-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2015; 5(5): 144-152

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20150505.04

Maternal Health and Social Determinants: A Study in Jammu and Kashmir

Nadiya Muzaffar

Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (U.P.), India

Correspondence to: Nadiya Muzaffar, Department of Sociology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (U.P.), India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Maternal health is a key indicator of women’s health and status. The bio-medical theories attribute health to several biological and medical factors. The social determinant theories, on the other hand, have established that the social circumstances play dominant role in deciding health, morbidity and health care delivery. Social practices, like patriarchy, create long term social deprivations. The Ottawa Charter of Health Promotions passed in 1986 recognizes peace, shelter, education, food, income, a harmonious eco-system, resources, social justice and equity as essential pre-requisites for health. Situated within this background, this paper locates the status of maternal health in Jammu and Kashmir, the northernmost state of India and identifies the social determinants of maternal health. This work is based on the secondary sources in general and the data provided by District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), India in particular. The data shows that place of delivery (government hospital, private clinic or home) is not a major determinant of delivery complications but the socio-cultural background like education, income and place of residence are important determinants. Even institutional delivery increases with the education level and wealth of the women. Rural-urban gap in institutional delivery was seen to be 35.9 percent. Despite being a comparatively richer state, anaemia is a very important determinant of maternal health in the state. The paper concludes that policy intervention is required to ensure empowerment, freedom, peace, justice and inclusion of women for sustainably improving the maternal health.

Keywords: Antenatal care (ANC), Pregnancy care, Delivery complication, Maternal health, Social determinants

Cite this paper: Nadiya Muzaffar, Maternal Health and Social Determinants: A Study in Jammu and Kashmir, Public Health Research, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 144-152. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20150505.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

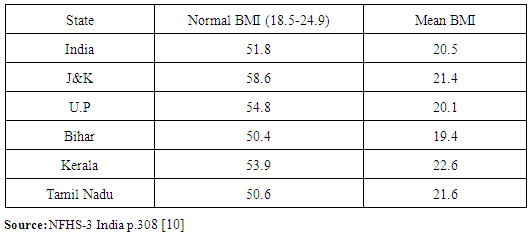

- Gender based structured inequality is a common feature of any patriarchal society. A patriarchal society like India poses several challenges for the females. Health inequality is one more typical inequality faced by women in India. The adverse sex ratio, female feticide, high maternal mortality, widespread prevalence of anemia and poor access to quality institutional delivery are some of the manifestations of sex selective health deprivation faced by women in India. The bio-medical approach, the dominant discourse responsible for taking care of the health and healthcare needs of the population in most of the developing countries, is largely insensitive to the gender or other socio-cultural divides prevailing in the human societies [1, 2, 3]. The growth of the social determinants approach, in the fields of health and healthcare, is increasingly becoming an alternative discourse to understand the social deprivations faced by several disadvantaged groups including the females. Maternal health is an important indicator of women’s health and status. The World Health Organization (2009) in Women and Health: Today’s Evidence Tomorrow’s Agenda [4] defines maternal health as the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. Often motherliness seems to be a positive and fulfilling experience, but for too many women it is linked with suffering, ill-health and even death. Human history, all the way through has witnessed death and disability both among women and the neonates due to pregnancy and childbearing. Although a number of attempts are made at the global level in order to reduce maternal death and disability and a lot of solutions are now readily available to save a pregnant woman’s life yet there are thousands of women who continue to lose their lives each year due to poverty, ineffective health systems, and deep-seated gender inequalities that do not allow women to make informed, independent decisions to protect their health [2, 5, 6]. The social determinants approach helps us to understand these deeply structured social variables which play a very important role in deciding health of a woman especially during the reproductive period.In the overall Human Development Index, Jammu & Kashmir ranks 10th among the Indian states [7]. It is noteworthy that among the three components of HDI, Jammu & Kashmir performs better than the national average on Income Index and Education Index but Health index of Jammu & Kashmir is below the national average and far below than Kerala. Looking at the sex ratio in Indian states, Jammu & Kashmir has the second worst sex ratio i.e. only 883 females per 1000 males in 2011 [7]. The typical and adverse sex ratio of Jammu & Kashmir, lack of information about Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), poor educational attainments, the patriarchal cultural patterns, and the impact of political violence on the social order makes it very important to understand the state of health of women in general and the maternal health of women in particular in the state. Jammu and Kashmir is an important state of India and presents unique climatic and cultural conditions. Its demographic pattern differs from that of rest of the country with Muslims accounting for 56 percent of the population in 2007-08. The Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in 2008 was 2.2 which in rural areas is quite high (2.5) as compared to urban areas (1.5). Looking into the performance of indicators related to human development, Jammu and Kashmir has the lowest incidence of poverty compared to all other states in the country. Education has been affected due to the political and social disturbances. The literacy rate of Jammu and Kashmir is only 68.7 percent, against the national literacy rate of 74 percent in 2011. Based on extensive review of literature and analysis of secondary data provided by the District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3) [8, 9] and the National Family Health Survey-3 (NFHS-3) [10, 11], the present paper looks at the issues related to maternal health in Jammu and Kashmir from the social determinants of health perspective.This study aims to fulfill the following objectives:• To describe the pregnancy care and delivery complications in Jammu and Kashmir.• To locate the status of maternal health in Jammu and Kashmir.• To identify the specific social determinants of maternal health in Jammu and Kashmir.• To suggest recommendations for improvement in maternal healthcare and related social determinants.

2. Methodology

- This is a review paper based on secondary sources and analysis of data provided by District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3) [8, 9]. The DLHS-3 is a nationwide survey covering 601 districts from 34 states and union territories of India. This is the third round of the district level household survey which was conducted during December 2007 to December 2008. The survey was funded by the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).This report is based on data collected from 17,858 households from Jammu & Kashmir during 2007-08 [9]. From these households, 15,175 ever married women aged 15-49 years and 7,189 unmarried women aged 15-24 years were interviewed. The main instrument for collection of data in DLHS-3 was a set of structured questionnaires, namely, household, ever married woman, unmarried woman and village questionnaires. Sub Centre, Primary Health Centre (PHC), Community Health Centre (CHC) and District Hospital (DH) questionnaires were used to conduct the facility survey. The data present in the report has been analysed by the author. The author has drawn different results from her own analysis that were not present in the report.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Maternal Health

- In the International Classification of Diseases and related health problems, (ICD-10), WHO defines maternal death as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes” [12]. Pregnancy and childbirth are of course not diseases. But, they carry risks because of the varying and embedded complications, practices, processes, beliefs, life conditions and the immediate environment. These risks can be reduced by health care interventions such as the provision of maternal and public health care, supplementary nutrition, family planning, safe abortion and improvement in other reproductive conditions.Improving maternal health is one of the three health related goals out of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that were established following the Millennium Summit of the United Nations in 2000, under the United Nations Millennium Declaration [13]. Under MDG goal-5, countries are committed to reducing maternal mortality by three quarters between 1990 and 2015. However, between 1990 and 2013, the global maternal mortality ratio (i.e. the number of maternal deaths per 100 000 live births) declined by only 2.6 percent per year. This is far from the annual decline of 5.5 percent required to achieve MDGs.Maternal health care includes antenatal care, delivery care and post natal care, postpartum complications and maternal care indicators. The characteristics of individual women like age, residence, income, number of previous pregnancies, the health system available to them, and education level play a significant role in determining whether they seek appropriate services. A woman’s age, the number of children she has already had, her knowledge of services, and previous birthing experience can all influence pregnancy and delivery care [14]. A woman’s level of education, her specific knowledge about the importance of pregnancy and delivery care and awareness of where to receive them also plays a role in uptake of services [15]. Caste, wealth quintile, and urban or rural residence were all found to be associated with quality of antenatal services received by different groups in India [16].According to NFHS-3, antenatal care (ANC) refers to pregnancy-related health care, which is usually provided by a doctor, an Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM), or another health professional. Ideally, antenatal care should monitor a pregnancy for signs of complications, detect and treat pre-existing and concurrent problems of pregnancy, and provide advice and counseling on preventive care, diet during pregnancy, delivery care, postnatal care, and related issues. The main purposes of antenatal care are to prevent certain complications, such as anaemia, and identify women with established pregnancy complications for treatment or transfer [17]. In India, the Reproductive and Child Health Programme aims at providing at least three antenatal check-ups which should include a weight and blood pressure check, abdominal examination, immunization against tetanus, iron and folic acid prophylaxis, as well as anaemia management. As per NFHS-3, the most commonly reported pregnancy-related health problems are excessive fatigue (48 percent) and swelling of the legs, body, or face (25 percent). Ten percent of mothers had convulsions that were not from fever and 9 percent reported night blindness. Only 4 percent women had any vaginal bleeding. The report also reveals that every woman who had a birth in the five years preceding the survey was asked if she had massive vaginal bleeding or a very high fever—both symptoms of possible postpartum complications—at any time during the two months after delivery of her most recent child. Women reported massive vaginal bleeding for 12 percent of births and a very high fever for 14 percent of births [2].

3.2. Maternal Health in Jammu and Kashmir

- According to NFHS-3 [11], the percentage of Antenatal Care visits by women in Jammu and Kashmir is better than the national average. In Jammu and Kashmir 84.6 percent women had at least one ANC visit and 73.5 percent had three or more ANC visits. Besides, 54.8 percent women had an ANC visit in first trimester. At the national level these figures were found to be 76.4 percent, 52 percent and 43.9 percent respectively. Although Jammu and Kashmir was seen to be performing better than some poor performing states like Bihar (one ANC visit=34.1 percent & 3 or more ANC visits= 17.0), Uttar Pradesh (one ANC visit=66.0 percent & 3 or more ANC visits= 26.6) etc, it was far behind from the better performing states like Kerala (one ANC visit=94.4 percent & 3 or more ANC visits= 93.6) and Tamil Nadu (one ANC visit=98.6 percent & 3 or more ANC visits= 95.9).The NFHS-3 data also suggests that there are multiple sources of receiving the ANC services both at national level and in Jammu and Kashmir. As compared with the national average where 50.2 percent women received their ANC from doctors, 23 percent received from ANM/Lady Health Visitor (LHV)/nurse, 1.2 percent women from Dai/ Traditional Birth Attendant (TBA) and 22.8 percent received ANC from no one, majority of women (77.2 percent) in Jammu and Kashmir received their ANC from doctors, 6.2 percent from ANM/LHV/nurse, 1.1 percent from Dai/TBA and 14.7 percent from no one. However in Kerala 98.1 percent and in Bihar only 22.5 percent women received their ANC from doctors.The prevalence of institutional delivery is 55 percent in Jammu & Kashmir as compared to the national average of 46.9 percent as per the DLHS-3 data. About forty four percent women in Jammu and Kashmir had home delivery (national average=52.4 percent). However, institutional delivery in Kerala was 99.4 percent and in the states of Bihar and U.P., the corresponding figures were 27.5 percent and 24.5 percent respectively.

|

3.3. Maternal Health and Social Determinants

- Health is determined by various social, economic, political, cultural and environmental factors (together identified as social determinants) and not just by the biomedical ones. There are growing evidences which propose that health outcomes can be improved by working on these social determinants of health [18]. Michael Marmot (1999) [1] argues that the environment influenced by social and economic factors is partly responsible for the health condition and factors such as childhood environment, the work environment, unemployment, patterns of social relationships, social exclusion, food, addictive behavior, transport, etc., have an impact on the medical care system and the differing disease rates within and between countries. Culture also plays an important role in health and illness. In India, there are culturally accepted notions, rites and rituals, related to health and healthcare practices.Chadwick’s ground-breaking work on the sanitary condition of laboring population in Great Britain indicated that non-biomedical factors are accountable for the incidence of disease and pestilence in the 19th century [3]. McKeown’s [19] influential thesis on the role of non-biomedical determinants for the decline of mortality rates in England and Wales during the 19th century toughened these linkages which led to further examination of the linkages between environment, socio-economic changes and disease trends. It was the Ottawa Charter of Health Promotions [20] that revitalized the interest in understanding social determinants and it recognized peace, shelter, education, food, income, a harmonious eco-system, resources, social justice and equity as essential pre-requisites for health. In spite of such a powerful international charter, the approach to social determinants remains extremely individualized and behavioral. Nonetheless, it was the introduction of a high profile Commission on Social Determinants that highlighted the social determinants in global public health policy. It was after its commencement that an extensive background and conceptual work have been accomplished [3].The Commission on Social Determinants of Health offered convincing evidence that health inequities are caused due to diversity in a variety of social and environmental factors and are not natural phenomena. The CSDH defines the Social Determinants of Health (SDH) as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system. It supports countries to offer Universal Health Coverage to tackle health inequity directly. Moreover, the report recognizes that health inequities arise not only from within but also from beyond the domain of health, through other social determinants, including the unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services, globally and nationally, the consequent unfairness in the immediate, visible circumstances of people’s lives - their access to healthcare, schools, and education, their conditions of work and leisure, their homes, communities, towns, or cities - and their chances of leading a flourishing life [21].

4. Results and Discussion

- The area of the social determinants of health is possibly the most multifaceted and challenging of all. It takes into consideration the important characteristics of people’s living and working conditions and their lifestyles. It also focuses on how the economic and social policies play an important role in improving health [22]. It is well known fact that the medical care can extend survival and improve diagnosis after some serious diseases, but what is most important is to understand the relationship between various social determinants and their impact on health outcomes in general and various components of maternal health in particular. The social factors become more significant for the maternal health as these factors directly have a bearing on the woman’s health as well as on the health of the fetus. We will explore, on the basis of available evidences, some of those factors which act as social determinants of maternal health.

4.1. Age

- Marriage of girls at an early age due to cultural factors like dowry related burden, religious factors, economic factor like poverty where parents cannot afford to continue to feed the female child and educate her higher, leads her to face the pregnancy related complications which culminate into complicated childbirth. Age becomes significant determinant when we consider the teenage pregnancies. Despite the Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1978, 34 percent of all women are married below the legal minimum age of marriage i.e. 18 years which is higher in rural areas than urban areas. Adolescent girls face considerable health risks during pregnancy and childbirth. Girls in the age group of 15 to 19 years are likely to die twice more than women in their twenties from childbirth. A study by Craft in 1997 showed that even older women face greater risk of complications from pregnancy and poor outcomes. For many of these women these risks are increased because of the number of pregnancies and deliveries which they initially have practiced. Not only do the women face complications but also the social stigma of producing more children even at later stages of life.

|

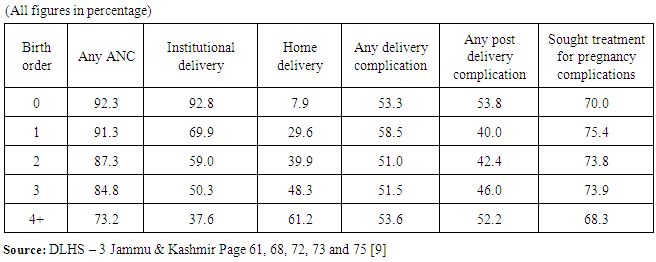

4.2. Birth Order

- The DLHS-3 data collected for the state of Jammu and Kashmir gives detailed information about the relationship between birth order and ANC services. As it is clear from Table 3, with the increasing number of living children from zero to four, there was a declining trend of receiving any ANC, 92.3 percent women with no child received ANC as against this only 73.2 percent women with four or more living children received any antenatal check-up.

|

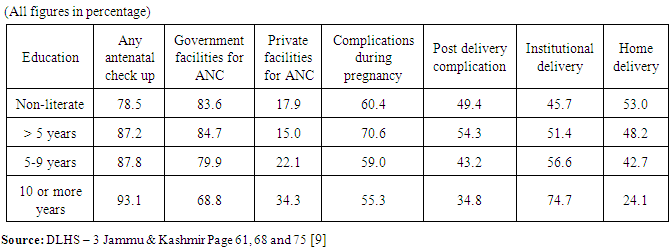

4.3. Education

- Using data from the World Health Organization’s Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health, researchers found that women with no education were nearly three times more likely to die during pregnancy and childbirth than women who had finished secondary school [23]. A mother’s education not only helps her survive, but also plays an influential role in her child’s survival past age five. Research shows that better educated mothers tend to have healthier children. Education is likely to enhance female autonomy so that women develop greater confidence and capabilities to make decisions regarding their own health, as well as that of their children [24]. It’s also likely that educated women seek out higher quality services and have a greater ability to use health care inputs to produce better health. This is consistent with research by Streat- field et al. (1990) [25], who found that more educated women are more likely to be aware of the benefits of health care and as a result, are more likely to use preventive health care services. Some studies suggest that although the JSY has increased institutional delivery significantly, the poorest and the least educated women receive the benefit to the minimum, and hence there is call for improving maternal care utilization among the poorest and least educated women [26].

|

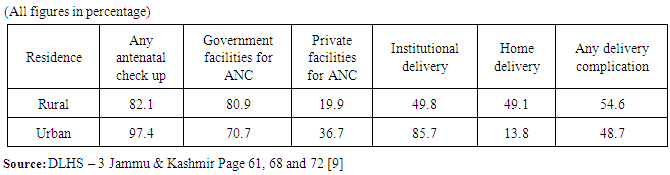

4.4. Residence

- Rural-urban differences are also found to be having a considerable influence on maternal health. Urban women are found to have a better accessibility to ante natal and post natal care. Besides, they also have a better awareness towards different health care necessary during the pregnancy and childbirth. Also the urban women are found to be going for institutional deliveries more than the rural women. Pebley et al. (1996) [27] found that distance to the nearest clinic was considerably and negatively related to both prenatal care and delivery assistance in Guatemala. There is sufficient evidence that financial barriers, shortages of trained personnel, especially in rural areas, and poor performance on the part of trained personnel all have a say to high levels of maternal mortality in developing countries [28].

|

4.5. Income

- The income of the family itself may affect maternal health outcomes. A family with low income may be constrained in being able to pay for health service fees, transport to facilities, or health-related resources that incur additional expense (e.g., nutritious food, contraceptive supplies or condoms, some biomedical tests). Income is an important determinant of maternal health as it helps provides the necessary resource to access and afford the essential care and treatment needed by the women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. The health of a woman is not only affected if she does not receive the required ante natal or post natal care during and after the pregnancy period but also if she has been left ignored during her child hood in terms of nutrition, education which are in turn affected by the low economic profile of the family where she is born. Besides low income, gender inequality also plays a considerable role which leaves girl child face disadvantage to male child. Further, a poor woman also faces a violation in her dignity from the health personnel during institutional deliveries.

|

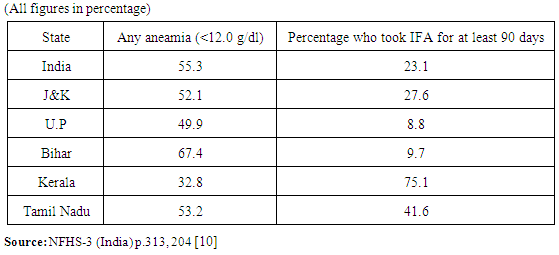

4.6. Nutritional Status

- Food again is very important factor that has an impact on woman’s health. A healthy mother can give birth to a healthy child. A woman who eats balanced diet does not suffer from severe anaemia. Further she also does not need to rely on iron supplements which although can reduce her iron deficiency but can lead to other problems. During pregnancy a women has increasing demands for energy both for her and the growing foetus. Therefore it is important that she gets proper nutritious food as well as good care in absence of which there can be complications or sickness in mother as well as the baby.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- The social determinants of health are the socio-cultural and politico- economic conditions – and their distribution among the population – that influence individual and group differences in health status. They are risk factors found in one's living and working conditions (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, and power), rather than individual factors (such as behavioral risk factors or genetics) that influence the risk for a disease, or vulnerability to disease or injury. These distributions of social determinants are largely shaped by public policies that reflect the influence of prevailing political ideologies of those governing a jurisdiction.Several factors that are associated with increased risk of maternal deaths are age at marriage/delivery, frequency of births, spacing between births, economic conditions, utilization of antenatal care, post partum care, institutional delivery services etc. and the evidences provided by the DLHS-3 and NFHS-3 data suggest that these factors are important determinant of maternal health in Jammu & Kashmir.

6. Recommendations

- As maternal health is intricately tied to women’s social and economic status, investments in girls’ and women’s education and empowerment are critical for preventing maternal deaths. Global efforts toward achieving Millennium Development Goals 2 and 3—to achieve universal primary education and promote gender equality and empower women, respectively—are thus vital for improving the health of girls, women, and their families worldwide. Maternal health must be recognized as a key development issue by the developing countries and must commend to increasing the quality and accessibility of reproductive health care. This can be done by addressing social and cultural factors that may discourage some of the most vulnerable women from seeking care. Also the woman must be educated about her health and about the importance of proper care to be taken during pregnancy and childbirth.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML