-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2016; 6(2): 45-51

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20160602.03

A Study to Evaluate the Utility of Using Opportunistic Screening for Hypertension in Primary Care Settings Using a Two Phase Study Design

Mitasha Singh1, Shailja Sharma2, Sunil Kumar Raina1

1Department of Community Medicine, DR. RPGMC, Tanda, Kangra (Himachal Pradesh), India

2SIHFW, Cheb, Kangra (Himachal Pradesh), India

Correspondence to: Sunil Kumar Raina, Department of Community Medicine, DR. RPGMC, Tanda, Kangra (Himachal Pradesh), India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

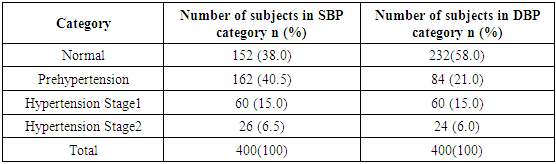

Opportunistic screening may serve as an effective tool for estimating the burden of a disease. In case of diseases like hypertension, a simple non-invasive modality (BP measurement) is used in quantifying the burden. The study examined the utility of developing opportunistic screening as a modality for hypertension in a primary care setting. It was conducted in two phases. Phase 1 estimated of burden of hypertension in a tertiary care centre in a rural area of North West India. 424 attendants accompanying patients suffering from episodic illnesses of 2-3 days in outpatient departments of the hospital were invited to participate and 400 (94.3% response rate) were screened for blood pressure (BP), height and weight. The second phase of the study comprised of comparative assessment of studies across India in rural setting. As per the JNC VII criteria for classifying hypertension 40.5% (162/400) were pre hypertensive, 15% (60/400) were in Stage 1 hypertension and 6.5% (26/400) in Stage 2 hypertension, with a total of 21.5% hypertensive subjects. Prevalence of hypertension in various studies conducted across India in rural settings give a range from 5-40% with a mean prevalence of 25.63%. Hence, opportunistic screening can be used as a useful tool to screen for early detection of hypertension and also to raise awareness about it in a primary care setting.

Keywords: Utility, Opportunistic screening, Hypertension

Cite this paper: Mitasha Singh, Shailja Sharma, Sunil Kumar Raina, A Study to Evaluate the Utility of Using Opportunistic Screening for Hypertension in Primary Care Settings Using a Two Phase Study Design, Public Health Research, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 45-51. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20160602.03.

1. Introduction

- Screening in medicine, is used to identify an unrecognized disease in individuals. Generally screening is conducted as an organised programme. To be effective, screening programmes have to be of a high standard, and the screening services need to checked and monitored by people from outside the programme. With organised screening programmes, everyone who takes part is offered the same services, information and support. Often, large numbers of people are invited to take part in organised screening programmes. In comparison opportunistic screening happens when someone asks their doctor or health professional for a check or test, or a check or test is offered by a physician or health professional. Unlike an organised screening programme, opportunistic screening may not be checked or monitored. However opportunistic screening may serve as an effective tool for estimating the burden of a disease particularly in a primary care setting. [1] This assumes more significance in case of diseases like hypertension, wherein a simple non-invasive modality (BP measurement) is used to quantifying the burden. Developing opportunistic screening as a screening modality will be helpful in planning prevention as it allows health practitioner at the primary level to use his or her numerous contacts with the clients. [2]One of the factors usually associated with increasing burden of non-communicable diseases like cardiovascular diseases is inability to obtain preventive services. [3] This is true for hypertension as well. In spite of the efforts; prevention, early detection, treatment and control of hypertension is still suboptimal and unsatisfactory not only in developing countries like India but also in well developed countries. [4]One of the cornerstones of the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases has been early detection. To improve early detection, recording blood pressure of every individual who comes in contact with health practioners as part of opportunistic screening will be helpful.The present sought to assess the utility of developing an opportunistic screening programme for hypertension for use in primary care settings in India. For this we used opportunistic screening as a tool for estimating the burden of hypertension in our population and then establishing a comparison with other population based studies conducted across rural India.

2. Methodology

- The study was conducted in two phases; phase 1) burden estimation and phase 2) comparative assessment to establish utility of opportunistic screening.Phase 1: The phase 1 of the study comprised of estimation of burden of hypertension which was carried out from February through April 2014 in a tertiary care centre in a rural area of North West India. It was conducted in a case study mode using convenience sampling. Attendants of patients suffering from episodic illness of 2-3 days such as respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, fever etc., in Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Surgery outpatient department were included in the study after taking their consent. 424 attendants were invited to participate in the study, of which 410 gave their consent. All the participants were 18 years and above, and were made aware of the purpose of the study. Variables included age, sex, weight, and height. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured. History of hypertension or diabetes was taken, and if positive for either or both, subject’s phone number was recorded and was asked to bring their physician’s prescription on their next visit to the centre or fax it on the number they were given. A total of 10 non-responsive subjects whose history could not be confirmed were excluded from the study. Thus, only 400 (94.3% response rate) out of a total of 410, willing to participate were included as the final sample size of the study.Weight and height were measured using standard procedures. Weight was measured using standardised portable scale. The subjects removed their shoes and heavy clothing while weighing. Height was measured using a stature meter. To record the height, the subjects stood with their scapula, buttocks and heels resting against a wall, the neck was held in a natural not stretched position, the heels were touching each other, the toe tips formed a 45° angle and the head was held straight such that Frankfurt plane was horizontal. BMI was determined using the Quetlet’s equation (ratio of weight in kg and square of height in m). The cut off values for defining obesity are in accordance with the guidelines given by the WHO, and these were further compared with the values calculated according to the consensus statement for Indians (i.e., 18-22.9 kg/m2 normal, 23-24.9 kg/m2 over weight, >25 kg/m2 obese) for comparison. The consensus statement presents the revised guidelines for the diagnosis of obesity, the metabolic syndrome and drug therapy and bariatric surgery for obesity in Asian Indians. [5] The BMI cut-offs as per WHO guidelines were used to compare the consensus statement. [6] Blood Pressure was measured after 10 minutes’ rest, with subjects in a seated position using OMRAN digital automatic BP apparatus. Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure (SBP & DBP respectively) were measured with 2 readings. The average of two readings was recorded. The cut off values for hypertension were taken according to the values given in Joint National Committee VII. Person having systolic BP between 120-139 and / or diastolic BP 80-89 was labelled to have pre-hypertension. Stage1 hypertension was taken as systolic BP between140-159 and/ or diastolic BP between 90-99 mmHg. Stage 2 hypertension was taken as systolic BP > 160 and/ or diastolic BP > 100 mmHg. [7] Subjects with pre hypertension and hypertension were advised to visit a physician and arrangements for the same were made by the investigating team. All statistical analysis was performed using Epi Info version 7. Descriptive statistics for obesity indices were calculated for both men and women. Differences in BMI between genders were tested with Student’s t test. Correlation coefficients between BMI, SBP and DBP were calculated by Pearson correlation analyses. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Phase 2: The second phase of the study comprised of comparative assessment of studies conducted across India in rural setting. A search on ‘Pubmed’ was made with combinations of medical subject headings (MESH) that included search items such as ‘hypertension’, ‘prevalence’, ‘rural’, ‘tribe’ and ‘India’ conducted in last 10 years. The search yielded a total of 35 studies, which were filtered according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. We identified articles eligible for further review by performing an initial screen of identified titles or abstracts, followed by a full-text review. Articles were considered for inclusion if the study was cross sectional; study conducted among adult population (> 18 years old); studies were on prevalence; burden of HTN; conducted in a rural setting in India; criteria used for HTN was same as used in our study in phase 1. Articles were excluded if they were letters or abstracts; not conducted on humans; and not community-based studies. A total of fourteen eligible studies were included in the comparative assessment.

3. Results

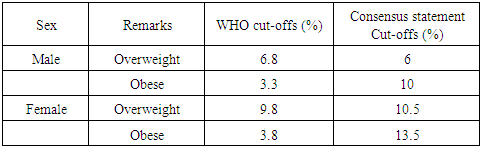

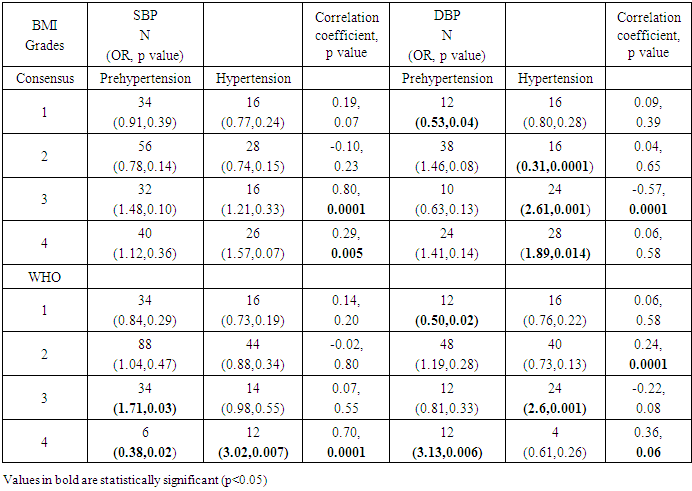

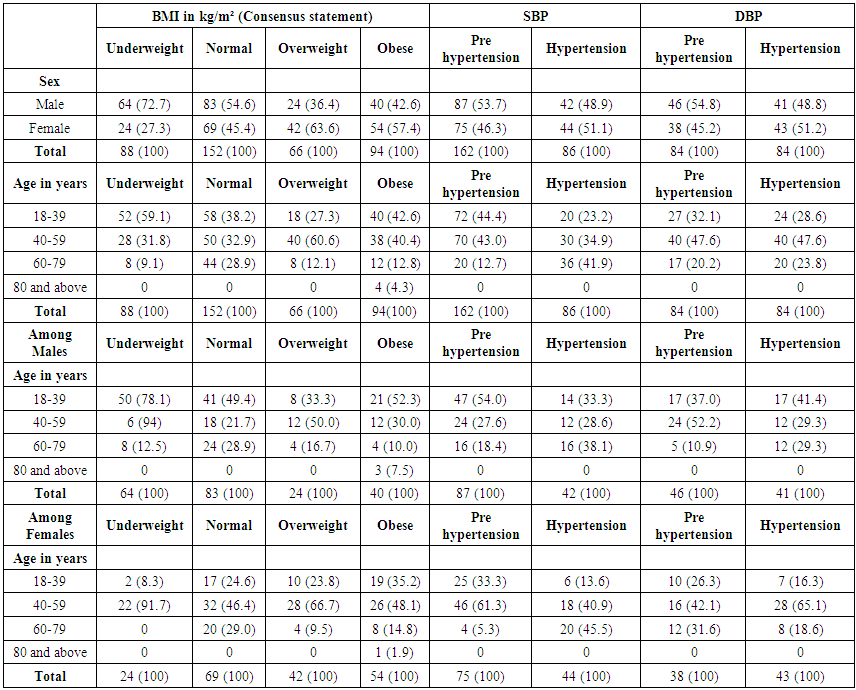

- The mean age of 400 participants was 43.02 (±13.50) years ranging from 18-85 years old. Males comprised 52.8% (211/400) of the study population. The mean BMI for females 22.97±5.05 kg/m2 was higher than those of males 21.43±4.42 and the difference was statistically significant (p=0.001). Twenty seven percent (27%; 108/400) of the subjects had their blood pressure checked in recent past (3 months) and 5.8% (23/400) were diagnosed hypertensive by a physician and were already on medication. As per the JNC VII criteria for classifying hypertension 40.5% (162/400) were pre hypertensive, 15% (60/400) were in Stage 1 hypertension and 6.5% (26/400) in Stage 2 hypertension, with a total of 21.5% hypertensive (Table 1). According to World health organization (WHO) classification for overweight and obesity, 16.5% (66/400) were overweight and 7% (28/400) obese. As per WHO consensus statement for Indians the 16.5% (66/400) of study population were overweight and 23.5% (94/400) were obese. Table 2 shows the comparison of WHO and consensus statement classification in male and females. Three fifth of the overweight and obese subjects were females. About half of the overweight and obese and majority of pre hypertensive and hypertensive subjects (47.6%) belonged to 40-59 years of age group. A higher proportion of pre hypertensives were males (54.8%) and a marginally higher proportion of hypertensive subjects were females (51.2%) (Table 3). We see an increase of 6.7% among males who were classified as obese and an increase of 9.7% among females who were obese on using the consensus statement. Both SBP and DBP were imperfectly positively correlated with BMI. A statistically significant correlation with DBP (r= 0.177, p= 0.0001) and non-significant with SBP was noted (r= 0.074, p= 0.137) (Table 4).

|

|

| Table 3. Age and sex wise distribution of BMI (according to consensus statement), Pre hypertension and Hypertension |

|

|

4. Discussion

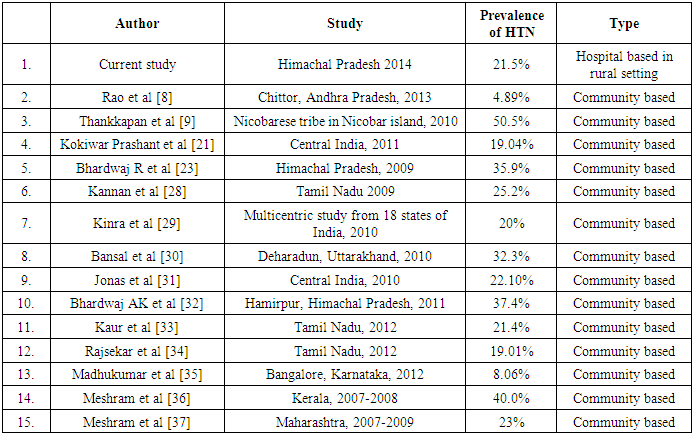

- There are few nationwide studies to determine the prevalence and absolute burden of hypertension in India. [10] In present study, which was conducted in hospital setting, the prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension was 40.5% and 21.5% respectively. With increasing life expectancy, widespread availability of food containing high fat products and increasing physical inactivity, hypertension and its risk factors are now an emerging challenge in the developing countries. [11]Obesity is one of the risk factors for hypertension; and BMI is the most frequently used measure of obesity because of the robust nature of the measurements of weight and height, and the widespread use of these measurements in population health surveys. [12] The mean BMI of our study population was 22.14±4.80 kg/m2. In Secondary analysis of the 2009 adult California Health Interview Survey of 6 Asian subgroups, the mean BMI was highest among Filipinos (25.5 kg/m²). [13] On using the WHO classification for obesity, 23.5% of the participants were classified as overweight or obese, whereas using the consensus statement the figure increased to 40%. Also in our study 60% of females had BMI more than 23. In a study by Anjaneyulu et al on healthy young adults 50% of males and 40% of females screened were found to have BMI more than 23. [14] When a BMI of 25 kg/m² was applied as the cut-off level in a study on 123 healthy North Indians by Dudeja et al, 15.1% of males and 27.0% of females were overweight and obese. [15] Similarly a study by Shailja et al reported 36.8% of overweight and obese, among a healthy young adult population in North India using the consensus statement for Indians to classify obesity. This supports the view that obesity may be underreported in Indian population when using WHO criteria. [16] Asian Indians manifest clustering of cardiovascular risk factors and T2 diabetes mellitus (DM) at lower levels of obesity; hence, the diagnosis of obesity should be made at lower levels of weight for height than in non-Asians. It is estimated that by application of these guidelines, additional 10-15% of Indian population would be labelled as obese or overweight. [17] It will be helpful if revised criteria are used in general and family practice while dealing with the adult population in India.As early as 1967, data from the Framingham Study indicated that obesity is a leading risk factor for chronic arterial hypertension. [18] Similar results in our study indicate a positive correlation of BMI with hypertension, but statistically significant for DBP only. However, a study on 165 menopausal women of Iran showed a significant correlation of BMI with SBP only. [18] In an Australian national study on 11,247 adults a significant positive correlation was studied between BMI and SBP; DBP was not included in the study. [14] Ghosh and Bandyopadhyay conducted a study in Singapore claiming that BMI, Waist Stature Ratio and Waist Circumference had stronger correlations with both SBP and DBP. [20] The second phase on comparative assessment of studies across India in rural setting shows a median prevalence of 22.55% among 14 community based studies which is comparable to 21.5% reported in our study. Urbanization and acculturation could be possible causes of a high prevalence of hypertension and its risk factors in rural areas. [21] Rao et al in their study at Chittor, Andhra Pradesh reported the lowest prevalence of 4.89%. [8] Kokiwar et al., in their study in rural central India reported a prevalence of 19.04% among the age group 30 years and above. [22] Joshi et al., conducted a large cross-sectional study on 15,662 subjects from 8 states of India and reported the prevalence of hypertension as 46.00% in the pooled sample. [23] Bhardwaj et al in a community based survey in rural parts of Himachal Pradesh on 1092 subjects reported a prevalence of 24.45% of prehypertension and 35.89% of hypertension. [24] In a meta-analysis by Midha T et al, the prevalence of hypertension in the rural population was higher in Himachal Pradesh. [25] Highest prevalence of 50.5% was reported by Thankappan et al in their study on Nicobarese tribe. [9] The prevalence of hypertension in rural populations is steadily increasing and is approaching the rates of the urban population. [25] Variation in prevalence reported by studies across the country may be because of the difference in age group, geographical variations and differences in the diagnostic criteria adopted by authors. [22] The average prevalence of hypertension in the rural population, in various community based studies all over India is almost similar to the prevalence reported in the current study in a hospital setting. The famous rule of halves tells us that half of the hypertensive subjects in population are aware of the condition and only about half of those aware are being treated. [26] Opportunistic screening can be used in hospital settings as a tool to screen the healthy population for hypertension and also raise the proportion of aware population. Also not all patients diagnosed with hypertension require medications; life style and diet modification are sufficient to lower the risk of complications. For preventive care the cost of implementing a programme is low, at less than US$ 1 per head in low income countries, less than US$ 1.50 per head in lower middle-income countries and US$ 2.50 in upper middle-income countries. [27] A programme developed in the health system will lead to sustainable development as compared to that developed outside the system. Increasing the quality of good life using cost effective techniques for the population is the primary concern of a public health specialist, for which opportunistic screening can be a useful initiative.

5. Conclusions

- The population screened for hypertension through opportunistic screening in a hospital based setting yielded proportion of hypertension which was comparable to population based studies. Also almost all adults in their lifetime visit a health centre. If at these visits their blood pressure is recorded and followed up accordingly, early intervention can be planned and initiated to reduce the burden of Hypertension and associated diseases. In this way any contact with a primary care health care practitioner can be utilised for developing early intervention.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML