequate compensation (24.7%). In Bangladesh, the dropout rate for CHWs was between 31-44% and the reasons cited for attrition were household chores and participation in other socio-economic activities which appeared more profitable. [7] Similar findings were reported in Tanzania where majority of CHWs had the satisfaction of serving their community but inadequate financial remuneration was the most reported challenge while working as a CHW and the reason why majority of them dropped off. [13]Whether CHWs should be paid or not has been debated a lot over the years with majority of the programmes having a preference for volunteers. [1] However the reality is that majority of the CHWs recruited are poor and require income to compensate them for the work done. [14] The study findings indicate that provision of CHWs with monetary support can enhance their retention as evidenced by higher attrition rates amongst CHWs not receiving monetary incentives mainly trained by the GOK. The provision of sustainable performance based financial incentives should be explored to enhance the motivation and retention of CHWs.

5. Conclusions

- Arising from the findings of the study, CHWs remuneration requires to be considered. More emphasis should be given to retention of CHWs in the implementation of CHW programmes. The expectation of income by CHWs should be addressed to enhance their motivation and retention. The remuneration of CHWs with monetary incentives should be harmonized and reorganized to enhance retention of CHWs. Sustainable monetary incentives should be explored to enhance the retention of CHW.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We wish to sincerely thank the Public Health officer and Public Health Nurse in Kibwezi Sub-county Hospital and the Community Health workers for their contribution during the entire process of data collection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML