-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2015; 5(2): 39-49

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20150502.01

Physical Activity Change of English, French and Chinese Speaking Immigrants in Ottawa and Gatineau, Canada

Ning Tang1, Colin MacDougall1, Danijela Gasevic2

1Discipline of Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

2Centre for Population Health Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9YL, UK

Correspondence to: Ning Tang, Discipline of Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

OBJECTIVES: The multicultural study aims at examining Physical Activity Change of English, French and Chinese speaking immigrants in Ottawa and Gatineau, Canada, and identifying demographic factors that correlate with the change and impact the change. METHODS: 810 immigrants of three language sub-groups were recruited by purposive-sampling. Using self-reports, respondents answered questions regarding Physical Activity Change and Demography in Multicultural Lifestyle Change Questionnaire of English, French or Chinese version. Data were analyzed statistically in percentage, correlation, regression and factor analysis. RESULTS: Immigrants of different gender, language and category sub-groups exhibited different rates in Physical Activity Change, and different language sub-groups displayed different Physical Exercise Items rates after immigration, but no statistical difference between the rates. Physical Activity Change (Physical Activity Behavior Change + Physical Activity Belief Change) was negatively correlated with Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status and Primary Occupation. Physical Activity Behavior Change was negatively correlated with Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status and Primary Occupation. Age, Gender, Category of Immigration and Employment Status significantly impacted Physical Activity Change. Mother Tongue, Age, Gender, Category of Immigration and Employment Status significantly impacted Physical Activity Behavior Change. Two factors (factor one: physical activity behavior change factor and factor two: physical activity belief change factor) influenced significantly Physical Activity Change. Factor one exposed more significant effect than factor two. CONCLUSIONS: Different immigrant sub-groups experienced different Physical Activity Change and three language sub-groups presented different physical activity patterns after immigration. Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status and Primary Occupation were main factors impacting significantly Physical Activity Change. Mother Tongue was an important factor influencing significantly Physical Activity Behavior Change. Culture and acculturation were relating contributing factors. Data may provide evidence and implication for physical exercising policy-making and policy-revising in Canada.

Keywords: Immigration, Culture, Acculturation, Physical Activity Change, Difference, Correlation, Impacting Factors

Cite this paper: Ning Tang, Colin MacDougall, Danijela Gasevic, Physical Activity Change of English, French and Chinese Speaking Immigrants in Ottawa and Gatineau, Canada, Public Health Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 39-49. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20150502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Generally, the largest change in post-immigration lifestyle was related to physical activity levels. Most immigrants usually reported changes in physical activity since leaving their home countries, and exhibited less physical activity after immigration [1]. For instance, Canadian immigrants displayed lower participation in vigorous physical activity [2, 3], and they were less active during leisure time [4]. Indeed, Canadian non-European or non-Western immigrants, they were mainly Asian immigrants, but some of them were African immigrants, were somewhat more likely to have become physically inactive during their leisure time than European or Western immigrants in Canada [4, 5].English speaking immigrants represent one of the largest ethnic or cultural immigrant sub-groups in Canada and are the largest immigrant sub-groups in the Ottawa (Ontario) – Gatineau (Québec) region [6, 7], while French speaking immigrants are one of principal ethnic immigrant sub-groups in Québec and the second largest immigrant sub-group in the region [6, 7, 8]. It is interesting to note that Chinese speaking Canadians have constituted the largest ethnic immigrant sub-group entering Canada, one of the fastest-growing sub-groups in Canada since 1987 and the fourth largest sub-group following Arabic speaking immigrants in the Ottawa – Gatineau region [7, 9, 10].The main objectives of this study were to explore the differences in Physical Activity Behavior Change and Physical Activity Belief Change among different sub-groups of immigrants as well as to explore the covariates associated with the changes. The explorations show far-reaching significance in multicultural health research, health care, health policy-making and health promoting program in Canada.

2. Methods

- English, French and Chinese speaking immigrants at Adult Educational Centres/Schools, Christian Community Churches and Residential Communities in Gatineau and Ottawa, Canada were identified as the target population of this multicultural physical activity change study. Random sampling was impracticable for the study and could be biased because immigrant status of the three language sub-groups could not be identified effectively according to the sampling criteria. Purposive-sampling method was applied in the study to recruit qualified immigrant participants [11]. Participants must have been 18 years or older, have resided in Ottawa or Gatineau one year or more, and had been 16 years or older when they arrived in Canada. In total, 810 qualified participants were recruited to the study. Participants answered questions relating to Physical Activity Change and Demography in Multicultural Lifestyle Change Questionnaire of English, French or Chinese version, with all responses self-reported. The Multicultural Lifestyle Change Questionnaire was demonstrated by a pilot-test in the three immigrant sub-groups to have high validity (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.435 ˃ satisfactory value 0.40) [12, 13], and reliability (alpha coefficient α = 0.754 ˃ satisfactory value 0.70) before the multicultural study [14, 15].Physical Activity Change included Physical Activity Behavior Change and Physical Activity Belief Change. Physical Activity Behavior Change (dependent variable) was identified based on Physical Exercise Time Change, Physical Activity Level Change and Physical Exercise Item Number Change. Firstly, Physical Exercise Time Change was identified according to the response choices for two questions – “Before arrival in Canada, on average, how much physical exercise did you do each week?” (question one) and “Since arrival in Canada, on average, how much physical exercise do you do each week?” (question two). The response options for both of the two questions were as follows: “A. An hour or less”, “B. 2 – 3 hours”, “C. 4 – 5 hours”, “D. 6 – 7 hours”, “E. 8 hours or more” and “F. Do not know”. The respondent was identified experiencing Physical Exercise Time Change if there were different choices in the options of two questions except option “F” (i.e. picking option “A” for question one and choosing option “B” for question two). Meanwhile, the respondent was identified experiencing Physical Exercise Time Increase if choosing option “A” for question one and option “B” or “C” for question two. On the contrary, the respondent was identified experiencing Physical Exercise Time Decrease if choosing option “C” for question one and option “B” or “A” for question two. Secondly, Physical Activity Level Change was identified according to the response choices for two questions – “Before arrival in Canada, which of these descriptions best represents your physical activity level of a day?” (question one and “Since arrival in Canada, which of these descriptions best represents your physical activity level of a day?” (question two). The response options for both of the two questions were as follows: “A. Very light”, “B. Light”, “C. Moderate”, “D. Moderate heavy”, “E. Heavy” and “F. Do not know”. The respondent was identified experiencing Physical Activity Level Change if there were different choices in the options of two questions except option “F” (i.e. picking option “A” for question one and choosing option “B” for question two). Meanwhile, the respondent was identified experiencing Physical Activity Level Increase if choosing option “A” for question one and option “B” or “C” for question two. On the contrary, the respondent was identified experiencing Physical Activity Level Decrease if choosing option “C” for question one and option “B” or “A” for question two. Thirdly, Physical Exercise Item Number Change was identified according to the response choices for two questions – “Before arrival in Canada, which physical exercises did you take part in each week?” (question one) and “Since arrival in Canada, which physical exercises do you take part in each week?” (question two). The response options - eighteen Physical Exercise Items (A. Walking, B. Jogging/Running, C. Biking, D. Hiking, E. Skiing, F. Skating, G. Soccer, H. Basketball, I. Hockey, J. Tennis, K. Table tennis, L. Badminton, M. Swimming, N. Yoga, O. Chinese TaiJiQuan/QiGong, P. Fitness exercises, Q. Other, R. No exercise) were presented after the two questions for the multiple-choice. The respondent was identified experiencing Physical Exercise Item Number Change if there were the choices of different exercise items in the options of two questions. Meanwhile, the respondent was identified experiencing Physical Exercise Item Number Increase if there were more exercise items chosen in the options of question two than in the options of question one. On the contrary, the respondent was identified experiencing Physical Exercise Item Number Decrease if there were less exercise items chosen in the options of question two than in the options of question one.Fourthly, Physical Activity Belief Change (dependent variable) was identified according to the response choices for two physical activity belief questions – “Before arrival in Canada, which of these statements best describes your belief with regards to physical exercise?” (question one) and “Since arrival in Canada, which of these statements best describes your belief with regards to physical exercise?” (question two). The response options for both of the two questions were as follows: “A. The above mentioned exercises can very strongly promote health”, “B. The above mentioned exercises can strongly promote health”, “C. The above mentioned exercises can promote health”, “D. The above mentioned exercises can somewhat promote health”, “E. The above mentioned exercises can less than somewhat promote health”, “F. The above mentioned exercises cannot promote health” and “G. Do not know”. The respondent was identified experiencing Physical Activity Belief Change if there were different choices in the options of two questions except option “H” (i.e. picking option “A” for question one and choosing option “B” for question two). Immigrant status of English or French or Chinese speaking subjects was identified by the response for “Original Country” question – “What is your country of origin?”.Demographic characteristics (independent variable) of the study population were identified according to the response choices for the demographic questions relating to “Mother Tongue”, “Speaking Language”, “Age”, “Gender”, “Marital Status”, “Category of Immigration”, “Duration of Residence”, “Education”, “Employed Status”, “Employed Status”, “Primary Occupation”, “Religion” and “Income”. Data in Physical Activity Change and Demography were analyzed statistically for the different immigrant sub-groups.

3. Statistics

- Percentages in Physical Activity Change were calculated respectively, which included Physical Exercise Time Change Rate, Physical Exercise Time Increasing Rate, Physical Exercise Time Decreasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Change Rate, Physical Activity Level Increasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Decreasing Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Change Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Increasing Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Decreasing Rate, Physical Exercise Belief Change Rate in the Total Sample. Rates were also computed for different sub-groups including gender (immigrant men and women), language (English, French and Chinese speaking immigrant) and category (principal applicant immigrant, spouse and dependant immigrant, family class immigrant, other / refugee immigrant). Chi-square tests were performed to test if there were significant differences between rates of the sub-groups in Physical Activity Change. Following the descriptive analysis, correlation analysis was performed to test whether there were a correlation between the independent variables - Mother Tongue, Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status, Primary Occupation, and the dependent variables - Physical Activity Change (Physical Activity Behavior Change + Physical Activity Belief Change) and Physical Activity Behavior Change. Then, multiple linear regression analysis was used to determine if the independent variables had significantly impacted the dependent variables.Finally, factor analysis of two independent variables (Mother Tongue and Category of Immigration) and four dependent variables (Physical Exercise Time Change, Physical Activity Level Change, Physical Exercise Items Change and Physical Exercise Belief Change) was executed respectively to assess how many factors impacted significantly Physical Activity Change.

4. Ethical Approval

- The immigrant physical activity change study was part of a multicultural lifestyle change research project that was approved by Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, Flinders University in Australia in 2010 and by Office of Research Ethics and Integrity, University of Ottawa in Canada in 2014.

5. Results

5.1. Rates in Physical Activity Change

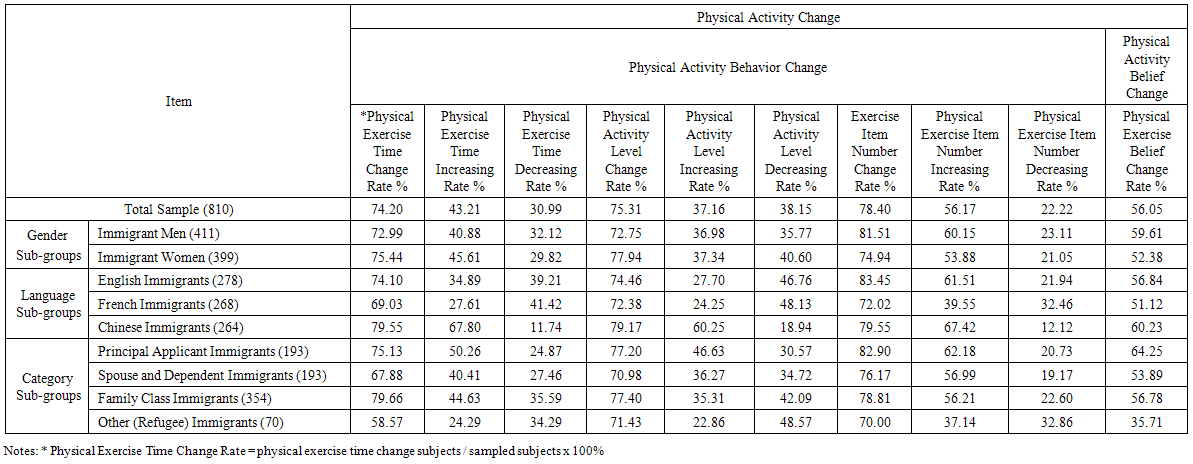

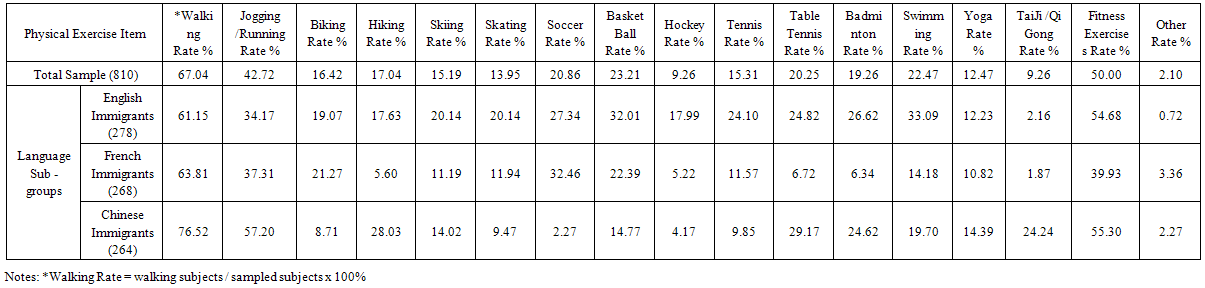

- Table 1 presents rates for total sample and different sub-groups in Physical Activity Change. Table 2 presents rates of total sample and language sub-groups in Physical Exercise Items after Immigration.

| Table 1. Rates for Total Sample and Different Immigrant Sub-groups in Physical Activity Change |

| Table 2. Rates for Total Sample and Language Sub-groups in Physical Exercise Items after Immigration |

5.2. Significance Level

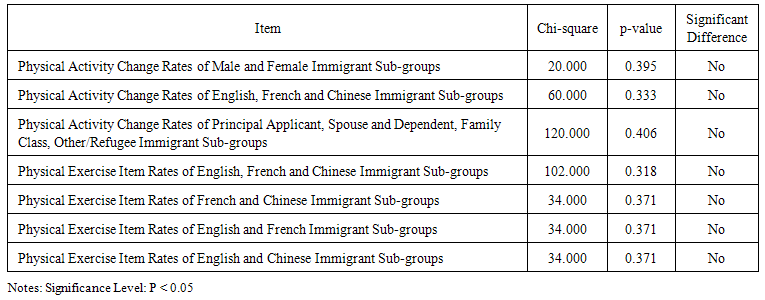

- Table 3 presents significance levels between Physical Activity Change Rates of different sub-groups.

| Table 3. Significance Level between Physical Activity Change Rates |

5.3. Multivariate Analysis

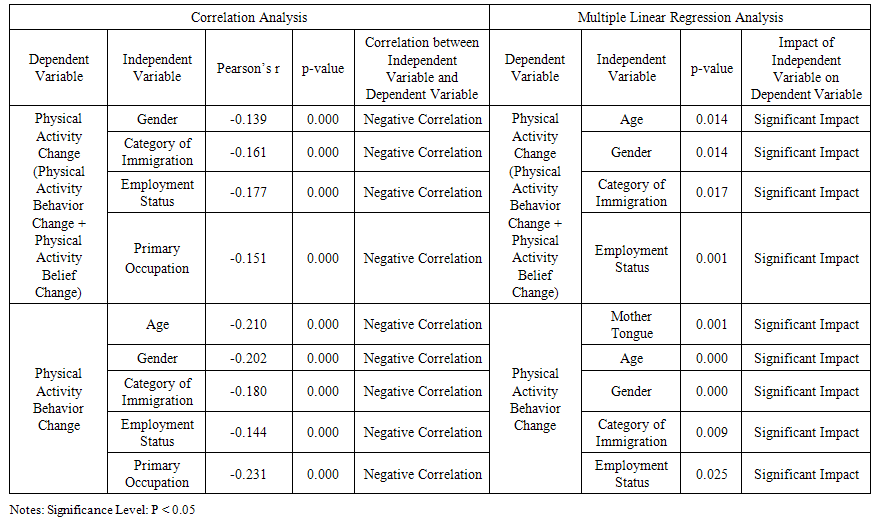

- Table 4 presents multivariate analysis results in Physical Activity Change.

| Table 4. Multivariate Analysis in Physical Activity Change |

5.4. Factor Analysis

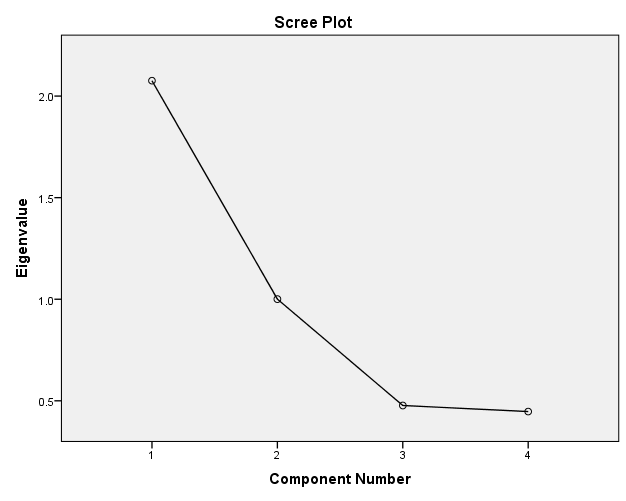

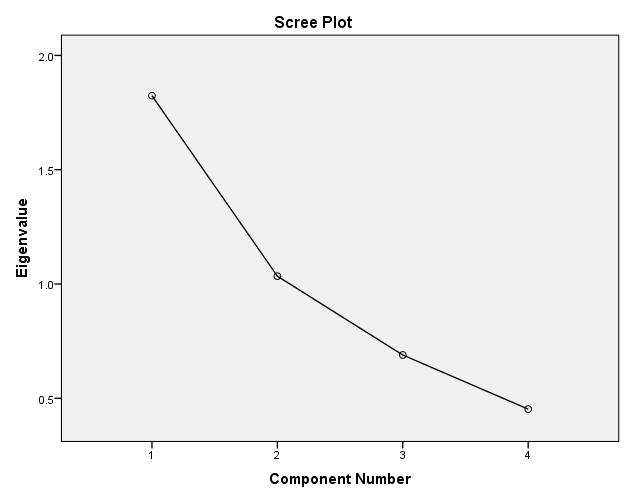

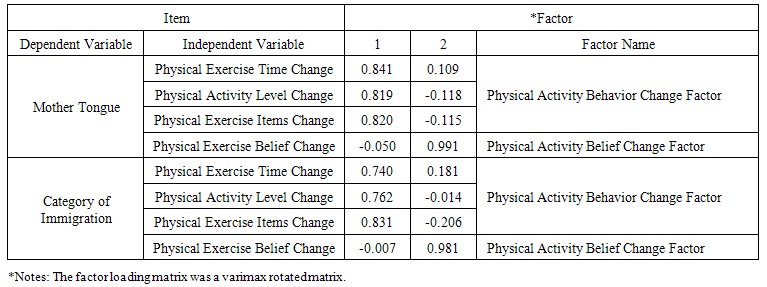

- Figure 1 and Figure 2 present scree plots of factor analysis.

| Figure 1. Factor Analysis for Mother Tongue to Physical Activity Change |

| Figure 2. Factor Analysis for Category of Immigration to Physical Activity Change |

| Table 5. Factor Analysis of Variables in Physical Activity Change |

6. Discussion

6.1. Percentages in Physical Activity Change

6.1.1. Total Sample

- The results of rates in Physical Activity Change show that the majority of immigrants changed physical exercise time, physical activity level and physical exercise item number. Most of immigrants increased their exercise time and item number. However, their physical activity level decreased slightly. Over 50% of the immigrants changed physical exercise belief. An immigrant and refugee study in US reveals that immigrants and refugees to the United States exhibited relatively low levels of physical activity [16]. A Health Report of Statistics Canada in 2013 shows that immigrants were less likely to be at least moderately active in their leisure time than Canadian citizens [17]. However, a Canadian HBSC Study in 2010 discloses that immigrant youth physical activity increased with increased time [18]. The results of Physical Activity Change of the immigrants in Ottawa and Gatineau supports the theory of physical activity acculturation. That is, as immigrants lived longer in a country, their physical activity behaviors and physical exercise belief were more closely approximate those of the host country. Acculturation has been broadly described as “the process by which immigrants adopt the attitudes, values, customs, beliefs, and behaviors of a new culture” [19, 20]. Acculturation is an indication of the cultural change of minority individuals to the majority culture [21]. Culture and acculturation are associated with leisure time physical activity [22]. For example, some of studies of Latin immigrants in the US show that higher acculturation was associated with a greater likelihood of recent exercise, and acculturation seems to be positively associated with participation in leisure-time physical activity [20, 23, 24, 25], and immigrants with low acculturation reported lower leisure-time activity than those who were highly acculturated [26]. Similarly, a study of Asian-Pacific immigrants displays that physical activity increased significantly more in intervention group of acculturation [27]. However, other research findings of Latin immigrants in the US exhibit that acculturation did not significantly influence exercise and decreases in physical activity were due to environmental and social barriers [21, 28]. Analogously, a study in the Netherlands shows that acculturation did not necessarily lead to increased physical activity during leisure time among Turkish young immigrants [5]. Moreover, some of findings reveal that acculturation to the US was significantly associated with a lower frequency of physical activity, and was a risk factor for obesity-related behaviors among Asian-American and Hispanic immigrants [29, 30].

6.1.2. Gender (Immigrant Men and Women) Sub-groups

- The results exhibit that different gender sub-groups had approximate rates in Physical Activity Change, which was similar to evidence of Canadian Community Health Survey which immigrant men and women had similar patterns of Physical Activity [31]. However, Physical Exercise Time Decreasing Rate, Exercise Item Number Change Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Increasing Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Decreasing Rate and Physical Exercise Belief Change Rate of male immigrants were higher than those of female immigrants. On the contrary, Physical Exercise Time Change Rate, Physical Exercise Time Increasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Change Rate, Physical Activity Level Increasing Rate and Physical Activity Level Decreasing Rate of female immigrants were higher than those of male immigrants. Female immigrants had greater Physical Exercise Time Change, increase of Physical Exercise Time, Physical Activity Level Change and decrease of Physical Activity Level than male immigrants. Nevertheless, male immigrants had greater Physical Exercise Item Number Change, increase of Physical Exercise Item Number than female immigrants, which appears that male immigrants accepted new culture and belief more easily than female immigrants. The Health Fact Sheets in 2013 discloses that Canadian males were more likely than females to be at least moderately active [32].

6.1.3. Language (English, French and Chinese Immigrant) Sub-groups

- The results disclose that different language sub-groups had different rates in Physical Activity Change. English Immigrants had the highest Exercise Item Number Change Rate, while French Immigrants exhibited the highest Physical Exercise Time Decreasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Decreasing Rate, and the lowermost Physical Exercise Time Change Rate, Physical Exercise Time Increasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Change Rate, Physical Activity Level Increasing Rate, Exercise Item Number Change Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Increasing Rate. However, Chinese Immigrants had the highest Physical Exercise Time Change Rate, Physical Exercise Time Increasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Change Rate, Physical Activity Level Increasing Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Increasing Rate, Physical Exercise Belief Change Rate, and the lowermost Physical Exercise Time Decreasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Decreasing Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Decreasing Rate. It is known that Chinese immigrants showed the longest Physical Exercise Time and the highest Physical Activity Level, while French immigrants exposed the shortest Physical Exercise Time and the lowermost Physical Activity Level. English immigrants had the greatest Physical Exercise Item Number Change, while Chinese immigrants had the most increase and the least decrease of Physical Exercise Item Number. However, French immigrants had the least increase and the most decrease of Physical Exercise Item Number. The Canadian HBSC Study in 2010 reveals that immigrant youth physical activity differed by ethnicity, and East and South East Asian youth have reduced physical activity levels [18].Meanwhile, the results display that Chinese immigrants had the greatest Physical Activity Belief Change, which seems to be due to huge cultural and traditional difference between original country and host country. On the contrary, French immigrants had the least Physical Activity Belief Change, which appears that they maintained their tradition and belief. A study in Vancouver, Canada reveals that physical activity of Chinese immigrants was influenced by culturally specific beliefs concerning appropriateness of physical activity for elders and importance of maintaining harmonious familial relationships [33]. Similarly, other study in Vancouver, Canada discloses that Chinese immigrant women were interested in learning more about “Canadian activities” to improve fitness, decrease stress and social isolation, and to be good role models for their children [34]. It is worth noting that language acculturation was positively associated with leisure-time activity and occupational activity [23, 35]. For instance, Latin women in the US with higher English language acculturation were more likely to be physically active than immigrants with lower English language acculturation [35]. For other instance, Spanish-speaking American immigrants had a higher prevalence of physical inactivity during leisure time than those who spoke mostly English and Latin immigrants with low language acculturation were less likely to engage in physical activity than those with moderate to high acculturation [23, 36]. Meanwhile, language preference and English language proficiency may exhibit different impacting effects of physical activity on different linguistic or ethnic immigrant sub-groups. For example, physical activity was significantly lower among Spanish-speaking Hispanics than among English-speaking Hispanics [37].

6.1.4. Category (Principal Applicant Immigrant, Spouse and Dependent Immigrant, Family Class Immigrant and Other/Refugee Immigrant) Sub-groups

- The results reveal that different category sub-groups had different rates in Physical Activity Change. It is observed that Principal Applicant Immigrants had the highest Physical Exercise Time Increasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Increasing Rate, Exercise Item Number Change Rate and Physical Exercise Belief Change Rate, and the lowermost Physical Exercise Time Decreasing Rate and Physical Activity Level Decreasing Rate, while Spouse and Dependent Immigrants had the lowermost Physical Activity Level Change Rate and Physical Exercise Item Number Decreasing Rate. However, Family Class Immigrants had the highest Physical Exercise Time Change Rate, Physical Exercise Time Decreasing Rate and Physical Activity Level Change Rate. It is noted that Other (Refugee) Immigrants had the highest Physical Activity Level Decreasing Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Decreasing Rate, and the lowermost Physical Exercise Time Change Rate, Physical Exercise Time Increasing Rate, Physical Activity Level Increasing Rate, Exercise Item Number Change Rate, Physical Exercise Item Number Increasing Rate and Physical Exercise Belief Change Rate. It is apparent that Family Class Immigrants had the greatest Physical Exercise Time Change, Physical Activity Level Change and decrease of Physical Exercise Time, while Principal Applicant Immigrants had the greatest increase of Physical Exercise Time and Physical Activity Level, the greatest Physical Exercise Item Number Change and the greatest increase of Physical Exercise Item Number. Yet, Other (Refugee) Immigrants had the least increase of Physical Exercise Time and Physical Activity Level, the greatest decrease of Physical Activity Level, the least increase and the greatest decrease of Physical Exercise Item Number. On the other hand, Principal Applicant Immigrants had the greatest Physical Activity Belief Change, which seems that they accepted new culture and tradition and changed their belief more easily, while Other (Refugee) Immigrants usually maintained their own custom and belief.

6.2. Physical Exercise Item Rates after Immigration

6.2.1. Total Sample

- The results exhibits that main Physical Exercise Item of the Canadian immigrants after immigration was Walking, followed by Fitness Exercises, which was the same as Canadian citizens, because Canadians' most popular leisure-time physical activity was walking, followed by home exercises and weight training [17]. It has been known that 71.1% of Canadians reported Walking during leisure time [32], which was higher than Walking rate (67.04%) of the immigrants in Ottawa and Gatineau. However, 34.4% of Canadians reported Home Exercises during leisure time [30], which was lower than Fitness Exercises (50.00%) of the immigrants in the two cities. It is worth to be mentioned that Health Reports of Statistics Canada disclose which immigrants were less likely to be physically active in their usual daily activities, but some of them spent at least six hours a week walking or bicycling as a means of transportation [17]. Similarly, a Community Health Survey in Canada reveals that recent immigrants were more likely to have lower likelihood of walking, sports, endurance, and recreation activities [38]. Though Swimming and Biking rates of Canadians were higher than those of the immigrants in Ottawa and Gatineau [29], but Jogging, Basket Ball, Soccer, Skating, Hockey and Tennis rates of Canadian citizens were lower than those of the immigrants [31]. It seems that preferring Physical Exercise Items of immigrants were different with those of Canadians. The results of Physical Exercise Item Rates after Immigration did not support strongly “immigrants were less likely to be physically active”. It is worth noting that the Canadian Community Health Survey data in 2000-2005 reveal that immigrants tended to participate in conventional forms of exercise compared to non-immigrants and were less likely to engage in endurance exercise, recreation activities, and sports [38]. It appears that some of physical exercise items were associated with acculturation. For instance, a study in US discloses that Walking of Latin immigrants during most of the day decreased from 82.8% to 65.6% as acculturation increased [29].

6.2.2. Language (English, French and Chinese Immigrant) Sub-groups

- The results show that English Immigrants had the highest Skiing, Skating, Basket Ball, Hockey, Tennis, Badminton and Swimming rates, and the lowermost Walking, Jogging/Running and Other rates. However, French Immigrants had the highest Biking, Soccer and Other rates, and the lowermost Hiking, Skiing, Table Tennis, Badminton, Swimming, Yoga, TaiJi/QiGon and Fitness Exercises rates. It is interesting to note that Chinese Immigrants had the highest Walking, Jogging/Running, Hiking, Table Tennis, Yoga, TaiJi/QiGon and Fitness Exercises rates, and the lowermost Biking, Skating, Soccer, Basket Ball, Hockey and Tennis rates. A physical exercise study in Ontario, Canada shows that 89% of Chinese immigrants reported Walking [39]. It is known that main Physical Exercise Items of English immigrants were Walking, Fitness Exercises, Jogging / Running, Swimming, Basket Ball and Soccer, while main Items of French immigrants were Walking, Fitness Exercises, Jogging/Running, Soccer, Basket Ball and Biking, but main items of Chinese immigrants were Walking, Jogging/Running, Fitness Exercises, Table Tennis, Hiking and Badminton. Therefore, different language sub-groups exhibited different rates in each Physical Exercise Item and different main Physical Exercise Item, which may be due to difference of their culture and physical activity acculturation.

6.3. Significance Level

- Though significance analysis shows that there was no significant difference between the rates of different immigrant sub-groups in Physical Activity Change, percent comparisons indicate substantial differences in some of the rates.

6.4. Multivariate Analysis

- The results of correlation analysis show that Physical Activity Change (Physical Activity Behavior Change + Physical Activity Belief Change) was negatively correlated with Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status and Primary Occupation, and Physical Activity Behavior Change was negatively correlated with Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status, and Primary Occupation. It is manifest that Age was not determinant of Physical Activity Belief Change. Further, the results of multiple linear regression analysis indicate that Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status significantly impacted Physical Activity Change, and Mother Tongue, Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status significant impacted Physical Activity Behavior Change. Therefore, Mother Tongue significant impacted Physical Activity Behavior instead of Physical Activity Belief.

6.5. Factor Analysis

- The results of factor analysis of two times show the same results that Physical Activity Change contained two factors. Factor one (Physical Activity Behavior Change Factor) consisted of three variables - Physical Exercise Time Change, Physical Activity Level Change and Physical Exercise Items Change. Factor two (Physical Exercise Belief Change Factor) consisted of one variable - Physical Exercise Belief Change. Two factors impacted significantly Physical Activity Change, but factor one had more significant effect on Physical Activity Change than factor two. Physical Activity Behavior Change contribute more strongly Physical Activity Change than Physical Exercise Belief Change.

6.6. Policy Implications

- Believably, the results of this physical activity change study can provide evidence for making and/or revising policies related to immigrant physical activity in Canada, which may regulate or adjust health care and services for immigrants, make more effectively health promotion programs in physical activity, lessen risk of chronic diseases, and reduce health inequality and inequity for immigrants. The data may help Health Canada policy makers to source and consider evidence of physical activity change for the vulnerable and marginalized population in decision-making and policy-modifying process, and to adapt appropriately evidence, prior to and during formulating new health policy or revising previous health policy. These will help Canadian immigrants improve their physical activity and health, and experience healthier status in order to contribute to Canadian economic and social development.

7. Conclusions

- The significant findings of this multicultural physical activity change study reveal that immigrants with different linguistic, cultural and social background in Canada experienced different physical activity changes, and English, French and Chinese immigrants exhibited different physical activity patterns after immigration. Different demographic factors significantly impacted immigrant physical activity change, such as Age, Gender, Category of Immigration, Employment Status significantly influenced Physical Activity Change, while Mother Tongue significantly affected Physical Activity Behavior Change. Meanwhile, original culture and physical activity acculturation of immigrants were relating contributing factors on Physical Activity Change. Future multicultural physical activity research should involve in exploring difference of physical activity change and physical activity patterns of immigrant ethnic or cultural sub-groups, and comparing difference of physical activity of immigrants and host residents for effective physical activity intervention and promotion programs. Data may provide evidence and implication for physical exercising policy-making and policy-revising in Canada.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors appreciate linguistic support of the bilingual teachers, Claude Couture and Denis Mascotto in Centre de formation professionnelle Vision-Avenir, Commission scolaire des Portages-de-l’Outaouais, Gatineau, Québec, Canada. Particularly, the authors are very grateful to research assistance of immigrant health expert, Dr. Brian Gushulak in Immigration Health Consultants in Canada.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML