-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2017; 7(3): 62-72

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20170703.02

Opening the Door to Funny Turns: A Constructivist Thematic Analysis of Patient Narratives after TIA

Sonia Butler1, Gary Crowfoot1, Debbie Quain2, Andrew Davey2, Parker Magin3, Jane Maguire4

1School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Health and Medicine, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

2School of Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Health and Medicine, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

3Discipline of General Practice, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

4Discipline of Nursing, Faculty of Health, University of Technology, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Correspondence to: Sonia Butler, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Health and Medicine, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

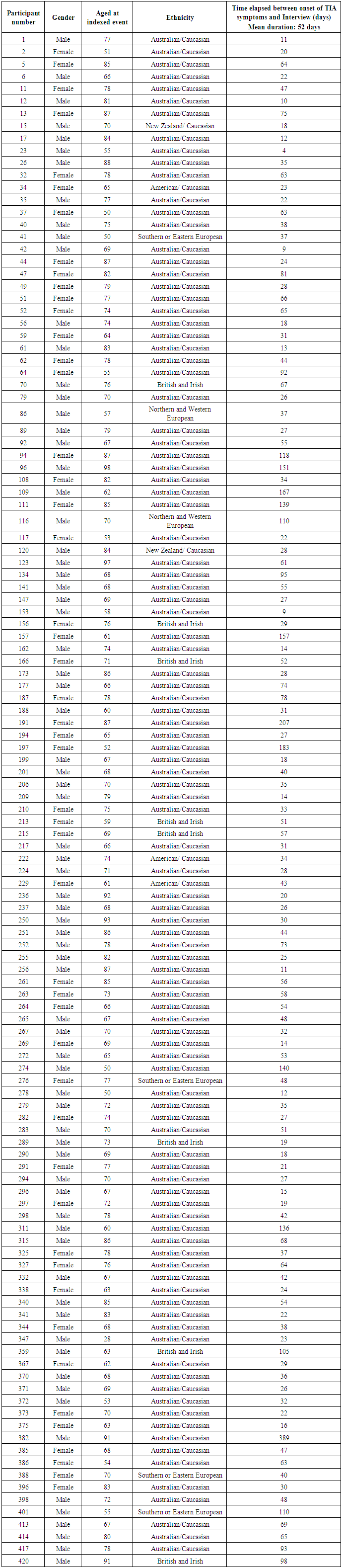

Introduction: It is crucial to enhance timely treatment and secondary prevention following a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and one way to ensure this is to improve the accuracy and promptness of diagnosis. Unfortunately, initiating timely treatment can be difficult due to patients’ lack of knowledge of symptoms and their need for urgency, and difficulties in obtaining this diagnosis. Understanding the TIA event from the patient’s perceptive may open the door to a better understanding of TIA symptomology and improve current difficulties with diagnosis. Method: Narratives of 123 participants, adjudicated to have experienced a TIA, were selected from a TIA/minor stroke cohort assembled by the International Study of Systems of Care in Minor Stroke and TIA [InSiST] study. This National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funded study is currently underway in NSW, Australia. The participants’ TIA experiences were transcribed into narratives, and using constructivist thematic analysis, an insightful description of patient perceptions of, and responses to, their TIA symptoms was obtained. Results: Participants described mental checklists they created in response to their symptoms that reflected the scope of what they knew about TIA/stroke symptoms. Deficits in TIA-specific knowledge were apparent in these lists, which influenced the participants’ responses to their symptoms. Surprisingly, many participants felt they needed to experience all the symptoms on their checklist before they acted. Confusion also arose around additional symptoms, inability to describe symptoms and temporary nature of symptoms, which tended to de-escalate the seriousness of symptoms. These disparities also aided self-attribution of a range of erroneous diagnoses and inhibited appropriate actions. Commonalities in the shared experience of participants also emerged which hindered the participants physical or cognitive capabilities to seek medical treatment. These commonalities included sudden loss of language and bodily control, inability to complete tasks, no awareness of symptoms, or loss of consciousness. This rendered the participants reliant on significant others to gain urgent medical treatment. Conclusion: Health professionals’ identification and acknowledgement of these subjective experiences may add a broader awareness of TIA symptoms at presentation and contribute to more accurate detection or diagnoses of TIA events. The identification of knowledge deficits in people’s utilisation of stroke checklists has implications for both current and future public health stroke campaigns in raising awareness of TIA symptoms. Further studies to explore the subjective experiences of TIA would be beneficial to enhance our understanding of TIA.

Keywords: Transient ischemic attack, TIA, Stroke, Funny turn, Diagnosis, Awareness, Thematic analysis

Cite this paper: Sonia Butler, Gary Crowfoot, Debbie Quain, Andrew Davey, Parker Magin, Jane Maguire, Opening the Door to Funny Turns: A Constructivist Thematic Analysis of Patient Narratives after TIA, Public Health Research, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 62-72. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20170703.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Patients experiencing a transient ischemic attack (TIA) are at high risk of debilitating stroke [1, 2]. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2013 report on Stroke and its Management in Australia states that a TIA must be treated as an “emergency” [3]. This is in response to the incidence of stroke after a TIA being reported as 3.5 - 9.9% at 2 days, 8.0% - 13.4% at 30 days and 9.2% - 17.3% at 90 days [4]. To reduce this risk, urgent medical attention is crucial to ensure prompt assessment and the initiation of effective interventions [5]. The Existing Preventive Strategies for Stroke (EXPRESS) study found that early initiation of treatments led to an 80% relative reduction in stroke risk [6]. Unfortunately, initiating timely treatment can be difficult. Difficulties are, firstly, patient-related due to lack of knowledge of symptoms and their need for urgency [7-10] and, secondly, physician-related in providing a prompt and accurate diagnosis [11]. The AIHW (2013) report also identified that limited national data exists to address these problems between the onset of patient symptoms and the initiation of early medical treatment [3].In Australia, the International Study of Systems of Care in Minor Stroke and TIA [InSiST] has monitored patient outcomes of both TIA and minor strokes (TIAMS) within a cohort in the Hunter Region since 2012. One of the aims of this study is to derive a TIA predictive diagnostic tool for primary care physicians [12]. This is important as the clinical presentation of neurological symptoms are often complex and subtle, varying depending on the area of focal brain, spinal cord or retinal ischemia [13], and can be difficult to distinguish from non-ischemic causes such as syncope, vestibular dysfunction or migraine [14]. Also, signs and symptoms are often absent on presentation due to reperfusion of the ischemic area [15-17].A primary care predictive diagnostic tool may help address deficits identified within the current literature. These deficits include limited knowledge and consultation time [11], and the subjective use of TIA rating tools [18]. Improvement in the ability to provide accurate and prompt diagnosis of TIAMS is crucial to ensure timely interventions and secondary preventions are initiated and future strokes avoided. Derivation of a diagnostic decision support tool would benefit from a closer understanding of TIA symptomatology and allow refinement of symptom-related variables included in the derivation analyses.To support this research, and to add data from a patients’ perspective, we conducted an analysis of the qualitative portion of data collected in the InSiST cohort study, to construct an insightful description of patient perceptions and responses following the onset of symptoms.

2. Method

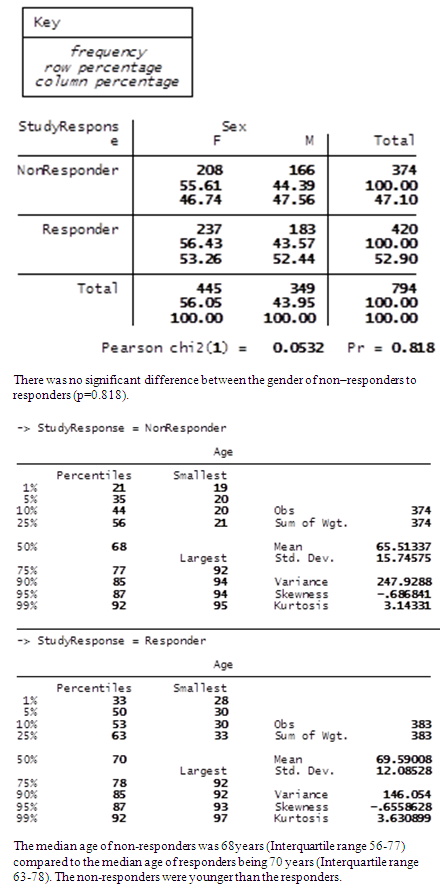

- InSiST is a prospective cohort study. At the commencement of our study, 420 participants were enrolled. Participants were sourced from 16 general practices based on the clinical impression of a possible TIAMS. (Response rate 420/794, 52.9%. For further detail comparing non-responders to responders, see Table 1).

|

2.1. Ethics

- The Hunter New England Research Ethics Committee granted ethics approval for this study (ref no: 12/04/18/4.02). All participants signed an informed consent. To ensure anonymity all identifying details were removed, and pseudonyms were given to the participants.

|

2.2. Data Analysis

- A total of 123 consecutive narratives were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s six phase model, [20] often used in constructivist methodology. This is a recursive process of data familiarisation, data coding, thematic searching, reviewing and developing new themes.During data familiarisation, after the entire data corpus was read and re-read, two voices were observed to be embedded within the narratives. According to Guest et al. this is due to the data collector repeating the same question [21]. To counterbalance this, the research nurse’s voice was dissected from all the stories before patient data familiarisation recommenced.Coding began by clustering together participants’ descriptions, explanations and responses. Together these small descriptive segments exposed how participants interpreted their symptoms. This allowed the analysis to move beyond the identification of common words, to un-covering the participants’ private understanding and constructive processes they used to make sense of their TIA experience [20, 22, 23]. Collectively, mutual patterns of behaviour became visible [20]. These patterns formed latent themes and subthemes, allowing the participants collective story to be told.To ensure rigor at all stages of interpretation, codes were continually data matched to ensure they retained their original meaning [20, 21, 24], and the audit trail and final results were internally reviewed by expert clinicians in the InSiST research team. This was to enhance trustworthiness and clinical relevance of the data.

3. Results

- Two main themes were constructed from the patient narratives: incongruence between symptoms, mental stroke symptom checklist and actions, and symptom based disconnection and inaction, escalating or inhibiting urgent medical treatment.

3.1. Theme 1: Incongruence between Symptoms, Mental Stroke Symptom Checklist and Actions

- Most participants within this study knew that “something was wrong”. Despite each participant’s experience and symptomology being unique, a common set of behaviours developed. The first common behaviour was to seek affirmation through the application of a symptom self-check. How participants responded to their self-check determined the action they took. Symptoms that influenced these self-checks developed into the following sub themes: mental stroke symptom checklist, symptom led action, temporary nature of symptoms, misattribution of symptoms, and inability to describe experience.

3.1.1. Mental Stroke Symptom Checklist

- Some participants immediately associated their symptomology with onset of a stroke. Jean described how she thought that she “was having a stroke [and] went through the mental stroke symptoms checklist”.This awareness enabled participants to draw on their prior knowledge and initiate their own self-check, by aligning their symptoms with a mental stroke symptom checklist. As more of the participant stories unfolded, it soon became clear that the stroke warning signs in their mental stroke symptom check typically included, face, arms and legs, and speech. Participants “looked in the mirror” for “facial droop”, “lifted” their “arms” and checked their “legs for weakness” and they spoke “out loud” to test their speech. Significant others in the participant’s life also demonstrated this behaviour. Maria, one participant’s spouse asked her husband to “squeeze [her] hands”.From the patient narratives, it is not clear how all these participants formulated their mental stroke symptom checklist. Symptoms described were similar to the stroke health awareness media campaign FAST (face, arms, speech, time), though no direct reference was made. A few participants drew their knowledge from past experiences. They describe it as “similar” or “another turn”. Four participants drew their knowledge from their healthcare backgrounds. Three of these four considered “the possibility of a TIA”.For some participants, the use of a mental stroke symptom checklist was useful and led to immediate action. For others, the mental stroke symptom checklist proved inadequate in classifying their symptoms and led to confusion, which is further discussed below.

3.1.2. Symptoms Led Action

- Not every participant experienced all of the symptoms on their mental stroke symptom checklist. For some participants, the realisation that they might be experiencing one symptom of a stroke was enough to prompt immediate medical treatment. Conversely, other participants who experienced only one symptom de-escalated the seriousness of their event and the need for treatment. Marcus describes how he suddenly “lost his balance” and felt “drunk”. Marcus identified a problem with his legs but no further symptoms. Marcus assumed all areas of his mental stroke symptom checklist needed to be experienced to confirm the diagnosis of stroke. Unfortunately, as a consequence, no action was taken. Instead, Marcus “staggered” home, showered and went to work.

3.1.3. Temporary Nature

- Symptoms were specifically reported by half of the participants in this study as having appeared “suddenly” throughout different areas of their body. Liam describes the event; “it was like the brain had been switched off suddenly” then “switched back on” as symptoms resolved. The resolution of symptoms resulted in participants expressing both confusion and, not surprisingly, relief. Sean explained how yesterday he “was convinced” that he had experienced a stroke but today he was “back to normal”. The temporary nature of Sean’s symptoms did not align with his mental stroke symptom checklist. Inadvertently, this can lead to indecision and hesitation in seeking treatment. Many participants expressed, “there was [now] no need to worry”, they “felt better” and “everything was back to normal”. They decided not “do anything about it for a while”. Even Lucinda, who had called an ambulance and had medical treatment at her door, “declined going to hospital” because she “felt normal again”. Two participants with healthcare backgrounds also illustrated this lack of urgency despite both participants correctly considering the origins of symptoms being a TIA. Dereck, was “concerned… about his wife’s symptoms” then became “not worried as [her] symptoms resolved”. Understandably, Dereck expressed a feeling of relief, yet he then failed to initiate a response. For Reese, another health professional, the temporary nature of symptoms led to the self-attribution of a new erroneous diagnosis.Only one participant in the study demonstrated an understanding of the transient nature of a TIA. Brennan explained how his symptoms “righted themselves” when the “blockage was now clear”. These stories suggest that the characteristic temporary nature of TIA symptoms causes considerable confusion, as many still poorly understand the pathophysiology behind a TIA and increased risk of future stroke.

3.1.4. Misattribution of Symptoms

- Not all participants used a mental stroke symptom checklist to seek affirmation of their symptoms. Other self-tests were initiated, including the “Romberg’s test”, “BP” and “neurological exams”. One participant, Boston, oddly specified that “surely …. an appropriate test” would be to “drive.” These self-tests did not conclude the diagnosis of a TIA or even a “mini stroke” or “slight stroke”. Instead, participants decided upon other origins for their symptoms. Misattribution behind symptoms varied, from “neck soreness”, “new shoes”, “high stress…, bending over” and “dehydration”. These opinions facilitated alternative actions, from “having a cup of tea”, taking “two panamax (paracetamol),” and going to bed, to having their “ears syringed”, refusal to take “the new pill anymore”, or going to see alternative health professionals. Interestingly, of the stories that involved misattribution, a strong commonality emerged when symptoms involved visual disturbances. These disturbances led to actions such as "inspection” of the eye and/or an eye “wash”. Myles decided to give his “eyes a work out” by playing Solitaire on the computer. Misattribution directly delayed seeking medical treatment.

3.1.5. Inability to Describe the Experience

- Some participants noted a non-specific change in their usual well-being and described these as feeling “off”, “crook”, “so sick” and “really unwell”. Many other participants could not pinpoint the exact feeling but they knew they felt “funny”, “weird”, “strange” or “overcome”. There were no self-checks available to align any non-specific feelings. The feeling of being overcome or overwhelmed could be one emotional experience that could conceivably correspond with, and lead to, inaction and indecision. Indeed, for Karen, her “blip in brain function” left her feeling “bewildered” and wondering “what was that?” This feeling of puzzlement certainly led her to hesitate and this indecision resulted in a delay in taking action. Karen endured another two of these “funny turns” within the same week before she initiated treatment. Fortunately, not all participants succumbed to inaction due to the unavailability of a self-check. The concern of some participants led to the formulation of symptom lists and use of the search engine “Google”. Participants commented that “Google came up with some worrying diagnoses” that prompted immediate action. Other participants sought advice from the “After Hours Chemist”, the health information service “Health Direct”, the “practice nurse”, “GP receptionist”, their partners, “housekeeper”, or family members.This demonstrated the variability in responses to events and that some participants, through use of their own self-direction, were more capable of recognising the need to take action.

3.2. Theme 2: Symptom Based Disconnection and Inaction

- Some participants described how their symptoms inhibited their ability or need to take action. For many, the severity of their symptoms removed their capability or cognitive ability to seek help. For other participants, they dismissed or ignored their experience, rejected that the event took place, and arrived at the conclusion that there was no need for urgent medical treatment. This symptom based disconnection placed all of these participants at risk of harm. The varying degrees of disconnection led to the following subthemes: body not reacting; knew what they wanted, but no idea how; minimisation and denial; surrender; and no awareness of symptoms.

3.2.1. Body not Reacting

- Some participants described their experience as becoming “disconnected to the world”. Although the degree of disconnection varied, all participants were aware that something was happening and they were unable to share their experience with others due to the way their event affected their use of language and body control. For some participants, they knew what they wanted to say but “could not get [their] words out”. Their language was either absent, “jumbled”, “gibberish” or “slurred.” All of which, characteristically describe known language deficits for TIA and minor stroke. However, when viewed through the eyes of the participants, these symptoms now take on new meaning, as participants had become verbally incapacitated and unable to initiate medical treatment. For some participants, this disconnection spread throughout their body. Murray could not stand up or do anything but sit with his head in his hands. He describes this experience as his “body [being] out of control”. Similarly, Lorenzo’s “body was not reacting to what the brain was saying”. While travelling on a plane, Lorenzo remembers thinking that he “should call out for help or reach for the [assist] button”, but he “wasn’t capable of turning [his] head and shouting or even reaching out to the passenger next to him”. He thought he “was going to die”. Lorenzo’s loss of body control meant that he did not have the capacity to help himself. His powerlessness led to a direct consequence, inaction. Indeed, for many participants, the ability for them to seek urgent medical treatment dissipated.

3.2.2. Knew what They Wanted, but no Idea how

- The inability to perform an action varied among participants. Anna explained that she walked over to open the Venetian blind but “didn’t know how”, Lex tried “to get the harness off the dog, [and] could not”; Dion “fiddled and fiddled”, but kept putting his tie on “back to front”.These participants were all aware of what needed to be done but they were all unable to successfully complete their tasks. The process of gaining medical treatment also required the completion of a series of specific actions, an act that each of these participants was incapable of performing.

3.2.3. Minimisation and Denial

- Despite participants being able to fully describe their experience and the emotional responses it evoked, some “chose not to think about what had happened” and minimised or denied their symptoms. Lorenzo who became locked within his body “thought he was going to die” and concentrated on the only thing he could do, which was to; “breathe heavily in and out”. Then, when his symptoms subsided, incredibly, he went to work. Perhaps the emotional after-effect of the TIA experience generated strong feelings of helplessness and vulnerability. Going to work gave some control back to Lorenzo. Work was familiar and routine, and Lorenzo appeared to use minimisation of the event as a coping mechanism to buffer the emotional effects and to avoid the confrontation of his reality. Lorenzo’s disconnection from his symptoms meant that he did not have to deal with his experience, thus preventing any initiation of action.Denial could also result in inappropriate actions. Boston “stubbed his toe twice on the carpet” which led him to notice his foot was “slapping” on the ground. To improve his gait, he decided he “could walk better when dragging the foot”. Alarmingly, despite his realisation that his foot was not working, he went to his car and drove. The act of driving was a common occurrence throughout the participants’ narratives, despite being well aware that something was “very wrong”. Claire drove to church using her “good eye”; Abdull drove after his speech went “haywire”; Barry after going temporarily “blind” and Mark after stumbling and falling forward. Regardless of what symptoms participants experienced, these participants minimised or denied their symptoms, placing themselves, and others, at risk.

3.2.4. Surrender

- A small number of participants also surrendered to the fact that they may have had a stroke or similar event. They knew that something was happening to them that was out of their control. Instead of taking actions to seek help, they instead accepted what was happening and allowed the event to unfold. Raj “remained seated and waited to see what was going to happen next”. This surrendering, also led to passive resistance. Scott describes his thoughts, “if it is a stroke, it will either take me out or it won’t”. He “did not want to go to hospital” so he “just laid there”. Scott recognised his reality and did not attempt to change it. Tori, similarly, illustrated her acceptance. Tori remembers thinking to herself “this must be dying and it’s not too bad”.

3.2.5. No Awareness of Symptoms

- Not every participant noticed that something was wrong, and therefore did not recognise the need to seek timely medical treatment. Participants “drifted off into a fuzzy state”, “blacked out”, “slumped” and “collapsed on the floor” with “no memory how [they] got there”. The debilitating nature of symptoms resulted in these participants being reliant on significant others in directing them to gain urgent medical attention. Significant others noticed the participants “talking funny” or “not look[ing] alright”. Umar describes that if he “had been home alone [he] may never have known about this TIA”. However not all significant others noticed the participant’s symptoms and acted accordingly. Gwen’s son was concentrating on the computer and “didn’t notice mum’s problems.” This resulted in a delay in seeking medical treatment.

4. Discussion

- Most participants within our study were able to recognise the sudden onset of their TIA symptoms, though their interpretation of symptoms varied, influencing their health seeking behaviour. These behaviours facilitated our two main themes: incongruence between mental stroke symptom checklist and actions; and symptom led disconnection and inaction.Some participants immediately suspected they were experiencing a stroke. To confirm, they referred to a mental stroke symptom checklist, which included face, arms and speech. Of note, no direct reference was made to the National public health campaign FAST (face, arms, speech, time), that has been promoted in Australia since 2006 [25]. This is important to highlight as FAST is targeted at improving community awareness of the common symptoms of stroke and the importance of seeking urgent medical treatment to achieve optimal outcomes [26]. It is not generally promoted for its relevance to TIA.For some participants, the use of a mental stroke symptom checklist was straightforward, facilitating prompt action. Reinforcing the importance of symptom recognition to reduce a delay in health seeking behaviour [10]. However our study also identified that symptom recognition does not always prompt action. Similarly, two systematic reviews on patient responses to TIA symptoms, found no association between symptom recognition and health seeking behaviour [27, 28]. Even when personal or family history was identified [29]. This highlights a lack of public awareness on the importance and urgency of medical treatment [3, 30]. Interestingly, an Australian study has established that if patients appraised their symptoms as serious, there was less delay in seeking medical attention [30], an important point that could be used to promote timely treatment. Symptom recognition and independent health seeking behaviour was also hindered by the transitory experience of symptoms [31]. In our study, only three participants considered the possibility of a TIA. Remarkably, these participants all had healthcare backgrounds, but when their symptoms subsided, they downplayed the event, overlooking the last component of the FAST mnemonic, timely action. This perhaps suggests a lack of knowledge on TIA pathophysiology, prognosis and the need for intervention. Our study also identified other deficits in the way participants utilised their stroke checklist. Some participants believed that they needed to experience all of the symptoms, while others became confused as to why their symptoms were not included. This identifies incongruence between the mental stroke symptom checklist and actions taken, resulting in participants re-evaluating their stroke diagnosis, using alternative checklists, de-escalating the seriousness of their event, considering alternative causes and delaying medical treatment. An analysis of public awareness of the FAST campaign in the UK identified face, arms and speech to be most commonly associated with stroke, while leg weakness and visual problems were the least recognised [32]. FAST purposively does not contain all stroke symptoms so it can be easily remembered by the layperson [33]. Instead, it focuses on three common symptoms drawn from the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale [34]. Strokes occur more often in the anterior circulation, therefore FAST symptoms focus on anterior circulation deficits rather than posterior circulation deficits [35]. The clinical presentation of posterior circulation deficits includes visual disturbances, dysphagia, vertigo, altered levels of consciousness or hearing loss [36]. Notably, not all studies agreed with these differences between anterior and posterior circulation deficits [35] and believe less common symptoms are usually experienced in combination with at least one FAST symptom [33]. However, in our study, many of our participants’ narratives described their visual disturbances only. More importantly, public awareness on seeking urgent medical treatment for visual disturbances was low [37]. When there was an absence of the commonly promoted stroke symptoms, face, arms and speech, [8] or when symptoms were less dramatic than those promoted in public stroke awareness campaigns [38], or expected of stroke, there was a delay in seeking medical treatment [39].The focus of current evidence is predominantly on the physical symptoms of stroke and TIA rather than the non-focal deficits patients’ experience [40]. In our study, many participants focussed on these non-focal symptoms in their description of their experience. We noted a commonality in narratives where participants lost their ability to initiate medical treatment due to the sudden loss of language and bodily control, inability to perform tasks, unawareness of symptoms and lost consciousness. Although these findings are not new, the seriousness of these TIA symptoms remains poorly identified within the literature. Interestingly, the analysis on phone calls to emergency services highlighted the seriousness of TIA symptoms. Callers were concerns over collapses and falls which are the outcome of stroke symptoms, rather than making direct references to their stroke symptoms [41]. Excluding the subjective experiences from physical symptoms excludes capturing all of the diagnostic information available [40]. For example, other qualitative studies suggest having no awareness of symptoms is a diagnostic TIA symptom [40], and the minimisation of symptoms may be due to a disruption between mind and body communication [42]. Therefore, it may be prudent to consider ways to include the subjective experience of patients in health promotion messages as this may broaden the understanding of TIA within the community.

4.1. Limitations

- Like all qualitative research, we do not claim transferability of our study findings to the wider population. Our study methodology embraced the participants’ TIA experience within their own particular context or setting. Retrospective recall by participants may have also been impaired due to the impact TIA symptoms have on cognitive ability and delays in the initial InSiST interview. Working from transcribed narratives can also be linguistically subjective. To avoid this, several authors internally reviewed all stages of data analysis.

5. Conclusions

- Through the exploration of patient narratives we were able to capture a unique patient perspective on how patients perceived and responded to their TIA event/experience, as well as highlighting deficits in how stroke checklists are being utilised by the public. This included the need to experience all symptoms, confusion over additional symptoms, symptoms that could not be described, or the temporary nature of symptoms. Together, such experiences appeared to deescalate the seriousness of symptoms, or aid the formation of erroneous diagnoses that facilitated inappropriate actions. The identification of deficits in how stroke checklists are being utilised, has implications for both current public health stroke campaigns and future education about TIA awareness. There were several common threads in the participants’ narratives. These threads identified symptoms that were potentially serious, and hindered participants’ capability and cognitive ability to seek help. Symptom-based disconnection and having no awareness of symptoms left participants incapacitated to take action, placing these participants at risk and making them reliant on significant others to gain appropriate support. It is important that healthcare professionals identify and acknowledge these subjective patient experiences, as they provide additional diagnostic information that may contribute to more accurate detection and diagnosis of TIA in the future. Further studies exploring the subjective experiences of TIA symptoms would be beneficial to increase our understanding of TIA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The National Health and Medical Research Council fund the InSiST study. We would like to thank all participants, General Practice physicians and practice nurses for their support. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML