-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2017; 7(4): 100-105

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20170704.03

Perceived Risk, Willingness for Vaccination and Uptake of Hepatitis B Vaccine among Health Care Workers of a Specialist Hospital in Nigeria

Olorunfemi Akinbode Ogundele1, Funmito Omolola Fehintola2, Adedokun Isaac Adegoke3, Abimbola Olorunsola4, Olorunfemi Sunday Omotosho5, Blessing Odia5

1Department of Community Medicine and Primary Health Care, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo City, Nigeria

2Department of Community Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria

3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, State Specialist Hospital, Ondo City, Nigeria

4Department of Family Medicine, State Specialist Hospital, Ondo City, Nigeria

5Department of Community Health, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex, Ile Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Olorunfemi Akinbode Ogundele, Department of Community Medicine and Primary Health Care, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo City, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

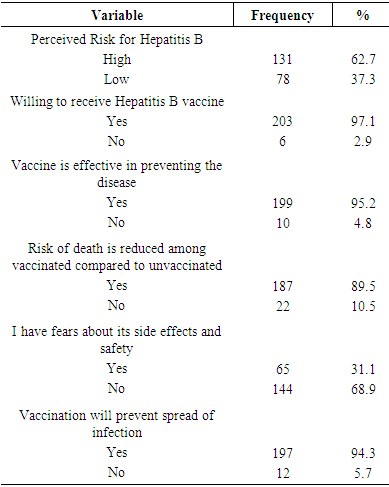

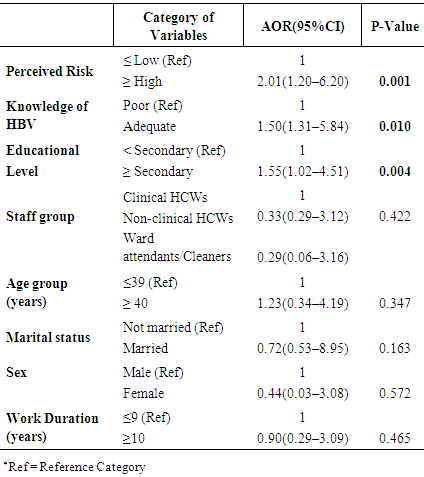

Background: Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of contracting HBV infection from occupational exposure. In spite of this, many HCWs are often not keen on getting vaccinated. Studies have reported the perception of risk among other factors as frequent reasons against Vaccination. The aim of this study was to assess the perceived risk, willingness for vaccination and uptake of hepatitis B vaccine among HCWs of a specialist hospital in Nigeria. Methodology: The study was conducted among 209 HCWs of a specialist hospital, Ondo state, Nigeria. A hospital based cross-sectional design, with structured questionnaire used in data collection. Descriptive statistics were used to identify general characteristics of the sample. Bivariate analysis and binary logistic regression were also performed. Results: About 62.7% of HCWs perceived self to be at high risk of contracting HBV while 37.3% perceived self to be at low risk. Ninety-seven percent of the HCWs were willing to receive the vaccine although 31.1% had fears about the side effects of the vaccine. Knowledge of HBV, educational level, age, and duration of practice were significantly associated with perceived risk. Perceived risk of contracting HBV (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 2.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20-6.20), knowledge of HBV (AOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.31-5.84) and HCWs educational level (AOR 1.55, 95% CI 1.02-4.51) were identified as predictors of willingness for vaccination. Conclusions: Perception of risk for HBV among HCWs was relatively low although willingness for vaccination was high. Intervention to improve perception and correct fears are required.

Keywords: Perception, Risk, Willingness, Vaccination, Hepatitis B, Healthcare workers

Cite this paper: Olorunfemi Akinbode Ogundele, Funmito Omolola Fehintola, Adedokun Isaac Adegoke, Abimbola Olorunsola, Olorunfemi Sunday Omotosho, Blessing Odia, Perceived Risk, Willingness for Vaccination and Uptake of Hepatitis B Vaccine among Health Care Workers of a Specialist Hospital in Nigeria, Public Health Research, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 100-105. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20170704.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Health care workers (HCWs) are at high risk of contracting hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection through exposure to blood, contaminated body fluids, and small sharp instruments. [1, 2] HBV is described as the greatest infectious hazard for HCWs. This description includes the incidence of chronic liver disease due to hepatitis B as well as numbers of deaths resulting from it. Every year, more than 3 million HCWs suffer from percutaneous exposure to blood-borne pathogens. [3] Over 66,000 HCWs are infected by HBV, 500-600 HCWs are hospitalised due to HBV, and out of whom more than 200 HCWs develop chronic hepatitis as a result of occupational exposure. [3-5] HCWs should, therefore, get vaccinated against HBV infection. The vaccine against HBV infection has been available since 1982 and is 95% effective in preventing the infection and its chronic consequences. [6] It is the first vaccine against a major cause of human cancer. [6] HBV vaccination reduces the risk of a person becoming infected with the pathogen as well as transmitting them to another person. The benefit of vaccination in healthcare settings has been shown in many studies [7, 8] as HBV vaccination reduces the risk of a person becoming infected with the pathogen as well as transmitting them to another person. Vaccination is an important infection control measure in a hospital setting. Studies have shown that today’s vaccines are well tolerated [9]. Equally several studies have documented perception of risk and fear of side effect as some of the most frequent reason against vaccination among HCWs. [8]. Perception influence behaviour, an individual perception of risk will impact his decision to get himself protected against the threat of the disease or otherwise. However, perceptions of risk is a subjective assessment of an individual and do not necessarily represent the objective judgment. [10]. When the perceived risk of vaccination is high, an individual is unlikely to get vaccinated; when the perceived risk of infection is high, it is more likely that an individual will subscribe to vaccination. [11, 12] Perceived risk of becoming infected certainly affects HCWs’ vaccination decisions: low perceived risk of infection is amongst the major reasons against vaccination among HCWs [8, 13]. Vaccination rates have been found to be low among HCWs who paradoxically are expected to have a high vaccine coverage rate considering the risk of their occupation. [14] Relatively high knowledge of HBV has been reported among HCWs in Nigeria, in spite of this, attitude vis-a-vis perception of risk is low. [15] This low perception no doubt affects the willingness and eventual vaccine uptake. The gap in risk perception among HCWs in the country calls for concern among all stakeholders seeing that HCWs have a high risk of being infected with HBV. This study aimed to assess the perceived risk, willingness for vaccination and uptake of hepatitis B vaccine among HCWs of a specialist hospital in Nigeria.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Setting

- The study was conducted among HCWs at the State Specialist Hospital (SSH), Ondo City, Ondo State Southwest Nigeria. The hospital serves as a referral facility in the central senatorial district of the state. SSH is a 300-bed capacity hospital with about 420 personnel as at the time of the study.

2.2. Study Design

- A hospital based, descriptive cross-sectional study.

2.3. Study Population, Sampling and Sample Size

- The study recruited 209 HCWs who were aged 18 years and above and were on the staff list of the hospital. This study was conducted as part of a larger study on hepatitis. Recruitment was based on voluntary participation with no random selection. Consecutive enrollment of participants was done until the intended sample size was achieved. Excluded from the study were all trainees, temporary and contract staffs. The sample size was estimated using the Kish Leslie sample size formula for a cross-sectional study. [16] This gave a sample size of 206, however, the study eventually enlisted 209 HCWs who volunteered to participate in the study.

2.4. Data Collection Instrument

- A pretested structured self-administered questionnaire was used in data collection. The questionnaire was used to collect information on socio-demographic data, knowledge of HBV infection, attitude towards risk and vaccination. The questionnaire had seven questions assessing perception towards risk of contracting HBV and their vaccination which was used to compute perceived risk among HCWs. To ensure the validity of the questionnaire, it was reviewed by two experts before pre-test on 20 HCWs in a different health facility from study facility. The questionnaire was adjusted according to the feedback received from the pretest.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Analysis of data was carried out using IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 20. Descriptive statistics was used to describe general characteristics of the sample. Appropriate bivariate analysis such as chi-square was carried out to determine associations between categorical variables. Perceived risk was assessed by assigning scores to each response ‘yes’ or ‘no’ assessing the attitude of the HCWs towards risk for HBV and vaccination. A correct response was scored as one mark while a wrong answer was scored as zero. The scoring range of the question on perception was 0-7. The mean score was calculated and used as cut off. The cut-off for perceived risk was defined as a score above the mean score. Based on perception score, an HCW perceive self to be at high risk if he has a score above the mean score and to be at low risk if he scores below the mean. Knowledge of hepatitis was also assessed in a similar manner as perception, however, using a different set of questions. A score below the mean was considered as poor knowledge whereas a score above the mean was considered as adequate knowledge about hepatitis. Binary logistic regression was used to estimate the association between each covariate such as perceived risk, knowledge and willingness for vaccination with hepatitis B vaccine. A p-value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant in this study.

2.6. Ethical Consideration

- Written informed consent was obtained from each study participants after aims and objectives of the study was explained to them. Ethical clearance was obtained from the research ethics review committee of the hospital.

3. Result

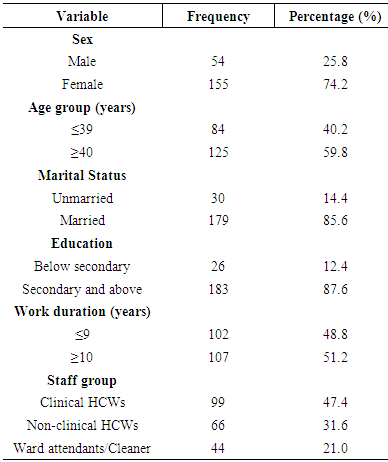

- Two hundred and nine HCWs participated in the study as revealed in Table 1, most of the respondents were female (74.8%). Majority were married (85.6%) with 87.6% having secondary education and above. Slightly more than half of them (51.2%) had worked for ≥10 years in the hospital.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

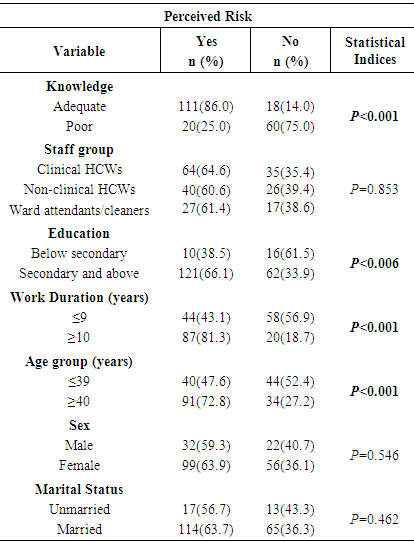

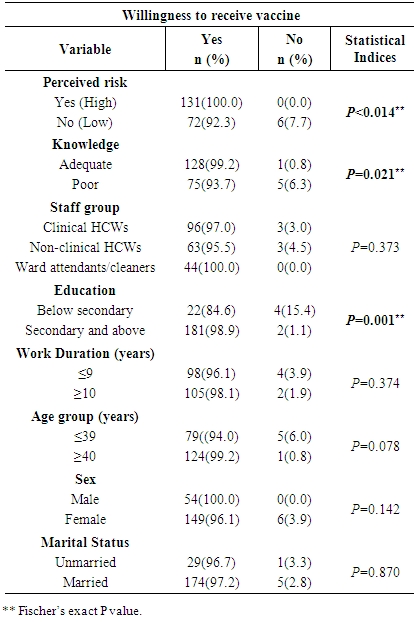

- The benefits of vaccination in health care settings and among HCWs has been shown in numerous studies. While it is attractive to assume that HCWs will likely show a high level of willingness for vaccination uptake and coverage, evidence from literature cautions otherwise. This is because perception of risk among other factors affects HCWs response to vaccination opportunities.In this study, only (62.7%) of the HCWs perceived self to be at high risk of contracting HBV infection leaving out over 37.3% of HCWs with low-risk perception. This proportion (62.7%) was relatively low as it reveals that less than seventy percent of the HCWs in this study perceive self to be at risk. This finding is significant considering the fact that for HCWs, caring for others is their job and patients will expect that HCWs’ motivation to protect them will be at a maximum. [17] The remaining 37.3% approximating to 4 in 10 HCWs that perceive self to be at low risk is of great concern as they are at high risk of contracting HBV and also because risk perception is a significant component of awareness and willingness to protect self. This percentage was, however, lower than the one from the study by Feleke in Ethiopia where the low perceived risk was as high as 63%. [18] The difference in the results observed may be due to methodological difference in definition of perceived risk. The perceived risk of becoming infected indeed affects HCWs’ vaccination decisions: low perceived risk of infection is a factor against vaccination while a high perceived risk favour vaccination. [8, 13] An individual’s perception of risk of infection, lifestyle and attitude towards preventive measures play important role in the utilisation of preventive services and have also been mentioned in regards to uptake of HBV vaccine. These factors also probably serve as a pointer to why educational intervention must be targeted at HCWs as this may result in improvement of perception and attitudes. [19] Amongst individuals and HCWs, aside from the perception of the risk of infection, perception of vaccines’ safety is also an important factor that affects the willingness for and the uptake of vaccination. [20] Thirty-one percent of HCWs in this study had fears about the side effect of the vaccine. It has been documented that fears of side effect are strong in reducing vaccination intentions. A previous study by Betsch et al in Germany showed that fear of side effects significantly reduce vaccination intentions, even when fear of infection was also high. [21] Thus if fears of side effect are low vaccination rate may substantially increase and if fear of side effects increases, vaccination becomes more unlikely.High-risk perception in this study was associated with adequate knowledge of HBV infection, educational level of the HCWs, age of HCWs and duration of practice. Eight in ten of HCWs with adequate knowledge of HBV perceived self to be at high risk for HBV infection, this was significant, considering that adequate knowledge impacts on perception. Six in ten of those with secondary education and above also perceived self to be at high risk of infection. This finding was of note because perceptions of risk are subjective judgments and do not necessarily mirror objective numbers. [22] A higher level of education is likely to create objectivity in the mind of an individual and might explain while HCWs with higher level of education may perceive themselves to be at high risk of contracting infection than those with lower level of education. Another important finding in this study was that in spite of fear of side effect expressed by over 31% of the HCWs, the willingness to receive vaccine was about 97.1%. This is encouraging, though most studies reported poor willingness for vaccination as a result of fear of side effect and safety of vaccine [20]. This finding may not be unconnected with educational programmes on hepatitis received in the facility and in the news media. The willingness to receive HBV vaccine among this group of HCWs was associated with risk perception, adequate knowledge, and education. A high-risk perception increased the odds of HBV uptake and vaccination by 2-fold (2.01, 95% CI=1.20–6.20). A possible explanation for this finding is that when perceived risk of infection is high, it is more likely that HCWs will subscribe to vaccination [11, 12] in keeping with findings from studies in Germany, and Georgia. [17, 23] Despite being a subjective judgment, perception impacts on behaviour and decisions and might as well have impacted on the vaccination decision of this group of HCWs. Adequate knowledge (1.50, 95% CI 1.31-5.84) and obtaining secondary level education and above (1.55, 95% CI 1.02-4.51) also increased the probability of vaccination by 1.5-fold. A probable explanation still is that being educated and having adequate knowledge may generate trust in safety and efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine. Public trust in vaccines has been documented to be very important to public health interventions. [24] Protecting self against risks and threats is a fundamental motivator behind human behaviour and attitudes. HCWs therefore, have a right to be protected against HBV in view of their increased risk and also an obligation to protect others. In view of this, national policies and guidelines promoting and supporting mandatory HBV vaccination for HCWs are necessary. Such regulations should apply to all HCWs as well as those in training. The strength of our study was that it explored extensively perception of risk of infection and willingness for HBV vaccination uptake among HCWs in Nigeria which had not been previously well studied and can be useful for future research and planning. There are, however, some limitations which include the cross-sectional nature of the data, this limits analysing causal relationship between variables. Some HCWs could also have given socially acceptable responses to some questions asked in the questionnaire, this was however minimised by explaining and reassuring about the purpose of the study. In conclusion, we had shown perception of risk for HBV among HCWs as being relatively low although willingness for vaccination was high and was associated with perceived risk, educational level and adequate knowledge of HBV. HCWs’ perception of risk, willingness for uptake of vaccination should be reached through education on risks, correction of fears, as well as interventions highlighting the importance of vaccination.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML