-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2015; 5(2): 50-57

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20150502.02

Prevalence, Awareness and Control of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in a Low-Income Population in Macao, China

Cheng-Kin Lao1, Yok-Man Chan1, Henry Hoi-Yee Tong1, Alexandre Chan2

1School of Health Sciences, Macao Polytechnic Institute, Macao S.A.R., China

2Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Correspondence to: Cheng-Kin Lao, School of Health Sciences, Macao Polytechnic Institute, Macao S.A.R., China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Previous literature showed that low-income people were more likely to develop cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension. However, these risk factors were often under-recognized and under-treated. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the prevalence and awareness of diabetes and hypertension in a low-income population in Macao. This cross-sectional study targeted the adult beneficiaries of the local food bank, which was established to provide food assistance to the residents who had low income but were ineligible for government financial assistance. Their health data such as blood glucose (BG) levels, blood pressure (BP), lifestyle characteristics and medical history were collected through on-site measurement and interview. Out of the 252 participants, 21.4% and 48.4% were screened positive for diabetes and hypertension, respectively. The awareness rate of diabetes was 72.2%, while 78.7% of participants with hypertension were aware of the condition. Among those who were treated, 48.6% and 57.3% achieved adequate glycemic and BP control, respectively. After adjusting for covariates, a lack of formal education (OR=4.10, 95%CI=1.47-11.47) was associated with poor BP control. In conclusion, diabetes and hypertension were prevalent and largely uncontrolled in the study population. Chronic disease self-management programs and other health education services can be potential strategies to improve their cardiovascular health.

Keywords: Awareness, Control, Diabetes, Hypertension, Low income, Macao, Obesity, Prevalence

Cite this paper: Cheng-Kin Lao, Yok-Man Chan, Henry Hoi-Yee Tong, Alexandre Chan, Prevalence, Awareness and Control of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in a Low-Income Population in Macao, China, Public Health Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 50-57. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of mortality worldwide, claiming 17.3 million lives yearly [1]. CVDs are also major contributors to global disease burden and are associated with substantial economic costs [1]. Although most cases of CVDs can be avoided by addressing the modifiable risk factors, it is projected that the number of CVD-related deaths will increase to 23.3 million per year by 2030 [2]. A potential reason for the upward trend is under-recognition of CVD risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. This issue is prevalent and requires special attention in many Asian countries. In China, for example, more than two-thirds of the patients with diabetes are not aware of their condition [3]. Similarly, a poor level of awareness has been observed among Chinese patients with hypertension [4].As a Special Administrative Region in China, Macao has emerged as one of the world’s fastest growing economies due to the expansion of gambling industry. In 2012, Macao ranked sixth in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in the world [5]. In parallel with the economic boom, income inequality has become a major concern in the society. A local report revealed an increasing trend in the proportion of workers earning less than half of the median income from 2003 to 2007 [6]. The government has implemented a series of subsidy schemes to help the poor. As the poverty threshold is not officially established in Macao, the government uses the minimum subsistence index (MSI) to determine people’s eligibility for financial assistance. The MSI is periodically adjusted based on multiple factors such as the cost of living. All residents whose monthly income is below the MSI (USD 420 for a single-person household as in July 2012) are eligible for various types of financial assistance [7, 8]. However, due to the persistently high inflation rate, a number of low-income residents who do not qualify for financial assistance are struggling to afford a basic standard of living [9].In Macao, the healthcare system consists of the public and private sectors. All permanent residents are entitled to free primary medical care at the public health centers or stations, and 30% of the fees for specialist medical services at the public hospital are subsidized by the government. In addition, all medical services and treatment are free of charge for several population subgroups such as those aged 65 years or older, public servants, pregnant women, children, school teachers, and patients with certain diseases [10, 11]. In general, the heavily subsidized public healthcare system is preferred by people with low income [9]. However, the public system has been under constant pressure to keep up with the growing demand, with only one public hospital and nine health centers or stations serving a population of approximately 614,500 [10, 12]. The long waiting time in the public sector may negatively affect the access to health care by economically disadvantaged residents. Currently, there is a lack of data on the health status of low-income residents in Macao, especially those who are excluded from the financial assistance network. Previous literature has shown a potential association between CVDs and low income [1]. As diabetes is one of the strong risk factors for CVDs, this study was designed to assess the prevalence and awareness of diabetes among a low-income population who was ineligible for financial assistance. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the prevalence and awareness of other CVD risk factors including hypertension and obesity. The data were also analyzed to identify the factors associated with the prevalence and poor control of diabetes and hypertension. This study serves as the first step for further investigations on how to improve cardiovascular health among the poor.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

- This was a cross-sectional study conducted between October 2012 and August 2013. A total of eleven free health screening events were held for the food bank beneficiaries. As the only one of its kind in Macao, the food bank program targets any residents who earn 1 to 1.7 times the MSI and do not qualify for government financial assistance. In addition, they must meet the strict requirements of cash and bank savings [13]. The majority of the beneficiaries are unemployed, homeless, or elders who live alone. After their eligibility is verified, the beneficiaries are allowed to receive food assistance weekly for up to eight weeks. If their financial situations are not improved at the end of this period, they can apply for renewal of this benefit [13]. All food bank beneficiaries aged 18 years or older were deemed eligible for this study. A convenience sampling approach was used and participants were recruited through posters and announcements on food distribution days. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants who attended the health screening events. Oral consent was taken from those who were illiterate and documented by witnesses. Participants with missing data were excluded from analysis. A sample size calculation was conducted and the required sample size was 132, based on the estimated prevalence of diabetes (9.49%) in the general population [14] and the total number (2,460) of food bank beneficiaries in 2012 [7]. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the Macao Polytechnic Institute (MPI).

2.2. Data Collection

- Under the investigators’ supervision, health screening was performed by an MPI volunteer team which comprised students of the nursing, pharmacy and medical laboratory programs. On-site measurement of body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP) and blood glucose (BG) levels was performed. All participates were requested in fasting condition prior to the measurement. BG levels were assessed by point-of-care testing (SD Code-FreeTM glucose meter; SD Biosensor, Korea). BP was measured in the sitting position using a digital sphygmomanometer (Microlife® BP3AQ1; Microlife AG, Switzerland) following at least five minutes of rest. Among the participants whose systolic blood pressure (SBP) was lower than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was lower than 90 mmHg [15], only one single measurement was obtained. Otherwise, a second reading was taken on the same arm at the end of screening, which was at least fifteen minutes from the first measurement, and the mean of the two readings was used for data analysis. Body weight was measured using a digital scale. To ensure their accuracy, all instruments were calibrated prior to the screening events. Health information was collected through face-to-face interview and a structured questionnaire adapted from the Macao Health Survey 2006 [16]. Data collection parameters included demographic variables (gender, marital status, education level, and employment status), self-reported medical history, and lifestyle characteristics. In order to minimize bias, extensive training was provided to all student volunteers. They were required to strictly follow the standardized procedures to administer the questionnaire and perform the measurement.

2.3. Definitions of Study Outcomes

- In the present study, diabetes was defined as a fasting BG level of at least 7.0 mmol/L, or current use of antidiabetic medications [17]. The definition of hypertension in this study was mean SBP of at least 140 mmHg, mean DBP of at least 90 mmHg, or current use of BP-lowering medications [4, 15]. BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height. The cut-off points of overweight and obesity were 23 kg/m2 and 25 kg/m2, respectively, as recommended for Asian adults [18].Among the participants defined as having diabetes, awareness was determined by a positive response to the question, “Have you ever been told by a physician or other health professionals that you have diabetes?” The same question format was used for assessing participants’ awareness of hypertension and obesity [4, 19]. Treatment of diabetes or hypertension was established by participants’ self-reported use of medications for the conditions. Adequate control of diabetes was defined as a fasting BG level of 7.2 mmol/L or lower, as recommended by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [17]. Hypertension was considered under control among those receiving treatment if their SBP was lower than 140 mmHg and their DBP was lower than 90 mmHg [4]. Self-rated health was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor). With respect to lifestyle characteristics, all participants were asked about their smoking status (never, past, or current smokers). Their self-reported exercise frequency over the past year was classified into three categories: regular exercise (at least three times weekly), occasional exercise (from once monthly to less than three times weekly), and a lack of exercise (less than once monthly) [16].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics were used to report the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of CVD risk factors and basic variables. Univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the unadjusted relationship between different variables and the predefined outcomes which included the prevalence and poor control of diabetes and hypertension. To identify the independent factors associated with these outcomes, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed on the variables that showed statistical significance in the univariate analysis, with a p-value of 0.05 as the cut-off point. All statistical analyses were completed by using SPSS for Windows, version 20.0.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Lifestyle Characteristics

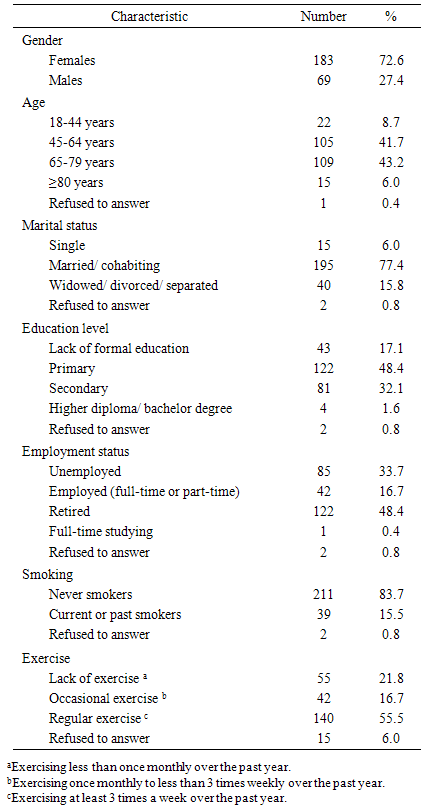

- A total of 291 adults took part in the health screening events during the study period. Thirty-nine participants were excluded because they did not complete the fasting BG measurement. As a result, 252 (86.6%) participants were eligible for analysis. Their mean age was 62.2±12.7 years, ranging from 19 to 93 years. Among them, 124 (49.2%) were 65 years or older and 183 (72.6%) were females. With respect to lifestyle-related risk factors for CVDs, 39 (15.5%) participants reported to be current or past smokers. Forty-two (16.7%) participants claimed to exercise once monthly to less than three times weekly, while 55 (21.8%) participants lacked exercise over the past year (Table 1).

|

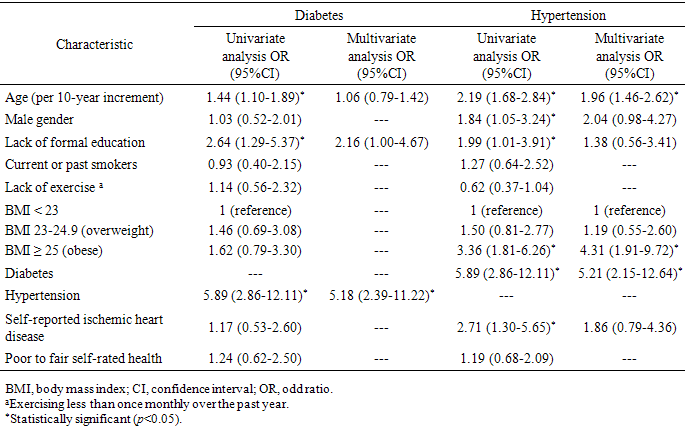

3.2. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment and Control of Diabetes

- Out of the 252 participants, 54 (21.4%) were screened positive for diabetes, with 72.2% of them being aware of the condition. Thirty-seven (68.5%) participants with diabetes received treatment, whereas only 48.6% of them achieved the ADA glycemic goals (Figure 1). According to the univariate analysis, older age, hypertension, and a lack of formal education significantly increased the likelihood of diabetes (all with p<0.05). Following adjustment for covariates, hypertension (OR=5.18, 95%CI=2.39-11.22) was identified as the independent factor related to diabetes (Table 2). However, none of the participant characteristics were found to be significantly associated with poor glycemic control.

| Figure 1. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of diabetes among the study participants |

|

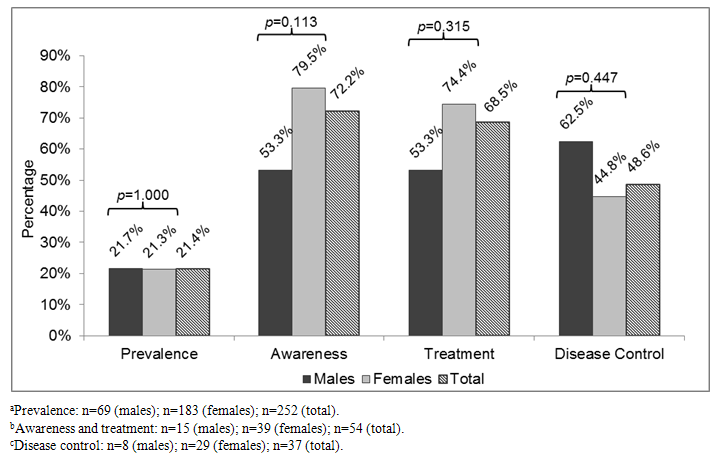

3.3. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment and Control of Hypertension

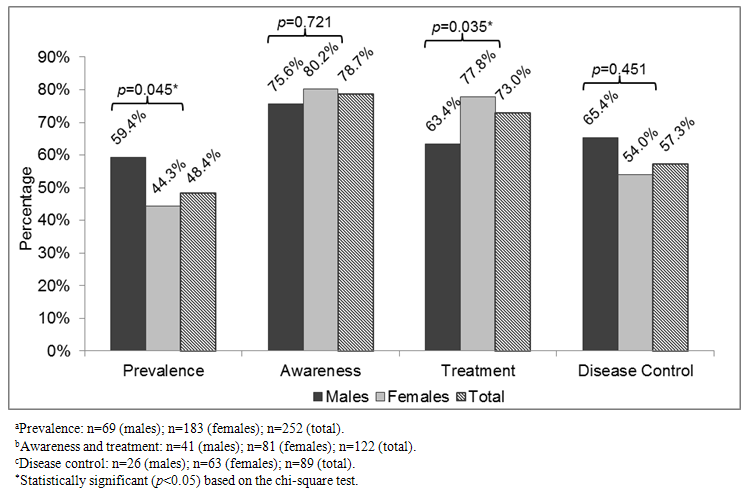

- Among the study participants, 122 (48.4%) were screened positive for hypertension. Among those with increased BP, 78.7% were aware of the condition and 73% were treated with one or more antihypertensive medications. Nevertheless, only 57.3% of those taking medications had their BP under control (Figure 2). The univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that hypertension was significantly related to older age, male gender, obesity, diabetes, self-reported ischemic heart disease, and a lack of formal education (all with p<0.05). After adjusting for covariates, older age (OR=1.96, 95%CI=1.46-2.62), obesity (OR=4.31, 95%CI=1.91-9.72), and diabetes (OR=5.21, 95%CI=2.15-12.64) were identified as the independent factors associated with hypertension (Table 2). The factors linked to poor BP control were also evaluated. It was found that the participants who lacked formal education were more likely to have uncontrolled BP (OR=4.10, 95%CI=1.47-11.47).

| Figure 2. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among the study participants |

3.4. Prevalence of Obesity and Other Self-Reported Health Problems

- Sixty-three (25%) participants were overweight and 70 (27.8%) were obese, as determined by their BMI. Among the obese participants, 20 (28.6%) were aware of their condition. Based on self-reporting, 41 (16.3%) participants were diagnosed with ischemic heart disease. Overall, 70.6% of participants rated their health status as “fair” or “poor.”

4. Discussion

- This is the first study that evaluates the prevalence of CVD risk factors among low-income residents in Macao. More than one-fifth of the participants were screened positive for diabetes and almost half of the participants met the definition of hypertension in this study. Furthermore, more than half of the participants were either overweight or obese. These alarming results indicate that the study population is highly susceptible to CVDs. Considering that poor people may have worse long-term CVD outcomes than their high-income counterparts [20], it is important to adequately address the modifiable CVD risk factors in this vulnerable group. According to the International Diabetes Federation, the prevalence of diabetes was estimated to be 9.49% in the general population in Macao [14]. A local study demonstrated that 34% of the general population had hypertension [11]. Although it may be inappropriate to perform a direct comparison owing to the demographic differences between these studies, the strikingly higher prevalence in this study population should warrant attention from policymakers and healthcare providers. In addition, the findings of the present study are in agreement with those of previous literature, which showed the association between low socioeconomic status and CVD risk factors. A Taiwanese study found that poor people were 50% more likely to develop diabetes than the middle-income group [21]. In Hong Kong, hypertension was three times more prevalent in people who had low household income when compared with those belonging to the highest income group [22]. Another reason for the high prevalence of both conditions was that people aged 65 years or older accounted for almost half of the study participants. The elderly who live alone are among the major beneficiaries of the food bank program and multiple studies have revealed that older age is a risk factor for diabetes and hypertension [3, 11, 22, 23]. In order to prevent CVDs and other complications, all patients with increased BP or BG levels should seek medical help and initiate treatment early. However, these two chronic conditions are highly under-recognized and under-treated among Chinese patients. While there is a lack of relevant data about diabetes in Macao, a nationwide study in China showed that only 30.1% of patients with diabetes were aware of the disease and 25.8% received treatment [3]. On the other hand, according to a population-based study in Macao, 67% of patients who had hypertension were aware of their condition and 59% were treated [11]. Contrary to the expectation, the rates of awareness and treatment of both chronic conditions exceeded 68% in the present study. It was possibly because two-thirds of the participants with increased BP or BG levels were 65 years or older. Compared with their younger counterparts, the elderly are more prone to multiple comorbidities [24] and use medical services more frequently [25]. It is not surprising that they are also more likely to recognize their health problems [4, 11]. Moreover, the elderly have better access to medical care in Macao because they are entitled to free consultation and medication treatment provided by the public healthcare system [10].In spite of the relatively high treatment rates, this study demonstrated that both CVD risk factors were far from adequately controlled. The results were in line with those of other studies in Hong Kong, in which the control rates of diabetes and hypertension were 39.7% and 52.5%, respectively [26, 27]. In this study, the low control rates of both conditions may be attributable to the participants’ education levels. A non-significant trend was observed towards poorer glycemic control in the participants who did not have formal education, while a robust association was found between a lack of formal education and poor BP control. Both poverty and low education levels appear to be linked to low health literacy [28]. People with low health literacy generally have poorer medication adherence and attitude towards the diseases, resulting in worse control of BP and BG levels [29, 30]. In Macao, although all permanent residents are covered by the public healthcare benefit scheme, the long waiting time in the public hospital and health centers may adversely affect the quality of disease management. Patients may not receive their follow-up care as frequently as they should. This issue can be overcome by using a multidisciplinary team approach, which has been shown to improve glycemic and BP control [31, 32]. While physicians take the initiative to optimize treatment plans, nurses and pharmacists should play a more active role in monitoring and educating patients on therapeutic goals, lifestyle modification, and appropriate use of medications. Social workers are also needed to offer support and ensure access to medical care for low-income patients. Another potential strategy is to enhance patients’ self-management skills. It has been reported that chronic disease self-management programs can reduce healthcare utilization and improve clinical outcomes in other countries [33]. There is a need to explore how to implement similar types of programs in Macao, and to evaluate their long-term benefits on cardiovascular health among low-income patients.It is also noteworthy that approximately 70% of obese participants failed to recognize their weight condition, with females as the majority. According to previous literature, females with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to underestimate their body weight [34]. Under-recognition of obesity can be dangerous because of its strong association with various chronic diseases. For instance, obese participants had a four-fold risk for hypertension in this study. More efforts are required to educate people on the accurate assessment of their weight status, the health risks of obesity, and appropriate weight-loss methods. In order to tackle the obesity problem, local policymakers should consider implementing free or affordable fitness programs for the low-income population. Several limitations should be noted in this study. First, the study targeted a subgroup of low-income population who earns more than the MSI and thus is not eligible for government financial support. As a consequence, the findings may not be generalizable to the “poorest” residents whose income is below the MSI. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that the study population is under considerable financial distress because of the high cost of living in Macao, and the rapid growth of this population is gaining much attention in the society [7, 35]. Moreover, selection bias cannot be ruled out due to the use of convenience sampling method. For example, the food bank beneficiaries who suffered from poorly controlled diseases might not be able to attend the screening events. In addition, the study was designed for the purpose of health screening rather than clinical diagnosis. According to the ADA guideline, the hemoglobin A1c test and the oral glucose tolerance test are recommended for diagnosis of diabetes [17]. However, neither test was performed owing to the screening nature of the study. For a similar reason, BMI was selected to classify obesity despite its failure to distinguish between lean and fat body mass. The surrogate markers of visceral adiposity such as waist circumference may be better predictors of CVD risks and should be added to assess obesity in future studies [36]. Due to time constraints at the health screening events, a single BP measurement was performed if the first reading was lower than 140/90 mmHg, although multiple BP readings may have greater predictive power than a single measurement [37]. To minimize the impact of this limitation, a second BP reading was obtained if the first reading was elevated, and the analysis was based on the mean of the two readings. After all, the first BP reading tends to be the highest when multiple readings are measured [37]. Furthermore, the results were subject to recall bias because some medical data were collected on a self-report basis. Ideally, the participants’ medical history should have been obtained from their medical records. Nevertheless, the community-based nature of the study made it impossible to perform a chart review.

5. Conclusions

- Diabetes and hypertension were prevalent and largely uncontrolled among the low-income residents who were excluded from the financial assistance network in Macao. The findings of this study imply that the provision of free or highly subsidized medical services alone may not be enough for improving health among the poor. A large-scale campaign should be implemented to educate low-income people about the risk factors and prevention of CVDs. All levels of health professionals should work together to optimize disease management and motivate patients to adhere to their medications. The government should expand the public healthcare system to reduce the waiting time and further enhance poor people’s access to medical care. The next stage of research will be expanded to include the other subgroups of low-income population such as the residents receiving government financial assistance. Additional studies are needed to measure the clinical outcomes of chronic disease self-management programs and other health education services for the low-income population in Macao.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study is financially supported by the Macao Polytechnic Institute (project code: RP/ESS-02/2012). The authors gratefully acknowledge Ms. Pui-Kei Wong, Ms. Lai-San Mok, and the other staff of Caritas Macao for their assistance in organizing the health screening events. We also wish to thank Ms. Sok-Wa Leong, Ms. Wai-Fun Wong, Ms. Qian-Min Zheng, and Mr. Kam-Ho Siu of the Macao Polytechnic Institute for their contribution to volunteer recruitment, training, and management of equipment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML