-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2017; 7(4): 85-90

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20170704.01

Association between High Body Mass Index and High Blood Pressure among Adolescents in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria

Oluremi Olayinka Solomon1, Eyitayo Ebenezer Emmanuel1, Olusoji Abidemi Solomon2, Eyitope Oluseyi Amu1, Olukemi Amodu3

1Department of Community Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

2Department of Family Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

3Institute of Child Health, College of Medicine, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Eyitayo Ebenezer Emmanuel, Department of Community Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

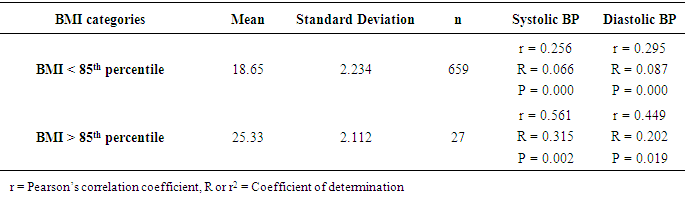

Background: Adolescent overweight/obesity has been shown to be associated with many diseases later in life. This study aimed to determine the association between high body mass index and hypertension among adolescents. Methods: The study was a Cross sectional analytical study. Multistage sampling was used to select 700 adolescents aged 10 to 19 years from four secondary schools in Ado-Ekiti. Validated self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. Anthropometric measurements and blood pressure of respondents were obtained by trained research assistants. Data was analysed using SPSS version 20, Pearson’s correlation and chi square statistics were used to assess association between blood pressure and body mass index. Level of significance was p < 0.05. Result: Prevalence of hypertension among the participants was 6.1%, while about 3.9% had body mass index (BMI) ≥85th percentile for age and sex. About 29.6% of the respondents with BMI ≥ 85th percentile were hypertensive compared to 5.2% among those with lower BMI (p < 0.001). There was a significant positive correlation between BMI and both the systolic and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) with about 31.5% and about 20.2% of the variability in systolic and diastolic blood pressure respectively being explained by BMI alone in those with BMI≥85th percentile (p< 0.05). Conclusion: Adolescents with BMI≥85th percentile for age and sex were more likely to be hypertensive compared to those with lower BMI and BMI predicts both the systolic blood pressure (SBP) and DBP better in those with BMI≥85th percentile for age and sex.

Keywords: Hypertension, Adolescents, Body mass index, Overweight/obesity

Cite this paper: Oluremi Olayinka Solomon, Eyitayo Ebenezer Emmanuel, Olusoji Abidemi Solomon, Eyitope Oluseyi Amu, Olukemi Amodu, Association between High Body Mass Index and High Blood Pressure among Adolescents in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria, Public Health Research, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 85-90. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20170704.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- High blood pressure in children and adolescents is a growing public health problem that is often overlooked by physicians due to the assumption that the adolescents are generally healthier. [1, 2] Similarly, the process of deciding high or normal blood pressure in children and adolescent is not as straight forward as in adults and this probably discourages health workers from routinely checking adolescent blood pressure. [3] Childhood hypertension is predictive of adulthood hypertension so this has important implications for the future health of young individuals in terms of cardiovascular disease. [4] Association between obesity and blood pressure in children and adolescents has been widely reported. [5, 6] A good knowledge of this association is important for understanding, assessing and preventing the public health and medical impact of the anticipated worldwide obesity epidemic which may have an impact on blood pressure in adolescence and in determining future high blood pressure in adulthood. [6] Overweight and obesity among adolescents are now becoming increasingly prevalent in developing countries as a result of an environment characterised by easily available and cheap, energy-dense foods, combined with increasingly sedentary lifestyles such as prolonged time spent watching television, playing video games or using computers. [7-9] Consequently, developing countries are now experiencing a coexistence of under nutrition and over nutrition (termed a double burden of malnutrition) in places where under nutrition was formerly the only cause of concern. [6] Obesity is known to track from childhood to adulthood, and it often begins early in childhood. When this occurs, the chances of an obese child becoming an obese adults are greater than in children of normal body weight. Hence, it is an established fact that obese children and adolescents are more likely to become obese adults. [10] Globally the prevalence of childhood obesity varies, over 30% in USA, 20% in U K and Australia. [11] Previous studies among Nigerian children and adolescents have shown a rise in the prevalence of obesity in Nigeria with the current prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents ranging between 0 to 4%. [9, 12, 13]The increasing prevalence of obesity in childhood and adolescence is a major cause of concern based on the relationship between obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors especially hypertension. It is in the light of this that this study aimed to determine the prevalence of hypertension, obesity and also study the association between overweight and blood pressure among adolescents in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area and Population

- The study was a cross sectional descriptive study carried out in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Ado-Ekiti is the capital of Ekiti State in the South-West region with estimated population of 567,371. The study was carried out among adolescents aged 10 to 19 years in public and private secondary school students in Ado-Ekiti. The schools were selected through a multi-stage sampling technique. In stage-1, two wards were selected out of the thirteen wards through simple random sampling. In stage-2, two secondary schools were randomly selected through a simple random sampling technique by balloting from each of the two wards from the list of schools obtained from the ministry of education, while in stage-3, a class was selected in different arms of the school by simple random sampling and thereafter a proportionate sampling was used to select the number of student in each class using the table of random number. A total of 700 students were selected for the study using the process described above. Students in the selected schools, who are in apparent good state of health were selected for the study, while students whose parents did not consent to the study and those who were absent from school during the period of study were excluded from the study. Approval for the study was obtained from the ministry of education and respective school. Ethical clearance was obtained from University of Ibadan Institution Review Committee.

2.2. Data Collection

- Self-administered questionnaire was used to collect socio-demographic data and anthropometric measurement. The investigators were all adequately trained in all the procedure. Height was measured with subjects standing barefooted using an erect metre rule placed against a perpendicular wall. The subjects stood erect, barefooted heels together against the bottom of the wall with the buttocks, shoulder and head touching the wall and the chin raised. They were told to look straight ahead, take a deep breath, and make themselves as tall as they can. A head piece was then made to rest on the head of the subject and was held firmly to the wall at right angles and the subject was asked to move from under the head piece.Weight was measured using a calibrated bathroom scale. The bathroom scale has been recommended for use in older children and adolescents where the beam scale is not available. Subjects were asked to stand on the weighing scale without shoes and wearing light clothes. They remained upright on the scale with upper limbs to the sides of the body while the weight was read to the nearest 0.1kg and recorded. Each measurement was followed by the adjustment of the scale to the zero mark. A standard 20kg weight was used to confirm the weight on the measuring scale after every 20th subject to ensure precision. Weight and height were used to compute BMI by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters. Students were categorized by age and sex using the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) BMI growth charts as follows: overweight/obese was defined as BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex; while BMI <85th percentile was regarded as normal.Blood pressure was measured with the subject haven been seated for 5 minutes with his or her back supported, feet on the floor and right arm supported cubital fossa at heart level. The right arm was preferred in repeated measures of BP for consistency. The measurement was done with Accoson sphygmomanometer with a cuff that is appropriate to the size of the adolescent’s upper right arm. The stethoscope was placed over the brachial artery pulse, proximal and medial to the cubital fossa and below the bottom edge of the cuff about 2 cm above the cubital fossa. An inflatable cuff bladder, with width that is at least 40% of the arm circumference at a point mid-way between the olecranon and the acromion and length covering 80%–100% of the circumference of the arm.Hypertension is defined as average SBP and/or DBP that is greater than or equal to the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height on at least three separate occasions. Prehypertension in children is defined as average SBP or DBP levels that are greater than or equal to the 90th percentile, but less than the 95th percentile.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- SPSS for Windows software version 20 was used for data analysis. The means and standard deviations (SD) of the BMI, SBP and DBP were calculated and compared using the independent-samples t-test, while categorical variables were compared using the Pearson Chi-squared (χ2) test. Pearson correlation statistics was used to determine correlation coefficients between blood pressure and BMI. Linear regression analysis was used to determine the effects of BMI on the respondents’ systolic and diastolic BP. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

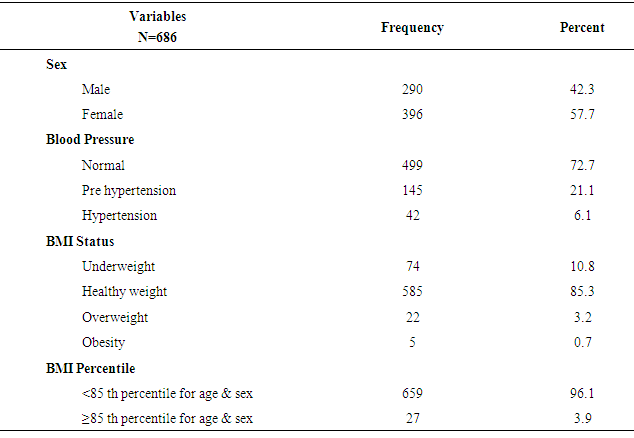

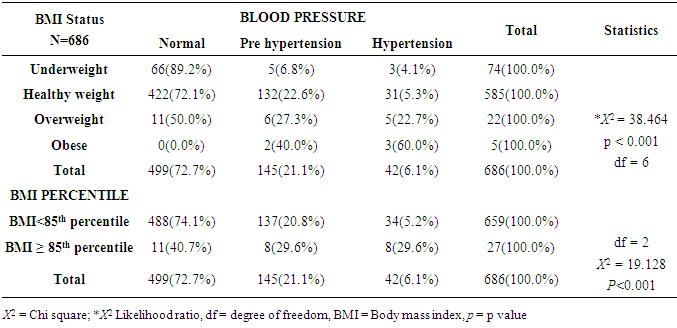

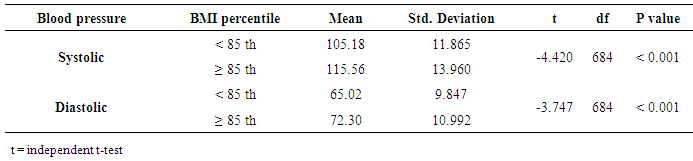

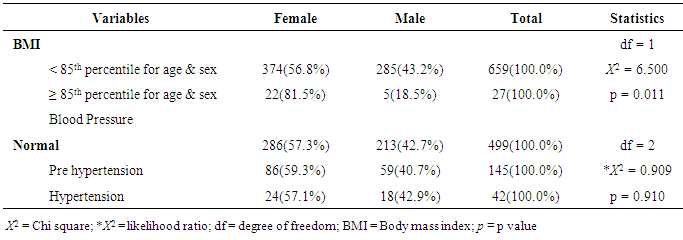

- A total of 686 students completed the study, with 290 (42.3%) and 396 (57.7%) being male and female respectively. The mean age of respondents was 14.2±1.7. Table 1 revealed that about 6.1% of the respondents were hypertensive and about 3.9% of the respondents had BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile for age and sex (3.2% were overweight and 0.7% were obese). About 29.6% of the respondents with BMI greater than or equal to 85th percentile (overweight/obese) were hypertensive compared to only about 5.2% among those with lower BMI (p < 0.001) as shown in table 2.Table 3 revealed that the mean systolic blood pressure was significantly higher in those in with BMI ≥ 85th percentile compared to those with lower BMI (P < 0.001). Similarly, the mean diastolic blood pressure was significantly higher in those with BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex compared to those with lower BMI (P < 0.001).Table 4 revealed that there is a statistically significant association between gender and BMI of respondents. About 81.5% of the female respondents had BMI higher than or equal to the 85th percentile for age and sex compared to the males with only 18.5% (X2 = 6.500, p = 0.011). Table 4 also showed that a greater proportion of the female respondents had pre hypertension and hypertension compared to the male respondents, however, that association was not statistically significant (likelihood ratio = 0.909, p = 0.910).As shown in table 5, among those with BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex, there was a statistically significant strong positive correlation between BMI and both SBP and DBP (r = 0.561 and 0.449 for SBP and DBP respectively). In the same vein, the coefficient of determination R (which is the square of the correlation coefficient and statistically interpreted as the proportion of changes in the SBP and DBP explained by changes in BMI alone) equals 0.315 (31.5%) and 0.202 (20.2%) respectively. Hence, among those with BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex, BMI alone significantly explains about 31.5% and 20.2% of the changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure respectively (p < 0.05). However, similar but weaker correlation was seen among those with BMI lower than the 85th percentile, where BMI only explains about 6.6% and 8.7% of the changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (p < 0.001). Hence, it could be concluded that that the positive correlation existing between BMI and blood pressure is more pronounced in those with higher BMI.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The prevalence of overweight and obesity in this study were 3.2% and 0.7% respectively, this figure is comparable to the prevalence of overweight and obesity reported by Ben-Bassey et al in 2007 of 3.7% and 0.4% respectively among adolescents in Lagos Nigeria, [12] but lower than the prevalence of 6.8% (overweight) and 1.7% (obesity) reported by Ansa et al among Nigerian adolescents. [2] However, this observed prevalence is markedly lower than the prevalence reported among Bolivian adolescents of 14% overweight and 5% obesity. [14] In this study, higher proportion of females than males were either overweight or obese, this is consistent with the findings in majority of the previous studies in this environment, and has been attributed to hormonal changes as a result of puberty which is usually more rapid and more pronounced in females. [12, 15] The observed prevalence of pre hypertension among respondents in this study was 21.1%, this is similar to the prevalence of 22.2% obtained by Ejike et al [5] among adolescents attending public schools in urban and semi urban settlements of Kogi state but higher than that of 7.5% observed by Odey F et al in 2009 [16] in a study among healthy adolescent in Calabar. These group of individuals in the pre-hypertensive and hypertensive categories are those who might become hypertensive later in life if adequate life style modifications such as weight reduction, regular exercise, reduction of alcohol intake and smoking are not instituted thereby increasing the prevalence of hypertension and its attendant complications later in life. [17] The observed prevalence of hypertension in this study showed an increase in the prevalence rate of hypertension among the adolescents when compared with a rate of 3.3% in a study by Akinkugbe et al in Ibadan in 1999, though the rate is higher than that of Ibadan study, it is closer to that of 5.4% observed in Enugu study by Ujunwa et al [17, 18] The difference in prevalence of hypertension in this study compared to that of Akinkugbe et al [19] may be due to methodological differences in the definition of hypertension, while this study utilised the BP percentile for age, sex and height of the adolescents, Akinkugbe et al used a simple cut off 140/90mmHg which likely to underestimate the prevalence of adolescent hypertension. The prevalence of hypertension was also higher in this study compared to 3.7% obtained by Bugaje et al in Zaria (2005). [20] In Bugaje study’s DBP was determined at K4 while it was determined at K5 in this study. However, the observed prevalence rate falls within the documented prevalence rate of adolescent hypertension of 1-13% in Nigerian adolescent. [17]Studies have shown in the last decades that blood pressure in adolescents is rising both in developed and developing countries [21] with attendant possible future increase in cardiovascular diseases especially through the worsening of the risk factors as these adolescents grow into adulthood [22]. This current study has also agreed with many other studies that being overweight is strongly associated with elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure in adolescent. [6, 17, 23]. It has also been clearly demonstrated in this study that the more the BMI of the adolescents the more the tendency to be hypertensive and the converse is also true for those with lower BMI.The implication of these findings is that though usually considered relatively the healthy group in the society, the risk factors for non-communicable diseases such as overweight/obesity and hypertension are becoming prevalent in the adolescent age-group. Hence, simple interventions such as measurement of BMI of children and adolescents could help in early diagnosis of those at risk of cardiovascular disease the leading cause of death globally.

5. Conclusions

- The prevalence of hypertension in this study was high and there is a positive correlation between hypertension and body mass index. Adolescents with BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex were more likely to be hypertensive compared to those with lower BMI and BMI predicts both the systolic and diastolic blood pressure better in those with BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex. Prevention of excessive weight gain in adolescents could be one of the strategies for controlling the rising prevalence of hypertension.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- All staff of Community Health department who participated in data collection and provided technical assistance that culminated into timely conclusion of this work are highly appreciated.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML